52 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

*Balliol College, Broad Street, Oxford OX1 3BJ, UK; lesley.abrams@balliol.ox.ac.uk.

Introduction

During the Viking Age, everyone in the Norse

world had one experience in common. In Norway,

Denmark, and Sweden, and in the settlements in Russia,

eastern and northern Britain, Ireland, Normandy,

and the North Atlantic, they all began to abandon

their traditional religion for the Christianity which

was practiced by the superpowers of their day. Christianity

is of course a religion based on a more or less

unchanging book, with well-articulated doctrines

and strictly prescribed ritual practices. But this fi xed

center has been accompanied by a remarkable fl exibility

when it comes to applying religion to real life.

In every conversion context, Christianity has had

to convince people that their own religious practice

was, fi rst, inadequate, and then, unacceptable. Yet in

the process, the Church has had to face the primary

fact of any missionfi eld: that what could change and

what had to stay the same varied from place to place.

Wherever it faced the challenge of conversion,

Christianity worked its way into traditional habits

of understanding life and the world, and as a result,

Christian societies of very different character were

created, bringing different measures of continuity

and change depending on local circumstance. This

process is obscure—only fi tfully illuminated across

the Scandinavian world— and for Greenland even

more than other settlements of the Viking Age the

question of how the transition from one religion to another

worked in practice can only have hypothetical

answers. The exercise of speculation may, however,

help us to think more critically about the character of

Greenland’s society in its fi rst generations.

Historiography of Conversion

For much of the middle ages, the model of historical

writing was Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis

anglorum, the Ecclesiastical History of the English

People (Colgrave and Mynors 1969). Bede’s work

was completed in northern England in AD 731, but

it had tremendous staying-power. His history of the

English conversion fundamentally conditioned the

way that subsequent Christian writers chose to represent

the process of religious change. It is easy to

forget how infl uential these constructed Christian

templates have been on our thinking. Although there

is as yet no defi nite proof that Bede’s Historia was

known to the earliest Icelandic historians, his chronological

works were used and referred to, and Benedikt

Benedikz (1976:340) supposed that the Historia “was

absorbed into the bloodstream of the writing of the

golden age of Icelandic historiography” (Phelpstead

2006:54–57, Turville-Petre 1972:104–107). In order

to consider the religious condition of the early

Greenlanders, we need to remember this and ask just

how infl uential ecclesiastical convention might have

been in shaping the settlement’s record of its past.

Ari the Learned’s history of Iceland, Íslendingabók

(Benediktsson 1968, Grønlie 2006), was probably

inspired by Bede’s Historia, and if in their turn, educated

Greenlanders had written the history of their

settlement and its conversion to Christianity, it would

in all likelihood have been in Bedan terms.

They did not do so, as far as we know, and,

while we can regret the lack of a surviving history

of this sort, there may be an unexpected advantage

as a result. In Bede, pagan people were converted

Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement

Lesley Abrams*

Abstract - While the beginnings of Christianity in Greenland are very poorly recorded, the settlement has played a prominent

role in the discussion of paganism, the conversion, and early Christianity in the Viking world, thanks to the sagas in

which Greenlanders feature. In particular, the range of religious practice that is refl ected in the literary representations of

the past is very striking; the rituals of the seeress, Thorbjorg, the Christian practice of Eric’s wife, Thjodhild, and Gudrid’s

pilgrimage to Rome and profession as a nun offer contrasting perceptions of lived religion in the late Viking Age. While the

absence of other relevant sources relating to Greenland is clearly a disadvantage, it leaves us free to question entrenched

assumptions about the early religious life of the community.

While, as elsewhere, the conversion to Christianity in Greenland would have had a practical impact, ranging from the

creation of political and economic alliances to changes in social custom (including burial and memorialization), I argue in

this paper that Greenland might have been somewhat different from other Scandinavian communities overseas. Discussing

and drawing on the written and material record, I propose that we might gain from resisting the narrative of Christian convention,

which requires sudden, dramatic, and emphatic change, in favor of a different understanding of religious practice.

If we entertain the possibility that some societies may have had more room for religious diversity than Christian sources

would allow, it could be argued that the early community of Greenland, instead of conforming to Christian stereotype,

experienced an extended period of diversity; a mixed society encompassing traditional religious practice and a largely domestic

Christianity could have continued for some time until Christianity gained a suffi cient degree of institutionalization

to impose a more conventional Christian way of life.

2009 Special Volume 2:52–65

Norse Greenland: Selected Papers from the Hvalsey Conference 2008

Journal of the North Atlantic

2009 L. Abrams 53

in a moment—by winning on the battlefi eld, for

example, or being rounded up and taken down to

the river for baptism on the order of a king. People

“became” Christian because kings said they should

and because missionaries were on hand to effect the

ritual which would transfer them from one religion

to another. Baptism equalled conversion. However,

it is quite clear that in real medieval life, outside the

conventions of narrative, conversion unwound on a

much slower time scale. Surviving texts from betterdocumented

regions, not to mention analogy from

anthropological study of more modern populations,

suggest that, no matter how the Church wanted it to

be seen, conversion was not something effected in

a moment, no matter how important some moments

were. Furthermore, traditional, pre-conversion, religion

and Christianity were not two different but

equal entities which could simply be exchanged, replacing

one with the other. Writing and the conventions

of written recording arrived with Christianity,

and all written accounts refl ect that connection, consciously

or not. Their conventions require sudden

dramatic change and the substitution of one religion

with another, but this does not capture the complexity

of the situation. Any story set in the ninth, tenth,

or eleventh centuries written along those lines would

presumably be inaccurate.

If, on the other hand, Greenlanders had composed

a saga account of the origins of Christianity,

we might have had a Leifs saga or a Þjóðhildar

saga, attributing the conversion to its central character.

But this too would be problematic. Saga-writers

and (re-writers) had various aims and concerns,

family validation and lineage construction high

amongst them. The genre could have been used retrospectively

to attribute (or misattribute) to particular

individuals the momentous change that had occurred

in the settlement’s religious character when

it became Christian. The concern to give religious

weight to forbears of important contemporaries

certainly had an impact on what literature survives.

It has been suggested, for example, that Eiríks saga

was rewritten to magnify the exploits of Thorfinn

Karlsefni, the ancestor of Hauk Erlendsson, who

produced a version of the saga some time before

his death in AD 1334 (Wahlgren 1993:704; see also

Vohra 2008). In Grænlendinga saga, Thorstein

Eiriksson’s prophecy of the future of Thorfinn’s

wife, Gudrid—she will make a pilgrimage to Rome,

she will build a church, she will become a nun—

establishes her as the overwhelmingly appropriate

ancestor of churchmen and churchwomen, a holy

forbear, as Ólafur Halldórsson (1978:392–394,

452; 2001:42) has noted. How accurately it reflects

her real religious life is another matter. The role attributed

to Eirik’s wife Thjodhild as the founder of

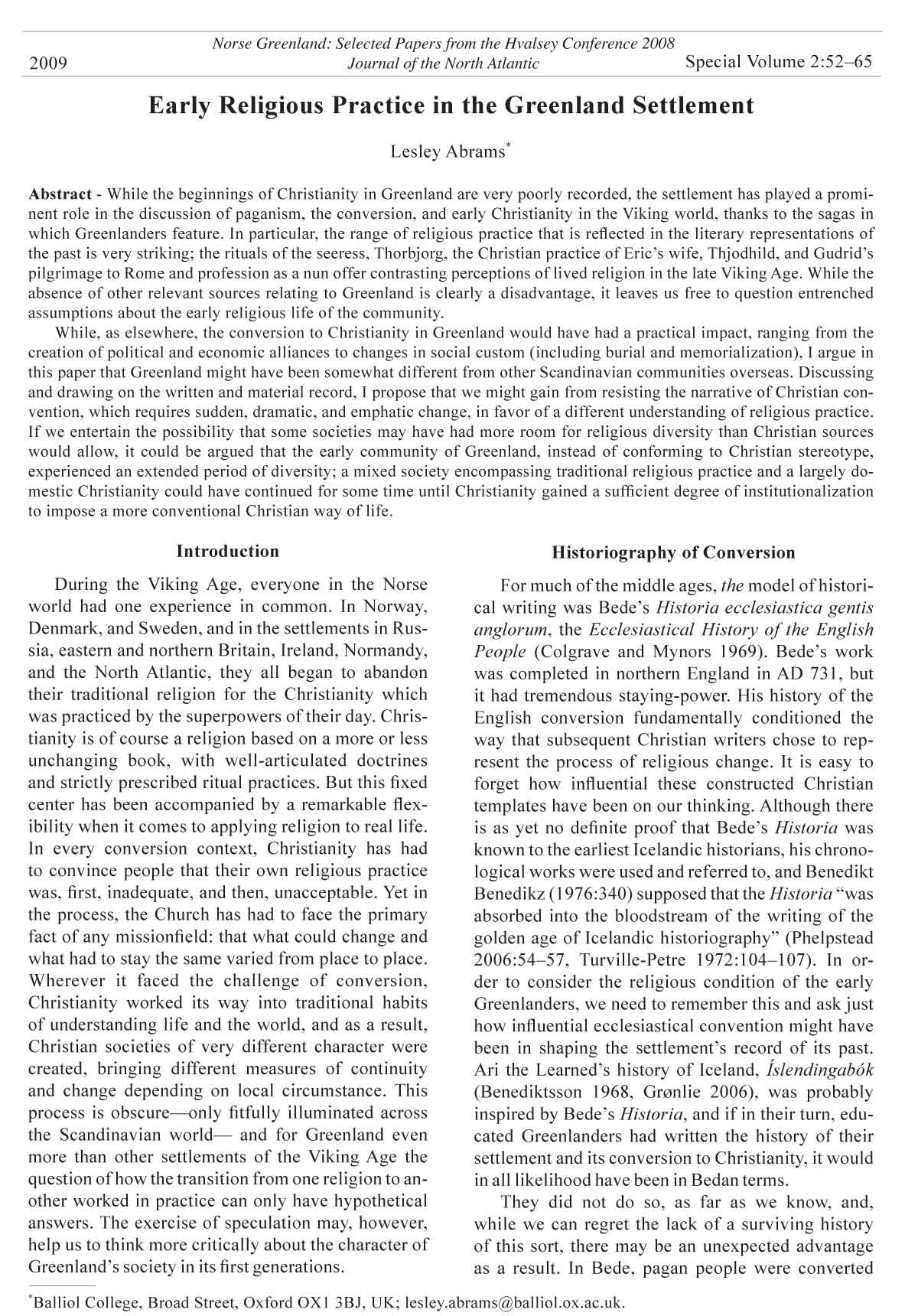

Greenland’s first church (Fig. 1) similarly derives

from a story in Eiríks saga, which throws the spot-

Figure 1. The replica in Qassiarsuk of the small church excavated at the same site in the 1960s and commonly associated

with the church of Thjodhild. See also Figure 4. Photograph © Jette Arneborg.

54 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

light on Gudrid’s association with Eirik’s family.

In addition to distortion motivated by family concerns,

the sagas may misrepresent more generally

by suggesting that the first people to adopt the new

religion were those of the highest status. So this

vernacular convention may be misleading as well.

It is of course no surprise that literary conventions

make for bad history, if history means an exact

representation of past events. If we want to think

about religious life in the early stages of the settlement,

the absence of both ecclesiastical chronicles

and sagas recounting the interaction between pagans

and Christians and the attitudes of Greenlanders on

both sides of the religious divide is a real drawback,

whatever the fl aws of the genres. But, to look on the

bright side, their absence gives us the opportunity to

construct an independent picture of the early stages

of Christianity in Greenland. A narrative of the progress

of Christianity in the fi rst generations is out of

the question. But another look at the small amount

of written and archaeological evidence, seen in the

light of comparative anthropological material, suggests

that some entrenched assumptions about religious

life in the early generations of the Greenland

settlement can be questioned.

Converting to Christianity

Exactly what were people doing when they

converted to Christianity? What happened to their

lives? These questions are usually addressed by

looking at sources steeped in ecclesiastical convention.

In classic conversion narratives, conversion

was an instrument of royal policy. If it was not

forced upon people by oppressive secular power,

it was usually a choice—conventionally, Christianity

was the deserved winner of a contest over who

would be in charge of managing society’s relations

with the supernatural. The choice involved material

considerations (would the new religion bring greater

wealth?), political considerations (would it increase

the king’s power?), social considerations (would

it strengthen family ties?), or legal considerations

(would it keep better order?). These are clearly

matters of authority, not faith, matters of practical

living, not believing. The touchpoint was the performance

of ritual, which acted as a binding force, but

also clarifi ed who did not belong. While faith was

extremely important, it was faith in the new power

that really mattered. Ruth Mazo Karras (1997:110)

has noted that the sagas portray Christ as a more

effective overlord and a better patron, and offer his

superiority in this department as a good reason to

convert. These are material, not philosophical or

theological considerations.

Nevertheless, I suspect that there was far more

discussion, debate, and disagreement than the conventional

conversion narratives allow for. I fi nd it

hard to imagine that medieval people were simply

passive consumers of the new religion. Reconstructions

of the conversion period in sagas certainly

imagine otherwise, as in Njáls saga, where the poetess

Steinunn “lectured [the missionary Thangbrand]

for a long time and tried to convert him to paganism.

[He] listened to her in silence but when she had

fi nished he spoke at length, turning all her own arguments

against her” (ch. 102; Magnusson and Pálsson

1960:219–222; Sveinsson 1954:265–267). The saga

author may have been speculating about the past as

much as we are. But even if a society could be offi

cially “converted” in one decisive moment, as in

Iceland in AD 999, we must question how far this

could have gone. New beliefs must be taught, new

practices accepted. The process of convincing individuals

and making the new religion a fundamental

part of their lives must have taken time. The transformative

message would fi nd different responses

depending on whether the audience was forwardlooking

and eager to take on the new, or reactionary

and resistant to change. Greenland’s early settlers

could plausibly have been of either sort—while pioneers

are progressive, “ex-pat” societies are often

more conservative than those they have left behind.

Anthropology can offer better recorded contexts

for comparison. Students of Africa, for example,

have claimed to be able to chart the movement of

Christianity into the continent with some precision;

they can identify the names and biographies

of the missionaries who were sent from the various

colonial powers and can assemble details about

the training of these men and women, their methods,

where they were sent, and what they did—all

this is available through surviving records, and it

has been used to write the history of Africa’s conversion

to Christianity. But, as Adrian Hastings

(1994:437–438) has pointed out, the reality on the

ground, “the black advance” of Christianity, was in

fact “far more low-key, often entirely unplanned or

haphazard.” Africans had far more agency in their

conversion than the missionary-centered narrative

reveals. Although the written sources accurately

refl ect the missionary life, they avoid (or are ignorant

of) other truths. African converts, in the words

of David Maxwell (1999:3–4), “appropriated the

symbols, rituals, and ideas of Christianity and made

them their own,” creating an indigenous Christianity

after an extended dialogue between missionary

Christianity and African culture. Perhaps the model

of an extended dialogue would suit the fi rst stages

of Christianity in the early medieval world as well.

Maybe conversions were more low-key, haphazard,

and unplanned in the early middle ages than the

sources suggest. This might explain a disturbing

statement from Hamburg-Bremen, probably added

2009 L. Abrams 55

to the history of its Church around AD 1300, about

Goutlande, Swetide, [and] Grenelande:

The peoples claim that they are in part Christian,

even though they are without faith and without

confession and without baptism. In part, they even

worship Jupiter and Mars, although they are likewise

Christian (Schmeidler 1917:286, Tschan and

Reuter 2002:228).

Given that the text goes on to say that Icelanders’

noses freeze and come off if they wipe them, we

are dealing here with something other than factual

reporting. But the tradition represented in this

statement—of a less than embedded Christianity

and a society that did not conform to contemporary

convention—may in its own suggestive way be as

reliable as the other sources on which we rely.

Christianity in Greenland

We are very much in the dark when it comes to

hard facts about the religious situation in Greenland

in the early settlement. Several of the fi rst settlers

were fi rmly associated with paganism in later vernacular

tradition, especially in the two surviving

sagas which focus on the voyages to Vinland, Eiríks

saga rauða and Grænlendinga saga (Magnusson

and Pálsson 1965, Sveinsson and Þórðarson 1935).

Eirik is a committed pagan; Thorbjorg the seeress

conducts rituals at a feast at Herjolfsness (Eiríks

saga ch. 4); and one of the Vinland travellers, the

hunter Thorhall, composer of a poem for “my patron,

Thor,” seeks supernatural assistance when the food

supply runs low (Eiríks saga ch. 8). The text on a

rune-stick from Narsaq (Fig. 2) may suggest that

Greenland’s residents were familiar with mythological

stories—no more so, of course, than later

Christian writers in Iceland, but the suggested dating

of the rune-stick to the period AD 985x1025 may

make it an early witness, and therefore potentially

from a pagan context (Stoklund 1993: 47–50).1 Unfortunately,

there is very little physical evidence to

attest to active paganism in the settlement, beyond a

small fragment of steatite found in 1932 in the barn

and byre complex at Qassiarsuk (Ruin 19, Ø29)

decorated with a Thor’s hammer (Fig. 3; Arneborg

n.d.:31,36; Krogh 1967:23). If the settlers were not

yet Christian, the lack of any discovered remains

of so-called pagan burials is puzzling—almost all

the excavated burials have been in churchyards

(Lynnerup 1998:11–33, 51–52)—but there could be

reasons other than the abandonment of paganism to

account for the lack of burials with grave-goods.

Furnished inhumations may have been associated

with particular circumstances or social groups, as

they were not the only form of burial in Iceland (or

Scandinavia) in the late tenth century (Eldjárn and

Friðriksson 2000:550–551). Pre-Christian graves

could perhaps have been moved to churchyards at

a later date. Furthermore, problems of preservation

and discovery in the less-settled and more extreme

Figure 2. The rune-stick from Narsaq. Photograph © National Museum of Denmark.

56 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

landscape of Greenland may conspire against the

identifi cation of such graves.

If we turn to evidence of the conversion itself,

it is in short supply. The kinds of external forces

that usually brought missionary initiatives and political

and social pressure for conversion can not

be identifi ed for certain. Greenland, like Iceland,

had no king in whose interests the new religion

might have acted. When Adam of Bremen, in the

history of his Church which he wrote in the 1070s,

the Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontifi cum,

declared that Christianity had “recently” reached

Greenland (Schmeidler 1917:274, Tschan and Reuter

2002:218), it is diffi cult to know what he meant.

Adam also said that Greenlanders (along with

Icelanders and legates from Orkney) had travelled

to Bremen and begged Archbishop Adalbert (AD

1043–1072) to send preachers, and that the archbishop

had obliged (Schmeidler 1917:167, Tschan

and Reuter 2002:134). The see of Hamburg-Bremen

had been founded in the ninth century to evangelise

the pagan peoples of the North, and it cited papal

authority for its claim to jurisdiction over the whole

of the Scandinavian world (Abrams 1995a:esp.

229–238). It seems to have sent a mission to Iceland

in the 980s, and Isleif Gizurarson, the fi rst Icelandic

bishop, was consecrated in Hamburg-Bremen in AD

1056, returning to his country, according to Adam,

with letters from the archbishop addressed to the

people of both Iceland and Greenland (Schmeidler

1917:273, Tschan and Reuter 2002:218). Perhaps,

as Ólafur Halldórsson (1981:204) has said, the assumption

was that Isleif, in the absence of other

offi cial bishops in the region, would take responsibility

for Greenland as well., However, Adam’s

statement is not equivalent to real information about

Figure 3. Steatite loom-weight from Qassiarsuk decorated with a Thor’s hammer. Photograph © National Museum of Denmark.

2009 L. Abrams 57

the religious situation in Greenland at the time. Isleif

was a missionary bishop (Vésteinsson 2000:19–24),

and the authority of the German see over Iceland’s

developing Church could have been quite tentative.

The latter’s activity was likely to have extended to

Greenland only if the two formed a single ecclesiastical

unit at the time. The Historia Norvegiae,

written in the second half of the twelfth century,

possibly in eastern Norway, says that Greenland was

“discovered, settled, and confi rmed in the Catholic

faith by Icelanders” (a telensibus reperta et inhabita

ac fi de catholica roborata) (Ekrem and Mortensen

2003:54–55, for the date and location:11–24), but

this statement of a more general Icelandic connection

is not necessarily evidence of a concerted program

of religious mission.

Hamburg-Bremen was itself clearly active in

some parts of the North Atlantic in the second

half of the eleventh century; Adam names three

Hamburg-Bremen appointees to Orkney in Archbishop

Adalbert’s time (Abrams 1995b:28–30).

However, after Adalbert’s death, bishops for Orkney

were appointed in York (Crawford 1983:105–108).

There is plenty of evidence that Hamburg-Bremen

experienced increasing diffi culty maintaining its

northern monopoly, especially against the English.

Michael Gelting (2004) has argued that Hamburg-

Bremen had lost control over the Danish Church

as early as AD 1059. Increasing stress is refl ected

in Adam’s pages as the archbishops enlisted papal

support against the competition. Adam quotes a letter

from Pope Alexander II (AD 1061–1073) to the

Danish bishops reminding them of their obligations

to Hamburg-Bremen (Schmeidler 1917:221–222,

Tschan and Reuter 2002:181–182). Alexander also

wrote to the Norwegian king, Harald harðráði

(AD 1046–1066), reprimanding him for preferring

English and French bishops to those of the German

see (Schmeidler 1917:155–157; Tschan and Reuter

2002:125; Abrams 1995a:229–236; Sawyer et al.

1987:81–83, 92–94). However, while the papacy

had initially promoted Hamburg-Bremen’s rights, it

changed its tune in the last quarter of the eleventh

century, when it needed allies against the German

emperor. Thereafter, it supported Scandinavian independence

at the expense of the archdiocese’s claims

(Abrams 1995a:237–238). Popes wrote to the kings

of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, suggesting ways

in which direct links with Rome could be strengthened,

bypassing Hamburg-Bremen.

Ólafur Halldórsson (1978:xi, 443; 2001:44) has

cited a letter from Pope Leo IX to the archbishop of

Hamburg-Bremen dated AD 1053 as evidence that

the people of Greenland fell under the jurisdiction of

the German see by the mid-eleventh century. However,

Leo’s is not the earliest Hamburg-Bremen text

to mention Greenland. Several documents enumerating

the northern places controlled by the diocese lay

claim to ecclesiastical authority in Greenland from

the early ninth century—some centuries before it

was even colonized. Hamburg-Bremen’s notorious

forgeries were apparently created to support the

see against increasing competition (Curschmann

1909:122–129, Schmeidler 1918:195–203, Tschan

and Reuter 2002:23). Documents in the names of

popes Gregory IV (AD 827–844), Nicholas I (AD

858–867), Anastasius III (AD 911–913), John X

(AD 914–928), Leo IX (AD 1048–1054), Victor II

(AD 1054–1057), and Innocent II (AD 1130–1143)

claim Greenland among Hamburg-Bremen’s fl ock.

Papal recognition of Greenland is probably most

likely to have occurred after it acquired its own

bishop, but, as we shall see, this does not appear

to have happened before the twelfth century; direct

contact between Greenland and the pope through

the payment of tithe is not attested before the

thirteenth century (Arneborg 2000:315). Although

the privilege of Leo IX may have been authentic

(Curschmann 1909:3, Schmeidler 1918:251–252),

it seems that Adam had no knowledge of the document

in the 1070s; he discusses the protracted negotiations

between Leo and Adalbert relating to the

creation of a patriarchate (Schmeidler 1917:175,

Tschan and Reuter 2002:140–141), but does not cite

the pope’s privilege. Unfortunately the document

was lost in 1943 when the Hamburg archives were

bombed. Even if the reference to Greenland was indeed

original and not a later interpolation, Leo IX’s

statement of authority over the settlement may have

been more aspirational and symbolic than real.

The challenge offered by foreign missionaries

seems to have begun to leave its mark on Hamburg-

Bremen’s documents in the second half of the eleventh

century (Curschmann 1909:123–129), while a

visit to Rome by two of its archbishops in the 1120s

to plead their cause has aroused particular suspicion

(Christensen 1976:31–35). The politics that

encouraged this manipulation of the archive may lie

behind Greenland’s development of a connection

with the Church in Scandinavia, bypassing Iceland.

The early twelfth century was a time of significant

change in episcopal organization, when Hamburg-

Bremen’s authority was being further undermined

by the creation of new sees. As Jette Arneborg

(1991:145) has pointed out, the establishment of a

diocese in Greenland belongs to the period of episcopal

foundations emanating from the new archbishopric

of Lund, itself created in AD 1103–1104.

New sees were created for Oslo, Bergen, Nidaros,

and, indeed, for Iceland; Jon Ogmundarson, first

bishop of Hólar, was consecrated by Asser, archbishop

of Lund, in AD 1106. Although it did not

58 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

give in easily, by the mid-twelfth century Hamburg-

Bremen had lost its status as the primary player in

northern mission.

Christianity in the Literary and Material Record

Other external forces are identifi ed as instruments

of Greenland’s conversion in saga tradition. While

Eirik’s son Leif was singled out as the agent who

brought Christianity to the settlements, fi rmly placing

responsibility for this crucial development with

the founding family, the missionary activities of the

Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason formed the background

context. Olaf’s Christianity probably had its

roots in England. Sverre Bagge (2006) has argued

that eleventh-century traditions of Olaf’s Christianization

of Norway were picked up and highlighted

by later writers such as Oddr Snorrason (ca. AD

1190) and Snorri Sturluson in his Heimskringla (ca.

AD 1230). Various twelfth- and thirteenth-century

sources credit the king with conversions throughout

the North Atlantic zone (of Iceland in Ari’s Íslendingabók,

ch. 7, for example; of Shetland, Orkney, the

Faroes, and Iceland in Historia Norvegiae; Ekrem

and Mortensen:94–95). We are told, says Oddr in

his Saga Olafs Tryggvasonar (ch. 52; Andersson

2003:101–102, Jónsson 1932:154–155), that Olaf

converted fi ve countries, but the list that Oddr gives

includes a sixth—Greenland. In Heimskringla, the

king was made responsible for the conversion of

Orkney and Iceland (Saga Olafs Tryggvasonar, chs.

47, 73, 84, and 95) before he baptized Leif and commissioned

him to preach in Greenland (chs. 86 and

96; Halldórsson 1981:205–207; Hollander 1964:218,

228). Eiríks saga, which stresses Leif’s role, could

have been particularly influenced by Gunnlaug

Leifsson’s Latin saga about the Norwegian king,

composed in Iceland in the early thirteenth century

but now largely lost, where Olaf’s missionary activities

seem to have had particular importance (Wahlgren

1993:704).

Although there is no great narrative of conversion

in Eiríks saga and Grænlendinga saga, they

both show interest in the religious life of the early

settlement, but with varying emphases and different

detail. Both sagas specify that Greenland was

a “heathen country,” settled before the official

conversion of Iceland to Christianity (Eiríks saga

ch. 5, Grænlendinga saga ch. 2). Everything revolves

around individuals in Eirik’s family circle.

In Grænlendinga saga, Thorvald Eiriksson’s death

in Vinland provides an opportunity to stress his

Christianity; back in Greenland, we are told, Christianity

was in its infancy, and Eirik had died a pagan

(chs. 5–6). The saga ends with the proclamation

of the Christian credentials of Thorstein’s wife

Gudrid. Eiríks saga in its current form opens with

the story of Aud the Deep-Minded, whose entourage

included Gudrid’s Christian grandfather. Gudrid’s

own Christianity is highlighted by its opposition to

the paganism of Thorbjorg the seeress. Thjodhild is

converted by her son Leif. The few further incidents

or comments included in Eiríks saga which give

color to the conversion story are all associated with

Eirik’s family. Thjodhild refuses to sleep with him

after she becomes a Christian. She builds a church

at some distance from the farm (Figs. 1 and 4). Her

son Thorstein complains about Christians being improperly

buried in unconsecrated ground rather than

in proper churchyards (Eiríks saga chs. 5–6).

These details portray an alternative process of

conversion, through peer pressure and social levers,

rather than by oppressive external intervention, and

they may be true or they may be invention. Stories

nonetheless refl ect a community’s conception of its

past, and they also explain what they fi nd in the landscape.

Carbon-14 dates for skeletons found around

the turf church at Qassiarsuk (Fig. 4), well known

for its attribution to Eirik’s wife, Thjodhild, place

Christian burials there at an early period (Arneborg

2001:127, 130; Arneborg et al. 1999:161, 163).

Arneborg (n.d.:30, 33) has pointed out that the 143

graves in the churchyard were not much disturbed,

concluding that surface markers must have existed.

In one mass grave, the remains of 13 disarticulated

individuals were found, and a number of other

graves contained disarticulated skeletons (Krogh

1967:31–37, Lynnerup 1998:53–54). Shipwrecks,

other deaths far from home, or the reburial of pagan

remains could account for this feature of the cemetery.

Arneborg (2001:129) has argued that, because

several of the 9 dated skeletons were so early, the

church belonged to the landnám phase and catered

to the fi rst settlers, some of whom were already

Christian. She noted that a domestic building next

to the turf church, excavated in 1974, was probably

contemporary with it (Arneborg n.d.:23). Arneborg

has also provided potentially eleventh-century dates

for 2 samples of human bone from the churchyard

at Kilaarsarfi k in the Western Settlement associated

with the Viking-Age farm of Sandnes (AD

1021–1151 and 1030–1116, at one sigma; Arneborg

2001:127–128, 130).2

Although the cemeteries at Qassiarsuk and Kilaarsarfi

k provide important physical evidence of

early Christian communities, the exact application

of C14 results remains problematic. It seems overly

precise, for example, to describe an ox bone with a

calibrated date-range of AD 960–1040 (accurate to

only one sigma) which was found in a communal

grave in the cemetery of Qassiarsuk’s turf church

as representing settlers and their cattle at “precisely”

the landnám date of AD 985 (Arneborg et al.

1999:163). Three samples from that cemetery with

2009 L. Abrams 59

more which resemble its later church (Guldager et

al. 2002:45–47, 55–57, 66–67, 87–89, 116–118).

Arneborg’s ongoing research will represent a major

step forward in our understanding of the chronology

and context of Greenland’s small church sites. They

belong to a type which can be identifi ed elsewhere

in the North Atlantic world, and there is some disagreement

about whether they represent “early” use,

being replaced by a later rectangular style of building

(Fig. 6), or whether they continued as a type

throughout the middle ages. There is also the issue

of whether these types of church were necessarily

proprietary, and therefore replaced by new churches

when centralized ecclesiastical organization developed,

or whether they too could have been incorporated

in the diocesan structure (Stummann Hansen

and Sheehan 2006, Vésteinsson 2005:75–79, Wood

2006:92–108). While small churches may have gone

out of use for burial, they could have continued to be

used for prayer.3

Ólafur Halldórsson (2001:44), because he dated

the settlement of Greenland to ca. AD 1000 rather

than the more traditional date of ca. AD 985, has

suggested that Greenland was never pagan, assuming

that all Icelanders after the “offi cial” date of AD

calibrated ranges of AD 894–996, 909–1017, and

995–1043 (similarly accurate to only one sigma)

nevertheless suggest Christian burial at an early

date, though whether they allow us to distinguish

with certainty between the late tenth century and

the early or late eleventh —a crucial distinction—is

unclear. Niels Lynnerup (1998:48) has noted that a

peak in the calibration curve of these samples makes

for “rather large uncertainties in [the] datings when

… translated to years AD.”

More churches have been identifi ed with the

early period of settlement by other means. A number

of structures with circular banks, such as a small

building surrounded by burials inside an enclosure

at Inoqquassat (Ø 64) (Vebæk 1991:9), very like

the small church at Qassiarsuk, were recorded close

to farms by C.L. Vebæk (1991:7–19) and Knud

Krogh (1967:90–1, 1982:121–3). Although Vebæk

conducted small exploratory investigations, none of

these sites has been properly excavated. One recent

survey of the core area of the Eastern Settlement,

centered on modern-day Qassiarsuk, has identifi ed

at least 2 potential parallels to its turf church (at

Ruin groups 522 and 529 [Ø 33 and 35], Qorlortoq

and Qorlortup Itinnera; Fig. 5), as well as several

Figure 4. Plan of the small church and surrounding cemetery excavated in Ø29a, Qassiarsuk by Knud Krogh in 1962–65.

N

60 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Figure 6. Plan of the church

in Ø1, Nunataaq, inside a

rectangular churchyard.

From Guldager et al.

(2001: 89), reproduced with

kind permission from the

authors.

Figure 5. Plan of the small church in Ø33, Qorlortoq. From Guldager et al. (2001:47), reproduced with kind permission

from the authors.

2009 L. Abrams 61

be seen as historical fact. Equally, the recognition

of the force of paganism in Greenland in this tradition

might derive from a sense of narrative balance,

or from reality, preserving a memory of religious

diversity among the early settlers.

Women’s religious leadership and households

that encompass different religious practices are both

conventional tropes and credible circumstances.

Laws of a seventh-century king of Kent, Wihtred,

name the penalty for a man who sacrifi ces to devils

without his wife’s knowledge (ch. 12; Attenborough

1963:26–27). While Thjodhild is a classic representative

of independent-minded Viking-Age womanhood,

she would nevertheless not be out of place

in the most conventional of ecclesiastical sources.

Women loom large in missionary narratives like

Bede’s, where they bring conversion to men who are

slower to appreciate its value. Bede included in his

Historia a letter from Pope Boniface V to Æthelburh,

the Christian queen of Northumbria (ii.11; Colgrave

and Mynors:172–175). Æthelburh’s “illustrious husband,”

King Edwin, was “still serving abominable

idols and hesitat[ing] to hear and obey the words of

the preachers.” But Æthelburh was urged to “soften

his hard heart as soon as possible.” The pope makes

much of the Scriptural text “the unbelieving husband

shall be saved by the believing wife” (I Corinthians

7:14). The court of Edwin and Æthelburh

encompassed two religious traditions at one time,

as did that of Clovis and Chlothild in Merovingian

Francia in Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks

(II. 28–31; Thorpe 1974:141–5), and many more. It

is diffi cult to say whether there are any hard facts in

this convention; nor is it clear whether it could have

fi ltered down through historical writing to infl uence

the composition of vernacular sagas in medieval

Iceland.

Religious Diversity

If the sagas’ interest in the practical problems of

religious diversity preserved a memory of Greenland’s

past, Iceland’s example should, of course,

cast doubt on any suggestion that such a situation

could have been viable for long. Thorgeir the Lawspeaker’s

eloquent set-piece in Íslendingabók is

based on the logic that pagans and Christians could

not continue to live together in one society (ch. 7;

Grønlie 2006:9, Hermannsson 1930:53). But Ari’s

goal was the writing of Iceland’s past as Christian

history. Furthermore, there were reasons for Greenland

to have been different from Iceland. As we have

seen, the coercive external forces that were instrumental

in conversions elsewhere may not have been

present; and, internally, Greenland may have had a

more horizontal society, lacking the concentration

of prestige and status in a few families which could

999 were Christian. If this itself seems doubtful (see

Vésteinsson 2000 for the complexity of the situation

in Iceland in the eleventh century), it is nonetheless

perfectly credible that some of the settlers who went

to Greenland could have been Christian. Íslendingabók

claims that a missionary presence contributed

to the presence of committed Christians in Iceland

before AD 999 (ch. 7). Thanks to prolonged contact

with the Christian world, increasing Scandinavian

settlement within it, and the rise of Christianity in

the homelands, individual Icelanders could also

have converted abroad—that Leif Eiriksson became

a Christian at the court of Olaf Tryggvason is probably

more plausible than his subsequent missionary

career. Some early settlers may have come from

a Hiberno-Scandinavian milieu. Christian Keller

(1991:134) has raised the possibility that the characteristic

round churchyard of the turf churches refl ects

an infl uence from Celtic Britain. The later identifi cation

of some of those who emigrated to or visited

Greenland as Christian, such as the unnamed poet

from the Hebrides whose verses are cited in Grænlendinga

saga (ch. 2) or Thorbjorn Vifi lsson (one

generation away from a freed slave from the British

Isles; Eiríks saga chs. 1 and 4), could, whether based

on real people or fi ctional stereotypes, realistically

refl ect a combination of religious infl uences in the

new community right from the start.

It is diffi cult to know how to treat the literary

traditions of conversion. The sagas show a particular

interest in religious oppositions. Gudrid’s dramatic

dilemma in Eiríks saga (ch. 4)—whether to help

the community by performing the pagan rituals or

remain true to her Christianity—is one; Thjodhild’s

refusal of conjugal rights is another. Pre- and postconversion

attitudes also confront one another in the

complaints of Thorsteinn Eiriksson’s ghost: “it is a

bad custom, as has been done in Greenland since

Christianity came here, to bury people in unconsecrated

ground with scarcely any funeral rites. I want

to be taken to church, along with the other people

who have died here” (Eiríks saga ch. 6). The statement

in Grænlendinga saga (ch. 5) that Eirik died

before Greenland was converted implies an event

other than the baptism of his wife and children,

which he so manifestly survived. While refl ecting

the Christian insistence on the progression from one

religion to another, it might simply be a literary conceit:

Eirik stood for the old religion and had to die

before the new one could be thought to fl ourish. As

ever with sagas, what you take from the text depends

on your views on the issue of historicity. The accepted

pattern of saga-narrative, necessitated by Iceland’s

own history, was that pagan origins must be

shown to give way to a Christian society—a literary

explanation of the course of events. Alternatively,

Eirik’s paganism and his family’s conversion can

62 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

for ensuring social uniformity, there may have been

no impetus for change. We might wonder whether

a domestic religion might have been more tolerant

than any public one, to which everyone had to conform.

Though its progress in Greenland is obscure,

a primarily domestic religion may have allowed

more fl exible religious conditions to exist before

the development of a more conventional bishop-led

culture. As ecclesiastical organization encroached

on family custom, a more public Christianity— the

religion of society, not the household—won out over

the private context. This process occurred throughout

Christendom, at a pace determined by the nature

of local secular power. Perhaps archaeology can give

us an idea of what percentage of Greenland’s early

farms had these private churches, and what proportion

of the population could have been baptized and

buried there.

Development of an Institutional Church

Although there were churches in early Greenland,

without a bishop there could be no Church.

Conditions had to be right to welcome a bishop,

and resources had to be found for a substantial farm

dedicated to his and his community’s livelihood.

Greenland acquired its fi rst bishop some time in

the twelfth century, probably the 1120s (the date is

problematic; see Arneborg 1991:144). Einars þáttr

Sokkasonar, composed perhaps around AD 1200

and surviving in Flateyjarbók, a manuscript of the

late fourteenth century, makes the initiative emanate

from Brattahlid and from a family which “stood

head and shoulders above other men” (Halldórsson

1981:103–116, Jones 1964:191–203). The story

offers no explanation of why Greenlanders did not

turn to the Icelandic Church for a bishop. Instead,

Einar went to Norway and requested one from King

Sigurd Jórsalafari (AD 1103–1130), after which

Arnald was consecrated by Archbishop Asser in

Lund. However, the Icelandic annals, mostly written

in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries,

record as bishop before Arnald the Icelander Eirik

upsi Gnupsson, who went out to look for Vinland in

AD 1121 or 1123 (Arneborg 1991:143–144; Storm

1888:19, 59, 112, 252, 320, 473). This bishop remains

a mystery. While he makes an appearance on

the infamous Vinland map (Seaver 2004:4–8), he

does not fi gure in any other context. If he existed, he

may have had more of a missionary than an institutional

brief.

Bishop Arnald himself is a shadowy figure, and

some doubt whether he ever left home to take up

his post; although the Icelandic annals record a succession

of appointments, Arneborg (1991:145) has

suggested that Helgi, who arrived in Greenland in

AD 1212, might have been the first resident bishop

have swung the balance in the Christian direction

in the way that the Haukdælir promoted and monopolized

episcopal power in Iceland (Vésteinsson

2000:19–37, 144–161). Thomas McGovern (1992)

has suggested that Greenland was unique in other

ways. He proposed that its society was characterized

more by interdependence than independence and

could have successfully functioned only with an unusual

degree of social and economic co-ordination.

It is possible that, thanks to its distinctive circumstances,

relations between social groups might not

have been articulated in the same way in Greenland

as elsewhere in Christendom, and this would have

had consequences for religious life.

Perhaps the small farm-churches hold the key

to understanding early practice. Whatever rituals

existed in pagan society seem to have included the

dead in the world of the living, and some responsibility

for their aftercare devolved on those who

continued to live in the world. Conversion on its own

seems not to have fundamentally altered this ownership

of the dead. The archaeology of Greenland’s

farm-churches confi rms the claim in Eiríks saga that

household religion, and most specifi cally burial by

family members, continued even after the introduction

of Christianity. The appearance of concerns

about burial in Eiriks saga might be an indication of

thirteenth-century pressures as much as those of the

initial settlement-period; in the absence of suffi cient

excavated data, it is impossible to say when burial

in the larger churches became expected practice. In

western European society, burial was traditionally

the responsibility of the family until the institutional

Church succeeded in monopolizing funerary practice,

breaking up old patterns of authority and allegiance

and replacing them with new ones (Blair

2005:58–65, 228–245, 463–471). Greenland’s small

churches may have been the cult sites of a domestic

religion, private establishments for the farmer and

his household, as opposed to the larger cult buildings

later established by the institutional Church.

We might envisage a privatized religion, serviced

by priests who lived at the farm (or were shared

by several communities, or travelled occasionally

from Iceland). This kind of religious practice could

have allowed for greater diversity in the community

than was “normal” elsewhere. A small number of

Christian farmers with private churches in an otherwise

traditional and conservative society may have

existed for some time without disturbing the social

balance, just as a number of pagan farmers could

have carried on their domestic religion without opposition.

As long as Christianity belonged primarily

to the society of slaves and women— the politically

incompetent—or to a small number of dispersed

farmers (as in Iceland before AD 999?), it might not

have threatened others, and, without mechanisms

2009 L. Abrams 63

perhaps as a way of retaining an identity associated

with where they came from; conservative societies

resist change and cling to traditions that others have

abandoned. McGovern (1992:223–224) has argued

that throughout its existence, the Greenland settlement

was “different, unusual, and extreme by the

standards of contemporary Scandinavia.” It would

be interesting to allow at least the possibility that

until the arrival of a bishop, the religious life of

the settlement was different as well, preserving the

conditions that allowed an “extended dialogue” between

two religious traditions to continue for some

time, until Christianity fi nally carried the day. Once

the bishop arrived, Greenland became more like

everywhere else in the Christian world. This suggestion

may be as inaccurate and tendentious as Bede’s

picture of instantaneous transformation. However,

without more evidence, we can only entertain possibilities

about what the past might have been like.

Literature Cited

Abrams, L. 1995a. The Anglo-Saxons and the Christianization

of Scandinavia. Anglo-Saxon England

24:213–49.

Abrams, L. 1995b. Eleventh-century missions and the

early stages of ecclesiastical organisation in Scandinavia.

Anglo-Norman Studies 17:21–40.

Andersson, T.M. 2003. The Saga of Olaf Tryggvason.

Oddr Snorrason. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY,

USA and London, UK.

Arneborg, J. 1991. The Roman Church in Norse Greenland.

Pp. 142–150, In F. Bigelow (Ed.). The Norse of

the North Atlantic. Acta Archaeologica 61.

Arneborg, J. 2000. Greenland and Europe. Pp. 304–317,

In W.W. Fitzhugh and E.I. Ward (Eds). North Atlantic

Saga. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC,

USA and London, UK.

Arneborg, J. 2001. The Norse settlement in Greenland:

The initial period in written sources and archaeology.

Pp. 12–33, in A. Wawn and Þ. Sigurðardóttir (Eds).

Approaches to Vínland. Sigurður Nordal Institute,

Reykjavík, Iceland.

Arneborg, J. No date. Saga Trails. Brattahlið, Garðar,

Hvalsey Fjord’s Church and Herjolfsnes: Four

chieftain’s farmsteads in the Norse settlements of

Greenland—A visitor’s guidebook. National Museum

of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Arneborg, J., et al. 1999. Change of diet of the Greenland

Vikings determined from stable carbon isotope

analysis and C14 dating of their bones. Radiocarbon

41(2):157–168.

Attenborough, F.L. 1963. The Laws of the Earliest English

Kings. Russell and Russell, New York, NY, USA.

Bagge, S. 2006. The making of a missionary king: The

medieval accounts of Olaf Tryggvason and the Conversion

of Norway. Journal of English and Germanic

Philology 105:473–513.

Benediktsson, J. 1968. Íslendingabók. Landnámabók.

Íslensk fornrit 1, Reykjavík, Iceland.

Benedikz, B. 1976. Bede in the Uttermost North. Pp.

(Storm 1888). Absenteeism was not unprecedented:

a number of Hamburg-Bremen’s tenth- and eleventh-

century appointments to Denmark and Sweden

seem never to have visited their sees (Sawyer

1987:78–79, 93). Scholars disagree about whether

Greenlanders themselves gained in power or lost it

once the institutional Church arrived in Greenland,

that is, whether the Church was an exploitative

colonial force or an opportunity for domestic success.

Arneborg (1991) and Keller (1991) have

argued (contra McGovern, i.e., 1992:220–4) that

the Church never really dominated the chieftains,

who maintained their independence in cultural, political,

and economic terms. But it is interesting that

Greenland never produced its own bishops. On the

Icelandic model, Einar or a son of the family should

have become the first bishop, harnessing familylands

to institutional power. Instead, Greenland’s

first official bishop seems to have been a Norwegian,

appointed by the archbishopric in Lund, and

subsequent bishops continued the association with

Norway. A lack of homegrown enthusiasm for the

Church, a lack of wealth, an inadequate educational

infrastructure, or an insufficiently hierarchical society

without the right kind of elite could explain

this reliance on outsiders. Although, as Keller

(1991:128–137) has pointed out, Norwegian kings

could hardly have taken responsibility for the

operation of the Church in Greenland before AD

1261, Norwegian royal power or trade relationships

could in some way have played a role in putting

Greenland’s bishops in post before the settlement

officially came under Norwegian rule. Under the

bishops’ influence, Greenland may have become

more Norwegian. Once Christian scrutiny and pressure

to conform were more immediate, Greenland

would certainly have become more conventionally

Christian, with Christian practice penetrating more

fully into social norms. Any leeway in religious

identity would have been unlikely to survive the

direct surveillance and institutional pressure of a

resident bishop.

Conclusion

We know very little about the earliest Christianity

in Greenland. You could say, however, that if

we had more abundant written sources, we might

be no better informed. History and anthropology

both show how the record of conversion can mask

its reality. Archaeology’s information on early

churches and burials is therefore crucial, and more

data could radically alter our picture. Although

Christian convention required conversion to be rapid

and complete, we should consider whether some of

the settlers in Greenland might have in fact stuck to

their pagan ways for longer than has been assumed,

64 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Krogh, K.J. 1982. Erik den Rødes Grønland. Nationalsmuseets

Forlag, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Lynnerup, N. 1998. The Greenland Norse. A biologicalanthropological

study. Meddelelser om Grønland,

Man and Society 24.

Magnusson, M., and H. Pálsson. 1960. Njal’s Saga. Penguin

Books, London, UK.

Magnusson, M., and H. Pálsson. 1965. The Vinland Sagas.

The Norse Discovery of America. Penguin Books,

London, UK.

Maxwell, D. 1999. Christians and Chiefs in Zimbabwe. A

Social History of the Hwesa People c. 1870s–1990s.

Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, UK.

McGovern, T.M. 1992. Bones, buildings, and boundaries:

Palaeoeconomic approaches to Norse Greenland. Pp.

193–106, In C.D. Morris and D.J. Rackham (Eds).

Norse and Later Settlement and Subsistence in the

North Atlantic. University of Glasgow, Department of

Archaeology, Glasglow, Scotland, UK.

Phelpstead, C. 2006. Pilgrims, missionaries, and martyrs:

The holy in Bede, Orkneyinga saga, and Knýtlinga

saga. Pp. 53–81, In L.B. Mortensen (Ed.). The Making

of Christian Myths in the Periphery of Latin Christendom

(c. 1000–1300). Museum Tusculanum Press,

Copenhagen, Denmark.

Sawyer, B., et al. 1987. The Christianization of Scandinavia.

Viktoria Bokförlag, Alingsås, Sweden.

Schmeidler, B. 1917. Adam von Bremen, Hamburgische

Kirchengeschichte. Hannsche Buchhandlung, Hannover

and Leipzig, Germany.

Schmeidler, B. 1918. Hamburg-Bremen und Nordost-

Europa. Dieterich’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung m.b.H.,

Leipzig, Germany.

Seaver, K.A. 2004. Maps, Myths, and Men. The Story of

the Vinland Map. Stanford University Press, Stanford,

USA.

Stoklund, M. 1993. Objects with runic inscriptions from Ø

17a in Narsaq—A Norse Landnáma farm. Pp. 47–52,

In C.L. Vebæk et al. (Eds.). Meddelelser om Grønland,

Man and Society 18.

Storm, G. 1888. Islandske Annaler. Grøndal and Søns

Bogtrykkeri, Christiania, Norway.

Stummann Hansen, S., and J. Sheehan. 2006. Bønhústoftin

and the early Christianity of the Faroe Islands, and

beyond. Archaeologica Islandica 5:27–54.

Sveinsson, E.Ó. 1954. Brennu-Njáls saga. Íslensk fornrit

12, Reykjavík, Iceland.

Sveinsson, E.Ó., and M. Þórðarson. 1935. Eyrbyggja saga.

Íslensk fornrit 4, Reykjavík, Iceland.

Thorpe, L. 1974. Gregory of Tours. History of the Franks.

Penguin Books, London, UK.

Tschan, F.J., and T. Reuter. 2002. History of the Archbishops

of Hamburg-Bremen. Revised Edition. Columbia

University Press, New York, NY, USA.

Turville-Petre, G. 1972. Legends of England in Icelandic

manuscripts. Pp. 104–21, In P. Clemoes (Ed.). The

Anglo-Saxons. Studies in Some Aspects of their History

Presented to Bruce Dickins. Bowes and Bowes,

London, UK.

Vebæk, C.L. 1991. The Church Topography of the Eastern

Settlement and the Excavation of the Benedictine Convent

in Uunartoq Fjord. Meddelelser om Grønland,

Man and Society 14.

334–43, In G. Bonner (Ed.). Famulus Christi. Essays

in Commemoration of the Thirteenth Centenary of the

Birth of the Venerable Bede. SPCK, London, UK.

Blair, J. 2005. The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford

University Press, Oxford, UK.

Christensen, A.E. 1976. Archbishop Asser, the emperor

and the pope. The fi rst archbishop of Lund and his

struggle for the independence of the Nordic Church.

Scandinavian Journal of History 1:25–42

Colgrave, B., and R.A.B. Mynors, 1969. Bede’s Ecclesiastical

History of the English People. Clarendon Press,

Oxford, UK.

Crawford, B.E. 1983. Birsay and the early earls and bishops

of Orkney. Pp. 97–118, In W.P.L. Thomson (Ed.).

Birsay. A Cultural and Political and Ecclesiastical

Power. Orkney Heritage 2. Kirkwall, Orkney, UK.

Curschmann, F. 1909. Die Älteren Papsturkunden des

Erzbistums Hamburg. Leopold Voss, Hamburg and

Leipzig, Germany.

Ekrem, I., and L.B. Mortensen. 2003. Historia Norwegie.

Museum Tusculanum Press, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Eldjárn, K., and A. Friðriksson. 2000. Kuml og Haugfé.

Úr heiðnum sið á Íslandi. 2nd Edition. Mál og menning,

Reykjavík, Iceland.

Gelting, M.H. 2004. Elusive bishops: Remembering,

forgetting, and remaking the history of the early Danish

Church. Pp. 169–200, In S. Gilsdorf (Ed.). The

Bishop: Power and Piety in the First Millennium. LIT,

Münster, Germany.

Grønlie, S. 2006. Íslendingabók. Kristni Saga. The Book

of the Icelanders. The Story of the Conversion. Viking

Society for Northern Research, London, UK.

Guldager, O., S. Stummann Hansen, and S. Gleie. 2002.

Medieval Farmsteads in Greenland. The Brattahlid

Region 1999–2000. Danish Polar Centre, Copenhagen,

Denmark.

Halldórsson, Ó. 1978. Grænland í miðaldaritum. Sögufélag,

Reykjavík, Iceland.

Halldórsson, Ó. 1981. The conversion of Greenland in

written sources. Pp. 203–216, In H. Bekker-Nielsen,

et al. (Eds). Proceedings of the 8th Viking Congress.

Odense University Press, Odense, Denmark.

Halldórsson, Ó. 2001. The Vinland sagas. Pp. 39–51, In A.

Wawn and Þ. Sigurðardóttir (Eds). Approaches to Vínland.

Sigurður Nordal Institute, Reykjavík, Iceland.

Hastings, A. 1994. The Church in Africa 1450–1950. Clarendon

Press, Oxford, UK.

Hollander, L.M. 1964. Heimskringla. History of the

Kings of Norway. University of Texas Press, Austin,

TX, USA.

Jones, G. 1964. The Norse Atlantic Saga. Oxford University

Press, London, UK.

Jónsson, F. 1932. Saga Óláfs Tryggvasonar. G.E.C. Gads

Forlag, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Karras, R.M. 1997. God and man in medieval Scandinavia.

Writing—and gendering—the conversion. Pp.

100–114, In J. Muldoon (Ed.). Varieties of Religious

Conversion in the Middle Ages. University Press of

Florida. Gainesville, FL, USA.

Keller, C. 1991. Vikings in the West Atlantic: A model

of Norse Greenlandic Medieval Society. Pp. 126–41,

In F. Bigelow (Ed.). The Norse of the North Atlantic.

Acta Archaeologica 61.

Krogh, K.J. 1967. Viking Greenland. National Museum,

Copenhagen, Denmark.

2009 L. Abrams 65

Vésteinsson, O. 2000. The Christianization of Iceland.

Priests, Power, and Social Change 1000–1300. Oxford

University Press, Oxford, UK.

Vésteinsson, O. 2005. The formative stage of the Icelandic

Church c. 990–1240 AD. Pp. 71–81, In H. Þorlaksson

(Ed.). Church Centres: Church Centres in Iceland from

the 11th to the 13th Century and their Parallels in Other

Countries. Snorrastofa, Reykholt, Iceland.

Vohra, P. 2008. The Eiríksynnir in Vínland: Family exploration

or family myth? Viking and Medieval Scandinavia

4:249–267.

Wahlgren, E. 1993. Vinland sagas. Pp. 704–5, In P. Pulsiano

(Ed.). Medieval Scandinavia. Garland, NY, USA

and London, UK.

Wood, S. 2006. The Proprietary Church in the Medieval

West. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Endnotes

1I should like to thank Judith Jesch and Rie Oldenburg for

information on the Narsaq rune-stick.

2I am grateful to Jette Arneborg for information on the

dates from Qassiarsuk and Kilaarsarfi k, and to Marc Pollard

of the Oxford Research Laboratory for Archaeology

and the History of Art for discussion of C14 methodology.

3I am grateful to Steffen Stummann Hansen and Christian

Keller for discussion of these sites; I owe this last suggestion

to Christian Keller.