2010 Special Volume 1:75–88

Archaeologies of the Early Modern North Atlantic

Journal of the North Atlantic

The Tensions of Modernity: Skálholt during the 17th and 18th Centuries

Gavin Lucas*

Abstract - Between 2002 and 2007, large-scale excavations at the episcopal manor and school of Skálholt in the southwest

of Iceland unearthed a massive assemblage of material culture dating from the mid-17th to late 18th century. One of the

key questions this paper will address is the position this settlement had within the wider religious, cultural, and economic

changes that were taking place over this time period, both within Iceland and the North Atlantic. Special emphasis will

be placed on understanding how ideology and the economic nexus were intertwined, and the contradictions that may have

emerged over time between these different elements. Skálholt led the Reformation in Iceland, but it was also in the vanguard

of the consumer revolution, being one of the most populous settlements in the country before the foundation of Reykjavik

as a town in the late 18th century. This paper explores what an archaeology of modernity might look like for Iceland, and in

particular, focuses on the relation between spatial organization and ideologies of community which were undergoing major

change at this time.

*University of Iceland, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland; gavin@hi.is.

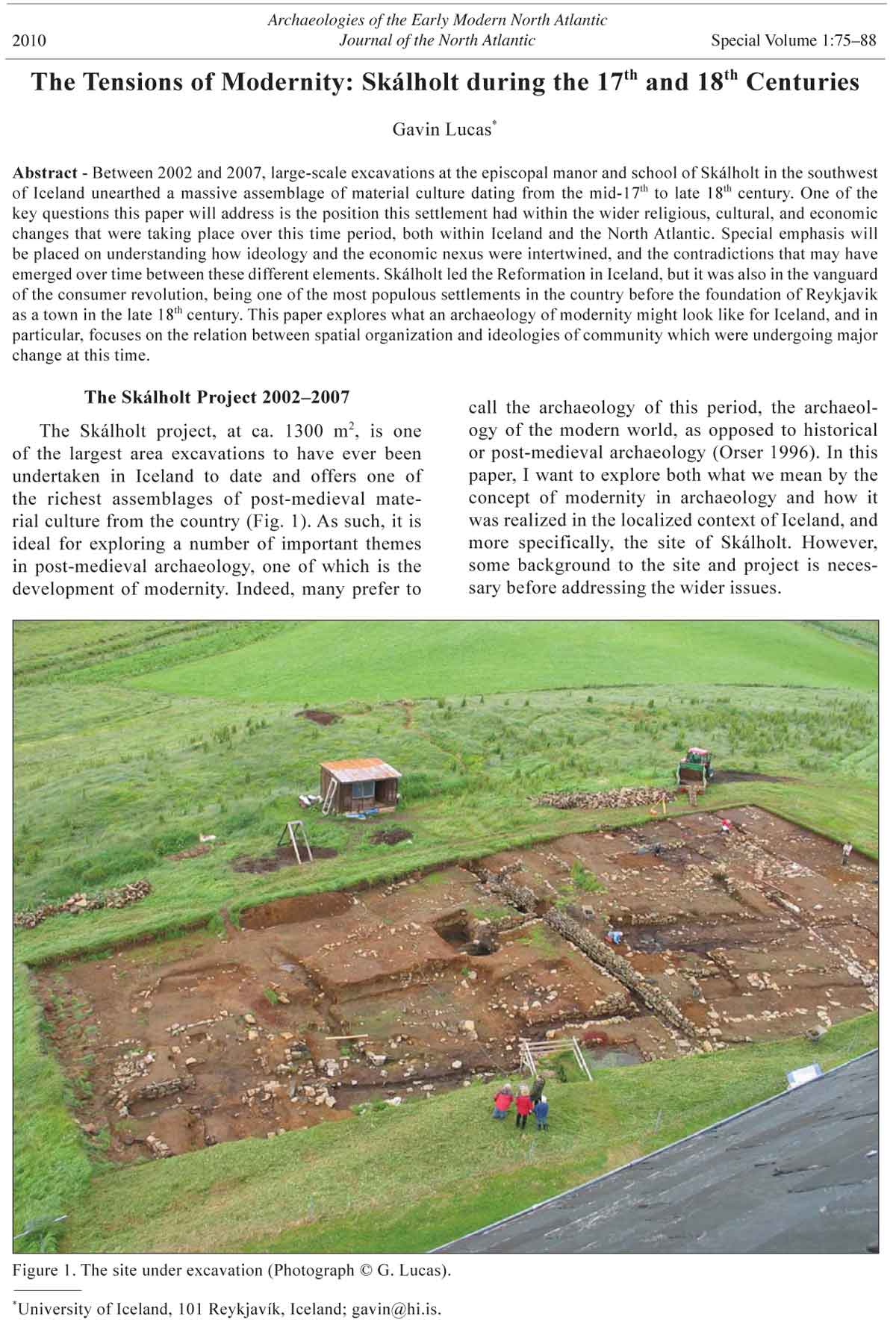

The Skálholt Project 2002–2007

The Skálholt project, at ca. 1300 m2, is one

of the largest area excavations to have ever been

undertaken in Iceland to date and offers one of

the richest assemblages of post-medieval material

culture from the country (Fig. 1). As such, it is

ideal for exploring a number of important themes

in post-medieval archaeology, one of which is the

development of modernity. Indeed, many prefer to

call the archaeology of this period, the archaeology

of the modern world, as opposed to historical

or post-medieval archaeology (Orser 1996). In this

paper, I want to explore both what we mean by the

concept of modernity in archaeology and how it

was realized in the localized context of Iceland, and

more specifically, the site of Skálholt. However,

some background to the site and project is necessary

before addressing the wider issues.

Figure 1. The site under excavation (Photograph © G. Lucas).

76 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1

Like elsewhere in Europe, archaeological research

on the post-medieval period in Iceland is

rather fragmentary (see Lucas and Snæsdóttir 2006

for a review). While the early years of archaeological

research were dominated by investigations of Viking

and Saga period sites, more anonymous and everyday

settlements, including sites from all periods,

were targeted beginning in the 1950s. This research

trend continued after the 1970s, but with a more selfconscious

reaction to literary-led research (Friðriksson

1994). Most of the work on post-medieval sites

or phases of sites dates from the late 1970s and

1980s continuing into the 1990s, and while much of

it comprises small-scale investigations, there are a

number of major sites from this time. These include

urban excavations in Reykjavík of the fi rst factory

from the 18th century (1971–5; Nordahl 1988),

the only complete excavation of a farm mound, at

Stóraborg (1978–90; Snæsdóttir 1989, 1991), and

investigation of three elite sites: the Danish colonial

Governor’s residence at Bessastaðir (1985–96;

Ólafsson 1991) and the rich farms of Viðey (1986-

94; Hallgrímsdóttir 1991, Kristjánsdóttir 1995) and

Reykholt (1987–9, 1998–2007; Sveinbjarnardóttir

2004). In 2000, there was further important work on

the Reykjavík factory prior to redevelopment of the

site, and in 2002, two new major projects began at

the episcopal estates of Hólar and Skálholt, as part

of a state-sponsored millennium celebration of the

adoption of Christianity in Iceland.

Skálholt, being one of the two episcopal sees in

Iceland was, until the late 18th century, also one of

the most important cultural and political centers in

the country (see Grímsdóttir 2006 for the most recent

and detailed history). The settlement dates back

at least to the 11th century, when it is mentioned in

documents as the farm of the fi rst Bishop, Ísleifur

Gissurarson, although it did not formally become an

episcopal seat until the late 11th/early 12th century.

Current excavations on the site have not reached

deep enough to provide archaeological evidence

for the origins of settlement, though palynological

research strongly indicates human presence in the

form of deforestation from the late 9th/early 10th

century AD (Einarsson 1962). Since the 12th century,

Skálholt remained the residence of the incumbent

bishop, and since at least the 16th century, there was

a seminary or Latin school at Skálholt housing at any

one time 20–40 students who lived there over the

winter months. The students were mostly sons of the

elite who went on to become priests or university students,

but also included a number of poorer students

whose costs were paid for by the Church. During

the late 17th century, there was also a printing press,

though this was short-lived. Besides the Bishop and

his household, the students and teachers, there were

also a large number of farm hands and servants who

provided daily subsistence and services for this large

estate, although much of the food and other goods

would have also come from neighboring farms in

the possession of Skálholt (Fig. 2). There was also

a trading station called Eyrarbakki on the coast ca.

40 km to the south, through which imported goods

arrived to the settlement. In the period 1602–1787,

there was a trade monopoly—only the subjects of

the king of Denmark could trade with Iceland and

only the ones that had leased the trade in a certain

area (Gunnarsson 1983).

In total, the average population at Skálholt was,

as far as is known, in excess of a hundred, which,

though small in a European or even North American

context, was unusually large by comparison to

most other places in Iceland. In terms of population

density, it was the closest thing to a town on the

island until Reykjavík claimed this title in the late

18th century. Skálholt inevitably played a major role

during the Reformation in Iceland—the fi rst Lutherans

were based there, and when the Danish Crown

instituted the Protestant Church on the island, a

counter-Reformation movement emerged, led by the

Bishop of Hólar. Throughout the 1540s there was

tension between Skálholt and Hólar, culminating in

the murder of the Bishop of Hólar and the killing of

Danish colonial offi cials. After 1551, the Reformation

of the Church was fi rmly established; nonetheless,

the Church in Iceland retained its right to tithes

and its administration remained as before, unlike in

Denmark (Ísleifsdóttir 1997). It was not until the

late 18th century that there was a real separation of

Church from State.

Natural disasters seem to bracket the period

on which the archaeological project is focused. In

1630, a major fi re destroyed most of the buildings

in the core settlement, and for the next 20 years, a

major re-building program was implemented. Then

in 1784, a massive earthquake shook the south of

Iceland and damaged large parts of the settlement

Figure 2. Properties owned by Skálholt ca. 1700 (Source:

Grímsdóttir 2006:90).

2010 G. Lucas 77

again; this time, it was decided to re-locate the

Episcopal seat and school to Reykjavík rather than

re-build. The school was moved to a timber house

in Hólavellir in Reykjavík (until 1804), while the

Bishop eventually moved into a stone house in

Laugarnes just outside the town in 1820. However

the earthquake was merely the trigger for a larger

scale re-organization of Church property, fi nally

concluding the policies of the Reformation. Such a

development was perhaps already prefi gured when

a bailiff was hired in the mid-18th century, creating

for a short time, a separation of the secular and religious

administration of Skálholt (Helgason 1936, ff.

78). However, it was not until the end of the century

that all the Skálholt farms were sold off (though the

Bishop personally purchased many of them) and

income for the Bishop and school now came directly

through the State treasury (Hálfdánarson 2005). In

1801, the Bishoprics of Hólar and Skálholt merged.

In terms of documentary sources, the history of

Skálholt is inevitably very rich, especially in comparison

to ordinary farms, and especially—as elsewhere

in Europe—from the 17th century and after.

Apart from the more general sources, such as land

registers and Church, State, and other administrative

documents, there were special inventories taken

of Skálholt in 1541, 1674, 1698, 1722, 1744, 1747,

1759, and 1764, which variously describe details

of buildings among other things, while the earliest

maps of the estate date from the 18th century.

In addition, there are numerous private papers of

the various Bishops including inventories of their

personal property. Only a small part of this material

has so far been studied in relation to the archaeology

and, of course, much of it has little direct bearing

on the remains; nonetheless, such textual evidence

provides an invaluable context against which to read

the archaeology.

As such a signifi cant historical place, the site

has attracted archaeological attention on a number

of occasions, fi rst at the start of the 20th century

when foundations for a new barn were laid (Jónsson

1894, 1904), and then in the 1950s prior to the

redevelopment of the site as a cultural center, when

the foundations of the medieval and post-medieval

cathedrals were excavated (Eldjárn et. al 1988).

In the 1980s, test trenches were dug into the farm

mound by the National Museum (Ólafsson 2002),

and a major open-area excavation of the farm mound

commenced in 2002, ending in 2007. These excavations

focused on the core of the post-medieval

settlement, which included the Bishop’s rooms and

a school. They uncovered a structural sequence from

the early 17th century up to the mid-20th century,

recovering over 60,000 artifacts and an estimated

100,000 faunal remains as well as extensive botanical

assemblages. Although post-excavation analysis

has only just begun, a preliminary overview of the

site can be given.

Currently the site has been divided into several

major phases spanning the 17th to 20th centuries, and

while on the whole, a remarkable degree of continuity

is exhibited, buildings were constantly being

modifi ed, some abandoned and some added (Fig. 3).

Basic continuity over the 17th and 18th centuries (and

possibly earlier) is expressed by an axial corridor

running the depth of the settlement from front to

back, creating a settlement of two halves. On the

eastern side was the school and on the western side

were the Bishop’s chambers; the same corridor doglegged

into a passage that exited in the Cathedral,

which stood at the top of the hill overlooking the

whole settlement. This kind of spatial form is common

to post-medieval farms in Iceland, and seems

to have origins in the late 14th and 15th centuries,

developing into what has been called the passage

house (gangabær; Fig. 4; Ólafsson and Ágústsson

2003) The spatial organization of Skálholt refl ects

this same vernacular architectural grammar, albeit

on a vastly larger scale and with differing room functions.

Perhaps the one unique element is its paved

courtyard in front of the Bishop’s rooms. Similarly

the building material is typically vernacular; most of

Figure 3. Structural phases of the core settlement (Drawing

by G. Lucas).

78 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1

the houses at Skálholt were built from turf/soil and

undressed stone with a timber frame supporting the

roof. In some ways, the settlement almost had the

appearance of being subterranean, with roofs and

walls merging with the ground, while inside was a

maze of rooms and connecting passages.

Floors were either ash/wood chip or wooden

boards, depending on the room, with stone paving

covering an intricate internal drainage system

running through most rooms. Of all the rooms

excavated from the 17th and 18th century, only the

school room had a built-in fire range, which was

later blocked in and replaced by a rather basic yet

unique under-floor heating system. Stove tiles from

other parts of the site indicate that at least some

other rooms (including the Bishops chambers) had

free-standing stoves as heating, and it is known

from documentary evidence that the 17th-century

bishop, Brynjólfur Sveinsson, also had a built-in

fire range (Ágústsson 1974). Large quantities of

window glass (some with painted text) indicate

that glazed windows were common for many of the

rooms, while iron fixtures such as locks and hinges

indicate degrees of privacy or control of access.

While the basic layout of the settlement remained

unchanged during the 17th and 18th centuries,

there were subtle changes, which affected access and

movement inside. Most noticeable and signifi cant

was a gradual separation of the two halves (School

and Bishop), as doorways and connecting passages

on either side of the main corridor were sealed off.

What this means is diffi cult to say at present, but it

undoubtedly refl ects changing relationships between

the different parts of the population living there.

Certainly, there was some documented friction between

the last bishop residing there and the schoolmaster

(Helgason 1936).

The amount and quality of material culture,

though perhaps unremarkable for an urban context on

mainland Europe or North America, is quite unusual

in Iceland and attests to the role of Skálholt in leading

new consumption patterns for the country. Pottery imports

include Chinese porcelain, German stonewares,

Dutch tin-glazed earthenwares, and plain glazed

Figure 4. Plan of Icelandic passage farmhouse from the late 17th century at Sandártunga (Source: Eldjárn 1951).

2010 G. Lucas 79

earthenwares and slipwares from Denmark and Germany.

A large portion of the ceramics are tablewares

(jugs, cups, bowls, and plates) rather than cooking

vessels, and most of it probably personal possessions

rather than institutional. Other tableware includes a

wide collection of glassware (wine bottles, prunted

beakers, stemware, painted fl asks, engraved beakers,

and lattimo bowls) and cutlery. Dress items are also

very common, especially buttons (glass, wooden,

and metal types, many elaborately decorated), beads

(glass and mineral), and various copper fastenings.

Good organic preservation has also provided a substantial

assemblage of woven textiles and leather.

Other personal items include clay pipes, found in

abundance and mostly sourced to Holland but also

some from Denmark, while in the School, many student

writing quills were found along with pumice for

cleaning inky hands.

This brief summary of the site and its fi nds

has hopefully given a sense of the archaeology at

Skálholt. For the remainder of this paper, I use this

material to explore the concept of modernity in an

archaeological context and how it was realized at the

local level.

The Archaeology of Modernity

Modernity is somewhat of a popular concept employed

by archaeologists today, particularly as a way

of describing the period after ca. 1500 AD. However,

there has been rather less explicit discussion about

what this term actually means, no doubt partly because

it has such wide and general currency in everyday

language, and partly because it is a term that

can mean so many different things. Charles Orser

provides one of the fi rst and most explicit statements

in archaeology, largely framing his discussion in the

context of economic theories of development that

emerged in the 1950s and 1960s (Orser 1996:81–5).

Modernization or development theory in this sense

was (and is) primarily about how to stimulate the

social and economic development of Third World

countries. It became the subject of major critique

because it ignored the effects of global inequalities

created through the development of one nation at the

expense of another, as argued by dependency theorists

and world systems theorists. There is no doubt

that globalization is closely linked to modernization,

and Orser himself sees modernization as just one of

four inter-related concepts (colonialism, eurocentrism,

and capitalism being the other three). The

usefulness of modernization theory was explored

more explicitly in a paper by Cabak, Groover, and

Inkrot, who looked at modernization in a rural area

of South Carolina between 1875 and 1950 (Cabak et

al. 1999). What is of particular interest in their study

is their discovery of two tempos, macro and microlevel

changes, the former largely referring to the

built environment of architecture and other major

landscape features, the latter to everyday goods and

consumables. They found that while there had been

little or no modernization in terms of landscapes

and architecture up to 1950, there had been a steady

movement towards modern lifestyles in terms of

everyday commodities.

While such approaches to modernization are

important, they are, however, also limiting. For

modernity as expressed through modernization or

development theories tend to over-emphasize the

economic at the expense of the ideological manifestations

of modernity. Even though Cabak et al.

(1999) explicitly expand the concept of modernization

to incorporate ideological elements, their

discussion is largely framed within the context of

technological developments, whether in farm machinery

or consumer goods. By contrast, it is the

ideological perspective on modernity that dominates

most of the discussion of modernity in philosophy

and social theory. It is impossible to present any

overall consensus on this subject, but it is quite clear

that a number of important themes recur, such as the

development of science and philosophies of reason

along with the increasing secularization of thought

and practice. Habermas highlighted three key developments

in the emergence of modernity, which

capture much of this change: the Renaissance, the

Reformation and the discovery of the New World

(Habermas 1985). More importantly, Habermas also

defi ned modernity as fundamentally an expression

of a new time-consciousness, particularly experienced

as a rupture of the present from the past (hence

“modernity”). I fi nd this an extremely useful point to

start thinking about this issue, especially as one can

see how his three events combined to foster this new

time-consciousness: the Renaissance and Reformation

forging a break with tradition, and the discovery

of the New World revealing a past with no ostensible

connection to the present. Yet this rupture was by

no means absolute, but always tempered by an opposing

tendency—to reconcile religion and reason/

science, the State and the Church, new worlds/

prehistory with Classics or the Scriptures. Indeed,

modernity is perhaps characterized not simply by a

new time-consciousness that separated the past from

the present, but simultaneously an unease about this

rupture and the corresponding anxiety that being

“modern” meant being separated from the past.

Arguably, the most important idea in resolving

this unease has been the concept of progress. Progress

allows one to articulate the relation between

the present and past in such a way as to preserve

both change and continuity; to be modern is to be

not just different but better—and better implies a

common ground allowing one to perceive both the

80 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1

connection of present to the past, but simultaneously,

its difference. The 19th century—as the century

of progress—is perhaps the zenith of modernity; it

certainly comes across as the period when people

had most faith and confidence in their present (and

future). Sarah Tarlow (2007) has recently explored

how the notion of progress, or more specifically improvement,

was articulated in a wide range of material

conditions and offers us perhaps the most useful

archaeological example of what modernity means

for this period. Showing how the ideology of improvement

worked at multiple levels from farming

practice to town planning and from domestic lifestyles

to personal development, her book provides

rich ground for thinking through modernity as a

specific historical condition. However, the preceding

argument does suggest that what characterizes

modernity is not the same throughout the period

we usually designate as Modern; modernity itself

changes. The ideology of improvement only weakly

applies if at all to the 17th century or late 20th

century. Danny Miller’s work in Trinidad, where

he explored the articulation of modernity through

material culture in a local context in the late 20th

century is a case in point. Miller suggested that modernity

was largely expressed through a dualism in

people’s lives, which he defined through the terms

transience and transcendent (Miller 1994). On the

one hand, Trinidadians were concerned with the

longer-term perspective, establishing roots through

fixed or highly normative types of consumption

patterns, for example, in relation to the domestic interior,

especially the living room. On the other, they

liked to live for the moment and express this particularly

through clothing, which is often designed

and worn for a specific one-off event. However, as

Miller argues, transcendence and transience can be

found in the same sites, depending on the individual,

and such values are not fixed to any particular

form of consumption. In the next section, I want to

explore the concept of modernity as it might apply

to Iceland and more specifically, one site in Iceland

(Skálholt), but taking a longer-term perspective.

The Movement Towards Modernity in Iceland

In 2007, Iceland was ranked as the most developed

nation on earth by the United Nations Human

Development Index (UNDP 2007:229). A century

earlier, most of the population of Iceland still lived

a rural lifestyle on turf farms. There is no doubt that

the 20th century was a period of rapid change for

Iceland, and despite developments in preceding centuries,

it was not until the late 19th and 20th centuries

that industrialization and urbanization had any real

presence on the island (Jónsson 2004). In the mid-

18th century, there was an abortive attempt to stimulate

the Icelandic economy by the establishment

of a joint stock company which came to be known

as Innréttingar (“New Enterprises”). It focused its

efforts towards promoting industrial textile production

and set up a factory on the farm of Reykjavik

(Róbertsdóttir 2001). Although it was never really

successful, it continued in operation for more than

half a century and, more importantly, was the catalyst

for the development of the fi rst urban settlement

in Iceland, transforming Reykjavik from a farm to a

town. However, while Reykjavik grew over the 19th

century, both as an administrative and commercial

center, the rest of Iceland remained fundamentally

rural until the end of the 19th and early 20th century.

Perhaps the most signifi cant changes for Reykjavik

only occurred in the latter half of the 19th century,

initially with the opening of free trade and the arrival

of foreign merchants in the 1850s. The real industrial

revolution arrived with the advent of British

fi shing trawlers in ca. 1890 and foreign loan capital

in 1904; over the fi rst three decades of the 20th century,

Icelandic fi shing became mechanized, leading

to massive increases in catch and the need for labor

to process this catch—all largely geared towards an

export economy (Jónsson 1980, Magnússon 1985).

With economic growth, came rising population and

settlement nucleation (Fig. 5), but it was a gradual

process. Throughout the 19th century, most people

still lived in turf houses—even in Reykjavik. As

late as 1910, over half the houses in Reykjavik were

still built from turf, and it was only in the 1930s that

turf was superseded by stone and concrete housing

at a national level (Fig. 6). From the 1930s and especially

after the Second World War, the domestic

economy diversifi ed, leading to the rise of a modern

consumer society (Jónsson 2004, 2007).

Although important, this economic and statistical

history is a limiting perspective on modernization,

which as argued above, ought to be seen as a

Figure 5. Graph showing development of settlement nucleation

and urbanization in Iceland, 1890–1990 (Source:

Hagskinna, table 2.10).

2010 G. Lucas 81

much broader and longer-term process. For example,

even though one might describe turf houses as traditional

in contrast to stone and concrete housing,

this does not mean there were no changes within

vernacular architecture that might be described as

modernizing. At the end of the 18th century, Guðlaug

Sveinsson wrote an article for the Danish Royal Literary

Arts Society, describing and promoting a new

type of look for the traditional farm, which presented

a multiple-gable façade (Sveinsson 1791). Although

gables on farmsteads seem to date back to the 14th

century, what was particularly new here was the idea

of an array of adjacent gables, presenting a clear

façade to the farm, emphasizing a frontage (Fig. 7).

There are two things to note here. First, the notion of

a house accentuating its façade can be seen as part of

a much wider trend in European architecture linked

to neo-classical ideals (see Lucas and Regan 2003

for an example of an English farmstead conversion

along these lines). Second, what is particularly striking

about the Icelandic gabled farmhouse, as it swept

the country over the 19th century, is its allusion to a

city street frontage (Fig. 8). Even though the farm remained

a single isolated unit, and the rooms behind

the façade were invariably workshops of one sort

or another, the citation to urban street architecture

is remarkable. In both of these ways—as a part of

a wider phenomenon emphasizing the façade, and a

more localized interpretation—the 19th century rural

house, though still built with traditional materials,

was adopting a distinctly modernizing form.

Much the same points can be made in respect

to the consumption of everyday goods. One of the

important changes to occur over the 19th century was

a shift in the diet from animal-based to vegetablebased

products, specifi cally from a traditional diet of

Figure 7. Guðlaug Sveinsson’s plan for the new gabled farm, 1791 (Source: Sveinsson 1791).

Figure 6. Graph showing change from vernacular turf to

stone and concrete housing in Iceland 1910–1960 (Source:

Hagskinna, table 7.3).

82 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1

To further develop these ideas, I want to explore

how modernity developed in the 17th and 18th centuries

in Iceland, through the example of Skálholt.

Inevitably, taking one site as an exemplar exposes

itself to problems of over-generalization, so two

qualifi cations need to be made. First, there are almost

no comparable studies conducted in Iceland to

draw on, and indeed any work of a more interpretive

nature on the archaeology of this period (beyond

excavation reports) is striking by its absence (see

Lucas and Snæsdóttir 2006 for a recent review).

Second, Skálholt as an élite and relatively large

settlement is undoubtedly unusual, making it even

more problematic as an example of wider processes

occurring in Iceland at this time. Yet for the same

reason, it may also be one of the best and few examples

for this period—if one regards a modernizing

consciousness as one which fi rst emerges within

élite society. In general, the desire for modernizing

at Skálholt can be associated with the fact that it was

an elite settlement, part of whose population were

well connected to élites in mainland Europe (especially

Denmark) and thus would have been familiar

with current cultural movements. However, as with

archaeological studies within Iceland, comparative

work in Denmark to draw on for this topic is hard to

fi nd; research interest in post-medieval archaeology

in Denmark has only just begun (e.g., Andersen and

Moltsen 2007, Courtney 2006, Høst-Madsen 2006).

fi sh and dairy produce to one where cereal and vegetables

constitute the greater part (Jónsson 1997).

Moreover, other products like tobacco, coffee, and

sugar became increasingly more available to the

majority of the population. Changes to diet is one

thing; however, another concerns the style of eating

and drinking; it is here that one can perhaps discern

more readily the development of a modernizing attitude.

Very little is known about traditional ways of

eating, but certainly by the late 18th and 19th centuries,

individual containers were common—wooden,

stave-built bowls called askar, often ornately carved

and highly personal, held food which was eaten

from the lap with an equally personalized wooden

or horn spoon. With the introduction of cheap, mass

produced industrial ceramics from the late 19th century,

ceramic bowls and plates seem to have gradually

replaced the wooden bowls, but were probably

used in much the same way (i.e., on the lap). It was

only much later in the 20th century that most people

started to sit regularly at tables to eat with cutlery

(Lucas 2007). Nonetheless, the adoption of individual

containers, i.e., askar, can be seen as part of

a wider European shift from communal to individual

eating habits that developed from the 16th and 17th

centuries, regardless of whether this was on the

table or lap (Deetz 1996). As such, askar might be

seen as another example of localized development of

vernacular material for a more modern function.

Figure 8. A 19th-century gabled farm at Grenjaðarstaður, Iceland on the left and a 17th-century gabled town house in Copenhagen

on the right (Photographs © G. Lucas).

2010 G. Lucas 83

case arrayed along the main thoroughfare, which

would seem to support the interpretation that these

facades were citing urban architectural forms. While

Skálholt was not a city by any defi nition, it was one

of the most densely populated settlements in the

country with a diverse composition of people. It can

be argued that if the 19th century gabled farmhouse

was citing townhouse architecture, Skálholt was taking

this one step further and citing the appearance

of a village or town insofar as its facades actually

fronted a thoroughfare.

If this pseudo-urban form can be taken as a sign

of a modernizing consciousness, one needs to bear

in mind that the real town in Iceland (i.e., Reykjavík)

was growing up ca. 80 km to the west. Indeed, it is

no coincidence that Skálholt was effectively abandoned

at the same time as Reykjavík was emerging

as the fi rst urban center on the island. There were of

course wider political and economic reasons for this

(the earthquake aside), but it is important to consider

how these were linked to concrete materialities. In

this section, I will draw on the ideas of Edward Soja

and in particular, his concept of synekism (Soja

2000:12–15). Soja argues for the importance of the

spatiality of the urban form to social, political, and

economic life—not just refl ective but constitutive. In

the context of the 18th and 19th centuries in particular,

Soja sees the city as a critical part of the expression

of modernity and what it meant to be a citizen:

cityspace embodied a certain conception of society

(Soja 2000:74–5). Soja’s concept of synekism generalizes

this and encapsulates the broad notion of community

or living together, after the original Greek.

The important question I want to draw from his work

in the context of Iceland is quite simple: what kind

of synekism is forged by the spatial organization at

Skálholt and how does this differ to that which was

emerging in Reykjavík? In many ways, the answer to

this question will help us to understand the specifi c

articulation of modernity at Skálholt.

It is instructive to compare the spatial organization

of Skálholt with Reykjavík from maps drawn

up at a similar date. In 1784, a map of Skálholt was

draughted one year before the abandonment of the

settlement and the relocation of it primary functions

to Reykjavík (Fig. 9). In 1786, Reykjavík was offi -

cially founded as the fi rst town by royal decree, and

the following year in 1787, a plan was published

(Fig. 11). If one compares the spatial layout of these

two places, the differences are fairly clear. Skálholt

very much exhibits a concentric spatiality: at the

center lies the church, with the school and Bishop’s

manor alongside it, together forming an inner core.

Enclosing these elements is an outer ring of workhouses

and outhouses, which in many cases, face

on to a thoroughfare, which is bounded by a boundary

wall. One can even extend this concentricity

This study is thus inevitably limited and should

be seen as a preliminary exploration of the issue

rather than a detailed analysis; it is hoped that future

research on a range of settlement types both in Iceland

and Denmark from this time period will expand

our understanding of this modernizing consciousness

and consequently, of its particular manifestation

at Skálholt. These qualifi cations aside, there are

many aspects of this consciousness one could examine;

for example, analysis of the faunal assemblage

from the site has revealed interesting experimentation

with cattle breeds, refl ecting obvious links to

wider trends in agricultural improvement as well

as Enlightenment biology (Hambrecht 2006; also

Hambrecht, this volume). Similar experiments with

barley cultivation are indicated by the palynological

record (Einarsson 1962). Both of these clearly show

modernist ideologies of science and reason being applied

to agriculture, and indeed wider European discourse

on agricultural improvement was not absent

from Iceland (Halldórsson 1983). Similarly, various

regulations for educational and self improvement

were published in the latter half of the 18th century

(largely drawn up by one person, a Danish pastor

Ludvig Harboe), including a dietary table for the

students at Skálholt (Stephensen and Sigurðsson

1853–1889). At the same time, however, it is clear

that such movements had to be adapted into local

conditions—and traditions—and it is precisely this

tension which I will bring out in my discussion below.

For this paper, I will concentrate on one aspect

in which modernity was articulated in the local context:

the built environment.

Modernity and Space:

The Contradictions of Skálholt

Architecturally, the layout of Skálholt is very

traditional; it is typologically a passage farm, but

on a much larger scale. At the time the settlement

was abandoned in 1784, the new gabled style was

only just being promoted, yet it is quite clear from

a contemporary map that arrayed gabled frontages

lined the main thoroughfare which passed along

the southern edge of the settlement (Fig. 9). These

gabled buildings, however, were not part of the main

structure like a typical gabled farmhouse, but instead

were separate buildings, chiefl y workshops and other

outhouses. Contemporary sketches and paintings of

the site unfortunately are from the opposite side, so

we cannot be sure exactly how these gable fronts appeared—

an earlier perspective plan (from ca. 1700)

that shows buildings in the same position gives some

indication (Fig. 10), but the buildings have certainly

changed and thus it cannot be used as a reliable guide

to appearance. However, the important element here

is the presence of multiple gabled frontages, in this

84 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1

The spatiality of Reykjavík is quite different.The

new town, even though small and consisting at this

point of just one street, nevertheless contains the

germ of a typical Renaissance and post-Reformation

urban spatiality. It appears linear (soon to be gridlike),

but more importantly, it is polycentric rather

than concentric; it has multiple foci, and here the

church is just one of these centers, along with the

outward to include all the neighboring properties

that were owned by Skálholt. What is imparted is

in effect the centripetal power of the church radiating

out, but also as one moves outward, a shift from

the religious to the secular. There is a worldview

encapsulated in this concentric spatiality, one that

underlines the central role of the church and religion

in political and social life (Fig. 12).

Figure 9. 1784 map of Skálholt by Steingrímur Jónsson (Original in the National Archives of Iceland).

2010 G. Lucas 85

Figure 10. Circa 1700 map of Skálholt (Original in the National Archives of Iceland).

Figure 11. 1786 map of Reykjavik by

Rasmus Lievog (Original in the National

Archives of Iceland).

86 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1

nally it may have developed as a center, internally

its space remained polycentric in contrast to the

internal concentric spatiality of Skálholt. What is

important in the polycentricity of Reykjavík is how

it incorporated a more dispersed sense of power and

more segregated sense of society—no longer did

the church enfold all social functions within it, but

rather education, justice, religious practice, commerce,

and so on, were regarded as separate parts

of society. Of course one needs to temper this with

the broader political reality of the day: Iceland was

still a colony of Denmark, which remained an absolutist

state until the 1830s. Nonetheless, Iceland

was largely run through an oligarchy of bureaucrats

whose power was increasingly more signifi cant as

that of the Church waned; as such, the polycentric

space of Reykjavík was immeasurably more suited

to this form of power.

This brief discussion of the different spatialities

of Reykjavík and Skálholt has attempted to emphasize

the role of space in how a community lives

together and perceives itself. It is clear that the two

places are very different in nature, but they also

shared many similarities. Their population sizes at

the time were not greatly different: in 1786, Reykjavík

is recorded as having a population of 289, but

this includes several farms as well as the town itself;

by comparison, Skálholt parish lists 180, though

this also includes neighboring farms. Both settlements

also hosted a range of different activities and

possessed diversity in community composition (i.e.,

people from different social scales). Yet it seems

that one was also much better suited as a place for

living together within the changing ideology of

what a modern society was perceived to be. Skálholt

was clearly a place that grappled with modernity—

agricultural innovation, even some architectural innovation,

to say nothing of being a major consumer

of goods manufactured in the north European cities.

However, the tension between breaking with the past

to forge a new present/future was conceivably too

much to deal with. Indeed, one can see that the emphasis

on improving more traditional activities such

as agriculture rather than commerce and industry (as

in Reykjavik) suggests that modernization was only

applied within the limits of tradition. Agriculture

was regarded as the center of gravity for Icelandic

society, even well into the 19th century, yet both

the tenancy system and strict labor laws acted as an

impediment to any real agricultural improvement

until the end of the 19th century (Jónsson 1993). No

amount of Enlightenment experimental breeding

would engender change if the social organization of

rural society remained intact. Forces within the community

were also divided—historically documented

rifts between the steward and the bishop and schoolmaster

and bishop, an archaeologically attested

trading station, textile factory, a jail, and school.

As with Skálholt, this polycentricity can initially be

extended outward to other neighboring places such

Viðey (treasurer’s residence), Bessastaðir (colonial

governor’s residence) or Nes (residence of the director

of public health). No single part dominates,

but rather there is a connected network of centers

according to segregated functions—it is what one

might call a heterarchical space (Fig. 13). Nonetheless,

it is also clear that Reykjavík as a whole

increasingly functions more concentrically—fi rst

in drawing the Bishopric and school from Skálholt

(1785), then the Law courts from Þingvellir (1800),

fi nally—and most signifi cantly—the colonial governor

from Bessastaðir (1815). However, while exter-

Figure 12. Diagrammatic representation of concentric

space of Skálholt (Drawing by G. Lucas).

Figure 13. Diagrammatic representation of polycentric

space of Reykjavik (Drawing by G. Lucas).

2010 G. Lucas 87

Ísleifsdóttir, V.A. 1997. Siðbreytingin á Islandi 1537–

1565. Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, Reykjavík, Iceland.

393 pp.

Jónsson, B. 1894. Skálholt. Árbók hins Íslenzka Fornleifafélags

1894:3–6.

Jónsson, B. 1904. Fornleifafundir í Skálholti 1902. Árbók

hins Íslenzka Fornleifafélags 1904:20–21

Jónsson, G. 1993. Institutional change in Icelandic agriculture

1780–1940. Scandinavian Economic History

Review XLI:101–28.

Jónsson, G. 1997. Changes in food consumption in Iceland

ca. 1770–1940. Pp. 37–60, In R.J. Söderberg

and L. Magnusson (Eds.). Kultur och Konsumtion i

Norden 1750–1950. Finska historika samfundet, Helsingfors,

Sweden. 274 pp.

Jónsson, G. 2004. The transformation of the Icelandic

economy: Industrialisation and economic growth

1870–1950. Pp. 131–166, In S. Heikkinen and J.L. van

Zanden (Eds.). Exploring Economic Growth: Essays

in Measurement and Analysis; A Festschrift for Riitta

Hjerppe on her 60th Birthday. Academic Publishers,

Amsterdam, Holland. 384 pp.

Jónsson, G. 2007. Hvenær varð neysluþjóðfélagið til? Pp.

69–78, In B. Eyþórsson and H. Lárusson (Eds.). Þriðja

íslenska söguþing 18–21 mai 2006. Sagnfræðingafélag

Íslands, Reykjavík, Iceland. 524 pp.

Jónsson, S. 1980. The development of the Icelandic fi shing

industry, 1900–1940, and its regional implications.

Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. University of Newcastle

upon Tyne, UK.

Kristjánsdóttir, S. 1995. Klaustureyjan á Sundum. Árbók

hins íslenzka fornleifafélags 1994:29–52.

Lucas, G. 2007. The widespread adoption of pottery in

Iceland 1850–1950. Pp. 62–68, In B. Eyþórsson and

H. Lárusson (Eds.). Þriðja íslenska söguþing 18–21

mai 2006. Sagnfræðingafélag Íslands, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 524 pp.

Lucas, G., and R. Regan. 2003. The Changing Vernacular:

Archaeological excavations at Temple End, High Wycombe,

Buckinghamshire. Post-Medieval Archaeology

37:165–206.

Lucas, G., and M. Snæsdóttir. 2006. Archaeologies of modernity

in the land of the sagas. Meta 3:5–18.

Magnússon, M.S. 1985. Iceland in Transition: Labour and

Socio-economic Change before 1940. Ekonomiskhistoriska

föreningen, Lund (Skrifter XLV), Sweden.

306 pp.

Miller, D. 1994. Modernity. An Ethonographic Approach.

Berg, Oxford, UK. 340 pp.

Nordahl, E. 1988. Reykjavík from the Archaeological

Point of View. Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis,

Uppsala, Sweden. 150 pp.

Ólafsson, G. 1991. The excavations at Bessastaðir 1987.

The colonial offi cial’s residence in Iceland. Acta Archaeologica

61:108–115.

Ólafsson, G. 2002. Skálholt. Rannsóknir á bæjarstæði

1983–1988. Þjóðminjasafn Íslands, Reykjavík, Iceland.

22 pp.

Ólafsson, G., and H. Ágústsson. 2003. The Reconstructed

Medieval Farm in Þjórsárdalur and the Development

of the Icelandic Turf House. National Museum of Iceland,

Reykjavík, Iceland. 35 pp.

Orser, C. 1996. A Historical Archaeology of the Modern

World. Plenum Press, New York, NY, USA. 247 pp.

increasing separation of the Bishop’s wing from the

school—these can be linked to different outlooks on

the nature of what kind of community there should

be at Skálholt. In the end, the very spatiality of the

settlement favored tradition and it is perhaps inevitable

that to complete the rupture with the past, the

key functions of Skálholt were re-located to a new

site for a new start.

Literature Cited

Ágústsson, H. 1974. Meistari Brynjólfur byggir ónstofu.

Saga XII:12–68.

Andersen, V.L., and A. Moltsen. 2007. The dyer and the

cook: Finds from 8 Pilestræde, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Post-Medieval Archaeology 41:242–63.

Cabak, M., M. Groover, and M. Inkrot. 1999. Rural Modernization

during the recent past: Farmstead archaeology

in the Aiken plateau. Historical Archaeology

33:19–43.

Courtney, P. 2006. Europe: Denmark. Society for Historical

Archaeology Newsletter 39: 27.

Deetz, J. 1996. In Small Things Forgotten. Anchor Books,

New York, NY, USA. 284 pp.

Einarsson, Þ. 1962. Vitnisburður frjógreiningar um gróður,

veðurfar og landnám á Íslandi. Saga III:442–69.

Eldjárn, K. 1951. Tvennar bæjarrústir frá seinni öldum.

Árbok hins islenzka fornleifafélags 1949–50:102–

119.

Eldjárn , K., H. Christie, and J. Steffensen. 1988. Skálholt.

Fornleifarannsóknir 1954–1958. Lögberg, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 228 pp.

Friðriksson, A. 1994. Sagas and Popular Antiquarianism

in Icelandic Archaeology. Avebury, Aldershot, UK.

212 pp.

Grímsdóttir, G. 2006. Biskupsstóll í Skálholti. Pp. 21–

427, In G. Kristjánsson and Ó. Guðmundsson (Eds.).

Saga Biskupsstólanna. Bókaútgáfan Hólar, Hólar,

Iceland. 864 pp.

Gunnarsson, G. 1983. Monopoly Trade and Economic

Stagnation. Studies in the Foreign Trade of Iceland

1602–1787. Ekonomisk-historiska föreningen, Lund,

Sweden. 190 pp.

Habermas, J. 1985. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity.

Polity Press, Cambridge, UK. 430 pp.

Hálfdanarson, G. 2005. Sala Skálholtsjarða. Fyrsta uppboð

ríkiseigna á Islandi, 1785–98. Saga XLIII:71–97.

Halldórsson, B. 1983 [1780]. Atli, eður ráðagjörðir yngismanns

um búnað sinn. Reprinted in Rit Björns

Halldórssonar í Sauðlauksdal, Búnaðarfélag islands,

Reykjavík, Iceland. Pp. 49–211.

Hallgrímsdóttir, M. 1991. The excavation on Viðey, Reykjavík,

1987–1988. A preliminary report. Acta Archaeologica

61:120–125.

Hambrecht, G. 2006. The Bishop’s beef: Improved cattle

at early modern Skálholt, Iceland. Archaeologia Islandica

5:82–94.

Helgason, J. 1936. Hannes Finnsson. Biskup í Skálholti.

Ísafoldarprentsmiðja H.F., Reykjavík, Iceland. 272 pp.

Høst-Madsen, L. 2006. An 18th-century timber wharf on

Copenhagen Harbour. Post-Medieval Archaeology

40:259–71.

88 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 1

Róbertsdóttir, H. 2001. Landsins Forbetran: Innréttingarnar

og Verkþekking í Ullarvefsmiðjum Átjándu

aldar. University of Iceland Press, Reykjavík, Iceland.

280 pp.

Snæsdóttir, M. 1989. Stóraborg. En presentation. Hikuin

15:53–58.

Snæsdóttir, M. 1991. Stóraborg—An Icelandic farm

mound. Acta Archaeologica 61:116–20.

Soja, E.W. 2000. Postmetropolis. Critical Studies of Cities

and Regions. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK.

440 pp.

Stephensen, O., and J. Sigurðsson (Eds.). 1853–1889.

Lovsamling for Island: Indeholdende Udvalg af

de vigtigste ældre og nyere Love og Anordninger,

Resolutioner, Instruktioner og Reglementer, Althingsdomme

og Vedtægter, Kollegial-Breve, Fundatser og

Gavebreve, samt andre Aktstykker til Oplysning om

Islands Retsforhold og Administration i ældre og nyere

Tider. Höst, Kjöbenhavn, Denmark. 21 volumes.

Sveinbjarnadóttir, G. 2004. Interdisciplinary research

at Reykholt in Borgafjörður. Pp. 93–98, In G.

Guðmundsson (Ed.). Current Issues in Nordic Archaeology.

Proceedings of the 21st Conference of Nordic

Archaeologists. Félag íslenskra fornleifafræðinga,

Reykjavík, Iceland. 214 pp.

Sveinsson, G. 1791. Um húsa- eðr Bæja-byggingar á Íslandi,

sérdeildis smá- eðr kot-bæa. Rit þess konungliga

íslenska Lærdómslistafélags XI:242–88.

Tarlow, S. 2007. The Archaeology of Improvement in

Britain, 1750–1850. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, UK. 222 pp.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2007.

Human Development Report 2007/2008. Palgrave

Macmillan, New York, NY, USA. 399 pp.