114 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Introduction

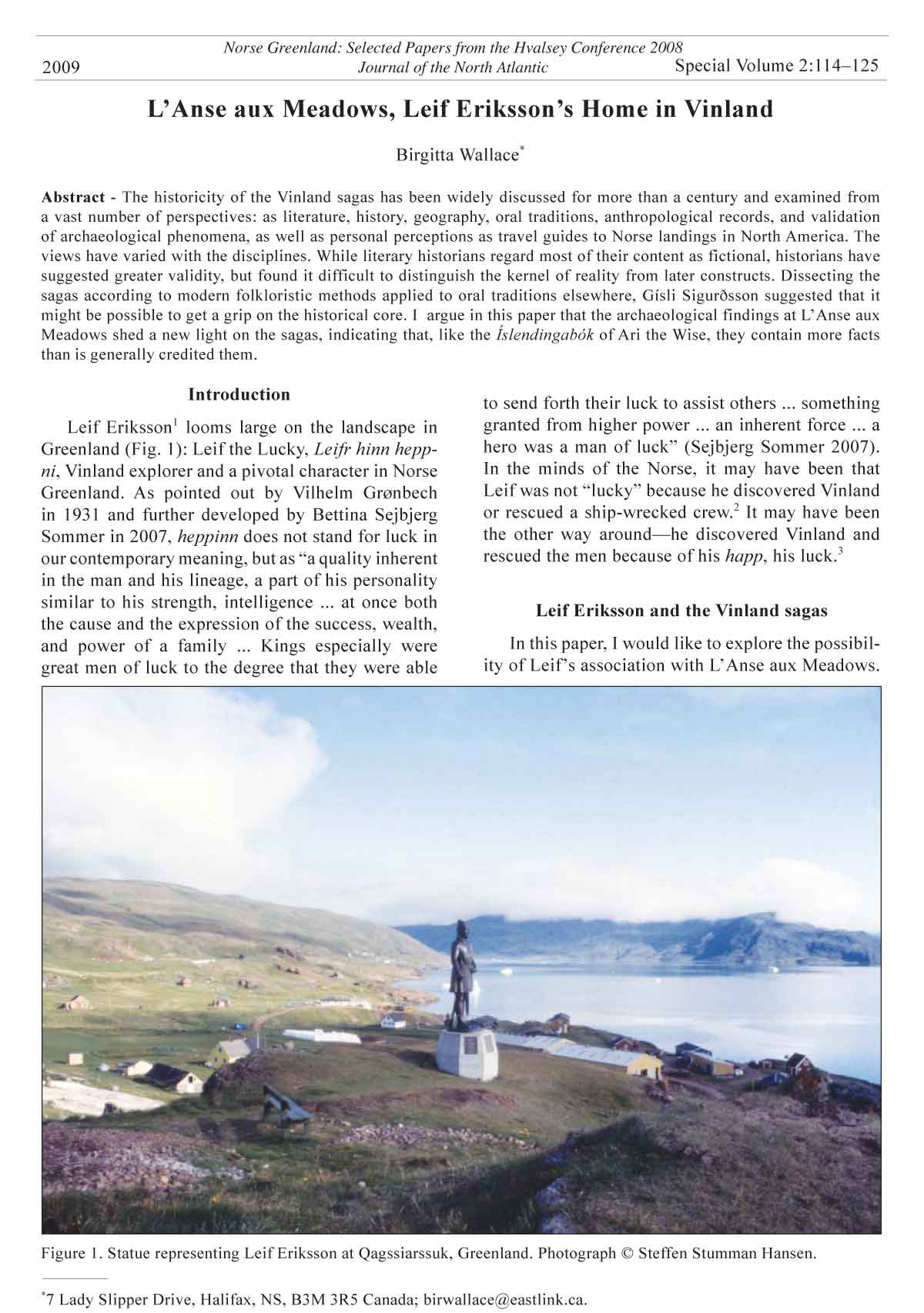

Leif Eriksson1 looms large on the landscape in

Greenland (Fig. 1): Leif the Lucky, Leifr hinn heppni,

Vinland explorer and a pivotal character in Norse

Greenland. As pointed out by Vilhelm Grønbech

in 1931 and further developed by Bettina Sejbjerg

Sommer in 2007, heppinn does not stand for luck in

our contemporary meaning, but as “a quality inherent

in the man and his lineage, a part of his personality

similar to his strength, intelligence ... at once both

the cause and the expression of the success, wealth,

and power of a family ... Kings especially were

great men of luck to the degree that they were able

to send forth their luck to assist others ... something

granted from higher power ... an inherent force ... a

hero was a man of luck” (Sejbjerg Sommer 2007).

In the minds of the Norse, it may have been that

Leif was not “lucky” because he discovered Vinland

or rescued a ship-wrecked crew.2 It may have been

the other way around—he discovered Vinland and

rescued the men because of his happ, his luck.3

Leif Eriksson and the Vinland sagas

In this paper, I would like to explore the possibility

of Leif’s association with L’Anse aux Meadows.

L’Anse aux Meadows, Leif Eriksson’s Home in Vinland

Birgitta Wallace*

Abstract - The historicity of the Vinland sagas has been widely discussed for more than a century and examined from

a vast number of perspectives: as literature, history, geography, oral traditions, anthropological records, and validation

of archaeological phenomena, as well as personal perceptions as travel guides to Norse landings in North America. The

views have varied with the disciplines. While literary historians regard most of their content as fictional, historians have

suggested greater validity, but found it difficult to distinguish the kernel of reality from later constructs. Dissecting the

sagas according to modern folkloristic methods applied to oral traditions elsewhere, Gísli Sigurðsson suggested that it

might be possible to get a grip on the historical core. I argue in this paper that the archaeological findings at L’Anse aux

Meadows shed a new light on the sagas, indicating that, like the Íslendingabók of Ari the Wise, they contain more facts

than is generally credited them.

2009 Special Volume 2:114–125

Norse Greenland: Selected Papers from the Hvalsey Conference 2008

Journal of the North Atlantic

*7 Lady Slipper Drive, Halifax, NS, B3M 3R5 Canada; birwallace@eastlink.ca.

Figure 1. Statue representing Leif Eriksson at Qagssiarssuk, Greenland. Photograph © Steffen Stumman Hansen.

2009 B. Wallace 115

This is not an exercise of looking at archaeology

through the lens of the Vinland sagas. On the contrary,

it is looking at the Vinland sagas through the

spyglass of archaeology. The importance of the archaeological

data in understanding written descriptions

by Europeans of Aboriginal cultures has been

emphasized by Bruce Trigger:

Growing awareness of historical and archaeological

data reveals that ... the archaeological data

provide potentially the most comprehensive and

continuous source of information about the past

and hence, contrary to what has been believed,

constitute the basic framework to which other data

must be related (Trigger 1982:151).

It is fair to say that the discovery of L’Anse

aux Meadows was inspired by the Vinland sagas4

(Ingstad 1960, 1966; Ingstad and Ingstad 1986).

However, the excavation strategy and site interpretation

were not infl uenced by the sagas, either in the

work by the Ingstad expedition or later Parks Canada

team. Once the dating and provenience of the buildings

were clear, the archaeological approach was to

document the economic basis of the site, its place in

the environment, social structure, length of occupation,

and relationship to other cultures on the site.

Only when we had a reasonably clear view of what

the site was all about did the sagas come into play,

with surprising results.

We do not know much about Leif Eriksson.

Beyond the Vinland sagas, he appears only in one

phrase in the Saga of St Olaf. In 1018, when King

Olaf was advised to kill his cousin King Hrærik of

the Oplands, Olaf instead commanded the Icelandic

merchant Thorarinn Nefjolfsson to take him to Leif

Eriksson in Greenland:

Þórarinn segir: “Dýrt er dróttins orð, eða hverja

bæn viltu af mér þiggja?”

Hann segir: “Þá, at þú fl ytir Hrærik til Grænlands

ok færir hann Leifi Eiríkssyni.”

Þórarinn svarar: “Eigi hefi ek komit til Grænlands.”

Konungr segir: “Farmaðr slíkr sem þú ert, þá er þér

nú mál at fara til Grænlands, ef þú hefi r eigi fyrr

komit” (Ólason ed. 1947:96).5

Although the historicity of Leif’s siblings has

been questioned (Perkins 2004:47–48), Leif, like his

father Erik, is widely considered to have been a historical

person. I will here go a step further and present

him as the possible builder of L’Anse aux Meadows.

Before I get to that point, I will delve into the treacherous

seas of the Vinland sagas and the question of their

anchorage in reality. Much of this is a recapitulation

of what I presented several years ago in an article in

Contact, Continuity, and Collapse (Wallace 2003c),

but with elaborations on certain points.

Even more than the Icelandic family sagas, the

Vinland sagas are exciting narratives of discovery,

voyages to far-fl ung shores, and meetings with people

of another ilk. The descriptions are so vivid and the

progression so logical that one is easily seduced into

seeing them as unadulterated truths. They are still

viewed this way by most popular Viking enthusiasts

bent on proving their pet theories of Vinland.

In scholarly circles, mindless acceptance of the

Vinland sagas as historical documents has long

ceased. Many, in fact, view them as little more than

allegorical excursions to a distant paradise (Baumgartner

1993, Nansen 1911). Others have identifi ed

them as exotic tall tales of travel, perhaps with a core

of historical truth, but mostly fi ctitious and a western

parallel to Yngvars saga víðförla (Anderson 2000,

Ólason 2001:60). These writers point to a content

that features fantastic creatures from the medieval

learned world such as unipeds, Scottish runners,

and dreams. Bjarni Herjolfsson, Freydis and her

husband Thorvard, Tyrkir, Thorhall the Hunter,

Helgi, Finnbogi, and the Scottish runners Haki and

Hekja are seen as fi ctional. The two Skræling boys

who tell the Norse about their parents, Vethildr

and Óvægir, and their two kings, Avaldamon and

Avaldidida, are also viewed as inventions. Geraldine

Barnes (2001:30, note 81) and Richard Perkins

(2004:52–53) both see these names as creations patterned

on Leif Eriksson’s mother Þjóðhildr and the

Norse word óvæginn, meaning unyielding or headstrong

(Perkins 2004:52). They also suggest that the

names of the “kings,” Avaldamon and Avaldidida

are based on King Valdemar and Queen Allogia of

Russia (Barnes 2001:30, note 81; Perkins 2004:52).

We may alternatively, however, compare it to the

custom of all later Europeans in North America to

render Aboriginal names into their own sound system.

Atlantic Canada abounds in these: Kejimkujik,

Kouchibouguac, Miramichi, Musquodoboit. Aboriginal

chieftains were often viewed as “kings” by both

the English and French. The boys’ statement that

they lived in caves or holes (pits) also has the ring

of historical truth. Dwellings in the Little Passage

complex (ancestors of the Innu and Beothuk) were

“pit houses”, structures dug into the ground (Pastore

1983:102–107). This kind of house was also used by

the Dorset (McGhee 1978:64).

While many scholars, such as Geraldine Barnes

(2001:xix) and Helgi Þorláksson (2001:75), recognize

a historical core in the Vinland sagas, in their

views, it will never be possible to sort out what is

historically correct. Vinland’s geographical location

can never be established with certainty (Barnes

2001:xix), an opinion also expressed by Vésteinn

Ólason (2001).

Gísli Sigurðsson, in his precedent-setting The

Medieval Icelandic Saga and Oral Tradition

(Sigurðsson 2004) argues that both Grænlendinga

saga and Eiríks saga rauða must be looked upon as

116 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

text-based oral traditions. Only when we understand

the essence of oral traditions, can we begin to sort

out what may be the historical core. As long as the

traditions remained oral, they were in a constant

state of fl ux, changing from one recitation to another

according to the audience and occasion. Old material

was mixed with new and subject to the interests of

those in control—or what was topical at that particular

moment. A well-known parallel is the Roskilde

ship barrier, which oral tradition associated with

Queen Margrethe because her fame eclipsed earlier

events to which it was actually related (Olsen and

Crumlin-Pedersen 1969:9).

Gísli Sigurðsson also cites the studies by John

Miles Foley (Foley 1991), which propose that oral

traditions are founded on formulas and existing

themes and that each episode must be seen in light

of the tradition as a whole. There is no need to spell

out everything because the audience is already familiar

with the events and characters. Mere hints and

allusions suffi ce. For the same reason, stories are not

told from beginning to end. What Carol Clover has

called “the immanent whole” (Clover 1986) already

exists in the mind of the audience.

Sigurðsson has used some of his theories on the

Vinland sagas. In the case of Grænlendinga saga and

Eiríks saga rauða, he fi nds it clear that both stem

from the same oral source. Both have been adapted

to fi t the audience and the situation prevalent when

they were locked into written texts. Gísli’s work

takes us a long way in separating truth from lore.

Adding insight gained from archaeology, we can go

one step farther. Archaeology provides the physical

world of the saga texts, the “immanent whole” of the

Vinland sagas, the material world in which the sagas

were produced. Leaving out the archaeological

evidence from the Vinland sagas can lead writers

far afi eld. One example is the scene in Grænlendinga

saga where native people approach the Norse

“with loads of furs for trading purposes, without any

previous visit of inspection on their part,” which

leads Erik Wahlgren (1969:70) to consider it a late

interpolation. Archaeology has shown that trade was

extensive in pre-European North America and some

of it involved fur (e.g., Spiess 1987–88:21). For

instance, one trade route ran from present-day Bay

of Chaleur via rivers and portage to Notre-Damedu-

Portage on the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. It

is therefore not surprising that the Norse would run

into such a trading party.

Understanding anthropological concepts such as

migration also helps to understand the reality of the

10th and 11th centuries. Many writers coming from the

literary tradition fi nd it unacceptable that there is a

fi fteen-year gap between the presumed sighting of the

North American coast and the fi rst planned expedition

there. They read this as typical literary symbolism,

and see Bjarni’s inaction as a foil for the determined

actions of Leif (Perkins 2004:47, Wahlgren 1969:44).

On the contrary, the time that elapsed before the new

coasts could be explored carries the ring of historical

truth. A colony is not created overnight. Housing has

to be built, lands cleared for pasture, and livestock

has to be increased in order to provide suffi cient

sustenance. At the same time, the unfamiliar local

environment has to be explored and its resources investigated,

and archaeological investigations are now

beginning to document the various steps (Vésteinsson

1998, Vésteinsson et al. 2002). Developing further

settlement and freeing up labor for new enterprises

takes time, especially in a hitherto uninhabited area.

As stated by David Anthony, settlement is a process,

not an event (Anthony 1990).

What do the Vinland sagas really tell us?

With the above considerations in mind, we can

distinguish some of the meanings hidden in the

sagas. One is the type of voyages portrayed. Everyone

has taken for granted that the Vinland voyages

were a colonizing venture. This is probably because

the Norse settlement progression seems so logical:

from Norway to the British Isles, the Faroes, Iceland,

and Greenland. However, reaching Greenland,

the Norse expansion had burnt out. If Niels

Lynnerup’s (1998:115, 2003) fi gures are correct,

Greenland’s initial settlement had only 400–500 inhabitants

and never grew to more than 2500 (Lynnerup

2003:142). This is in sharp contrast to Iceland,

where the initial settlement numbered in the thousands

(Vésteinsson 1998:26–27), later growing up

to at least 40,000 (Stefánsson 1993:312), possibly

even 70,000 (Lynnerup 2003:142). Greenland had

reached a limit where further splintering was impossible.

A handful of families cannot colonize a new

continent. They cannot exist in isolation. Hundreds

of people are needed to start a colony (McGovern

1981); in other words, the whole Greenland colony

would have had to participate. Nor was there any

population pressure in Greenland at this time. There

was plenty of land, and the elite, the only ones with

means to organize expeditions, already had the best

lands (Keller 1991), so further colonies were not

likely on their agenda.

On the other hand, the resources in the western

new lands would have been of considerable interest

(Figs. 2 and 3). If one analyses the Vinland sagas,

it is obvious that they do not describe colonization,

but exploration for resources and their subsequent

exploitation (Grænlendinga saga, Smiley

2000:642).6 The profi t motivation is clearly stated

in both sagas. Lumber formed the major part of the

goods brought back to Greenland. Colonization may

have been considered a future possibility,7 but, for

the moment, settlement consisted simply of a base

2009 B. Wallace 117

for the collection and transhipment of resources.

This scenario also has the mark of reality. It adheres

to a nearly universal model for the fi rst stage of emigration

into new areas where resources are exploited

by the parent community (Anthony 1990).

Another fact indicating exploration and exploitation

rather than colonization is that the sagas do not

tell of farming families settling in, but of labor crews

contracted separately for each voyage. Leif Eriksson

was fi rst in charge, as his father’s agent. After Erik’s

death, when Leif succeeded him as chieftain, the expeditions

were led by other members of the family,

but the control still remained with Leif. This effort is a

clear core-area control over a distant resource emporium.

The leaders could have merchant partners with

whom they shared the profi ts. The crews were mostly

men who could put in days of hard

labor.8 A few women were along for female

chores such as cooking, cleaning,

and maintenance of clothes. There were

also members of the leader’s personal

staff, such as Thorhall the Hunter, and

slaves such as the German Tyrkir. Some

scholars regarding the sagas from a

literary point of view tend to think of

these saga fi gures as literary concepts.

Richard Perkins suggests that Thorhall

is an invention by the saga author to

serve as a mouthpiece for two verses

which probably are not part of the

original saga (Perkins 2004:51). This

interpretation is entirely possible, but

the men required for a venture such as

the Vinland voyages would have had to

possess the qualities attributed to Thorhall:

a hunter, skilled in many tasks,

trusted by Erik, and experienced in life

in uninhabited regions (í óbyggðum)

(Eiríks saga rauða, Smiley 2000:666).

Halldór Hermannsson (1954) has suggested

that the very appellation fóstri,

foster father, indicates that Tyrkir is

a fi ctional fi gure. Hermann Pálsson

agrees with him and thinks that Tyrkir

was invented simply to give credence

to the grapes found (Hermann Pálsson

“Vínland Revisited 31”—cited in

Vésteinn Ólason 2001:53, note 27).

Richard Perkins (2004:48) concurs

and adds that the name Tyrkir is a literary

fi ction created as an allusion to

southerly foreigners such as Turks. I

would argue that Tyrkir was more likely

a slave, as fóstri could also refer to a

domestic slave, a slave who has worked

in the house and among whose chores

it was to take care of the children.9 This

interpretation would fit the context

as well as the German origin. Slaves

are likely to have been brought for the

many heavy tasks associated with the

construction of a new establishment.

The lack of genealogies in Grænlendinga

saga has also been seen as a

sign of invention (Barnes 2001:32–33,

Figure 2. The eastern shore of New Brunswick is characterized by long

sandbars, lagoons, locally known as barrachoix, large hardwood forests,

and the mighty rivers Miramichi and Restigouche. Air photograph © André

Dufresne, courtesy Kouchibouguac National Park, Parks Canada Agency; all

others © Rob Ferguson.

Figure 3. The riches of Vinland: New Brunswick wild grapes, and grape wines

on a tree, vínvíð; fi eld of Elymus mollis. Photographs © Kevin Leonard.

118 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Perkins 2004:48–49). Could it not be that the genealogy

of Greenland was of little interest in Iceland at

the time the sagas were recorded? Genealogies serve

to place individuals in their proper social context,

and in Iceland, the Greenland context would have

been of lesser consequence.

Grænlendinga saga tells that as soon as Leif’s

expedition landed, they constructed búðir, or temporary

living quarters with permanent walls and

temporary roofs of cloth. Later, when they decided

to stay the winter, they built large houses (Grænlendinga

saga, The Sagas of Icelanders: 639), at

búask þar um þann vetr, ok gjørðu þar hús mikil

(Reeves 1890:147).10 In Eiríks saga, rauða, búðir,11

and skálar are used interchangeably. No structures

are mentioned for the livestock, only that they did

not need to lay up hay for the winter as the grass did

not wither much and the animals could graze outside.

Again, this scenario is what we would expect

from what we know of the Norse material world.

The logical type of initial housing would have been

búðir, the type of temporary living quarters known

from Thingvellir and Hegranes (Ólafsson and Snæsdóttir

1976). Once the camp was made more or less

permanent, regular hús (a few lines later termed

skálar) are the expected alternative.

L’Anse aux Meadows site

Now let us see what L’Anse aux Meadows was

all about. Many scholars have dismissed L’Anse

aux Meadows as peripheral in the Vinland story

(Kristjánsson 2005:39). I myself held that view for

a long time. I am now contending that L’Anse aux

Meadows is in fact the key to unlocking the Vinland

sagas. Two factors crystallized this idea in my mind.

One was my subsequent research into early French

exploitation outposts in Acadia (Wallace 1999) and

the nature of migration (Anthony 1990). Here we

can see a complete parallel to the Norse efforts in

North America. Exploitation of resources for a parent

country, undertaken by a largely male work force

with no intention of long-term settlement, is the

principle which makes sense of the Vinland Sagas.

The second signal was the identifi cation of butternut

remains in the Norse stratum at L’Anse aux Meadows.

Here was the smoking gun that linked the limited

environment of northern Newfoundland with a

lush environment in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where

wild grapes did indeed exist. The mythical Vinland

had a basis in archaeological fact.

Nature of the site

As specifi ed many times before (Wallace 1991,

2003b, 2003c, 2005), the function of L’Anse aux

Meadows was that of a specialized winter camp,

a base camp for further exploration and a gateway

to resources. Our guides to the location of those

resources are three butternuts or white walnuts, a

North American species, as well as a burl of butternut

wood (Fig. 4). Butternut trees (Fig. 5) have

never grown in Newfoundland.12 The northern limit

for butternuts is New Brunswick, 1000 km south of

L’Anse aux Meadows (Hosie 1979:134).

The signifi cance of the butternuts and the piece

of butternut wood, a burl, was not recognized until

Figure 4. L’Anse aux Meadows butternut and butternut

tree burl. Photograph © Peter Harholdt, courtesy Arctic

Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History.

From Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga, ed. By W.W. Fitzhugh

and E. Ward.

Figure 5. Miramichi butternut trees; inset: butternut husks.

Photographs © Rob Ferguson.

2009 B. Wallace 119

wild in the forest along the rivers and at the time

when they were ripe and ready to be picked.

The signifi cance of the grapes, in myth and reality,

cannot be overstated. Wine was associated with

wealth, power, and vernacular as well as religious

leadership. Ostentatious drinking and feasting ceremonies

were means for exerting power. For a person

such as Leif, a potential unlimited wine supply

would have been a welcome prospect in support of

his chieftainship.

There are several striking aspects of L’Anse aux

Meadows:

Location. The choice of location makes the site

easy to fi nd (Fig. 6).13 The placement of the site close

to a beach on wetlands at the outlet of a stream is in

part a typical situation for the early farms in Iceland

(Vésteinsson 1998:7–8). Yet there is a considerable

difference. The prime early locations in Iceland are

open areas near the estuaries of big rivers as far inland

as there is wetland for pastures associated with

them (Vésteinsson 1998:8). At L’Anse aux Meadows,

the stream issuing into Epaves Bay is too small

for navigation and Epaves Bay is not a good harbor.

14 The coast is one of the most exposed locations

after the wood and the nuts had been treated with

polyglycol acid. Radiocarbon-dating has therefore

not been possible. However, all pieces were very

clearly associated with the Norse stratum; the burl

also had distinct cut marks done with a sharp metal

knife (Gleeson 1979). We examined the possibility

of a DNA study, comparing the nuts to those growing

in New Brunswick today. As the nuts have lost their

“meat”, such an analysis is evidently not possible.

It is noteworthy that butternuts grow in the same

areas as wild grapes, and New Brunswick is in fact

also the northern limit for grapes. Both species ripen at

the same time in September. Thus, L’Anse aux Meadows

is a base for summer excursions to a place far

south with butternut trees and grapes. It fi ts the model

of Straumfjord in the north and Hóp in the south.

The debate whether or not the Norse found wild

grapes has raged for decades. Many believe that the

grapes are more a medieval learned reference to a

mythical paradise, the Insula Fortunata, than a materialistic

fact (Nansen 1911[1]:345). Whether the

grapes helped to lend the concept a paradisical glimmer

or not, the fact is that the occupants of L’Anse

aux Meadows did visit regions where grapes grew

Figure 6. The Strait of Belle Isle. Map © Google Earth.

120 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

ment (Vésteinsson 1998), when cooperation must

have been particularly essential. Such cooperation

would have been equally important at L’Anse aux

Meadows. We can in fact trace it in the artifact

distribution, where the activities of one group seem

to have complemented those of others (Wallace

1991:191, 2003a:176). However, even with these

similarities to Iceland, the L’Anse aux Meadows site

is different. The absence of animal structures is the

most conspicuous aspect. Likewise, the artifacts and

their distribution are not of normal household nature,

but indicate specialized activities such as iron

making and smithing, carpentry, and boat repair.

Social structure. The L’Anse aux Meadows

settlement could accommodate up to 70 to 90 individuals.

This is an unusually high concentration

of people and a proportionally large portion of the

available Greenland work force.

The L’Anse aux Meadows buildings are substantial

houses, three of them halls, meant to be used

year-round. The halls are large. Two are on a par

with what Orri Vésteinsson has classifi ed as middle/

high status, the other as middle status (Vésteinsson

2004:74–75). The largest hall has a fl oor space

of 160 m², on par with Stöng; another has 103 m²,

slightly bigger than Sámsstaðir. The smallest hall

(89 m²) is only slightly smaller than Ísleifsstaðir 2.

These are the types of halls used by the elite. The

largest hall is also the most complex one. It seems

logical to conclude that it was built for the leader of

the expedition and founder of the settlement.

The small house next to one of the large halls is

of low status, the type of cottage found on the outskirts

of large estates and inhabited by farm workers,

subordinate people. The two pit buildings fl anking

halls D and F both have fi replaces. Used for accommodation

or day work, their occupants would also

have been workers of low status. The small, rounded

hut was also a dwelling. Its occupants would have

been on the bottom rung of the social ladder, possibly

slaves. Thus, we are dealing with a socially

stratifi ed site containing leaders with their retinue

and workers of different ranks. The Vinland sagas

outline the same type of ranking.

Size of the site. Basing our fi gures on the construction

of the replica houses at L’Anse aux Meadows, we

estimate that it would have taken 60 men two months

or 90 men one and a half months to build the original

L’Anse aux Meadows settlement.17 This is the better

part of a summer. As outlined elsewhere (Wallace

2005:31), the construction represented a signifi cant

investment. In terms of time and labor, it is unlikely

that the contemporary small Greenland work force

would have repeated this effort.

Ethnic background of the occupants. A few years

ago, lithic analyses, sponsored by the Icelandic

Ministry of Education and Culture, were done by

Kevin Smith (2000) on 9 pieces of jasper fi re strikers

in northern Newfoundland. The fact that the site

faces the Strait and Labrador indicates that access to

or surveillance of the Strait was one of the guiding

factors (Fig. 6). There are plenty of sheltered coves

on the east coast only a few km away, such as Straitsview,

Noddy Bay, and Quirpoon to mention but three

of the closest ones. These coves have much better,

protected harbors.

The economy. The archaeological investigations

included extensive searches for traces of domesticates,

animal shelters, and evidence of cultivation.

There were no structures of any kind for animals. Pollen

analyses (Davis et al.1988, Henningsmoen 1977,

McAndrews and Davis 1978, Mott 1975) revealed

no disturbances in the fl ora normally associated with

grazing, nor any signs of cultivation or introduced

plants.15 The food bones were poorly preserved, but

practically all that could be identifi ed was sea mammal

(seal and whale; Rick 1977). There was also a

single specimen of a very large cod vertebra.

One much discussed scapula, originally identifi ed

in Norway as domestic pig (Rolf Lie in A.S. Ingstad

1977:266), or an indeterminate mammal “the size

of a deer-hound or slightly larger” (H. Olsen in A.S.

Ingstad 1977:267), was later identifi ed as seal by

Anne Rick (1977), Arthur Spiess (1990), and Frances

Stewart (2004). Rolf Lie identifi ed yet another

specimen as domestic pig (A.S. Ingstad 1977:263).

This specimen was lost in the mail between Bergen

and Oslo and has therefore not been studied by

other zoologists. The existence of pigs at L’Anse

aux Meadows could be expected, as pigs formed a

substantial share of domesticates in Greenland in the

11th century (Vésteinsson et al. 2002:110).

Given the Norse dependence on dairy products,

it is almost certain that some domestic animals must

have been brought to L’Anse aux Meadows, even

if the main portion of the diet, like the fi rst years in

Iceland, came from wild animals. The absence of

barns and byres and the undisturbed vegetation are

sure signs that there could not have been many domesticates

and that, if present, they did not require

stabling for the winter. As a difference of only 2 °C

in the mean temperature can make L’Anse aux Meadows

snow-free in the winter, the latter situation was

at least a possibility (Wallace 2003a:380, 2005:28).

The fact that, with the exception of a pit feature in

room V of hall F, the large storage rooms in halls D

and F16 contained no signs of food or domestic storage

of the kind known from Iceland and Greenland is

a sign that livestock was minimal at best.

The layout. The layout of the site, with three

large halls, a small house, a hut, and three pit buildings

and with all but one pit building primarily for

accommodation, is not typical of an 11th-century

farmstead. Orri Vésteinsson’s work in Iceland has,

however, shown that several families seem to have

banded together during the very fi rst period of settle2009

B. Wallace 121

from the halls and 2 from Aboriginal features.18 Both

the Aboriginal pieces were Newfoundland jasper.

Of the other 9, all were Icelandic except for 4 in the

largest hall, which were from Greenland, supporting

the idea that the leader was Greenlandic. If this is

not Leif Eriksson’s hall, it must have belonged to

someone of his background and status.

Date of the site. The radiocarbon dates for the

Norse phase of the site ranged from ca. A.D. 650 to

1050. However, AMS radiocarbon dates on twigs

and small branches, which provide the most accurate

record, date the Norse occupation to somewhere

right before or after A.D. 1000 (Wallace 2003a:167,

2006:73).19

Relationship to other cultures on the site. Evidence

obtained so far indicates that there were probably

no Aboriginal people on the site during the

short Norse presence, but that they had been there

about a century earlier and used the site two hundred

years later.20

Hóp of the sagas

The self-sown wheat mentioned in Eiríks saga

is sometimes seen as a medieval allusion to Insula

Fortunata (Keller 2001:84, Wahlgren 1969:49). This

interpretation does not invalidate it as a historical

observation. Early French explorers made the same

discovery:

“At the head of this bay, beyond the low shore,

were several high mountains ... we caught sight of

the savages on the side of a lagoon and low beach.

...We rowed over to the spot, and fi nding there was

an entrance from the sea into the lagoon ...Their

country is more temperate than Spain ...There is

not the smallest plot of ground bare of wood, and

even on sandy soil, but is full of wild wheat, that

has an ear like barley and the grain like oats ... as

thick as if they had been sown and hoed” (Jacques

Cartier in 1534 at the head of Chaleur Bay in New

Brunswick— Cook 1993:22).

Eastern New Brunswick is known for long,

protective sandbars along its entire coast and the

warm sheltered lagoons and rivers behind them.

The butternuts and grapes grow along the Miramichi

River and Restigouche River in Chaleur Bay

(Fig. 7). This is a rich area, with large hardwood forests,

inviting meadows, grapes, and walnuts, more

like Continental Europe and very different from

Figure 7. The Gulf of St. Lawrence. Map © Google Earth.

122 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

we can take every situation depicted in the sagas at

face value. They show all the signs of the fl exibility

marking transmission of oral history, sprinkled with

later learned concepts. Did Leif Eriksson sleep at

L’Anse aux Meadows? If Leif Eriksson was a historical

person, he probably did.

Acknowledgements

Once more I would like to thank my NABO colleagues

for inspiration provided over the years by their wide variety

of research, to Gísli Sigurðsson for many stimulating discussions,

and to my husband and colleague Rob Ferguson

for reading, making suggestions, and editing my manuscript

on a topic presented to him far too many times. Thanks also

to my anonymous reviewers for useful suggestions!

Literature Cited

Anthony, D.1990. Migration in archaeology: The baby and

the bathwater. American Anthropologist 92:895–914.

Anderson, Th. M., 2000. Exoticism in early Iceland. Pp.

19–28, In M. Dallapiazza, O. Hansen, P. Meulengracht-

Sørensen, and Y.S. Bonnetain (Eds.). International

Scandinavian and Medieval Studies in Memory

of Gerd Wolfgang Weber. Parnaso, Trieste, Italy.

Barnes, G. 2001. Viking America: The First Millennium.

D.S. Brewer, Cambridge, UK.

Baumgartner, W. 1993. Freydís in Vinland oder Die Vertreibung

aus dem Paradies. Skandinavistik 23(1):16–35.

Brink, S. 2008. Slavery in the Viking Age. Pp. 59–66, In

S. Brink and N. Price (Eds.). The Viking World. Routledge,

London, UK.

Clover, C. 1986. Icelandic family sagas (Íslendingasögur).

Pp. 239–315, In C. Clover and J. Lindow (Eds.). Old

Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Critical Guide. Islandica

45. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Cook, R. 1993. The Voyages of Jacques Cartier with an

Introduction by Ramsay Cook. University of Toronto

Press, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Cook, R. (Ed. and Transl.). 2001. “Njal’s Saga.” Translated

with Introduction and Notes by Robert Cook,

2001. Penguin Books, London, UK.

Davis, A.M., J.H. McAndrews, and B. Wallace.1988.

Paleoenvironment and the archaeological record at

the L'Anse aux Meadows Site, Newfoundland. Geoarchaeology:

An International Journal 3(1):53–64.

Foley, J.M. 1991. Immanent Art: From Structure to Meaning

in Traditional Oral Epic. Indiana University Press,

Bloomington, IN, USA.

Friðriksson, A., and O. Vésteinsson. 2003. Creating a

past: A historiography of the settlement of Iceland. Pp.

139–181, In J.H.Barrett (Ed.) Contact, Continuity, and

Collapse. The Norse Colonization of the North Atlantic.

Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, Belgium.

Gleeson, P. 1979. Study of wood material from L’Anse

aux Meadows. Unpublished report for Parks Canada,

Washington Archaeological Research Center,

Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA.

Grant, D.R.1975. Surfi cial geology and sea-level changes,

L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Park, Newfoundland.

Paper 75-1, Part A, Geological Survey of

Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

northern Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland.

One could certainly see it as Hóp.

Eastern New Brunswick also harbored the densest

populations of native people in Atlantic Canada,

the ancestors of today’s Mi’kmaq. Estimates of the

total number of Mi’kmaq in protohistorical times lie

around 6000 to 15,000 (Martijn 2005:49), covering

also all of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and

other Gulf islands. Jacques Cartier’s encounter with

them parallels the Norse experience:

“... we caught sight of two fl eets of savage canoes

that were crossing from one side to the other [of

Chaleur Bay], which numbered in all some forty or

fi fty canoes. Upon one of the fl eets reaching this

point, there sprang out and landed a large number

of people, who set up a great clamour and made

frequent sign to us to come ashore, holding up to

us some skins on sticks ... they had come to barter

with us; and held up some skins of small value,

with which they clothe themselves. ... They bartered

all they had to such an extent that all went

back naked without anything on them; and they

made signs to us that they would return on the

morrow with more skins.” ( Jacques Cartier, 1534

in Chaleur Bay—Cook 1993:20–21).

Few have disputed that the description of

Skrælings travelling in húðkeipar, skin canoes, is

based on actual observation. From archaeology

and ethnology, we know that canoes were rarely

used south of central Maine, and not at all south of

Boston, where people used boats hollowed out of

trees. Thus, this observation was most likely made

north of central Maine. The Mi’kmaq did use canoes

made from moose or deer skin (Wallis and Wallis

1955:50–51, Whitehead 1991:20) and are hence not

unlikely contenders for having been the models for

the Skrælings at Hóp.

Conclusion

On the basis of the archaeological evidence at

L’Anse aux Meadows, I suggest that the structure

of the L’Anse aux Meadows site parallels the type

of site represented by Straumfjord of Eiríks saga

rauða. The organization, economy, size, buildings,

and date give greater historical validity to the Vinland

sagas than has hitherto been recognized. The

location of L’Anse aux Meadows indicates that the

Gulf of St. Lawrence through the Strait of Belle

Isle was of special interest to its occupants. The archaeological

evidence is unequivocal that visits did

take place to more southerly regions where grapes

grew wild. This is a case where archaeology can

be used to test the sagas. The Vinland sagas may

contain a greater grain of reality than we thought—

modern data have shown that the basic facts in Ari

the Wise’s Íslendingabók were correct (Friðriksson

and Vésteinsson 2003:142). It does not mean that

2009 B. Wallace 123

Martijn, C.A., 2005. Early Mi’kmaq presence in southern

Newfoundland: An ethnohistorical perspective, c.

1500–1763. Newfoundland Studies 19(1):44–102.

McAndrews, J., and A.M. Davis.1978. Pollen Analysis

at the L'Anse aux Meadows Norse Site. Ms. on fi le,

Archaeological Research Section, Canadian Parks

Service, Environment Canada, Halifax, NS, Canada

McGhee, R. 1978. Canadian Arctic Prehistory. Van Nostrand

Reinhold, Toronto, ON, Canada.

McGovern, T.H. 1981. The Vinland Adventure: A North

American Perspective. North American Archaeologist

2(4):285–308.

Mott, R.1975. Palynological Studies of Peat Monoliths

from L’Anse aux Meadows Norse Site. Geological

Survey of Canada, Paper 75-1, Part A, 1975: 451–454.

Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Nansen, F. 1911. In Northern Mists: Arctic Exploration in

Early Times. Translated by A.G. Chater. Volumes 1–2.

F.A. Stokes Co., New York, NY, USA.

Ólafsson, G., and M. Snæsdóttir.1976. Rúst í Hegranesi.

Árbók hins íslenzka fornleifefélags 1975:69–78.

Ólason, P.E. (Ed.). 1947. Heimskringla Snorra Sturlusonar.

Vol. 2. Óláfs saga helga. Menntamálaráð og

Þjóðvinafélag, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Ólason,V. 2001. Sagatekstene - forskningsstatus. Pp.

41–64, In J.R.Hagland and S.Supphellen (Eds.). Leiv

Eriksson, Helge Ingstad og Vinland. Kjelder og tradisjonar.

Innlegg ved eit seminar i regi av det Kongelige

Norske Videnskabers Selskab 13–14 oktober 2000.

Tapir, Trondheim, Norway.

Olsen, O., and O. Crumlin-Pedersen. 1969. Fem

vikingeskibe fra Roskilde fjord. Vikingeskibshallen,

Roskilde, Denmark.

Pastore, R.T. 1983. Excavations at Boyd’s Cove, Notre

Dame Bay. Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador,

Annual Report 4: 98–125.

Perkins, R. 2004. Medieval Norse visits to America: Millennial

stocktaking. Saga-Book of the Viking Society

for Northern Research 28:29–69.

Reeves, A.M. 1890, Finding of Wineland the Good. The

History of the Icelandic Discovery of America. Edited

and translated from the earliest records. To which is

added biography and correspondence of the author by

W.D. Foulke. With phototype plates of the vellum mss.

of the sagas. H. Frowde, London, UK.

Rick, A.M. 1977. Analysis of bone remains from L'Anse

aux Meadows, Newfoundland. Preliminary Report.

Ms.on fi le, Archaeological Research Section, Canadian

Parks Service, Environment Canada, Halifax,

NS, Canada.

Sejbjerg Sommer, B. 2007. The Norse Concept of Luck.

Scandinavian Studies. Available on-line at http://www.

thefreelibrary.com/The+Norse+concept+of+lucka0177634929.

Accessed 22 September 2007.

Sigurðsson, G. 2004. The Medieval Icelandic Saga and

Oral Tradition. A Discourse on Method. Publications

of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature No.

2. Translated By N. Jones. The Milman Parry Collection

of Oral Literature, Harvard University, Cambridge,

MA, USA.

Halldórsson, Ó 1980. Ætt Eiríks rauða. Gripla 4:81–91.

Halldórsson, Ó, 1986. Lost tales of Guðríðr Þorbjarnardóttir.

Pp. 239–242, In R.Simek, J. Kristjánsson, and H.

Bekker-Nielsen (Eds.), Sagnaskemmtun. Studies in

Honour of Hermann Pálsson on his 65th Birthday 26 May

1986. Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, Weimar, Germany.

Henningsmoen, K.E. 1977. Pollen-analytical investigations

in the L'Anse aux Meadows area, Newfoundland.

Pp. 289–340, In A.S. Ingstad, The Discovery of a

Norse Settlement in America. Universitetsforlaget,

Oslo, Norway.

Hermannsson, H. 1954. Tyrkir, Leif Erikson’s fosterfather.

Modern Language Notes 69(6):388-393.

Hosie, R.C. 1979. Native Trees of Canada. Fitzhenry and

Whiteside Ltd. in co-operation with the Canadian Forestry

Service (Environment Canada) and the Canadian

Government Publishing Centre. Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Ingstad, A.S. 1977. The Discovery of a Norse Settlement

in America: Excavations at L'Anse aux Meadows,

Newfoundland, 1961–1968. Universitetsforlaget,

Oslo, Norway.

Ingstad, A.S., and H. Ingstad. 1986. The Norse Discovery

of America. Vols. I and II. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo,

Norway.

Ingstad, H.1960. Landet under leidarstjernen. En ferd til

Grønlands norrøne bygder. Gyldendal norsk forlag,

Olso, Norway.

Ingstad, H. 1966. Westward to Vinland: The Discovery of

Pre-Columbian Norse House-Sites in North America.

Jonathan Cape, London, UK.

Jansson, S.B.F. 1945. Sagorna om Vinland. Handskrifterna

till Erik den Rödes saga. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie

och Antikvitets Akademiens handlingar del 60:1.

Wahlström och Widstrand, Stockholm, Sweden.

Keller, C. 1991. Vikings in the West Atlantic: A Model of

Norse Greenlandic Medieval Society. Acta Archaeologica

vol. 61 (1990):126–141. Munksgaard, Copenhagen,

Denmark.

Keller, C. 2001. Vínland etter Ingstad. Pp. 67–85, In J.R.

Hagland and S. Supphellen (Eds.). Leiv Eriksson,

Helge Ingstad og Vinland. Kjelder og tradisjonar.

Innlegg ved eit seminar i regi av det Kongelige Norske

Videnskabers Selskab 13–14 oktober 2000. Tapir,

Trondheim, Norway.

Kristjánsson, J. 2005. The First Settler of the New World.

The Vinland Expedition of Thorfi nn Karlsefni. University

of Iceland Press, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Kristensen, T. 2008. AM-2008-1827 Progress report:

L’Anse aux Meadows Aboriginal Archaeology Project.

In-house report, Memorial University of Newfoundland,

St. John’s, NL and Parks Canada Agency,

Atlantic Service Centre, Halifax, NS, Canada.

Lynnerup. N. 1998. The Greenland Norse: A Biological-

Anthropological Study. Meddelelser om Grønland,

Man and Society 24. Copenhagen, Denmark.

Lynnerup, N. 2003. Paleodemography of the Greenland

Norse. Pp. 133–144, In S. Lewis-Simpson (Ed.). Vinland

Revisited: The Norse World at the Turn of the

First Millennium. Selected Papers from the Viking

Millennium International Symposium, 15–24 September

2000, Newfoundland and Labrador. Historic

Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador, St.

John’s, NL, Canada.

124 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 2

Smith, K.P. 2000. Jasper cores from L’Anse aux Meadows.

P. 217, In W.W. Fitzhugh and E.I. Ward (Eds.).

Vikings. The North Atlantic Saga. Smithsonian Institution,

Washington DC, USA.

Smiley, J. (Ed.). 2000. The Sagas of Icelanders: A Selection.

Introduction by Robert Kellog. Penguin, London,

UK.

Snow, D.R.1978. Late prehistory of the east coast. Pp. 58–

69, In W.C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.) and B.Trigger (Vol.

Ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Volume

15 (Northeast). Smithsonian Institution, Washington

DC, USA.

Spiess, Arthur. 1987–88. Faunal remains – They may hold

enough information to be called archaeological guidebooks.

The Northern Raven VII (2):14-23.

Spiess, A. 1990. Preliminary identifi cations of calcined

bone from L’Anse aux Meadows. Typescript report

for Parks Canada, Atlantic Service Centre, Halifax,

NS, Canada.

Stefánsson, M. 1993. Iceland. Pp. 311–320, In P. Pulsiano,

K. Wolf, P. Acker, and D. Fry (Eds.). Medieval Scandinavia,

an Encyclopedia. Garland Publishing, New

York, NY, USA.

Stewart, F. 2004. Letter dated November 15, 2004.

Trigger, B.G. 1982. Response of native peoples to European

contact. Pp. 139–155, In G.M. Story (Ed.). Early

European settlement and Exploitation in Atlantic

Canada. Memorial University of Newfoundland, St.

John’s, NL, Canada.

Sveinsson, E.Ó (Ed.). 1954. Brennu-Njáls saga. Íslenzk

fornrit 12. Hið íslenzka fornritafélag, Reykjavik,

Iceland.

Vésteinsson, O. 1998. Patterns of Settlement in Iceland: A

Study in Prehistory. Saga-Book of the Viking Society

for Northern Research 25:1–29.

Vésteinsson, O. 2004. Icelandic farmhouse excavations:

Field methods and site choices. Archaeologia Islandica

3:71–100.

Vésteinsson, O., T.H. McGovern, and C. Keller. 2002.

Enduring impacts: Social and environmental aspects

of Viking Age settlement in Iceland and Greenland.

Archaeologia Islandica 2:98–136.

Wallis, W.D., and R.S. Wallis. 1955. The Micmac Indians

of Eastern Canada. University of Minnesota Press,

Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Wahlgren E. 1969. Some Further Remarks on Vinland.

Scandinavian Studies 40(1):26–35.

Wallace, B.L. 1991. L'Anse aux Meadows, Gateway to

Vinland. Acta Archaeologica 61:166–198.

Wallace, B. 1999. An archaeologist discovers Acadia. Pp.

9–27, In M. Conrad (Ed.). Looking into Acadie: Three

Illustrated Studies. Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax,

NS, Canada.

Wallace, B. 2003a. Later excavations at L’Anse aux

Meadows. Pp. 165–180, In S. Lewis- Simpson (Ed.).

Vínland Revisited. The Norse World at the Turn of

the First Millennium. Selected Papers from the Viking

Millennium International Symposium 15–24 September

2000, Newfoundland and Labrador. Historic Sites

Association of Newfoundland and Labrador, Inc. St.

John’s, NL, Canada.

Wallace, B. 2003b. Vínland and the death of Þorvaldr.

Pp. 337–390, In S. Lewis- Simpson (Ed.). The Norse

World at the Turn of the First Millennium. Selected

Papers from the Viking Millennium International

Symposium 15–24 September 2000, Newfoundland

and Labrador. Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland

and Labrador, Inc. St. John’s, NL, Canada.

Wallace, B. 2003c. L’Anse aux Meadows and Vinland:

An abandoned experiment. Pp. 207–238, In J. Barrett

(Ed.). Contact, Continuity, and Collapse: The Norse

Colonisation of the North Atlantic. Studies in the Early

Middle Ages. Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, Belgium.

Wallace, B. 2005. The Norse in Newfoundland: L’Anse

aux Meadows and Vinland. Newfoundland Studies

19(1):5–43.

Wallace, B. 2006. Westward Vikings: The L’Anse aux

Meadows Saga. Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland

and Labrador, Inc., St. John’s, NL, Canada.

Whitehead, R.H. 1991. The Old Man Told Us: Excerpts

from Micmac History, 1500–1950. Nimbus, Halifax,

NS, Canada.

Þórláksson, Helgi. 2001. The Vinland Sagas in Contemporary

Light. Pp.63-77, In A.Wawn and Þ. Sigurðardóttir

(Eds.) Approaches to Vinland. Proceedings

of a conference on the written and archaeological

sources for the Norse settlements in the North-Atlantic

region and exploration of America. held at The Nordic

House, Reykjavik 9-11 August 1999. Sigurdur Nordal

Institute, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Endnotes

1Ólafur Halldórsson (1980) suggests that Leif was originally

named Þorleifr after his great-grandfather. According

to Ólafur, this earlier Þorleifr, with his father Þorvaldr,

left Norway for Iceland and settled at Drangar, later

moving to Breiðafjörður. Erik the Red must therefore

have been born in Iceland. Ólafur bases his conclusion on

Ari fróði’s Íslendingabók.

2Leif’s byname is usually associated with one of these

events; Ólafur Halldórsson (1986:245) has suggested

that it stemmed from the fact that Gudrid was among the

shipwrecked people rescued by Leif.

3Grænlendinga saga states that “After this he was called

Leif the Lucky,” but it is not clear if this refers to fi nding

Vinland or rescuing a ship-wrecked crew from a reef.

In Eiríks saga, the appellative follows Leif’s supposed

Christianization of Greenland.

4The Vinland sagas is here meant to comprise what is commonly

referred to as The Greenlanders’ Saga (Grænlendinga

saga in Flateyjarbók, GKS 1005 fol.) and Erik the

Red’s Saga (Skálholtsbók, AM 557 4to, and Hauksbók,

AM 544 4to). The English translations cited are those by

Keneva Kunz in the 2001 Penguin edition of The Sagas

of Icelanders.

5Thorarinn says, “Valuable are the Ruler’s words, but

what do you want to ask from me?” He [the King] says,

“That you take Hrærik to Greenland and deliver him to

Leif Eriksson.” Thorarinn responds, “I have never been

to Greenland.” The King says, “A seafarer like you, you

now have your opportunity to go to Greenland if you have

never been there before” (author’s translation).

2009 B. Wallace 125

6“Thorvald felt they had not explored enough of the land.”

(Grænlendinga saga, The Sagas of Icelanders, Smiley

2000:642); “... the trip seemed to bring men both wealth

and renown...journey to Vinland...and have a half-share

of any profi ts from it” (Grænlendinga saga, The Sagas

of Icelanders, Smiley 2000:648; “They took few trading

goods, but all the more weapons and provisions” (Eiríks

saga rauða, The Sagas of Icelanders, Smiley 2000:662);

“They had brought all sorts of livestock and explored

the land and its resources ... They paid little attention to

things other than exploring the land” (Eiríks saga rauða,

Smiley 2000:667). Bringing livestock does not in itself

indicate colonization. Livestock would have been an

essential share of the provisions needed to feed sixty or

more people for two to three years.

7Many have pointed to the words uttered by Thorvald in

Grænlendinga saga: “This is an attractive spot, and here

I would like to build my farm” (Grænlendinga saga, Smiley

2000:642)—the original word being bær, ... bæ minn

reisa (Flateyjarbók col. 283b, Grænlendinga saga 10,

Reeves 1890:149) having the connotation of permanent

farm buildings. However, this does not suggest abandonment

of a Greenland property, only an addition. By the

same token the statement in Grænlendinga saga (Smiley

2000:646) that “They took all sorts of livestock with them,

for they intended to settle in the country if they could (byggja

landit, ef þeir mætti þat; Reeves 1890:153, emphasis

added) does not necessarily mean anything more than they

intended to add to their holdings in Iceland.

8“He selected his companions for their strength and size”

(Grænlendinga saga, Smiley 2000:643).

9Stefan Brink (2008:53) says that fóstri was a slave

brought up in the household. It could also be a slave

who brought up the household children. (Cf. Sveinsson

1954:29–31 and Robert Cook’s note 2001:313).

10The name Leifsbúðir continued in use. The logical sequence

would be demolition of the búðir and reuse of the

sod in the walls of the halls.

11Skálholtsbók has the word bygðir (Jansson 1945:70,

341).

12The suggestion that the limit for butternut trees stretched

farther north during the warmer temperatures of the 11th

century (Perkins 2004:59) is probably unrealistic. The

trees grow among stands of mixed, primarily deciduous

forests, in the southeastern portion of the Great Lakes-

St. Lawrence Forest Region and the western section of

the Acadian Forest Region (Hosie 1979:134). A greater

fl uctuation than 2° C would be required for a signifi cant

change in these regions.

13If one follows the Labrador coast from the north, Belle

Isle comes into vision as one enters the mouth of the

Strait. Then, as the Strait narrows, land appears on the

port side. If one crosses the Strait there, one ends up in

the vicinity of L’Anse aux Meadows.

14The bay is shallow, today on the average of 1–2 m. It

would have been deeper a millennium ago due to a

subsequent land rise of about 1 to 1.5 m (Grant 1975).

Consequently Black Duck Brook would have been somewhat

deeper and wider, the entire brook basin possibly

occasionally fl ooding.

15An analysis of microfauna has not yet been undertaken,

but stratigraphic soil samples are available and an analysis

is forthcoming.

16Room I in hall D, rooms V and VII in hall F. They were

interpreted as storage rooms because, although enclosed

by walls, they contained no features or organic deposits.

17The estimate is based on the time spent by 12 local fishermen

cutting the sod, felling and shaping the timber,

the amount of materials used, and the time spent on the

construction. While the manual skill and strength of

these men probably came close to that of the Norse, they

lacked previous experience of this type of construction,

but this was offset by the modern tools used, e.g., trucks

for transportation.

18Another piece was found a few meters west of hall F

in 2008 (Kristensen 2008), but it has not yet been analyzed.

19The stratigraphy shows clearly that the Norse phase was

one single, short-lived occupation (Wallace 2003c:230).

20Before the Norse, the site was intermittently occupied by

the Maritime Archaic, Groswater Dorset Palaeoeskimo,

and “Recent Indians”; subsequently by Little Passage

(Wallace 2006:85–90).