2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 161

Introduction

The literature of the medieval Icelanders gives a

unique insight into the history, culture, and religion

of the North Atlantic Norse. It conveys the medieval

Icelanders’ perception of themselves and their past.

For good and bad, it is the insiders’ view (Hreinsson

1997, Kristjánsson 1988, Ólason 1998).

Archaeology does not have the same explanatory

power as the written word when it comes to exploring

the mentality of people in the past. However, despite

its shortcomings, archaeology may still convey

valuable information about the mindset of the Viking

and medieval Norse. Can the Norse peoples’ use of

the landscape tell us something about their values

and beliefs?

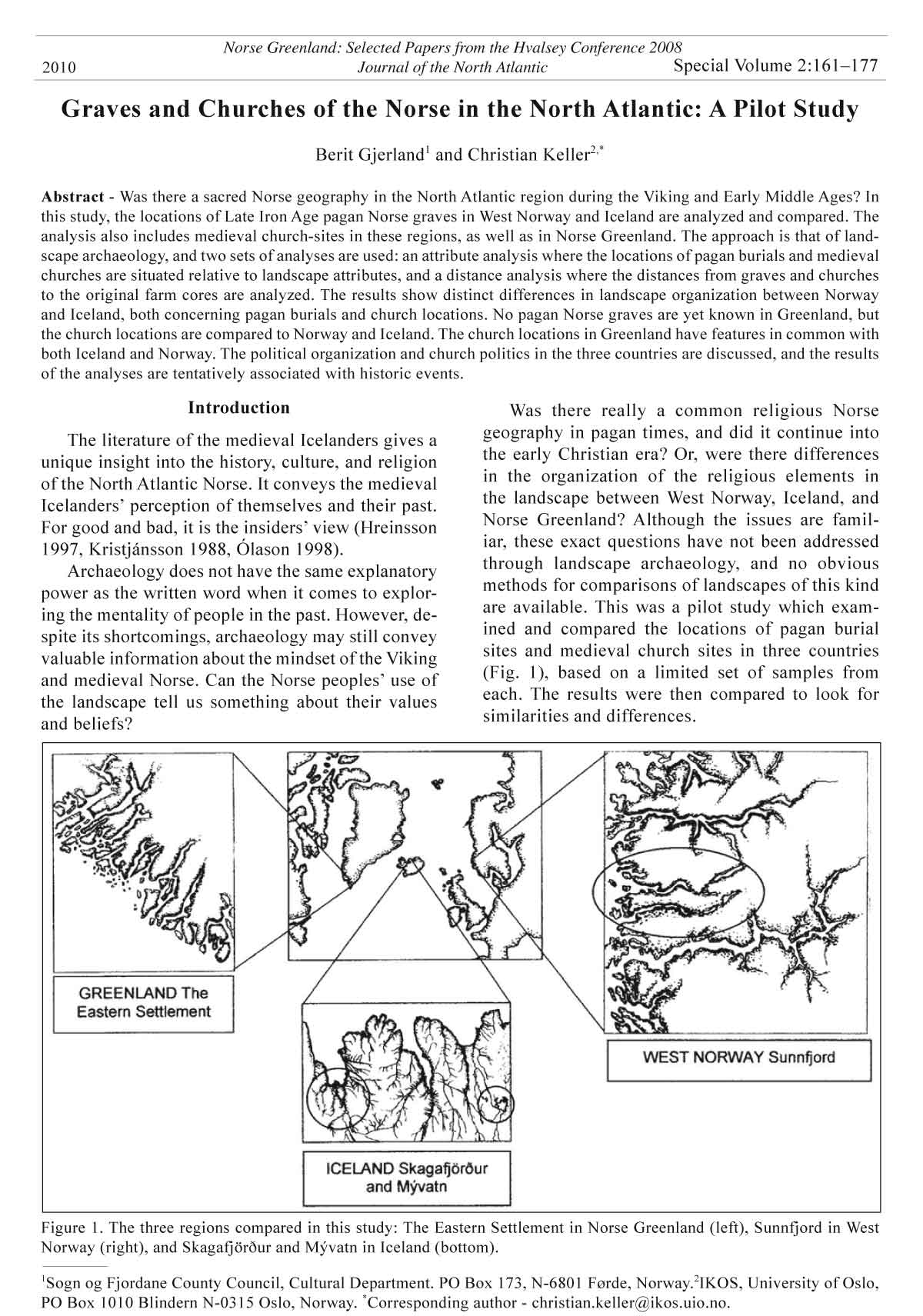

Was there really a common religious Norse

geography in pagan times, and did it continue into

the early Christian era? Or, were there differences

in the organization of the religious elements in

the landscape between West Norway, Iceland, and

Norse Greenland? Although the issues are familiar,

these exact questions have not been addressed

through landscape archaeology, and no obvious

methods for comparisons of landscapes of this kind

are available. This was a pilot study which examined

and compared the locations of pagan burial

sites and medieval church sites in three countries

(Fig. 1), based on a limited set of samples from

each. The results were then compared to look for

similarities and differences.

Graves and Churches of the Norse in the North Atlantic: A Pilot Study

Berit Gjerland1 and Christian Keller2,*

Abstract - Was there a sacred Norse geography in the North Atlantic region during the Viking and Early Middle Ages? In

this study, the locations of Late Iron Age pagan Norse graves in West Norway and Iceland are analyzed and compared. The

analysis also includes medieval church-sites in these regions, as well as in Norse Greenland. The approach is that of landscape

archaeology, and two sets of analyses are used: an attribute analysis where the locations of pagan burials and medieval

churches are situated relative to landscape attributes, and a distance analysis where the distances from graves and churches

to the original farm cores are analyzed. The results show distinct differences in landscape organization between Norway

and Iceland, both concerning pagan burials and church locations. No pagan Norse graves are yet known in Greenland, but

the church locations are compared to Norway and Iceland. The church locations in Greenland have features in common with

both Iceland and Norway. The political organization and church politics in the three countries are discussed, and the results

of the analyses are tentatively associated with historic events.

Special Volume 2:161–177

Norse Greenland: Selected Papers from the Hvalsey Conference 2008

Journal of the North Atlantic

1Sogn og Fjordane County Council, Cultural Department. PO Box 173, N-6801 Førde, Norway.2IKOS, University of Oslo,

PO Box 1010 Blindern N-0315 Oslo, Norway. *Corresponding author - christian.keller@ikos.uio.no.

2010

Figure 1. The three regions compared in this study: The Eastern Settlement in Norse Greenland (left), Sunnfjord in West

Norway (right), and Skagafjörður and Mývatn in Iceland (bottom).

162 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

The primary goal was to find methods for

comparing landscape locations between the three

countries. The second goal is to identify significant

differences in the organization of religious elements

in the landscape, and to discuss and possibly explain

them in relation to the religious and political development

of the three countries.

The farm was the hub around which the social,

economic, and spiritual life in the Norse world revolved.

In search of Norse cultic landscapes, pagan

or Christian, it is natural to focus on the location of

the farms, farm cores, pagan graves, and churches.

The sites in the three countries were selected

from the Sunnfjord region in Sogn og Fjordane in

West Norway, the Mývatn and Skagafjörður regions

in Northern Iceland, and the so-called Eastern

Settlement and Western Settlement in South West

Greenland (Fig. 1). All the sites in West Norway

and Iceland were visited in the field. Most of the

Greenland sites have been visited earlier; all were

analyzed on the basis of published archaeological

maps (in Krogh 1982 and in Guldager et al. 2002).

Two methods were used to make the comparisons:

an attribute analysis where the sites (graves and

churches) were classified according to their proximity

to certain landscape variables or attributes, and

a distance analysis where the distances between the

sites and the farm cores were measured.

The analysis shows that in West Norway there

was continuity in the use of the landscape from pagan

to Christian times. In Iceland, the pagan burials

are located according to different principles than

the burials in West Norway, and there appears to be

a break in continuity from pagan to Christian times.

No pagan burials have yet been found in Greenland.

The early churches in Iceland lie completely integrated

among the farm houses (see Krogh 1983).

This pattern seems to be the case also for some of

the West Norwegian churches. Other Norwegian

churches, however, are located in what appears to be

more publicly accessible areas away from the farm

houses. These church sites differ dramatically from

the Icelandic church sites, and are believed to reflect

a new principle for church building in the Norwegian

Middle Ages.

Greenland’s church locations appear to be a combination

of the Icelandic and the Norwegian location

types, showing affinity both to Icelandic and Norwegian

church-building traditions.

Visual Landscape Analysis

The field-work behind this study was initially

based on the principles of visual landscape archaeological

methods as they were presented in 1997

(Gansum et al 1997). The methods launched back

then were modifications of a landscape architectural

approach (as in Lynch 1992), but adapted to serve as

landscape archaeological tools.

The principle of a visual landscape analysis is to

describe how the various elements in the landscape

are located relative to each other (what may be seen

from where, which sites are visually dominant, and

which seem more isolated or remote). In an archaeological

context, it is also important to know what

constructions were contemporary and what function

they had, as well as the relative age of the various

installations in the landscape.

For this paper, only a selection of the data collected

during the field-work was used. This paper

focuses on spatial organization and layout, and especially

the proximity between various features in

the landscape, and also how various topographical

elements have been used.

Farms

The Norse population lived at farms. Farms are

places, and most events recorded in the medieval

written records are associated with specific farms.

The farm core1, i.e., the cluster of houses in each

farm unit, was the principal social arena in Norse society.

In the present analysis, the ancient farm cores

have been tentatively reconstructed using archaeological

and/or retrospective historical methods.

The historic farm cores sometimes had almost

village-like properties; often they also consisted of

several holdings2. The West-Norwegian “klyngetun”

(clustered farm / historical farm) was perhaps

the closest to a village in appearance (e.g., Berg

1968:87–210). Here, sites of the historical farm core

are supposed to go back to at least the Middle Ages,

perhaps even further. Archaeologically, farm cores

from the Early Iron Age have frequently been discovered

on present-day farm lands. Farm cores from

the Late Iron Age are, on the other hand, rarely found

and therefore are assumed to lie in the same place as

the historical farm core. Recent archaeological investigations

in West Norway have also confirmed this

interpretation, both directly and indirectly. In fact the

investigated farm cores go back to at least Pre-Roman

times (Dokset 2007, Olsen 2010, Øye 2002:69).

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, a

land reform was launched in Norway to assemble

the many small lots of land into larger, more viable

units, and new, single-farm cores where built.

Detailed farm maps describing the situation before

the land-reform and specifying the location of the

old farm lots, farm cores, boundaries, home fields,

roads, and landing places were used as important

source material for this analysis.

Viking Period burials in Trøndelag3 may be associated

with prehistoric farms (Sognnes 1988:15),

but not all the prehistoric farms have archaeologi2010

B. Gjerland and C. Keller 163

cally visible graves. In other regions, the farm-grave

relationships are not that simple; many farms have

more than one Iron Age cemetery, and others have

none. Studies indicate that Late Iron Age graves

may represent independent (i.e., inheritable) farms

(Iversen 2004:66–71). A farm without graves may,

on the other hand, indicate a tenant farm. It should

be remembered that most people in the pre-Christian

era did not get an archaeologically visible burial.

In the attribute analysis in Table 1 and Figure

2, the reconstructions of farm cores contemporary

with the Viking Age graves in West Norway were

based on the land-reform maps from the end of the

nineteenth century. In Iceland and Greenland, the

contemporary farm cores were identified archaeologically.

The home fields were identified either

on the basis of land-reform maps (Norway), or on

home-field boundary walls (Iceland), or on the improved

fields next to the farm cores (Greenland).

Pagan Burials

Burial customs in Viking Scandinavia were extremely

diverse (Gräslund and Müller-Wille 1993).

In Norway alone, some 6000 graves from the Viking

Period are known (Solberg 2000:222), some with

horses and boats (Müller-Wille 1970). Both cremation

and inhumation burials were used in Scandinavia,

but cremations decline towards the south and

west; they are less common in Denmark, rare in

the Norse cemeteries in the British Isles, and nonexistent

in Iceland (Graham-Campbell and Batey

1998:144; but see Friðriksson in Eldjárn 2000:594,

Richards 2003:391).

Graves in Norway are normally marked by a

mound or cairn, usually in an easily visible spot—

located near the farm core or within sight of it, by

the farm road, or sometimes by the boat-house or

-landing (Solberg 2000:222). There are also Viking

Period graves under flat ground, often with a modest

Figure 2. Radar diagram showing landscape attributes connected to burial sites in West Norway and Iceland. For comparison,

burials from West Norway dated to Early Iron Age and the General Iron Age are indicated. Eight attributes are indicated

clockwise around the diagram; they are not mutually exclusive, i.e., one burial site may feature one attribute, another two

or three attributes.

Table 1. Landscape attributes connected to burial sites in West Norway and Iceland. For comparison, burials from West

Norway dated to Early Iron Age and the General Iron Age are included.

Attributes

Area Farm core Home field Route Post-box Boundary Water Beach Welcome

Raw data

Early + General Iron Age in West Norway 8 11 8 3 1 10 8 5

Late Iron Age in West Norway 8 8 0 1 0 5 5 7

Iceland 0 0 8 3 6 7 7 7

Normalized data

Early + General Iron Age in West Norway 14.8 20.4 14.8 5.6 1.9 18.5 14.8 9.3

Late Iron Age in West Norway 23.5 23.5 0.0 2.9 0.0 14.7 14.7 20.6

Iceland 0.0 0.0 21.1 7.9 15.8 18.4 18.4 18.4

164 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

stone paving.

In terms of the grave furniture, the roughly 350

graves discovered in Iceland may be associated with

the lower to medium range of Norwegian graves in

terms of status. The burials in Iceland are often located

by a track, but often also near a boundary, or facing

a lake, river, or the sea. Most of them lie under flat

ground with little or no preserved surface marking;

many have horses and some have boats (Friðriksson

in Eldjárn 2000:592–593, 610; Friðriksson 2004).

They are notoriously difficult to find.

The Icelandic graves may have much in common

with the North Norwegian graves from the

Merovingian period (560/570–800 A.D.; see Solberg

2000:182–184, 186–188). These are usually inhumation

graves and often under flat ground, and the

frequency of horses in the burials increases into the

Viking Period.

Norse Greenland was, according to the written

records, settled around A.D. 985. The Saga of Eirik

the Red (Eiríks saga rauða) claims Eiríkr was a pagan

on arrival in Greenland, and credits his son Leifr

with the introduction of Christianity. The credibility

of the story has been questioned (e.g., Krogh 1975).

No unequivocal pagan Norse burials have yet been

found in Greenland, but considering how difficult

it is to find pagan graves in Iceland, the question of

pagan burials in Greenland must remain open.

The burial customs of the Norse changed dramatically

with the introduction of Christianity in the

tenth to eleventh centuries; all Christians were entitled

to burial in consecrated ground. In Scandinavia,

Iceland, and Greenland, the dead were inhumed

in cemeteries which, like in the British Isles, were

established around the churches. Most medieval

churches in the Northern world were built at farms,

and most of the churches and their parishes still carry

their original farm names (Olsen 1928:234–255).

Pagan Burials: Attribute Analysis

Ten burial sites in Sunnfjord4 in West Norway

were selected for comparison with burial sites in

Iceland. Previous analyses of these and other sites

in the Sunnfjord region were performed by Gjerland

in Sigurðsson et al. 2005. The burials were dated to:

1. Early Iron Age (ca. 500 B.C.–A.D. 560/570), 2.

Late Iron Age (A.D. 560/570–1050), and 3. Iron Age

General (500 B.C.–A.D. 1050; these are burials that

belong to either the Early or Late Iron Age, but either

the artifacts did not allow a more specific dating, or

the cairns have not been archaeologically examined).

The attributes selected are (clockwise from top

of Fig. 2): Farm core = location among or nearby the

houses on a farm; Home field = location at the home

field;Route = location at or addressing a major route

or track, i.e., between farms or settlements; Post-box

= location at or addressing the track from a major

road to the farm core; Boundary = location at or addressing

a farm boundary on land; Water = location

overlooking or addressing either the sea, a lake, or a

river; Beach = location at a beach (will often address

water); and Welcome = location at or addressing the

track leading from a boat-landing5 to the farm core.

For comparison between West Norway and

Iceland, only graves from the Late Iron Age are

relevant, but in order to discuss continuity within

West Norway, graves from the earlier periods were

included in the analysis.

The burials are single, or in small grave fields.

Most of the graves do not exist in the landscape

today, but the material and locations are recorded in

the archaeological archives.

From Iceland, burial sites from ten farms in the

Skagafjörður and Mývatn regions were selected for

visual analysis. Site locations and archive information

were kindly provided by Guðný Zoëga, Adolf

Friðriksson, and Árni Einarsson.

The number of analyzed localities is modest, and

the results should therefore be treated with caution.

Based on our general archaeological knowledge,

however, it is likely that the attributes will prove to

be significant also in larger regional studies.

The actual material information is presented as

raw data and is given in the tables. The presentation

in the radar diagrams show normalized data and thus

give a relative value of the different attributes compared

to each other within each area. The normalized

data must, however, be used with caution due to the

limited number of analyzed objects.

The West Norwegian graves in this material are

located close to the farm cores, and they are also on

the home fields. This relationship seems consistent

throughout the Iron Age. This aspect of the West

Norwegian graves marks a distinct disparity with

the Icelandic graves in this material, which never

lie close to farm cores or on the home-fields (the

distance between farm cores and graves is addressed

in the section on distance analysis below). In contrast

to the West Norwegian graves, all the Icelandic

graves in the material are situated near routes, and

most of them are also near farm boundaries. This

situation is rare in the West Norwegian Iron Age material,

and almost non-existent in the Late Iron Age.

There are two sets of attributes that appear to

complement each other, which should be discussed

together. The first set consists of graves on a beach,

and/or overlooking water, and/or in a welcoming

position, i.e., on the track between the boat-landing

and the farm core. In West Norway, these locations

are common both for Late Iron Age graves and for

Iron Age graves in general. The attributes all have

to do with water in some form or other. It is tempting

to suggest that they indicate travel by boat or on

ice. The second set consists of graves overlooking

a route, and in post-box positions, i.e., on the track

leading from a main route to the farm core. This

situation is typical for Iceland, but these locations

2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 165

are rare in the West Norwegian material. These attributes

also have to do with travel, only this time on

land, i.e., on foot or on horse-back.

Travel on fjords and on lakes is traditional in

West Norway, while travel on foot or on horseback

is traditional in Iceland. Still, quite a few burial sites

have a marine orientation. It is possible that the two

groups of attributes represent similar connotations,

only adapted to the local conditions for travel.

Pagan Burials: Distance Analysis

It was pointed out that the Iron Age burials in

West Norway were situated closer to the farm cores

than the Icelandic burials in this analysis. The West

Norwegian graves have an affinity to farm cores and

home fields, while the Icelandic graves have an affinity to farm boundaries and routes some distance

away from the farm cores.

For a proper comparison, the distances between

graves and farm cores need to be specified (Table 2,

Fig. 3). This study shows that the West Norwegian

graves range from 70 to 700 m from the farm cores,

but the main body of the material lies within a medium

range of 100 to 300 m.

By comparison, the Icelandic burial sites range

from 300 to an impressive 1750 m, with the main

body of the material in the range of 500 to 1200 m

from the farm cores. Based on general knowledge of

Icelandic burials, these examples may tilt towards

the extreme, but distances in the vicinity of 500 m

seem to be quite common (see Maher 2009 for extensive

studies of graves and locations in Iceland).

The general observation that there is a difference

in the location of the pagan burials between West

Norway and Iceland seems to be largely confirmed

by the distance analysis, although caution must be

urged due to the limited sample size.

Pagan Burials: Discussion

The differences between the West Norwegian

and the Icelandic burial locations may be addressed

in several ways. To what extent did the

landscape of the dead resemble the landscape of

the living? The attribute analysis suggests that

in West Norway, burials from both the Early and

Late Iron Age often were located near the farm

core, i.e., close to where people lived, and close

to the social arena. It is equally significant that the

graves were situated at or in the direct vicinity of

the home field.

The farming economy of West Norway was a

mixed economy; cereal cultivation was combined

Figure 3. Distance between burial sites and farm cores in samples from Iceland and West Norway.

Table 2. Distance between burial sites and farm cores in samples from Iceland and West Norway.

Area Distance (m)

West Norway 70 75 100 140 140 230 280 340 350 400 400 500 750 800

Iceland 300 500 500 500 500 1100 1240 1400 1750

166 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Icelandic culture for centuries (Adolf Friðriksson in

Eldjárn 2000:610).

Graham-Campbell and Batey (1998:145) observed

that in Scandinavian Scotland the dead

were often “… removed some distance from the

living for burial …”, i.e., similar to the pattern in

Iceland. They also noted (1998:145–156) that there

was “a marked tendency in Scandinavian Scotland

to utilize pre-existing mounds, thus ensuring the

identification of the burial place in the landscape.”

Using other peoples’ cemeteries may be a way of

demonstrating power, but it may also be pure convenience

(see Barrett 2003, Geake 2003, Meaney

2003, Richards 2003 for overview of Norse burial

customs in Britain. Ambrosiani 1998 for Ireland,

Andersson 2005 and Welinder 2003 for Sweden). In

addition, there were Norse graves facing the sea, or

lakes, which apparently is quite common in the rest

of the Norse Atlantic area (Graham-Campbell and

Batey 1998:145).

The Christianization of Norway and Iceland

Scandinavians visiting the Continent or the British

Isles prior to the Viking Age would have encountered

Christians and Christianity in many forms and

places. The most likely contact areas were Germany6,

Anglo-Saxon England7, Ireland, and Frisia8 (Sawyer,

B. 1987; Sawyer, P.1987; Sawyer et al. 1987).

The thirteenth-century Icelandic chronicler Snorri

Sturlusson (Sturlusson et al. 1987) described the

Christianization of Norway. Playing down the German

influence as illustrated by Rimbert (Robinson

1921) and Adam of Bremen (Bremensis et al. 2002),

he called attention to the Christianization efforts of

Norway’s three missionary kings: Hákon Haraldsson

“the good”9 (A.D. 933–959), Óláfr Tryggvason

(A.D. 994–999), and Óláfr Haraldsson “the saint”

(A.D. 1015–1028).

Norwegian historians have traditionally embraced

the Anglo-Saxon Church as “the mother of

the Norwegian Church”10, in line with Sturlusson’s

description (Keyser 1856–58; Maurer 1855–56,

1895; and especially Taranger 1890; see Myking

2001 for historiography; also Bang 1887, 1912;

Birkeli 1982; Brendalsmo 2001; Bull 1912; Helle

1995a, b; Jackson 1994; Koht 1921; Kolsrud 1958;

Kragh 1995; Lönroth 1963; Løwe 1995; Sigurðsson

2003a:29; Sveaas Andersen 1995).

The charismatic kingships that appeared during

the Viking Period developed to a medieval statelike

structure under King Hákon Hákonarson (A.D.

1217–1263). The Gregorian Church Reform11 was

launched in Europe in the eleventh century to disengage

the Church from the power of secular leaders.

Prior to the reform, most churches in Northern

Europe were privately built and owned, either by the

community, the nobility, or the kings. This was also

the situation in Scandinavia.

with animal husbandry and supplemented with

hunting and fishing. Most indigenous religions

in farming communities somehow involve ancestors,

fertility, and productivity (Dumézil 1977;

Steinsland 2005:77–81, 144–164). It makes sense,

therefore, that so many of the West Norwegian

graves are located on or are addressing arable land.

It is tempting to interpret this close-to-home location

as related to ancestral worship (see Steinsland

2005:327–357).

Still, it is interesting that many of the graves

in West Norway and Iceland seem to relate to the

topic of travel, either because the burial location is

facing the sea, or because the dead was buried in a

boat (Müller-Wille 1970, Solberg 2000:263, Westerdahl

1991). Adolf Friðriksson wrote (in Eldjárn

2000:591–592) that graves in Iceland were usually

associated with a farm, but he continued: “In contrast

to the Christian graveyards, pagan burials were

not situated by the farmhouses or even within the

boundaries of the home field, but on the nearest suitable

ground outside the hayfields; on a low rise or

bank, perhaps half a kilometer or so away from the

farmhouse.” He has also stated that in some cases

graves were located near the boundaries between

properties, and in other cases beside a road or a track

(loc. cit. and Friðriksson 2004).

Torun Zachrisson speaks of rune-stones marking

boundaries in eleventh-century Sweden (Zachrisson

1998:194–196), and refers to the Irish practice of

burials with ogam inscriptions marking boundaries

(in Charles-Edwards 1976:85). The attribute analysis

in Figure 2 supports such relationships. In addition,

the comparison with West Norway points to the fact

that there is an almost negative correlation between

Icelandic burials, and farm cores and home fields.

The colonization or “landnám” situation in Iceland

may have required a different burial practice

simply for legal reasons. When the first settlers

arrived in Iceland around A.D. 874, there were no

ancestors buried on the land, and hence no graves to

worship. The Italian archaeologist Elena Garcea has

stated (in a completely different context) that “by infusing

the land with the remains of your people, you

claim it” (quoted in Gwin 2008:137). It is possible

that the graves of the early settlers in Iceland might

have served as territorial claims.

It is interesting that the graves both in Iceland

and West Norway have an affinity to the subject of

travel, either routes on land or water. This commonality

may indicate a connection between Scandinavian

and Icelandic burial customs, but Scandinavia

is not the only possible source of influence; at the

time of the colonization of Iceland, around A.D. 874,

there were several Norse kingdoms in the British

Isles (see Forte et al. 2005 for details). These Anglo-

Saxon-Norse hybrid societies clearly influenced

2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 167

copal seat was established at Garðar in the Eastern

Settlement (Keller 1991; Seaver 1996:33, 64–65).

Church Building

The contrasts between Norwegian and Icelandic

medieval churches were striking. The oldest Norwegian

churches were corner-post constructions in

wood with standing “staves” (vertical timbers) dug

into the ground. Post-holes from more than 30 such

churches have been excavated under the floors of

standing churches.

Norway is famous for its stave-churches, which

probably numbered some 750 by the end of the Middle

Ages; today only about 60 remain. Their construction

resembles that of the corner-post churches,

but the vertical timbers all rest upon a frame of

wooden sills laid out on the ground. So in contrast

to the stone churches and the turf churches, stave

churches leave no post-holes in the ground. Hence

these church sites are difficult to identify archaeologically.

(Christie 1981, 1983; KLNM Vol. 17:95–

107 “Stavkirke” [compare to KLNM Vol. 17:84–95

“Stavbygning”]—available online at http://www.

stavkirke.org and http://www.stavechurch.org, respectively).

The ca. 150 Norwegian stone churches that are

still standing were built after ca A.D. 1100, most

of them probably by foreign masons, and few if

any stone churches were built after the Black Death

A.D. 1349 (Ekroll 1997, Ekroll et al. 2000, Lidén

1991; see also Lidén 2008 [http://kunsthistorie.com/

wiki/index.php/portal:steinkirke]). It is virtually unknown

that North Norway also had a number of turf

churches. None are standing today, and very little is

known about these churches, their construction, and

dating (Bratrein 1968).

In Iceland, there are written records about ca.

320 parish churches in the Middle Ages. In addition,

there were numerous small churches that did not employ

a priest (Vésteinsson 2000:93, 295–296). Many

of these retained burial rights up towards the High

Middle Ages.

There are no standing churches from the Middle

Ages in Iceland, but both wood- and turf-churches

are known from the written records, and several turf

churches have been excavated (KLNM Vol. 17:101–

104, Vol. 7:121–122; Kristjánsdóttir 2004:45–50,

119–149; Vésteinsson 2000:93–143). The Icelandic

turf churches were basically timber buildings (both

corner-post and stave-constructions have been excavated)

with outer protective walls of turf and stone.

The gable ends were made of wood, or at least the

western gable which held the entrance. Turf houses

require high maintenance and are not long-lasting.

Contrary to Norway and Greenland, there are no

medieval stone churches in Iceland.

With the establishment of a Norwegian Church

Province in Niðarós (present-day Trondheim) in

A.D 1152–53, a true North Atlantic archbishopric

was set up12 (Imsen 2003). The foundation document

Canones Nidarosiensis established that the Gregorian

Reform be implemented in the new church province

(Bagge 2003:55–61, 80). With this reform, the

proprietary church system in Norway was brought to

an end, and private churches were transferred to the

Church. This transfer included the many churches

that belonged to the King. The intention was to apply

the Gregorian Reform throughout the Niðarós

Province, but after King Sverrir’s (A.D. 1177–1202)

fall-out with the Church during the Norwegian Civil

Wars, the reform was impeded. It was never implemented

to the full in Iceland and Greenland.

There were Christians among the early immigrants

to Iceland, and missionaries also came from

abroad. Iceland was ruled by chieftains who met

at the National Assembly “Alþingi” and ruled by

a common law. There was no central authority; the

political power rested with the chieftains.

During pagan times, the goðar were cult leaders

(Lucas and McGovern 2007; see also Lucas 2009).

When the question of Conversion to Christianity

was put before the National Assembly ca A.D. 1000

(Aðalsteinsson 1971, Kristjánsdóttir 2004:142–152,

Vésteinsson 2000:17–37), the goðar changed their

religion, but maintained their influence on religious

affairs. They resented intervention from the central

clerical authorities, and the tension probably increased

when Iceland and Greenland became parts

of the Niðarós Church Province A.D. 1152–53.

Bishops appointed by the Icelanders themselves sat

in office until 1237, but the right to appoint bishops

rested with the chapter in Niðarós from A.D. 1238

until the reformation 1536.

Throughout Iceland, churches had been erected

on private farms. As elsewhere, farmers donated

property to the churches, and gradually two types

of churches emerged: the “staðir” churches had full

ownership of the farm at which they were located,

and were financially attractive. The rest were called

bændakirkjur (peasant churches). The struggle between

the Church and the goðar in the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries to control the “staðir-churches”

is known as “staðamál” (Sigurðsson 2003b:122–124,

Stefánsson 1995, Vésteinsson 2000:90–91).

When Iceland and Greenland became parts of the

Norwegian kingdom from A.D. 1262–64, the time

of chiefly rule was brought to an end. However, as

mentioned above, the Gregorian reform was never

properly implemented in Iceland. Hence the proprietary

church system prevailed until the reformation.

Greenland was allegedly pagan for the first few

years, but converted to Christianity around the same

time as the Icelanders. Their first bishop, Arnald,

was consecrated in Lund A.D. 1124, and the Epis168

Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Greenland’s churches appear to be a mixture

of Icelandic and Norwegian (or at least European)

traditions. Unlike Iceland, Greenland had several

European-style stone churches, particularly

the near-intact Hvalsey Church in Qaqortukulooq

built shortly after A.D. 1300 (Krogh 1982), which

has been suggested to be very similar to Norwegian

churches (Roussell 1941). The smaller churches,

including the so-called Þjóðhild’s church at Brattahlið/

Qassiarsuk (Krogh 1982:27–52, Krogh 1983)

appear to be in the same tradition as the Icelandic

turf churches.

Churches: Attribute Analysis

A traveler to the Norwegian countryside will

notice the white churches perched majestically on

top of hills overlooking the farms below or standing

proudly on the beaches along the west coast supervising

the traffic on the fjords. Going to Iceland,

the same traveler will be surprised to find rural

churches nested neatly among the farm houses, not

at all in such ostentatious locations as the Norwegian

churches. Why this difference in church location

between Norway and Iceland? Does it mean

anything? The visual impact is striking, but can

the difference be documented, and how? To have

a closer look at how the churches are actually located,

it is natural to start with an attribute analysis

similar to the one made for the burials (Table 3,

Fig. 4). To facilitate comparisons, the same eight

attributes that were used in the burial analysis are

utilized once more.

In West Norway, 15 medieval church-sites in the

Sunnfjord region were selected and visited for analysis—

the same region and some of the same farms that

Table 3. Landscape attributes connected to medieval church sites in West Norway, Iceland, and the Eastern Setlement and the

Western Settlement in Norse Greenland.

Attributes

Area Farm core Home field Route Post-box Boundary Water Beach Welcome

Raw data

West Norway 5 12 12 0 2 13 8 1

Iceland 10 10 5 4 0 2 0 0

Greenland 13 13 5 3 0 12 6 7

Normalized data

West Norway 9.4 22.6 22.6 0.0 3.8 24.5 15.1 1.9

Iceland 32.3 32.3 16.1 12.9 0.0 6.5 0.0 0.0

Greenland 22.0 22.0 8.5 5.1 0.0 20.3 10.2 11.9

Figure 4. Radar diagram showing landscape attributes connected to medieval church sites in West Norway, Iceland, and the

Eastern Settlement and the Western Settlement in Norse Greenland. Eight attributes are indicated around the diagram. They

are not mutually exclusive, i.e., one church site may feature one attribute, another two or three attributes.

2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 169

The church locations in these samples are strikingly

different. The West Norwegian churches in

the sample have an almost bimodal distribution, or a

slanted figure of eight, in the graph (Fig. 4). Up and

to the right are the attributes farm core, home field,

and route. The churches with these attributes belong

to what is called “Phase 1”, which will receive special

attention in the discussion below. Down and to the left

is another group of church sites that belongs to what is

called “Phase 2”, which also is discussed below.

The Icelandic churches in the sample have an

overwhelming affinity to farm core and home field,

similar to the Norwegian “Phase 1” churches. There

is also some affinity to route and post-box locations.

The Greenlandic churches in the sample have a

great affinity to water and welcome positions. This

is hardly surprising, given the fact that most Norse

farms in Greenland are located near the shore, much

more so than in West Norway, where there are also

many inland farms. The Greenland churches also

have a strong affinity to farm cores and home field,

just like the medieval churches in Iceland.

Churches: Distance Analysis

Can the various church location types be better

understood if their distances from the farm cores

were visited during the pagan burial analysis. There

are no longer medieval churches at these sites; most

have early modern churches where the medieval

churches once stood, and some have no church at

all. The medieval churches in this district are all

mentioned in the cadastre “Bergen Kalvskinn”13,

and most of the medieval churchyards are still in use

(Riksantikvaren14), although the buildings are more

recent. Abandoned medieval church-sites have also

been identified (Buckholm 1998).

In Iceland, 10 medieval church sites were selected

and visited for analysis, most of them in the

Skagafjörður region in cooperation with Guðný

Zoëga. The exception was the Hofstaðir site in

the Mývatn region (Hofstaðir reports [http://www.

instarch.is/instarch/midlun/netverkefni/arena/gogn/

hofstadir/]). The churches and dwellings are all

identified archaeologically.

In Norse Greenland, 13 church sites in the Eastern

and in the Western Settlement were selected

for analysis, the total being at least 18. None were

visited for this analysis, but most of them are well

known to one of the authors, and high-resolution

documentation is easily available (Guldager et al.

2002, Krogh 1982). Churches and dwellings are

identified archaeologically.

Table 4. Distance between church and farm core in samples from West Norway, Greenland, and Iceland.

Area Distance (m)

Iceland 10 15 15 17 25 26 26 30 30 30

Greenland 0 5 15 20 25 30 30 35 40 45 50 80 140

West Norway 30 60 70 70 70 100 140 150 190 230 230 230 250 380 530

Figure 5. Distance between church and farm core in samples from West Norway, Greenland, and Iceland. In the Norwegian

material, the dark blue bars are “Phase 1” churches, the rest are “Phase 2” churches.

170 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

to 530 m. This arrangement probably has some very

specific reasons which will be addressed below. The

Norse Greenlandic churches are located between 0

and 140 m from the dwellings, i.e., in positions that

place them between the Icelandic and the West Norwegian

churches in the sample. Part of the reason

may be that the houses on Norse farms in Greenland

appear to be more dispersed than in Iceland.

Churches: Discussion

Both in the attribute analysis and in the distance

analysis, the Icelandic churches stand out as being

integrated among the farm houses. This relationship

is characteristic for Icelandic churches even today.

In the Middle Ages, the churches were surrounded

by a churchyard, normally circular in shape. For the

Icelanders, the construction of a cemetery among the

farm houses implied a discontinuity in their burial

customs: the furnished pagan graves some distance

away from the farm core were replaced by a churchyard

next door to the living (Table 5, Fig. 6).

are measured? Table 4 and Figure 5 present the

data and graphical representation of the distance in

meters between medieval churches and their contemporary

parent farms in West Norway, Iceland,

and Greenland.

In West Norway, the distance from the church

is measured from the chancel to the center of the

historical farm cores in land-reform maps. In Iceland,

the distance is measured from the center of the

church site, which is normally very small, to the center

of either the (medieval?) dwelling or the center

of the farm-mound. These locations are all based on

archaeological finds such as house-ruins and observation

of human bones indicating the church-yard.

In Greenland, the distance is measured from the wall

of the church ruin to the nearest wall of the dwelling,

on the basis of survey maps. All the identifications in

Greenland are based on archaeological recognition

of the ruins.

The Icelandic churches are characterized by

lying close to the dwellings, in the range of 10 to

30 m. The Norwegian churches are located both

nearby and far from the farm cores, ranging from 30

Table 5. Attribute analysis with location of pagan graves compared to medieval churches in the samples from Iceland.

Attributes

Material Farm core Home field Route Post-box Boundary Water Beach Welcome

Raw data

Pagan graves 0 0 8 3 6 7 7 7

Churches 10 10 5 4 0 2 0 0

Normalized data

Pagan graves 0.0 0.0 21.1 7.9 15.8 18.4 18.4 18.4

Churches 32.3 32.3 16.1 12.9 0.0 6.5 0.0 0.0

Figure 6. Attribute analysis with location of pagan graves compared to medieval churches in the samples from Iceland.

2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 171

It is a likely assumption that the location of

Icelandic churches reflects the proprietary church

system, i.e., that the churches were originally privately

built and owned. The most astonishing part

is not that the early churches were built like this,

but the fact that the tradition has prevailed until

modern times.

The West Norwegian church locations stand out

(Table 6, Fig. 7). During the field survey, it was

discovered that some of the churches were located

almost like the churches in Iceland, i.e., close to

home field and farm core, by a road, in what looked

like private locations. These churches are tentatively

labeled “Phase 1” churches. In the attributes analysis

in Figure 4, the “Phase 1” churches are indicated top

right; in the distance analysis in Figure 5, they are

indicated by dark blue bars.

The Norwegian churches are surrounded by

modern church-yards which have expanded with

the population; hence, they are most likely larger

than in medieval times. This growth may explain the

slightly greater distance in the Norwegian material

between the “Phase 1” churches and the houses. In

addition, the distance is measured to the center of

the historical farm core as indicated by the historic

maps. In both Iceland and Greenland, the distances

are based on the archaeological material.

The most striking church locations are the ones

where the churches are located far from their parent

farms. During the field survey, it was observed that

many churches were lying by themselves, often at a

beach or near a river, overlooking water. Some were

placed on gravel estuaries15 in places convenient for

boat landings. These church locations seem to be

rather public in nature. Such churches are labeled

“Phase 2” churches.

In the distance analysis, there is no obvious gap

to indicate the difference between the “Phase 1” and

Table 6. Attributes analysis with graves and churches in the samples from West Norway. The location of Late Iron Age

graves compared to the location of medieval church sites.

Attributes

Material Farm core Home field Route Post-box Boundary Water Beach Welcome

Raw data

Late Iron Age graves 8 8 0 1 0 5 5 7

Rest of Iron Age graves 8 11 8 3 1 10 8 5

Churches 7 12 12 0 2 13 8 1

Normalized data

Late Iron Age graves 23.5 23.5 0.0 2.9 0.0 14.7 14.7 20.6

Rest of Iron Age graves 14.8 20.4 14.8 5.6 1.9 18.5 14.8 9.3

Churches 12.7 21.8 21.8 0.0 3.6 23.6 14.5 1.8

Figure 7. Attributes analysis with graves and churches in the samples from West Norway. The location of Late Iron Age

graves compared to the location of medieval church sites. For background, graves from the rest of the Iron Age are included.

172 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

“Phase 2” churches. The distance of 80 m between

church and farm core has been used to distinguish

between “Phase 1” and “Phase 2” West Norwegian

churches, i.e., the “Phase 2” churches lie more than

80 m away from the farm core. This definition is also

based on visual impression; the topography and the

visual scale of the landscapes are important factors

in such analyses.

River estuaries served in the past as convenient

places to load and unload cargo between boat and

overland transport. Thus, estuaries became nodes in

the communication systems along the coast. Bronze

Age and Iron Age finds indicate that farms near

the estuaries often became power-centers which

controlled exchange networks in larger regions

(Farbregd 1986). Middle Age towns were usually

placed at waterways, and river estuaries were

popular locations: both medieval Oslo and medieval

Niðarós (Trondheim) were established at estuaries.

Maybe the Phase 2 churches were not only meant

to facilitate public access, but were built at strategic

locations to serve as nodes in larger communication

networks. Through the Middle Ages, the Roman

Catholic Church developed into a well-organized,

hierarchic administrative system for which communication

was essential.

The “Phase 1” and “Phase 2” churches may reflect different stages in the organizational development

of the Church of Norway. “Phase 1” churches

close to the farm core can easily be interpreted as

private churches, also implying chronological differences

where these churches could be oldest. The

“Phase 2” churches may indicate public churchbuilding,

whether the builder was a congregation,

the Church, or the King. It is tempting to suggest that

these churches may have been built after the ideas of

the Gregorian reform had started to take hold. The

churches could then belong to the second generation

of medieval churches in West Norway, built in the

twelfth century (see Lidén 1995:140).

At the moment, it is difficult to talk about possible

structural differences between the two phases.

An analysis of the churches mentioned in the “Bergen

Kalvskinn” cadastre indicates that in the first half of

the fourteenth century the majority of these churches

were parish churches (Tryti 1987:434–435). All the

churches except one were stave churches, with the

exception being a “Phase 1” stone church at Lunde

in Gaular. Only four of the “Phase 2” churches were

not parish churches.

It is interesting that the Norse Greenland church

locations end up in between the Icelandic and the

West Norwegian churches, both in the attribute

analysis and in the distance analysis. Similarly, the

Greenland church buildings point in two directions:

there are turf churches with circular churchyards like

in Iceland, and there are stone churches with rectangular

churchyards like in Norway and the rest of

Europe. The late stone-churches in such high-status

farms as Brattahlíð/Qassiarsuk, Hvalsey/Qaqortoqulooq,

and Herjólfsnes/Ikigaat in the Eastern Settlement

and Ánavík and Sandnes/Kilaarsarfik in the

Western Settlement are all “Phase 2” churches facing

public (?) boat-landings. However, the Cathedral

at Garðar/Igaliku and the churches at Ketilsfjörðr/

Tasermiutsiaat and Uunatoq are integrated “Phase 1”

churches in accordance with the “Icelandic” pattern,

despite their size.

It is worth recalling that all bishops in Iceland

were Icelanders prior to A.D. 1238, while all the

bishops in Greenland16 throughout the Middle Ages

were Norwegians (see Seaver 1996).

By the looks of it, the European-style stone

churches may reflect a Norwegian influence on

church building in Greenland. This may have several

reasons, but it is relevant to ask whether Greenland

ever experienced a struggle among the chiefs to control

the churches, like the staðamál conflict among

the goðar in Iceland. It is tempting to suggest that the

Greenland Church developed along trajectories that

were different from those of the Icelandic Church.

Visual Landscape Analysis and Source Material

The landscape analyses in this paper had a focus

on finding methods to compare three very different

landscapes in West Norway, Iceland, and Greenland.

It set out with a range of observations and documentations.

The landscape variables utilized in the end

were selected because they revealed features characteristic

for the sites. The attributes may well reflect

the typical archaeological perception of sites in each

of the landscapes. When this perception, however, is

formalized, like in the eight attributes applied here,

the ground for comparisons between different landscapes

is laid.

The attribute analyses needed to be backed up by

measurements of distances between farm cores and

graves, and between farm cores and churches. This

gives a better understanding than indistinct statements

of the type “the church lies close to the farm”.

Within the realm of one landscape, such descriptive

statements have their uses, but in a comparison

between different landscapes, more precise information

is needed.

The analyses exposed the challenges that arise

when archaeological and historical information

from different countries is used in the same study.

The diversity in the source material made it possible

to identify, for example, Viking and medieval farm

cores in the field, but due to the diverse nature of the

source material, different criteria had to be applied in

each sample area. In the present case, farm clusters

were identified on the basis of the historical farms in

2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 173

in distinctly public places such as river estuaries

and open beaches, i.e., traditional landing places for

boats and cargo and clearly also social arenas, which

may go way back in time. Tentatively, the West Norwegian

churches in the sample have been classified

as “Phase 1” and “Phase 2” churches. The “Phase

1” churches lie in locations similar to the Icelandic

churches (which are all “Phase 1”) in that they are

integrated in a house cluster, while the more public

“Phase 2” churches are unknown in Iceland. Interestingly,

Greenland has both “Phase 1” and “Phase 2”

churches; the “Phase 2” churches are generally larger,

later, and built in stone with angular church-yards.

The different church-building patterns may

somehow reflect differences in the legislation and/or

the church organization, but also in social conventions.

There may also be chronological differences,

but the material does not yet lend itself to detailed

chronological studies. There seems, however, to be

a shift from church-building in the private sphere

(the “Phase 1” churches) to church-building in the

public sphere (the “Phase 2” churches). As mentioned

before, it is tempting to associate the shift

with the Gregorian Church Reform and its endeavors

to abolish the proprietary church system. Norway

was a kingdom or at times several kingdoms, while

Iceland and Greenland were chiefly societies up to

AD 1262–64. The building of the public “Phase 2”

churches may also be a result of royal influence.

The question of continuity versus discontinuity

in the Norse sacred landscape cannot be given a

simple answer. In the sample area in West Norway,

the pagan graves and the “Phase 1” churches seem

to represent continuity in their close proximity to

the farm cores. The discontinuity appears with the

introduction of the “Phase 2” churches, which are

detached from the farm cores and are erected at more

public places. Hence, the cult practice is also getting

detached from the private sphere and shifted towards

public arenas.

Quite the opposite situation occurs in the sample

area in North Iceland—the pagan graves are not

associated with the house clusters, but frequently

address rather public areas such as tracks and communication

lines some distance away. These are

graves and not buildings of worship, so there is no

necessary reason to assume that their more public

locations indicate public participation in cult at the

site. The graves were meant to be seen and recognized

by travelers, although today they have no

surface markings.

The intimacy of the Icelandic churches nested

within the house clusters gives completely opposite

connotations. The private character of these “Phase

1” churches is accentuated when compared to the

public character of the “Phase 2” churches in West

Norway. Churches are cult-buildings designed for

the land-reform maps in West Norway, on the farmmounds

with identified medieval characteristics in

Iceland, and on the medieval ruins of buildings that

were abandoned sometime between the twelfth and

the fifteenth centuries in Greenland.

The analysis has triggered a need to look more

closely at the two different types of church locations,

and to analyze them in a context of visual landscape

analysis. Information available in West Norway

about farm cores, home fields, and other structures

offer unique opportunities for this sort of inquiry.

Comparative analyses are inspiring and fruitful and

will also be applied.

Continuity and Discontinuity

Was there such a thing as a sacred Norse geography

in pagan and early Christian times? The limited

regional studies in this paper indicate that there certainly

were some fairly stereotypical conventions

which were followed in each region, with a set of

variations. Caution must be observed due to the small

sample size and hence the danger of overrepresentation

of local patterns. With this warning in mind, the

following observations may give food for thought.

First of all, the pagan burials in West Norway

have a strong affinity to home field and lie close to

farm core, while the similar burials in Iceland are

located far from the farm cores. The Icelandic pagan

graves lie close to routes and farm boundaries. This

pattern appears to be fairly consistent even for a

larger body of material (see Maher 2009). Thus, it

may be fair to state that the burial customs in Iceland

follow conventions which differ somewhat from

those in West Norway. The fact that the Icelanders

were in a land-taking process may have called

for specific funerary practices to serve other needs

than the ones back home, where the properties and

settlements go way back in time. Alternatively, the

Icelandic funerary practice may reflect influence

from other communities; possibly with the Norse

communities in the British Isles.

Second, the churches in Iceland are without

exception integrated in the medieval house clusters

at the farm. This pattern must reflect the medieval

church organization in Iceland, which was completely

dominated by the proprietary church system, i.e.,

the churches were privately owned. However, the

proprietary church system alone did not necessitate

such locations, so there must have been additional,

social conventions at work.

The church locations in the West Norway sample

area stand out in clear contrast to the Icelandic pattern:

the distances between farm cores and churches

vary considerably. A few churches are integrated

among the farm cluster as in Iceland, but the majority

of the churches lie far from the farm cores, often

174 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Barrett, J.H. 2003. Christian and pagan practice during

the conversion of Viking Age Orkney and Shetland.

Pp. 207–226, In M. Carver (Ed.). The Cross Goes

North. Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe

AD 300–1300. The University of York, York Medieval

Press, York, UK.

Benediktsson, J. (Ed.) 1986. Íslendingabók (by Ári Þorgilsson).

Pp. 1–28, In Íslendingabók Landnámabók,

Íslenzk fornrit, Vol. 1. Reykjavík, Iceland.

Berg, A. 1968. Norske gardstun. Instituttet for sammenlignende

kulturforskning. Serie B, Skrifter LV. Universitetsforlaget,

Oslo, Norway.

Birkeli, F. 1982. Hva vet vi om kristningen av Norge? Utforskingen

av norsk kristendoms- og kirkehistorie fra

900- til 1200-tallet. Universitetsforlaget-Norwegian

University Press, Oslo, Norway.

Bratrein, H. 1968. Kirketuft-registreringer i Nord-Norge

1966–1968. Reports in the archives of Riksantikvaren,

Oslo, Norway.

Brendalsmo, J. 2001. Kirkebygg og kirkebyggere. Byggherrer

i Trøndelag ca. 1000–1600. Ph.D. Dissertation.

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

(NTNU), Trondheim, Norway.

Buckholm, M.B. 1998. Nedlagte kirker og kirkesteder fra

middelalderen i Hordaland og Sogn og Fjordane. Arkeologiske

avhandlinger og rapporter fra Universitetet

i Bergen, Norway.

Bull, E. 1912: Folk og kirke i middelalderen. Kristiania,

Norway.

Charles-Edwards, T.M. 1976. Boundaries in Irish law. Pp.

83–87, In P.H. Sawyer (Ed.). Medieval Settlement,

Continuity, and Change. Crane Russak, and Company,

New York, NY, USA

Christie, H. 1981. Stavkirkene – arkitektur. Pp. 139–252,

In K. Berg (Ed.). Norges Kunsthistorie Vol 1. Gyldendal,

Oslo, Norway.

Christie, H. 1983. Den første generasjonen kirker i Norge.

[With English summary]. Hikuin No. 9. Moesgård,

Højbjerg, Denmark.

Dokset, O. 2007. Gloppen kommune—reguleringsplan for

utviding av Sandane lufthamn, Hjelmeset gbnr. 54/1

og 3, Andenes gbnr. 55/7, - rapport frå arkeologisk

registrering. Rapport frå Kulturavdelinga, Sogn og

Fjordane fylkeskommune, Norway.

Dumézil, G. 1977. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. University

of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Ekroll, Ø. 1997. Med kleber og kalk. Norsk steinbygging

i mellomalderen 1050–1550. Samlagets bøker for

høgare utdanning, Oslo, Norway.

Ekroll, Ø., M. Stige, and J. Havran 2000. Middelalder i

Stein. Vol. 1. In J. Havran (Ed.). Kirker i Norge, Vol.

1. ARFO, Oslo, Norway.

Eldjárn, K. 2000. Kuml og haugfé úr heiðnum sið á Íslandi.

In A. Friðriksson (Ed.). 2nd Edition. Fornleifastofnun

Ísland, Mál og menning, Þjóðminjasafn Íslands,

Reykjavík, Iceland.

Farbregd, O. 1986. Elveosar—gamle sentra på vandring.

Spor. Fortidsnytt fra Midt-Norge. No. 2. DKNVS Museet.

Trondheim, Norway.

Forte, A., R. Oram, and F. Pedersen. 2005. Viking Empires.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Friðriksson, A. 2000. Viking Burial Practices in Iceland.

Pp. 549–610, In A. Friðriksson (Ed.). Kristján Eldjárn:

Kuml og haugfé. Úr heiðnum sið á Islandi. 2nd Edition.

Mál og Menning, Reykjavík, Iceland.

social religious activity, and the location of the

“Phase 1” churches underlines the private character

of the Christian cult in Iceland.

The present study is an attempt to address the issues

of pagan and Christian cult in the Norse cultural

landscapes. The comparative approach applied here

does give the opportunity to observe both similarities

and differences in the establishment and use of a

symbolic landscape.

Acknowledgments

The paper is based on archaeological material from

sample areas in three countries: Iceland, Greenland, and

Norway. This broad effort would not have been possible

without the cooperative attitude of numerous colleagues.

First of all we will express our thanks to Guðný Zoëga

of the Glaumbær Folk Museum and The Skagafjörður

Church Project, who has willingly shared information and

guided us in the field. Without her, this work could not

have been done. Thanks also to Bryndís Zoëga of the same

institution. Adolf Friðriksson and Garðar Guðmundsson of

the Institute of Archaeology in Iceland (FSÍ) have supplied

us with endless information about pagan burials in Iceland

over the years, and Árni Einarsson of the University of Iceland

(HÍ) and the Mývatn Research Station is constantly

finding archaeological sites everywhere; they all deserve

our gratitude. Thanks also to Ragnheiður Traustadóttir of

the Hólar University College for her cooperation and support

over many years.

Literature Cited

Bremensis, A., F.J. Tschan, and T. Reuter. 2002. History of

the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Translated with

an introduction and notes by F.J. Tschan and a new

introduction and selected bibliography by T. Reuter.

Columbia University Press, New York, NY.

Aðalsteinsson, J.H. 1971. Kristnitakan á Íslandi. Reykjavík,

Iceland.

Ambrosiani, B. 1998. Ireland and Scandavia in the Early

Viking Age: An archaeological response. Pp. 404–430,

In H.B. Clarke, M. Ní Mhaonaigh, and R.Ó. Floinn

(Eds.). Ireland and Scandinavia in the Early Viking

Age. Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ireland.

Andersson, G. 2005. Gravspråk som religiös strategi.

Valsta och Skälby i Attundaland under Vikingatid och

tidig medeltid. Riksantikvarieämbetet, Stockholm,

Sweden.

Bagge, S. 2003. Den heroiske tid – kirkereform og kirkekamp,

1153–1214. Pp. 51–80, In Imsen, S. (Ed.). Ecclesia

Nidrosiensis, 1153–1537. Søkelys på Nidaroskirkens

og Nidarosprovinsens historie. Tapir akademisk

forlag. Trondheim, Norway.

Bang, A.C. 1887. Udsigt over den norske kirkes historie

under katholicismen. Christiania, Norway.

Bang, A.C. 1912. Den norske kirkes historie med portrætter,

faksimiler og billeder. Gyldendalske Boghandel,

Nordisk Forlag, Kristiania, Norway.

2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 175

Koht, H. 1921. Medførte kristendommens innførelse et

makttap for det gamle norske aristokrati? Originally

published in: Innhogg og utsyn 1921. Republished in:

A. Holmsen (Ed.). 1966. Norsk Middelalder. Utvalgte

avhandlinger for historiestudiet. Universitetsforlaget,

Norway. Pp 69–78.

Kolsrud, O. 1958. Noregs kyrkjesoga. Vol. I. Millomalderen,

Oslo, Norway.

Kragh, C. 1995. Kristendommen og social og politisk

endring i vikingtiden. Pp. 18–40, In A. Ågotnes (Ed.).

Kristendommen slår rot. Onsdagskvelder i Bryggens

Museum. Bryggens Museum, Bergen, Norway.

Kristjánsdóttir, S. 2004. The Awakening of Christianity in

Iceland. Discovery of a Timber Church and Graveyard

at Þórarinsstaðir in Seyðisfjörður. Gotarc, Gothenburg

Archaeological Thesis, Series B No 31. Gothenburg,

Sweden.

Kristjánsson, J. 1988. Eddas and Sagas. Iceland’s Medieval

Literature. Translated by Peter Foote. Hið íslenska

bókmenntafélag, Reykjavík, Iceland.

Krogh, K.J. 1975. Den islandske kolonisation.

K’ak’ortok’—Julianehåb 1775–1975. Julianehåb Museumsforening,

Qarqortoq, Greenland.

Krogh, K.J. 1982: Erik den Rødes Grønland. Nationalmuseets

Forlag, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Krogh, K.J. 1983. Gård og Kirke. Samhørighed mellem

gård og kirke belyst gennem arkæologiske undersøgelser

på Færøerne og i Grønland. Hikuin 9, Højbjerg,

Denmark.

Lidén, H.-E. 1991. Fra antikvitet til kulturminne: trekk av

kulturminnevernets historie i Norge. Universitetsforlaget-

Norwegian Univeristy Press, Oslo, Norway.

Lidén, H.-E. 1995. De tidlige kirkene. Hvem bygget

dem, hvem brukte dem og hvordan? Pp. 129–141,

In Lidén, H.-E. (Ed). Møtet mellom hedendom og

kristendom i Norge. Universitetsforlaget-Norwegian

Univeristy Press, Oslo, Norway. Also available online

at http://www.nb.no/utlevering/contentview.

jsf?urn=URN:NBN:no-nb_digibok_2008070804070.

Accessed 12 November 2010.

Lidén, H.-E. 2001. Middelalderens stenarkitektur i Norge.

In Norges kunsthistorie Vol. 2. [PROVIDE PUBLISHER],

Oslo, Norway.

Lidén, H.-E. 2008. Kirkene i Hordaland gjennom tidene.

Gyldendal, Bergen, Norway.

Lucas, G. (Ed.) 2009: Hofstaðir. Excavations of a Viking

Age Feasting Hall in North-Eastern Iceland. Institute of

Archaeology, Reykjavík, Iceland. Monograph No. 1.

Lucas, G., and T. McGovern. 2007. Bloody slaughter:

Ritual decapitation and display at the Viking settlement

of Hostaðir, Iceland. European Journal of Archaeology

10(1):7–30. Also available on-line at http://

eja.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/10/1/7.

Lynch, K. 1992. The Image of the City. 21st Edition. MIT

Press, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Lönnroth, L. 1963. Studier i Olaf Tryggvasons saga. Pp,

54–94, In Samlaren. Svenska Litteratursällskapet,

Uppsala, Sweden.

Løwe, G.C.V. 1995. Religionsskiftet i samspill med de

politiske maktforholdene i Norge. En historiografisk

undersøkelse. KULTs skriftserie nr. 72. Norges forskningsråd/

Norwegian Research Council, Oslo, Norway.

Friðriksson, A. 2004. The Topography of Iron Age Burials

in Iceland. Pp. 15–16, In G. Guðmundsson (Ed.).

Current Issues in Nordic Archaeology. Proceedings

of the 21st Conference of Nordic Archaeologists 6–9

September 2001 Akureyri Iceland. Society of Icelandic

Archaeologists, Reykjavík, Iceland

Gansum, T., G.B. Jerpåsen, and C. Keller. 1997. Arkeologisk

landskapsanalyse med visuelle metoder.

AmS Varia 28. Archaeological Museum in Stavanger.

Stavanger, Norway.

Geake, H. 2003. The Control of Burial Practice in Anglo-

Saxon England. Pp. 259–269, In M. Carver (Ed.): The

Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern

Europe AD 300–1300. The University of York,

York Medieval Press, York, UK.

Graham-Campbell, J., and C.E. Batey. 1998. Vikings in

Scotland: An Archaeological Survey. Edinburgh University

Press, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Gräslund, A.-S., and M. Müller-Wille. 1993. Gravskicket

i Skandinavien under Vikingatiden. Pp. 186–187, In

E. Roesdahl (Ed.). Viking og Hvidekrist. Norden og

Europa 800–1200. 22. Europarådsutstilling, Copenhagen,

Denmark.

Guldager, O., S. Stummann Hansen, and S. Gleie. 2002.

Medieval Farmsteads in Greenland. The Brattahlid

region 1999–2000. Danish Polar Center, Copenhagen,

Denmark.

Gwim, P. 2008. Lost Tribes of the Green Sahara. National

Geographic Magazine September 2008:126–143.

Helle, K. 1995a. Under Kirke og Kongemakt 1130–1350.

Aschehougs Norges Historie volume 3. Oslo, Norway.

Helle, K. 1995b. Kongemakt og kristendom. Pp. 41–54,

In A. Ågotnes (Ed.). Kristendommen slår rot. Onsdagskvelder

i Bryggens Museum. Bryggens Museum,

Bergen, Norway.

Hreinsson, V. (Ed.). 1997. The Complete Sagas of Icelanders.

Vols. I–V. Leifur Eiríksson Publishing, Reykjavík,

Iceland.

Imsen, S. 2003. Nidarosprovinsen. Pp. 15–45, In S. Imsen

(Ed.). Ecclesia Nidrosiensis 1153–1537. Søkelys på

Nidaroskirkens og Nidarosprovinsens historie. Tapir

akademisk forlag, Trondheim, Norway.

Iversen, F. 2004. Eiendom, makt og statsdannelse: Kongsgårder

og gods i Hordaland i yngre jernalder og middelalder.

Universitetet i Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Jackson, T.N. 1994. The Role of Óláfr Tryggvason in the

Conversion of Russia. Pp. 7–25, In M. Rindal (Ed.).

Three Studies on Vikings and Christianization. KULTs

skriftserie No. 28/RELIGIONSSKIFTET No. 1. The

Research Council of Norway, Oslo, Norway.

Keller, C. 1991. The Norse in the North Atlantic. A model

of Norse Greenlandic Medieval society. Pp. 126–141,

In G.F. Bigelow (Ed.). The Norse of the North Atlantic.

Acta Archaeologica vol. 61. Copenhagen, Denmark.

Keyser, R. 1856–58. Den norske Kirkes Historie under

Katholisismen. Vols. I–II. Tønsbergs Forlag, Christiania,

Norway.

KLNM – Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder

fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 1956–1968.

Vols. 1–21. Facsimile 1980 by Rosenkilde og Bagger,

Copenhagen, Denmark.

176 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Sawyer, B., P. Sawyer, and I. Wood (Ed.s) 1987: The

Christianization of Scandinavia. Report of a Symposium

held at Kungälv, Sweden 4–9 August 1985.

Viktoria Bokförlag, Alingsås, Sweden.

Sawyer, P. 1987. The process of Scandinavian Christianization

in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Pp. 68–87,

In B. Sawyer, P. Sawyer, and I. Wood (Eds.).The

Christianization of Scandinavia. Report of a Symposium

held at Kungälv, Sweden 4–9 August 1985.

Viktoria Bokförlag. Alingsås, Sweden.

Schumacher, J. 1987. Kirken i middelaldersamfunnet.

Series Kristendommen i Europa 2. Tano A.S., Oslo,

Norway.

Seaver, K.A. 1996: The Frozen Echo. Greenland and the

Exploration of North America, ca. A.D. 1000–1500.

Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, USA.

Sigurðsson, J.V. 2003a. Kristninga i Norden ca 750–1200.

Det norske samiaget, Oslo, Norway.

Sigurðsson, J.V. 2003b. Island og Nidaros. Pp. 121–140,

In S. Imsen (Ed.) Ecclesia Nidrosiensis 1153–1537.

Søkelys på Nidaroskirkens og Nidarosprovinsens historie.

Tapir akademisk forlag, Trondheim, Norway.

Sigurðsson, J.V. 2004. Innledning. Pp. 5–12, In J.V.

Sigurðsson, M. Myking, and M. Rindal (Eds.). Religionsskiftet

i Norden. Brytninger mellom nordisk og

europeisk kultur 800–1200 e.Kr. Occasional papers

Skriftserie 6/2004. Senter for studier i vikingtid og

nordisk middelalder, Oslo, Norway.

Sigurðsson, J.V., B. Gjerland, and G. Losnegård. 2005.

Ingólfr. Norsk-islandsk hopehav. Selja forlag, Førde,

Norway.

Sturlusson, S., F. Hodnebø, L.M. Hollander, and K.A.

Lie. 1987. Snorri: The Sagas of the Viking Kings of

Norway: Heimskringla / with the original saga illustrations

by Halfdan Egedius… et al. Translated by L.M.

Hollander. F. Hodnebø and K.A. Lie (Eds.). Stenersen,

Oslo, Norway.

Sognnes, K. 1988. Sentrumsdannelser i Trøndelag. En

kvantitativ analyse av gravmaterialet fra yngre jernalder.

Pp. 59–65, In Fortiden i Trondheims bygrunn:

Folkebibliotekstomten. Meddelelser Nr. 12, Trondheim,

Norway.

Solberg, B. 2000. Jernalderen i Norge: ca. 500 f.Kr. –

1030 e.Kr. 2nd Edition. Cappelen, Oslo, Norway.

Stefánsson, M. 1995. Islandsk egenkirkevesen. In H.E.

Lidén (Ed.). Møtet mellom hedendom og kristendom

i Norge. Universitetsforlaget-Norwegian University

Press, Oslo, Norway.

Steinsland, G. 2005. Norrøn religion. Myter, riter, samfunn.

Pax Forlag A/S, Oslo, Norway.

Sveaas Andersen, P. 1995. Samlingen av Norge og kristningen

av landet. 800–1130. 2nd Edition. First published

in 1977 In K. Mykland (Ed.). Handbok i Norges

historie, Scandanavian University Books. Universitetsforlaget

, Bergen, Oslo, Norway.

Taranger, A. 1890: Den angelsaksiske kirkes indflydelse

paa den norske. Den norske historiske forening, Kristiania,

Norway.

Tryti, A.E. 1987. Kirkeorganisasjonen i Bergen

bispedømme i første halvdel av 1300-tallet. Upublisert

hovedfagsoppgave i historie, Universitetet i Bergen.

Bergen, Norway.

Maher, R.A. 2009. Landscapes of life and death: Social

dimensions of a perceived landscape in Viking Age

Iceland. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. The City

University of New York, New York, NY, USA. Available

online at http://www.nabohome.org/postgraduates/

theses/ram/. Accessed 10 November 2010.

Maurer, K. 1855–56. Die Bekehrung des norwegischen

Stammes zum Christenthume: in ihrem geschichtlichen

Verlaufe quellenmäßig geschildert. I–II. Kaiser,

Munich, Germany.

Maurer, K. 1895. Nogle Bemærkninger til Norges Kirkehistorie.

Historisk Tidsskrift, Kristiania, Norway.

Meaney, A.L. 2003. Anglo-Saxon pagan and early Christian

attitudes to the dead. Pp. 229–241, In M. Carver

(Ed.). The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion

in Northern Europe AD 300–1300. The University of

York, York Medieval Press, York, UK.

Morris, R. 1989. Churches in the Landscape. Phoenix Giant,

London, UK.

Müller-Wille, M. 1970. Bestattung im Boot. Studien zu

einer europäische Grabsitte. Offa 25/26.

Myking, M. 2001. Vart Norge kristna frå England? Ein

gjennomgang av norsk forsking med utgangspunkt

i Absalon Tarangers avhandling Den angelsaksiske

kirkes indflytelse paa den norske (1890). Centre for Viking

and Medieval Studies, Oslo, Norway. Occasional

papers 1/2001

Ólason, V. 1998. Dialogues with the Viking Age. Narration

and representation in the Sagas of the Icelanders.

[Original title: Samræður við söguöld.]Translated by

Andrew Wawn. Heimskringla, Reykjavík, Iceland.

Olsen, M. 1928. Farms and Fanes of Ancient Norway. The

place-names of a country discussed in their bearings

on social and religious history. H. Aschehoug and Co.

(W. Nygaard), Oslo, Norway.

Olsen, T.B. 2010. Jordbruksbosetning på Hjelmeset gjennom

4000 år. Arkeologiske undersøkelser på Hjelmeset,

Gloppen k., Sogn og Fjordane. Prosjekt Sandane

lufthavn og Hjelmeset lok. 7. Arkeologiske rapporter

fra Bergen Museum nr. 1/2010. Bergen, Norway.

Øye, I. (Ed.). 2002. Vestlandsgården – fire arkeologiske

undersøkelser, Havrå – Grinde – Lee – Ormelid. Arkeologiske

avhandlinger og rapporter 8 fra Universitetet

i Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Richards, J.D. 2003. Pagans and Christians at a frontier:

Viking burial in the Danelaw. Pp. 383–385, In M.

Carver (Ed.). The Cross Goes North: Processes of

Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300–1300. The

University of York, York Medieval Press, York, UK.

Robinson, C.H. 1921. Anskar, The Apostle of the North,

801–865. Translated from the Vita Anskarii by Bishop

Rimbert his fellow missionary and successor. The

Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign

Parts, London, UK.

Roussell, A. 1941. Farms and Churches in the Mediaeval

Norse Settlements of Greenland. Meddelelser om

Grønland vol. 89 (I). Copenhagen, Denmark.

Sawyer, B. 1987. Scandinavian conversion histories. Pp.

88–110. In B. Sawyer, P. Sawyer, and I. Wood (Eds.).

The Christianization of Scandinavia. Report of a Symposium

held at Kungälv, Sweden 4–9 August 1985.

Viktoria Bokförlag, Alingsås, Sweden.

2010 B. Gjerland and C. Keller 177

11Named after Pope Gregorius VII (A.D. 1073–1085),

known from his showdown with Henry IV in Canossa

A.D. 1077. The Gregorian Reform with its slogan “libertas

ecclesiae’ was developed in Cluny, west of the Rhine,

in a feudal context (Schumacher 1987:67)

12From A.D. 1103, Lund (at the time under Denmark, but

located in present-day Sweden) had taken over as the

Archbishopric of the Nordic countries. The Archbishopric

of Niðarós was constructed by transferring some

of the area under the Archdioceses of Lund and York to

Niðarós, thus joining the Norse North Atlantic under a

single, administrative unit. It consisted of Norway, Iceland,

Greenland, Faroes, Orkney, and Man and the Isles,

areas where Old Norse was spoken or understood.

13“Bergen Kalvskinn”: Cadastre for the Bergen diocese

from the mid-fourteenth century (http://gandalf.aksis.