[an error occurred while processing this directive]

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

42

Introduction

How did the state-formation processes affect the

administrative system and assembly organization in

southeast Norway in the period between

the 11th and 14th centuries? On a regional

level, it has been assumed that the king

took control over the assembly organization

through his representatives in this

period, by strategically moving them

closer to royal farms or other centers

(Andersen 1977:248–255, 1982a:358).

These assumptions have, however, never

been thoroughly investigated for the

geographically confined area of southeast

Norway. To examine this question,

I have studied parts of this area, namely

the medieval landscape of Viken in

the Oslo Fjord region, which includes

the county of Bohuslän in present-day

Sweden. According to the Saga of Olaf

the Holy, the area consisted of three

medieval counties, or Old Norse fylki,

which were unified during King Olaf II

Haraldsson’s reign at the beginning of

the 11th century (Sturluson 1979:246–

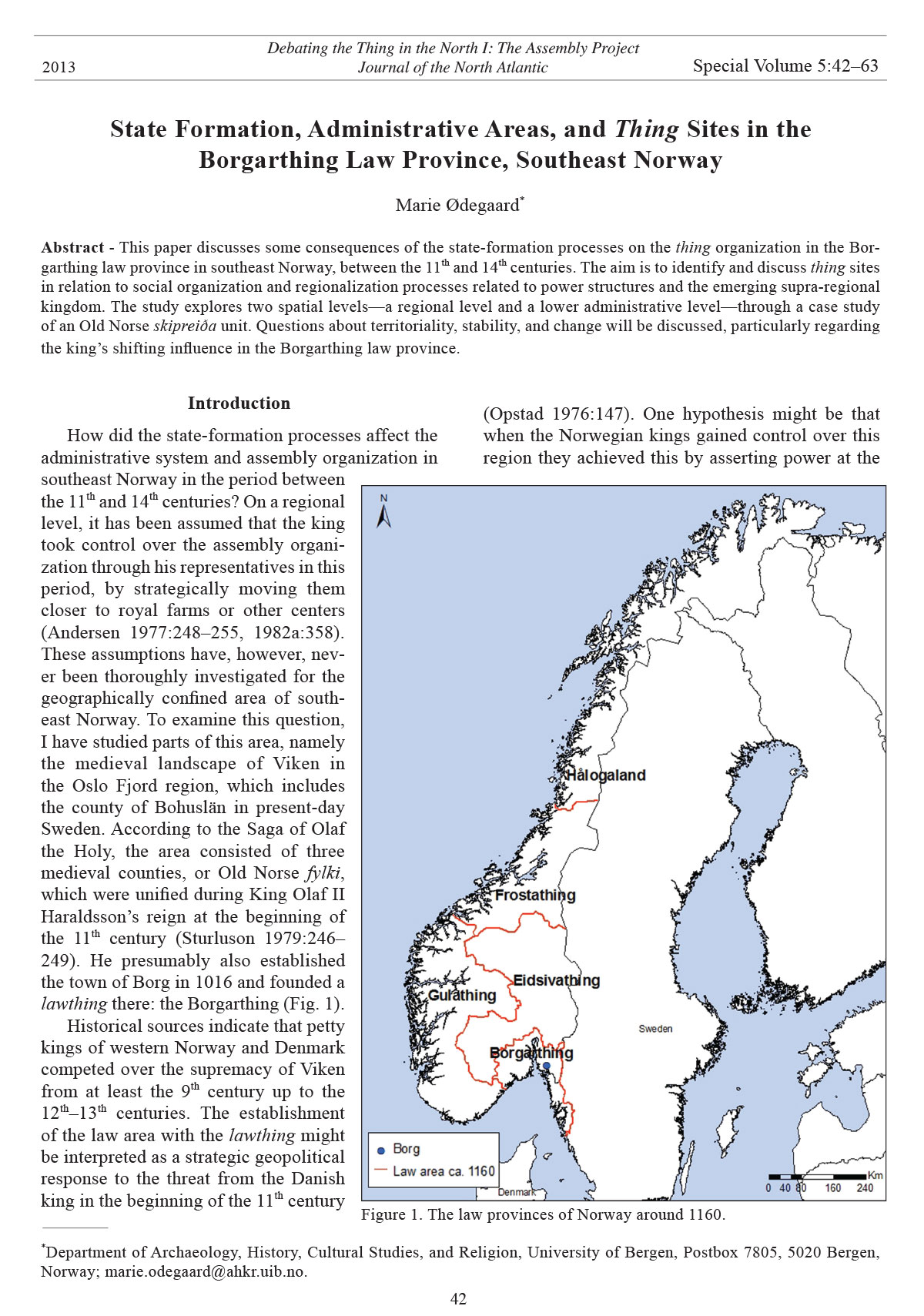

249). He presumably also established

the town of Borg in 1016 and founded a

lawthing there: the Borgarthing (Fig. 1).

Historical sources indicate that petty

kings of western Norway and Denmark

competed over the supremacy of Viken

from at least the 9th century up to the

12th–13th centuries. The establishment

of the law area with the lawthing might

be interpreted as a strategic geopolitical

response to the threat from the Danish

king in the beginning of the 11th century

(Opstad 1976:147). One hypothesis might be that

when the Norwegian kings gained control over this

region they achieved this by asserting power at the

State Formation, Administrative Areas, and Thing Sites in the

Borgarthing Law Province, Southeast Norway

Marie Ødegaard*

Abstract - This paper discusses some consequences of the state-formation processes on the thing organization in the Borgarthing

law province in southeast Norway, between the 11th and 14th centuries. The aim is to identify and discuss thing sites

in relation to social organization and regionalization processes related to power structures and the emerging supra-regional

kingdom. The study explores two spatial levels—a regional level and a lower administrative level—through a case study

of an Old Norse skipreiða unit. Questions about territoriality, stability, and change will be discussed, particularly regarding

the king’s shifting influence in the Borgarthing law province.

Debating the Thing in the North I: The Assembly Project

Journal of the North Atlantic

*Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies, and Religion, University of Bergen, Postbox 7805, 5020 Bergen,

Norway; marie.odegaard@ahkr.uib.no.

2013 Special Volume 5:42–63

Figure 1. The law provinces of Norway around 1160.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

43

lower administrative levels. Viken had an administrative

system connected to the royal maritime defence

at an early stage of the kingdom in the 10th–11th

centuries: the ON skipreiða (Bjørkvik 1982:546–

551); however, the skipreiður also functioned as

judicial areas for the rural assemblies. Altogether, 48

skipreiður are known in the Borgarthing law provinc

in 1277 (DN IV:3; Lange and Unger 1857:3). According

to a hypothetical and arithmetical principle,

it has been assumed that every skipreiða had four

thing sites, corresponding to one in each quarter

(fjórðungr). One of these sites may have been shared

by the entire skipreiða for discussion of mutual

matters, such as weapon inspections and taxes (Andersen

1982a:346–359). Nevertheless, both these

types of assemblies are assumed to be althings,

where all free men would meet (e.g., Indrebø 1935,

Norseng 2005:257). It is, however, still somewhat

unclear if the administrative areas in Viken were

older jurisdictional districts which the king later

built his organization on, or whether he created new

administrative units for Viken when gaining control

over the area (e.g., Bull 1918:257–273, Indrebø

1935:153–168, Tunberg 1918).

Is it possible to trace such a development through

the sources and in the landscape? This study will focus

on two different spatial levels: a regional macro

and a local micro level. At the local level, a case

study of one of the skipreiður—Eiker, in the present

Buskerud county—will be presented including

the different administrative areas, and the possible

changes regarding questions of territorialization,

stability, and change will be considered.

Methods and Sources

Archaeological monuments, such a burial

mounds and standing stones, are important features

for assemblies in northern Europe (e.g., Brink 2004,

FitzPatrick 2004, Larsson 1998, Sanmark and Semple

2010) and may potentially identify thing sites.

However, since few thing sites are known from Norway,

the characterization of their archaeological and

topographical attributes remain uncertain. Therefore,

as a point of departure, later medieval legal

documents, together with place-names, may be used

to identify thing sites. If medieval assemblies can be

identified and located, they might provide clues as to

where the assemblies were held at an earlier stage in

history. I have studied diplomas from the 14th to the

17th centuries for the whole Borgarthing law province,

combined with research on place-names and

secondary literature related to the theme (e.g., Bugge

1918, Bull 1924, Indrebø 1935). Altogether, approximately

1800 diplomas that might relate to thing

sites have been registered, and a total of 195 possible

assembly sites have been documented. Compared

to previous research, several new thing sites have

in this way been identified in the Borgarthing law

province. A classification of the sources and their

value for identifying the thing sites are therefore

necessary. I have divided the sites into two categories:

certain and possible thing sites. Several diplomas

use the term “the correct thing site” (e.g., “a

rettom stemfnabø”), indicating legally recognized

sites (cf. Sandnes 1982:380). These sites may also

be indicative of older traditions, and they constitute

the majority in the category of certain thing sites.

No precise rules separating the cases conducted at

the thing sites from those by local ad hoc commissions

(skiladómr/sættarstefna) are found, except

that manslaughter and claims to oðal, i.e., an option

for relatives to buy or redeem land (Robberstad

1981:493–499), should be announced at the thing

(Imsen 1990:197, Myking 2007:191–194). Furthermore,

some diplomas use the ON term stefna (i.e.,

assembly), but these usages do not necessary refer to

the legally recognized sites. Therefore, I have found

it necessary to include a category of possible thing

sites, and this also includes sites signalled by placenames.

The documents rarely specify exactly where

on the farms assemblies were held. Thus, in most

cases, I have used the denoted farm as an analytical

category at the local level.

According to the afore-mentioned arithmetic

principle, each skipreiða should, in theory, have

four fjórðungar, each with their own assembly site

(Indrebø 1935:136–168), which adds up to 192 expected

medieval thing sites in Viken. So far these are

all unknown. Some sites might also have been common

for larger areas with other functions, or may

have been moved, etc. If more than four things sites

are located in one skipreiða, as has been proposed

in earlier research (Bugge 1918, Bull 1924, Indrebø

1935), then there might be changes or assemblies on

different geographical and hierarchical levels. Of the

recorded 195 potential medieval thing sites, 78 are

classified as certain thing sites and 117 as possible,

according to my criteria (Fig. 2).

Since assemblies are closely connected to their

judicial areas, I have mapped the different medieval

administrative areas of the Borgarthing law area,

based on historical information (Bull 1930, Indrebø

1935) and cadastres of 1647 (Fladby and Imsen

1971), rectified after historic maps1 (Gjessing 1857)

in a geographical information system (GIS) (ArcMap

9.3). Historical documents can give information

concerning which administrative district the different

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

44

farms belonged to, and thus the modern-day farm

boundaries are used together with topographical

features, to identify the outer borders of the medieval

administrative units. Even though the farm boundaries

may have changed since the Middle Ages, from

a larger perspective the reconstructed administrative

areas will still give visual impressions of the areas in

question. The boundaries of parishes and fjórðungar

sometimes coincide in Viken (see Indrebø 1935, Lunden

1965:274–275); thus in some cases, the oldest administrative

boundaries and possible changes during

the Middle Ages can be traced through a combination

of secular and ecclesiastical boundaries, together

with topographical landscape features.

The northern European practice of re-use of prehistoric

monuments on thing sites, especially burial

mounds, is well documented (e.g., Brink 2004, Fitz-

Patrick 2004, Larsson 1998, Sanmark and Semple

2010). Therefore, relevant archaeological sites and

monuments, such as burial mounds and medieval

churches, together with place-names, have been recorded

in the GIS. As for place-names, discrepancy in

expected structures may be interpreted as expressions

of change, both regarding the assemblies’ location

and the names of the administrative areas.

Prehistoric burial mounds have been interpreted

as markers of proprietary rights to land and as symbols

of free landowners (Iversen 1999, 2008; Skre

1998; Zachrisson 1994). The Law of the Gulathing

states that only free men of full age can attend the assembly,

and that the handling of weapons should be

controlled (G 309; Eithun et al. 1994:166–167). It is

likely that the right to carry weapons was regulated

also in earlier times (Hofset 1981, Martens 2003).

Furthermore, it is assumed that residences of powerful

families were closely connected to the thing sites

for purposes of controlling the meetings (Andersen

1977:255, Imsen 1990:198). In this regard, weapon

graves could be interpreted as markers of free,

weapon-bearing men, who played a prominent role

at the thing meetings. To study which types of farms

housed assemblies is therefore important for identifying

who may have controlled the meetings and if

powerful families were at all influential regarding

Figure 2. Certain and possible thing sites recorded in the research area.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

45

the location of the assembly sites. The size of the

farm, and if they were “normal”, magnate, or royal

farms, could thus be important. Did size matter, or

was perhaps geographical location more significant?

The cadasters from the 17th century are important

for shedding light on this question (e.g., Farbregd

1984, Holmsen 1940), and the case study of Eiker

will scrutinize this material in detail. In this way,

different places and patterns in the landscape will

be studied in relation to each other, both at micro

and macro levels. Therefore, I examined different

geographical levels and structures collectively and

comparatively to provide a more comprehensive

understanding of the administrative landscape and

to assess the relevance of a variety of concepts such

as centrality, stability and change, and temporality.

Thing Sites and Administrative Areas in the

Borgarthing Law Area

The origin, age, and relationship between the

different administrative levels within the Borgarthing

law province is a disputed topic. Information

about the oldest organizational structure of the law

province derives from sagas and early laws. Four

geographical levels are identified in the medieval

period (Fig. 3). For Viken, the oldest surviving

Christian laws, of which some of regulations may

date back to the 11th century (Halvorsen 2008),

presuppose six fylkir-churches, i.e., main churches,

in three fylkir (Fig. 4). In practice, this indicates a

half-fylki division (Taranger 1887, 1935:27), which

corresponds to the historically known sýslar-divisions.

The churches are Konghelle and Svarteborg

in the medieval Ranrike fylki in Bohuslän, Tune

and Aker in Vingulmork fylki, as well as Sem and

Hedrum in Vestfold fylki (Halvorsen 2008:133;

Indrebø 1931; Munch 1846:343–344, 358, 367).

These churches are considered to be among the oldest

churches in the country, probably erected in the

first half of the 11th century, but this is not archaeologically

verified. It is assumed that the king played

a central role in the processes of early Christianization

and was instrumental in erecting these churches

(Skre 2007:393), as they are often located on

royal estates (Sandnes 1969, Skre 1998:93–104).

This connection to the king seems to apply to all six

fylkir-churches in Viken. These churches often had

special rights to income, and were built to serve a

larger region. They housed standard weights, an

indication of judicial functions, and should, according

to the law, be maintained by the farmers in the

region (B8; Halvorsen 2008:133). It is therefore

likely that the establishment of Christianity was approved

by participants at the assemblies (Andersen

1977:191).

As no fylkir-churches are known in Grenland

(Fig. 4), the area’s connection to the Borgarthing

law area is debated (e.g., Bull 1930, Indrebø 1931,

Storm 1877). It seems that Grenland’s connection to

the law province may have changed over time (M.

Ødegaard, unpubl. data.). In 1223, the law province

most likely consisted of two smaller legislative

areas, so-called lagsogn, indirectly evidenced in

the Saga of Hákon Hákonson (Þorðarson 1979:91)

listing nine lawspeakers (lǫ gmaðr) in Norway, of

which two came from the Borgarthing-area. This

division may, however, represent an older situation.

During the 13th century, several changes were made

regarding the legal territories, and the lawthing at

Borg may well have gone out of use as a common

lawthing shortly afterwards (Seip 1934:8–16).

The afore-mentioned sýslur were larger administrative

areas managed by the king’s “faithful” men,

given as fiefs, perhaps as early as the 10th and 11th

centuries in this area (Norseng 2005:61–62). From

the 13th century, the Borgarthing area was divided

into six sýslur, probably increasing to eight later

on (Fig. 5; Helle 2001:152).2 The sýslur were units

for economic, military, and judicial purposes. Their

names indicate the administrative centers and seats

for the royal officials of the sýslur (sýslumaðr)

upon these areas’ emergence (Andersen 1982b:648,

Norseng 2005:64). It is unknown if the sýsla boundaries

were based on older divisions (Jørgensen

1974:242). As there is no knowledge of thing sites

at the fylki-level, one cannot rule out that the fylkir

Figure 3. The different geographical and hierarchical lev- originally had common thing sites, like the so-called

els in the Borgarthing law province in the Middle Ages.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

46

landsting known from Denmark and Sweden (Jørgensen

1974:238–240, Rosén 1981:293–296), and

that the sýslar-thing or the main lawthing replaced

them. Furthermore, it is unknown if the sýslur had

any impact on the assembly organization at lower

levels, but it is likely that the sýslumaðr attended

Figure 4. The four fylkir in Viken in the Middle Ages with the fylkir-churches.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

47

Hertzberg 1914; Steinnes 1929). As the Law of the

Gulathing stated how many ships each law area were

supposed to provide for the naval fleet (leiðangr; G

315; Eithun et al. 1994:170), the organization of naval

defence could be old. When the term skipreiður

appears in the sources at the beginning of the 13th

the skipreiður assemblies (L I:8, III:12; Taranger

1915:13–14, 37–38).

Since the coastal and core regions of the law area

were primarily divided into skipreiður, the other

divisions and their extent are a much-debated topic

(e.g. Bull 1918, 1930; Ersland 2000; Hasund 1921;

Figure 5. The sýslur in Viken with the fylkir-churches.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

48

royal regulation at lower levels be traced? To discuss

this, I will now turn to the case study of Eiker, in

Buskerud county.

Eiker: A Local Case Study

Five thing sites have been recorded in Eiker

between the 14th and 17th centuries (Fig. 7). Three

are categorized as certain thing sites, located on the

farms of Berg, Sanden, and Hedenstad,3 while two

assemblies have only been categorized as possible:

Fiskum and Haug.4 In order to assess the assembly

sites in chronological terms together with possible

processes of stability or change, I will examine how

the different assemblies were located in relation to

their judicial areas.

Questions remain over whether Eiker was originally

part of the skipreiður organization or whether

it was based on another system (Bull 1920:136,

Steinnes 1933:57). That Eiker was divided into

fjórðungar could indicate that the area was originally

a skipreiða (cf. Indrebø 1935). In addition, the farmers

of Eiker bought a ship in the 1390s (DN II:519,

century, it seems to refer to fixed districts for the

payment of royal taxes.

It has been assumed that the skipreiður divisions

were mapped onto an older division of herað

units, further subdivided into quarters. This division

may have been introduced by Danish kings prior

to the 11th century (Fig. 6) (e.g., Bull 1918, Sogner

1981:492–494, Tunberg 1911). The origin of the herað

is unknown, but since the borders often coincide

with topographical borders, they may be based on

older divisions between rural districts (cf. Jørgensen

1974:235–236). The different sizes of the skipreiður/

herað and the unequal distribution of the fjórðungar

may indicate chronological differences or different

political affiliations (Fig. 6; Bull 1920:142–143;

Steinnes 1929; M. Ødegaard, unpubl. data).

The different administrative areas with assemblies

of different functions and levels indicate a rather

regulated system. Most of these administrative

divisions appear in the sources as districts with set

boundaries at the same time as society became more

tightly organized by a central power. So how were

the rural assemblies organized? Can any attempts of

Figure 6. The known skipreiður and fjórðungar boundaries in the Norwegian part of the Borgarthing law province ca. 1300.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

49

II:562; Lange and Unger 1851:398–399, 1852:427–

248), evidently a ship for the naval fleet, the leiðangr

(Indrebø 1935:110, Moseng 1994:76–80). In 1665,

however, Eiker had a total of six fjórðungar (Indrebø

Figure 7. The investigation area, Eiker skipreiða, with the recorded thing sites and fjórðungar boundaries.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

50

Figure 8. Eiker skipreiða with the parish boundaries. A parish boundary for Berg is suggested, but it is uncertain which farms

belonged to this parish in the early Middle Ages, as the parish became a part of Haug parish around 1400.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

51

that the parish and fjórðungar boundaries did not

coincide in Eiker. Written and archaeological sources

seldom give information of the exact location and

functions of the assemblies. However, some information

is found in a few of the diplomas from the

farms with churches. At Fiskum, Berg, and Haug,

the diplomas state that the assemblies were held either

in the church, churchyard, or the “living room”

(setstofa) of the farms.6 Assemblies in churchyards

are also known from the sagas (e.g., Þorðarson

1979:183–184) and other parts of the law area. More

uncommon is that two diplomas from Berg also indicate

the function of the thing, and refer to it as an

“ordinary weapon thing” (DN VI:451, 1434; NHD 2

r. III (2):25, 1611; Thomle 1987:25; Unger and Huitfeldt-

Kaas 1864:475–476), denoting an assembly

where the weapons of the naval fleet were inspected

by royal officials (Fig. 9). This reference suggests

that Berg had an assembly of a higher level and was

the main thing site of the skipreiða (L III:12; Taranger

1915:37–38). The term weapon thing also testifies

to the close relationship between the military

and legal aspects of the thing organization. About

100–200 m east of the farm and the medieval church

at Berg is a small hill called Pilhaugen (“The arrow

mound”).7 From Sweden and England, it is well attested

that assemblies were held both at natural and

man-made mounds, often burial mounds (Pantos

1935:105), obviously a secondary phenomenon, suggesting

changes in the administrative areas. According

to the Norwegian historian and philologist Gustav

Indrebø, two of the fjórðungar were divided in two

during the 16th century, indicating that the original

four medieval, or pre-14th century, fjórðungar in Eiker

are Varlo, Fiskum, Hedenstad, and Sanden (Fig. 7)

(Indrebø 1935:107–110). Consequently, when analyzing

the medieval thing organization, these fjórðungar

must be used.

Three of the four fjórðungar are named after a

farm with a thing site; the certain thing sites at Sanden

and Hedenstad, and the possible assembly at Fiskum.

In the last fjórðungr, Varlo, there were, however, two

possible thing sites—at Berg and Haug—but only

at Berg is the site considered a certain thing site. It

has been assumed that the oldest fjórðungr is named

after the farm which was the legal center within the

fjórðungr when it was established (Moseng 1994:94,

cf. Norseng 2005:64), thus indicating that the farm

Varlo may have had a thing site. The written sources

do not, however, indicate that Varlo had any assembly

functions,5 although these may, of course, have been

moved at an earlier point in time.

There were three churches in Eiker in the Middle

Ages: Fiskum, Haug, and Berg, all on farms with

possible assembly sites (Fig. 8). Both Haug and Berg

were located in the same fjórðungr, demonstrating

Figure 9. The farm Berg today. “The arrow mound”, now demolished, was located just left of the photo’s edge.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

52

and Semple 2004, Sanmark 2009, Turner 2000). The

name Pilhaugen is also interesting, as assemblies

could be called by “arrow” (ǫ r) or “thing summons”

(þíngsboð). Arrow summons is mentioned

in the Law of the Gulathing (G 131; Eithun et al.

1994:102–103) for cases such as murder (Andersen

1982a:348, Grieg 1980:338–340). When the leiðangr

was transformed into an annual tax for the years

when the ships were not in use, probably between ca.

1150–1300, the weapon assembly became important

for tax collections (Bjørkvik 1981:433–442; Bull

1920:38, 43–45; Ersland 2000:55). Thus, the assembly

became an administrative level for economic

transactions and taxes to the king (Moseng 1994:90).

It is therefore interesting to observe that Berg’s

neighboring farm, Sem (Fig. 10), was a royal

residence from at least 1240 until 1541 (Johnsen

1914:102). It is, however, unclear whether the farm

held this status also in previous times. Sem was a

so-called “free-farm”, which was a special royal,

administrative farm (Bjørkvik 1968:66). Only eight

such royal farms existed at that time in Norway. In

1388, Sem became the aristocratic manor and center

in the newly established Eiker fief (DN I:511; Lange

and Unger 1847:374–375). Thus, the administration

of Eiker seems to be centered on Berg and Sem,

at least from the 13th century onwards (Moseng

1994:113). The travelling distance to the thing sites

may have been decisive for their location, even

though one should be careful in assuming that principles

of short geographical distances were important

in the Middle Ages and earlier.8 All assemblies

in Eiker are centrally located within their respective

fjorðungr (Fig. 7), except for Berg, which is located

in the middle of the skipreiða, which again fits well

with the interpretation of the site as the main assembly

site of this unit.

What characterizes the farms with assembly

sites in Eiker? Hedenstad was originally royal land

(Bjørkvik 1968:59–60). At the beginning of the 16th

century, the nobleman Per Hanssøn Basse bought

several farms from St. Hallvard’s Church (DN

IV:1119, VII 741; Lange and Unger 1858:822–823;

Unger and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1869:792–793), including

Fiskum and parts of Sanden. Such farms may originally

have belonged to the king (Moseng 1994:204–

211), but will be considered here as belonging to the

church, together with Haug farm. The main part of

Sanden belonged to farmers in 1647, and Varlo was

partly owned by farmers and noblemen (Table 1). In

the Middle Ages, the farms were divided into three

fiscal units: large, medium, and small. Sanden and

Varlo were fiscally considered to be large farms,

which might indicate that the farmers belonged to an

upper stratum of society. Fiskum, on the other hand,

was considered as a medium farm, while the ownership

and land rent of Berg is unknown.9 However, in

1347, a man called Solve at Berg, Sauli a Berghi, is

mentioned as one of the king’s “faithful men” (DN

III:248; Lange and Unger 1853:209–210), indicating

that Berg was connected to the highest Norwegian

aristocracy, linked to the royal administration at the

time. Several noble families also lived at Berg from

the late 14th century onwards (Austad 1974:63, Moseng

1994:48).

All farms with assemblies included here had prehistoric

graves, although none of these had late Iron

Age weapons (Fig. 11), despite the fact that Eiker

had a large number of such burials. In Eiker, as many

as 50% of the graves contained weapons, while in

the province of Vestfold, only 10% had weapons

(Mikkelsen 2006:48). However, it must be emphasized

that not all pre-historic graves have been excavated,

and these assertions are only based on the

known material. Interestingly, at Hoen, the neighboring

farm to Varlo, the Hoen hoard was found.

This is the most important hoard in the country, and

possibly also in Scandinavia, from the Viking period

(Wilson 2006:13). Thus, Hoen and the area around

Varlo appear to have been equally important from

the end of the Viking Age, both in terms of wealth

and communication routes, since it was possible to

sail from the Oslo Fjord to Hoen in the medieval

period (Fig. 11; Mikkelsen 2006). Communication

is often considered to be a highly important feature

of thing sites (Sanmark 2009).

Several place-names in Eiker may indicate assembly

sites from the Viking Age or even earlier

(Fig. 11). The neighboring farm west of Berg is

called Skjøl, ON Skeiðiholf, a name interpreted as

“height used for horse races” (Rygh 1914:261–262).

East of the certain thing site at Sanden is the farm of

Horgen, a name that could be interpreted as pagan

cult site (Rygh 1914:270–271). The same interpretation

has been put forward for Hovet, a small-holding

located east of Varlo, dated to the Viking Age

(Sandnes and Stemshaug 1976:30). The place-names

thus indicate communal Viking Age meeting-places

Table 1. Landowners and land rent of the farms with assemblies

in Eiker. The land rent showing the fiscal values of the farms in

Eiker, where Sanden and Varlo were considered large farms and

Fiskum was categorized as a medium fiscal unit (Cf. Fladby and

Imsen 1971).

Farm Ownership Land rent

Sanden Farmer Large

Hedenstad Royal Unknown

Berg Unknown Unknown

Haug Church Unknown

Varlo Farmers and aristocracy Large

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

53

near Berg, Sanden, and Varlo.

Another interesting name in Eiker is Vegu,

ON Víghaugar, a farm located near the southern

skipreiða boundary (Fig. 11). The first part of the

name, vig n., has been interpreted as “battle, murder”,

or ON vé n. “sanctuary”, and the last part

comes from a mound (haugr) (Rygh 1914:275).

Thus, the name may mean “murder mound” or “the

Figure 10. The farm boundaries of Berg and Sem in Eiker skipreiða.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

54

Figure 11. The figure shows the location of weapon finds and hoards from the Iron Age in relation to the thing sites at Eiker

skipreiða, as well as place-names indicating cult-sites. The weapon graves are modified after Mikkelsen 2006:22.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

55

2005:63–68). Consequently, new administrative

requirements were created, and it is likely that they

were dealt with at the fylkir-churches. Around the

beginning of the 13th century, the skipreiður appear

in the sources as fixed tax districts. It is, likely,

however, that they were based on older Danish

herað divisions, which again could be based on natural

boundaries between rural districts (Jørgensen

1974:235, Norseng and Stylegar 2003:484). It is

therefore possible that, at least some local assemblies

retained their location throughout the Middle

Ages and perhaps even earlier.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the Borgarthing

law area seems to have consisted of two

smaller legislative areas (lagsogn) with two royal

officials (lǫ gmaðr), a situation which could reflect

older conditions. However, later in the same century,

the Borgarthing law area was already extended

and at the same time split up into several lagsogn.

A common feature is the contiguity of assemblies

with royal residences, especially places where royal

officials lived (Seip 1934:16, 33).

Strong royal power is perhaps further reflected

in the Law of the Borgarthing, probably written

down in the first half of the 11th century (Halvorsen

2008, Riisøy 2009:10). The law describes three

types of churches, where the fylkir-churches appear

to constitute the highest level in the hierarchy (B 8;

Halvorsen 2008:133–135). The king’s sanctions for

not paying the fines on time were more severe in the

Borgarthing area compared to the other law areas in

Norway. Within four months of non-payment, the

king had the right to carry out a military campaign

to force all remaining pagans to become Christian

and take their goods in war tribute (B 8.5; Halvorsen

2008:133–134).11 This paragraph is unique to the

Borgarthing area, and the Swedish church historian

Gunnar Smedberg (1973:42) argued that this indicates

that the king had a special connection to the

fylkir-churches in this area. It was moreover also

in the Borgarthing area that the king had the right

to take ownership of private churches if the owner

failed to maintain it (B 8.11; Halvorsen 2008:135).12

A different distribution of the fines if someone

was sentenced to outlawry additionally emphasizes

the king’s strong position in the Borgarthing area.

In all four Norwegian law areas, the bishop had the

right to all fines up to the value of three marks, and

the difference among them lies in the distribution of

the outlaws’ properties and possessions worth more

than that sum. The bishop received the additional

fines in the Frostathing law area, the bishop and king

would split the values above three marks evenly in

the Gulathing law area, and the king, bishop, and

holy mound”. It has been suggested that the name

refers to a cult site (Moseng 1994). As the site is

located on the administrative border, it may as well

refer to an execution site. In both England (Reynolds

1999:108, 2008) and the Borgarthing area, execution

sites were often located at or near administrative

borders and at the fringe of settlements. As no other

sources refer to an execution site, this could, however,

be debated.

Increased Royal Control over the Assembly

Organization?

On a regional level, the name of the law area,

Borgarthing, shows that the town of Borg was the

legal center when the lawthing was established

(Norseng 2005:64).10 It is possible that King Olaf

II Haraldsson established the thing simultaneously

with the foundation of the town of Borg at beginning

of the 11th century. The royal officials, sýslumaðr,

appear in the sagas from the 10th and 11th centuries

(Norseng 2005:61–62). The centers of the sýslar

were connected to the fylkir-churches, which may

date to the 11th century, built on royal land near

new medieval towns, like Borg and Konghelle.

As no assemblies are known from the fylki-level,

it is possible that the sýsla-assemblies were new

establishments, reflecting changes in assembly location

to royally controlled farms. The sýsla areas

and functions might thus have broken with older

administrative units. In the beginning, however, the

borders of the administrative areas may have been

unstable (Helle 1964, Seip 1934, Stylegar and Norseng

2003). It is likely that the king used Christianity

for strategic purposes, to gain control over law and

religion, and as an effort to gain control over society

and local magnates’ power over the judicial and

legal landscape (cf. Brendalsmo 2006). Thus, the

11th century may have been a period that witnessed

fundamental changes regarding the administrative

and assembly institution in the Borgarthing law area,

at least on a regional level.

However, already after the mid-12th century,

the royal officials of the sýsla appear in laws and

documents as administrative leaders of permanent

districts. They had three main duties: law, defense,

and economy (Andersen 1982b:645–648; Helle

1964:145, 2001:152). It has been assumed that one

reason for the royal appointment of offices and fixed

districts can be found in the civil wars between 1130

and 1240, which created a need for royal officials

with armies to control the newly conquered areas,

as well as for more men and income to support

the leiðangr fleet (Helle 1964:145–146, Norseng

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

56

“farmers” would take 1/3 each in the Eidsivathing

district. In the Borgarthing area, on the other hand,

the king had the right to take everything above the

three marks (Spørck 2009:153). This may indicate

that the king had more control in the Borgarthing law

area than in the rest of the kingdom, while the church

was stronger in the Frostathing law area (Spørck

2009:153).

The explanation for the strong royal power in

Viken may relate to the different political affiliations

here and Danish attempts of supremacy through

large parts of the Viking Age until the 13th century,

which may have led to special administrative and

judicial relations in the area. Consequently, when the

Norwegian kings secured the area, they may have

seized control with a grip that was felt even at the

lowest levels, with a system that made it easier to

interfere more effectively in local communities. It is

likely that the king used Christianity strategically in

this attempt, as a way to get control of both religious

and legal life. Obviously, the royal consolidation

of power and institutionalization of the assembly

organization was a continuing process, although it

seems that larger changes can be identified at the

higher administrative levels around the 11th century

and between the mid-13th and 14th centuries.

Royal Influence in Eiker skipreiða?

In sources from the 16th century, Eiker was

divided into four fjórðungar: Fiskum, Hedenstad,

Sanden, and Varlo (Fig. 12). A thing site at Varlo is

indicated but only by its name. Haug was originally

categorized as a possible thing site; however, this

could probably be linked to Haug’s status as an important

ecclesiastical arena for announcements and

written transactions and contracts.

That leaves the other two other possible thing

sites in the same fjorðung as Haug, namely Varlo

and Berg, which most likely indicate that changes

occurred in the location or functions of one of the

sites. Even though one should be careful not to infer

ex silentio, the fact that Varlo is not recorded as a

thing site in medieval documents might indicate

that the assembly was moved from Varlo to Berg.

The transferral of the assembly may have happened

before the mid-14th century, which is when the

first diploma indicating legal functions at Berg is

dated (DN III:299; 300, 1358–9; Lange and Unger

1853:243, 244). After 1273, documents started being

more commonly produced at thing meetings, especially

concerning cases with physical injuries (RN

II:112; Bjørgo and Bagge 1978:70). The growing

use of written documents for judicial acts led to increasing

participation of both central and local royal

officials in cases in the legal districts (Dørum 2004:

387). As stated above, thing meetings at Berg are

repeatedly referred to as weapon things, designating

assemblies on the skipreiða level. The question then,

is why the assembly was moved to Berg, as there are

no indications of other thing sites in the skipreiða

being moved.

As mentioned above, it has been suggested that

powerful families controlled the thing meetings

(Andersen 1977:255, Imsen 1990:193). None of the

farms with assemblies in Eiker, however, have finds

of prehistoric weapon graves, and as the farms in

the early Modern Period were owned by different

landowners and the land rents of half of the farms

remain unknown, it is difficult to draw any positive

conclusions for this skipreiða. Then again, three of

the farms with assemblies had a medieval church.

In the last decades, several scholars have claimed

that the aristocracy played an important part in establishing

the earliest churches in Scandinavia (e.g.,

Brendalsmo 2006, Emanuelsson 2005:223, Lidén

1995:129–131, Skre 1998:64–72). The church at

Berg may have been a private church, as known

from the Law of the Borgarthing (B8; Halvorsen

2008:133–135).13 Private churches can be seen

as expressions of local continuity of power, in

the same way as the royal churches—such as the

fylkir-churches—from the same period, interpreted

as manifestations of royal supremacy (Brendalsmo

2006:285–287). Considering that Berg’s neighboring

farm has a name suggesting horse racing,

together with a possible private church, it may seem

peculiar that an assembly was not located at Berg

originally. However, place-names and rich archaeological

finds from the farms surrounding Varlo also

testify to the area’s importance in prehistoric times.

The fact that the legal and cultic, and later Christian,

functions are located close together, often on

neighboring farms, is a recurring phenomenon in the

Borgarthing area.

The weapon thing at Berg perhaps suggests a

family of an extraordinary position and higher status

than others. At least, being one of the king’s “faithful

men” may suggest that this farmer had greater influence

over decisions at the assemblies than others

(Moseng 1994:95), while perhaps also giving the

king some control over the thing organization at the

lower level in Eiker. Maybe changing the location

of the thing site, and perhaps also the function, is a

consequence of the king gaining ownership of the

farm of Sem? The date coincides chronologically

with the period when the control of weapons at

the assemblies had, or was in the process of, being

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

57

Figure 12. The investigation area with the certain and possible thing sites. The certain thing site of Berg is suggested as the

main thing for the whole skipreiða, i.e., the weapon thing, located next to the royal farm of Sem.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

58

transformed into a tax (Andersen 1982a:346–359).

Consequently, it is likely that taxes in kind were

collected at the assembly of Berg and moved to

Sem for storage and use. Then again, why not move

the assembly to the royal farm itself? The relation

between assembly sites, chieftain’s and royal farms

is not properlyly understood, and several different

situations have been observed (e.g., Andersen

1977:225, Reynolds 1999:65–110, Sanmark 2011,

Turner 2000). In northern and southwestern Norway,

there seems to be a close connection between

chieftain’s farms and courtyard sites,14 interpreted as

assemblies on neutral ground where the landowning

elite could meet for political and religious activities

(Storli 2000, 2010). This desire for a neutral site

could perhaps explain the location of the weapon

thing at Berg, not directly located on the royal farm

itself, as the “farmer” might have functioned as a

royal official with close connections to the king

and his administration, while at the same time also

serving as local representative and sanctioning the

law for the local population. The royal officials were

dependent on the thing participants’ cooperation,

whilst looking after the king’s interests in the local

communities, for example the collection of taxes.

The thing thus became an arena for cooperation

between the royal representatives and the farmers

(Dørum 2004:387, Imsen 1990:193–198).

Conclusion

Previous researchers have presumed that the king

took strong control over the assembly organization

after the mid-12th century, especially through his

representatives. The development of the administrative

structures and royal administration discussed

in the regional analysis seems to support this view.

Most likely, the king gained more control over the

thing organization by drawing the activities closer

to new urban centers and central administration, at

least at the highest administrative levels. This paper

has examined how power may have been extended

down to the lower levels.

In Eiker, three of the suggested thing sites had

the same location across the centuries, which seems

to imply a continuity of the political system. However,

as shown, the thing system was not static, and

changes both in the thing site location and administrative

districts could happen. The main skipreiða

thing in Eiker was moved to Berg in the 13th century,

probably to be closer to the royal farm of Sem.

This move could probably be related to increased

royal control over the local thing institution and the

judicial life in the districts by the beginning of the

13th century. Nevertheless, the thing was an arena

for the general public in the local communities, and

especially before the 15th century, this was a result

of cooperation between the royal representatives

and the farmers. The thing sites gradually became

an instrument for communication and cooperation

between the local communities and royal authority.

This is, however, a study of only one skipreiða,

and not necessarily representative for the

Borgarthing law province as a whole. This study

is part of the author’s PhD, and these preliminary

results will in the next stage be contextualized

in relation to the rest of the analysis of the law

area, which will contain approximately 10–15 selected

skipreiður in the Borgarthing law area. Even

though some researchers have reflected on the

location of thing sites close to churches and rural

centers, the sites have not previously been studied

from a landscape perspective, nor have they been

compared to administrative boundaries and other

structures. To my mind, this is a fruitful perspective

in the continued study of the administrative

landscape of the past.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Ingvild Øye, Frode

Iversen, Aleks Pluskowski, and Kristin Kausland as well

as the two anonymous referees for valuable comments on

this paper.

Literature Cited

Andersen, P. 1977. Samlingen av Norge og kristningen av

landet 800–1130. Handbok i Norges historie II. Universitetsforlaget,

Bergen, Norway. 382 pp.

Andersen, P. 1982a. Ting. Pp. 346–359, In J. Danstrup et

al. (Eds). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder.

Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag,

1980. Vol. 18. Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Denmark. 723 pp.

Andersen, P. 1982b. Syssel. Pp. 645–648, In J. Danstrup

et al. (Ed.). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder.

Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag,

1980. Vol. 17. Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Denmark. 722 pp.

Andressen, L.T. 1980. Om bruksstørrelse i lys av skyld og

skatt. Pp. 50–58, In R. Fladby and H. Winge (Eds.).

Den eldste matrikkelen. En innfallsport til historien.

Skattematrikklen 1647. Skrifter fra Norsk lokalhistorisk

institutt 7, Oslo, Norway. 79 pp.

Austad, I. 1974. Eikerbygda. Historisk bok om Eiker.

Harald Lyche and Co. A.s. Drammen, Norway. 134 pp.

Bjørgo, N., and S. Bagge (Eds. and Trans.) 1978. 1264–

1300. 435 pp, In Regesta Norvegica: Kronologisk

Fortegnelse over Dokumenter vedkommende Norge,

Nordmænd og den norske Kirkeprovins (1898–), Vol.

2. Norsk historisk kjeldeskrift-institutt. Riksarkivet,

Christiania, Norway. ≈5000 pp.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

59

Bjørkvik, H. 1968. Det norske krongodset i reformasjonshundreåret.

Unpublished manuscript. Trondheim,

Norway. 341 pp.

Bjørkvik, H. 1981. Leiðangr. Pp. 432–442, In J. Danstrup

et al. (Ed.). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder.

Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag,

1980. Vol. 10, Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Denmark. 719 pp.

Bjørkvik, H. 1982. Skipreide. Pp. 546–551, In J. Danstrup

et al. (Ed.). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder.

Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag,

1980. Vol. 15, Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Helsingfors, Reykjavík, Oslo, Stockholm.723 pp.

Bjørkvik, H. and A. Holmsen. 1978 (1952–1954). Kven

åtte jorda i den gamle leiglendingstida? Fordelinga av

jordeigedom i Noreg 1661. Samling av artikkelrekke

publisert i Heimen IX. Tapir, Trondheim, Norway.

104 pp.

Brendalsmo, J. 2006. Kirkebygg og kirkebyggere. Byggherrer

i Trøndelag. Ca. 1000–1600. Unipub forlag.

Oslo, Norway. 706 pp.

Brink, S. 2004. Legal assembly sites in early Scandinavia.

Pp 205–216, In A. Pantos and S. Semple (Eds.). Assembly

Places and Practices in Medieval Europe. Four

Courts Press, Dublin, Ireland. 251 pp.

Brink, S., O. Grimm, I. Iversen, H. Hobæk, M. Ødegaard,

U. Näsman, A Sanmark, P. Urbanczyk, O. Vésteinsson,

and I. Storli. 2011. Court sites of arctic Norway:

Remains of thing sites and representations of political

consolidation processes in the northern Germanic

world during the first millennium AD? Norwegian

Archaeological Review 44(1):89–117.

Bugge, A. 1918. Tingsteder, gilder og andre gamle mittpunkter

i de norske bygder. Historisk Tidsskrift V R,

IV:97–152, 195–252.

Bull, E. 1918. Studier over Norges administrative inddeling

i middelalderen. Historisk Tidsskrift V R,

IV:257–282

Bull, E. 1920. Leding. Militær- og Finansforfatning i

Norge i ældre tid. Steenske Forlag, Kristiania og København,

Denmark. 175 pp.

Bull, E. 1924. Stevne. Historisk Tidsskrift 5 R, VI:30–145.

Bull, E. 1930. Fylke. Scandia 3:78–105.

Dørum, K. 2004. Romerike og riksintegreringen. Integreringen

av Romerike og det norske rikskongedømmet

i perioden ca. 1000–1350. Acta Humaniora. Series of

dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Arts, University

of Oslo. No. 183. Unipub, Oslo, Norway. 605 pp.

Eithun, B., M. Rindal, and T. Ulset (Eds. and Trans.) 1994.

Den eldre Gulatingsloven. Norrøne tekster 6, Riksarkivet,

Oslo, Norway. 208 pp.

Emanuelsson, A. 2005. Kyrkojorden och dess ursprung.

Oslo biskopsdöme perioden ca. 1000–ca. 1400. Avhandlinger

frånd Historiske institutionen. Göteborgs

Universitet, 44. Göteborg, Sweden. 339 pp.

Ersland, G.A. 2000. Kongshird og leidangsbonde. Pp.

13–154, In G.A. Ersland and T.H. Holm (Eds.). Norsk

Forsvarshistorie, bind 1. Krigsmakt og Kongemakt

900–1814. Eide Forlag, Bergen, Norway. 335 pp.

Farbregd, O 1984. Gardsgrenser og geometrisk analyse.

Teori og metodiske prinsipp. Heimen 1(XXI):33–50.

FitzPatrick, E. 2004. Royal inauguration mounds in medieval

Ireland: Antique landscape and tradition. Pp.

44–72, In A. Pantos and S. Semple (Eds.). Assembly

Places and Practices in Medieval Europe. Four Courts

Press, Dublin, Ireland. 251 pp.

Fladby, R., and S. Imsen (Eds.) 1971. Skattematrikkelen

1647, bind V. Buskerud fylke, Norsk Lokalhistorisk

Institutt, Universitetsforlaget, Oslo, Norway. 196 pp.

Gjermundsen, J.O. 1980. Hvor langt kan vi stole på Skattematrikkelen?

Pp. 87–109, In R. Fladby and H. Winge

(Eds). Den eldste matrikkelen. En innfallsport til

historien. Skattematrikkelen 1647. Skrifter fra Norsk

lokalhistorisk institutt 7. Oslo, Norway. 79 pp.

Gjessing, C.S. 1857. Amtskart. Kartverket, Hønefoss

(Norwegian Mapping Authority): Buskerud amt, 1:200

000, nr 21. Unpublished material. Available from

Kartverket at http://www.kartverket.no.

Grieg, S. 1980. Budstikke (eller budkavl). Pp. 338–340, In

J. Danstrup et al. (Eds). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for

Nordisk Middelalder. Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid.

2. opplag, 1980. Vol. 2, Rosenkilde og Bagger,

København, Denmark. 687 pp.

Halvorsen, E.F. (Trans.) 2008. Borgartings eldre kristenrett,

versjon 1, etter AM 78 4°. Pp. 119–159, In

E.F. Halvorsen and M. Rindal (Eds and Trans.). De

eldste østlandske kristenrettene. Norrøne tekster nr. 8.

Riksarkivet, Oslo, Norway. 231 pp.

Hasund, S. 1921. Leidingen og maanadsmaten. Syn og

Segn, bd. 27.

Helle, K. 1964. Norge blir en stat 1130–1319. Universitetsforlaget,

Bergen, Norway. 211 pp.

Helle, K. 2001. Gulatinget og Gulatingslova. Skald, Leikanger,

Norway. 240 pp.

Hertzberg, E. 1874. Grundtrækkene i den ældste norske

proces. I kommission hos Aschehoug, Kristiania,

Norway. 279 pp.

Hertzberg, E. 1914. Ledingsmandskabets størrelse i Norges

middelalder. Historisk Tidsskrift 5.R. II:241–276.

Hofseth, E.H. 1981. Loven om våpenting sett i lys av

arkeologisk materiale. Pp. 103–118, Universitetets

oldsaksamlings årbok 1980–81. Universitetets oldsakssamling,

Oslo, Norway. 211 pp.

Holmsen, A. 1940–1942. Nye metoder innen en særskilt

gren av norsk historieforskning. Historisk Tidsskrift

32:27–45.

Imsen, S. 1990. Norsk bondekommunalisme fra Magnus

Lagabøte til Kristian Kvart. Del 1. Middelalderen.

Tapir forlag, Trondheim, Norway. 226 pp.

Iversen, F. 1999. Var middelalderens lendmannsgårder

kjerner i elder godssamlinger? En analyse av romlig

organisering av graver og eiendomsstruktur i Hordaland

og Sogn og Fjordane. Arkeologiske avhandlinger

og rapporter fra Universitetet i Bergen 4, Bergen,

Norway. 78 pp.

Iversen, F. 2008. Eiendom, makt og statsdannelse. Kongsgårder

og gods i Hordaland i yngre jernalder og middelalder.

UBAS Universitetet i Bergen Arkeologiske

skrifter 6. Nordisk, Bergen, Norway. 416 pp.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

60

Iversen, F. 2013. Concilium and Pagus—Revisiting

the Early Germanic Thing System of Northern Europe

Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume

5:5–18.

Indrebø, G. 1935. Fjorðung. Granskingar i eldre norsk

organizasjons-soge. Bergens Museums Årbok 1935.

Historisk-antikvarisk rekke nr. 1. Bergen, Norway.

287 pp.

Johnsen, N. 1914. Eker. Træk av en storbygds saga. Utgit

ved Konunal Foranstaltning, Kristiania, Norway. 655

pp.

Jónsson, F (Ed.) 1902–1903. Fagrskinna. Nóregs Kononga

Tal, III. Møller. København, Denmark. 415 pp.

Jørgensen, P.J. 1974. Dansk retshistorie: Retskildernes og

forfatningsrettens historie indtil sidste halvdel af det

17. aarhundred. G.E.C. Gad, København, Denmark.

590 pp.

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1847. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen, vol. 1:1,

Christiania, Norway. 384 pp.

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1851. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen, vol. 2:1,

Christiania, Norway. 416 pp.

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1852. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen, vol. 2:2,

Christiania, Norway. 531 pp.

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1853. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen, vol. 3:1,

Christiania, Norway. 400 pp.

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1857. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen, vol. 4:1,

Christiania, Norway. 384 pp.

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1858. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen, vol. 4:2,

Christiania, Norway. 523 pp

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1860. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen, vol. 5:1,

Christiania, Norway. 523 pp.

Lange, C.A., and C.R. Unger (Eds. and Trans.) 1861. Diplomatarium

Norvegicum. Oldbreve til Kundskab om

Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog, Slægter, Sæder,

Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen vol. 5:2,

Christiania, Norway. 531 pp.

Larsson, M.G. 1998. Runic inscriptions as a source for

the history of settlement. Pp. 639–649, In K. Düwel

and S. Nowak (Eds.). Runeninschriften als Quellen

interdisziplinärer Forschung, Abhandlungen des

vierten internationalen Symposiums über Runen und

Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4.-9. August 1995.

Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen

Altertumskunde 15. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany.

812 pp.

Lidén, H.-E. 1995. De tidlige kirkene. Hvem bygget dem,

hvem brukte dem, og hvordan? Pp. 129–141, In H.-E.

Lidén (Ed.). Møtet mellom hedendom og kristendom

i Norge. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo, Norway. 300 pp.

Lunden, K. 1965. Mellemalder. Pp. 149–311, In J.N.

Bolstad, J. Grønset, H. Haugerud, O.H. Mysen, G.

Natrud and I.R. Manum (Eds.). Heggen og Frøland.

Fellesbind for bygdene Askim, Eidsberg og Trøgstad.

Øvre Smaalenene - Askim Boktrykkeri, Askim, Norway.

377 pp.

Martens, I. 2003. Tusenvis av sverd. Hvorfor har Norge

mange flere vikingtidsvåpen enn noe annet europeisk

land? Collegium Medievale 16:51–66.

Mikkelsen, E. 2006. History of the Find and its Environment.

Pp. 29–54, In I. Fuglesang and D.M. Wilson

(Eds.), The Hoen Hoard. A Viking gold treasure of the

ninth century. Norske Oldfunn XX. Kulturhistorisk

Museum, Universitetet i Oslo. Oslo, Norway. 340 pp.

Moseng, O.G. 1994. Sigden og Sagbladet. Eikers historie

- Bind II. Øvre og Nedre Eiker kommuner. Hokksund,

Norway. 349 pp.

Munch, P.A. 1846. Norges Love ældre end Kong Magnus

Haakonssøns Regjerings-Tiltrædelse i 1263. Pp. 468,

In R. Keyser and P.A. Much (Eds). Norges gamle

Love indtil 1387, vol. I–IV (1846–1895). Christiania,

Norway. 2962 pp.

Myking, J.R. 2007. Peasant participation in local thing

and conflict handling institutions in Norway from the

13th century to the end of the Early Modern Period. Pp.

187–204, In T. Iversen, J.R. Myking, and G. Thoma

(Eds). Bauern zwischen Herrschaft und Genossenschaft..

Tapir Academic Press, Trondheim, Norway.

289 pp.

Norseng, P. 2005. I Borgarsysle. Pp. 12–334, In P. Norseng

and S.G. Eliassen (Eds.). I Borgarsysle. Østfolds

historie, bind 2. Østfold Fylkeskommune, Sarpsborg.

504 pp.

Opstad, L. 1976. Olav Haraldsons by. 1016–1567. Pp.

117–296, In E. Johnsen, L. Opstad, and M. Dehli

(Eds.). Sarpsborg før 1839. Sarpsborg Kommune,

Sarpsborg, Norway. 440 pp.

Pantos, A., and Semple, S. (Eds.) 2004. Assembly Places

and Practices in Medieval Europe. Four Courts Press,

Dublin, Ireland. 251 pp.

Reynolds, A. 1999. Later Anglo-Saxon England: Life and

Landscape. Tempus, Gloucestershire, UK. 192 pp.

Reynolds, A. 2008. The emergence of Anglo-Saxon judicial

practice: The message of the gallows. Agnes Jane

Robertson Memorial Lectures on Anglo-Saxon Studies

1. The Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies, University

of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK. 61 pp.

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

61

Riisøy, A.I. 2009. Sexuality, law, and legal practice and

the reformation in Norway. In The Northern World

monograph series, vol. 44. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands.

212 pp.

Robberstad, K. 1981. Odelsrett. Pp.493–499, In F. Hødnebø

(Ed.). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder.

Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag,

1980. Vol. 12, Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Denmark. 723 pp.

Rosén, J. Landsting. Pp. 293–294, In J. Danstrup et al

(Eds.). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder.

Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag, 1980.

Vol. 10, Rosenkilde og Bagger, København, Denmark.

719 pp.

Rygh, O. 1914. Bratsberg amt. Pp. 528, In O. Rygh and A.

Kiær (Eds.). Norske Gaardnavne: Oplysninger samlede

til Brug ved Matrikelens Revision vol. 4. Fabritius,

Kristiania, Norway.

Sandnes, J. 1969. Fylkeskirkene i Trøndelag i middelalderen.

En del notater og detaljmateriale. Årbok for

Trøndelag, 1969. Laget, Trondheim, Norway.

Sandnes, J. 1982. Tingsted. Pp. 379–381, In J. Danstrup

et al (Eds). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder.

Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag,

1980. Vol. 18, Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Denmark. 723 pp.

Sandnes, J., and O. Stemshaug 1976. Norsk Stadnamnleksikon.

Det norske samlaget, Oslo, Norway. 359 pp.

Sanmark, A. 2009. Administrative organization and

state formation: A case study of assembly sites in

Södermanland, Sweden. Medieval Archaeology

53:205–241.

Sanmark, A. 2011. Archaeological analysis and mapping

in the identification of assembly sites. Norwegian Archaeological

Review 44(1):99–101

Sanmark, A., and S. Semple. 2010. The topography of

outdoor assembly in Europe with reference to recent

field results from Sweden. Pp. 107–119, In H. Lewis

and S. Semple (Eds.). Perspectives in Landscape Archaeology.

Papers presented at Oxford 2003–20055.

BAR International Series 2103. Archaeopress, Oxford,

UK. 119 pp.

Seip, D.A. 1980. Borgarting. Pp. 148–149, In J. Danstrup

et al. (Eds). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk

Middelalder. Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid. 2. opplag,

1980. Vol. 2, Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Denmark. 687 pp.

Seip, J.A. 1934. Lagmann og lagting i senmiddelalderen

og det 16de århundre. Skrifter II. Hist.-filos. klasse

1934. No 3. Jacob Dybwad, Oslo, Norway. 131 pp.

Skre, D. 1998. Herredømmet, bosetning og besittelse på

Romerike 200–1350 e. Kr. Acta Humaniora 32. Det

humanistiske fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo, Universitetsforlaget,

Oslo, Norway. 366 pp.

Skre, D. (Ed.) 2007. Kaupang In Skiringssal. Norske Oldfunn,

Kaupang Excavation Project 22 Vol 1. Åarhus

University Press, Århus, Denmark. 502 pp.

Smedberg, G. 1973. Nordens första kyrkor. En kyrkorättslig

studie. Biblotheca Theologiae Practicae, Vol. 32.

CWK Gleerups Förlag Lund, Lund, Sweden. 230 pp.

Sogner, S.B. 1981. Herred. Pp. 492–494, In J. Danstrup

et al. (Eds). Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk

Middelalder. Fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid.

2.opplag,1980. Vol.6. Rosenkilde og Bagger, København,

Denmark. 711 pp.

Spørck, B.D. 2009. Nyere norske kristenretter (ca. 1260–

1273). Thorleif Dahl kulturbibliotek, Oslo, Norway.

206 pp.

Steinnes, A. 1929. Kor gamal er den norske leiðangrsskipnaden?

Syn og Segn 35:49–65.

Steinnes, A. 1933. Gamal skatteskipnad i Noreg. Avhandlinger

utgitt av Det norske vitenskapsakademi i Oslo

II. Historisk-filosofisk klasse. 3. A.W. Brøggers boktrykkeri,

Oslo, Norway. 228 pp.

Steinnes, A. 1955. Husebyar. I kommisjon hjå Grøndahl

and Søn. Oslo, Norway. 244 pp.

Storli, I. 2000. Barbarians’ of the north: Reflections on

the Establishment of courtyard sites in North Norway.

Norwegian Archaeological Review 33(2):81–103.

Storli, I. 2010. Court sites of artic Norway: Remains of

thing sites and representations of political consolidation

processes in the northern Germanic world during

the first millennium AD? Norwegian Archaeological

Review 43(2):128–144.

Storm, G. 1877. En levning af den ældste bog i den norrøne

litteratur. Historisk Tidsskrift R.1 (4):478–484.

Sturluson, S. 1979. Olav den Helliges saga. Ch. 251, In

A. Holtsmark and D.A. Seip (Eds. and Trans.). Norges

kongesagaer 1 and 2, 1979. Gyldendal Norske Forlag,

Oslo, Norway. 344 pp.

Stylegar F-A. and P.G. Norseng, 2003. Mot historisk tid.

Del II. Pp. 278–512, In E.A. Pedersen, F.-A. Stylegar

and P.G. Norseng (Eds.). Øst for Folden. Østfolds

historie, bind 1. Østfolds fylkeskommune, Sarpsborg,

Norway. 550 pp.

Taranger, A. 1887. Om Betydningen av Herads og

Herads-Kirkja i de ældre Kristenretter. Historisk Tidsskrift

2 R. 6:337–401.

Taranger, A. (Eds. and Trans) 1915. Magnus Lagabøters

landslov. Universitetsforlaget. Oslo, Norway. 206 pp.

Taranger, A. 1935. Innledning - Rettskildenes historie.

Utsikt over den norske retts historie. Bind 1. Oslo,

Norway. 102 pp.

Thomle, E.A. (Eds. and Trans.) 1987. Dombog for 1613,

2, Herredagen paa Eker; Dombog for 1616. Pp. 273,

In E.A. Thomle and P. Groth (Eds. and Trans.), Norske

Herredags-Dombøger, Anden Række (1607–1623).

Det Norske historiske Kildeskriftfond, Norway.

Tunberg, S. 1911. Studier rörande Skandinaviens äldsta

politiska indelning. Uppsala, Sweden. 232 pp.

Turner, S. 2000. Aspects of the development of public assembly

in the Danelaw. Assemblage 5:1–13.

Unger, C.R., and H.J. Huitfeldt-Kaas (Eds. and Trans.)

1863. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Oldbreve til

Kundskab om Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog,

Slægter, Sæder, Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen,

vol. Vol. 6:1, Christiania, Norway. 400 pp.

Unger, C.R., and H.J. Huitfeldt-Kaas (Eds. and Trans.)

1864. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Oldbreve til

Kundskab om Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog,

Slægter, Sæder, Lovgivning og Rettergang i MiddeM.

Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

62

lalderen, vol. Vol. 6:2, Christiania, Norway. 503 pp.

Unger, C.R., and H.J. Huitfeldt-Kaas (Eds. and Trans.)

1867. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Oldbreve til

Kundskab om Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog,

Slægter, Sæder, Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen,

vol. Vol. 7:1, Christiania, Norway. 416 pp.

Unger, C.R., and H.J. Huitfeldt-Kaas (Eds. and Trans.)

1869. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Oldbreve til

Kundskab om Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog,

Slægter, Sæder, Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen,

vol. Vol. 7:2, Christiania, Norway. 499 pp.

Unger, C.R., and H.J. Huitfeldt-Kaas (Eds. and Trans.)

1874. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Oldbreve til

Kundskab om Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog,

Slægter, Sæder, Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen,

vol. Vol. 8:2, Christiania, Norway.507 pp.

Unger, C.R., and H.J. Huitfeldt-Kaas (Eds. and Trans.)

1882. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Oldbreve til

Kundskab om Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog,

Slægter, Sæder, Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen,

vol. Vol. 11:1, Christiania, Norway. 416 pp

Unger, C.R., and H.J. Huitfeldt-Kaas (Eds. and Trans.)

1889. Diplomatarium Norvegicum. Oldbreve til

Kundskab om Norges indre og ydre Forhold, Sprog,

Slægter, Sæder, Lovgivning og Rettergang i Middelalderen,

vol. Vol. 13:1, Christiania, Norway. 416 pp.

Wilson, D.M. 2006. Introduction and summary. Pp.

13–28, In I. Fuglesang and D.M. Wilson (Eds.). The

Hoen Hoard. A Viking gold treasure of the ninth century.

Norske Oldfunn XX. Kulturhistorisk Museum,

Universitetet i Oslo. Oslo, Norway. 340 pp.

Zachrisson, T. 1994. The Odal and its manifestations in the

landscape. Current Swedish Archaeology 2:219–238.

Þorðarson, S 1979. Håkon Håkonssons saga. Ch. 333, In

F. Hødnebø (Eds. and Trans.). Norges kongesagaer 4,

1979. Gyldendal Norske Forlag, Oslo, Norway. 390

pp.

Endnotes

1For this area, only one historical map is used, a so-called

Amtskart from 1857 (Gjessing 1857).

2Elve-, Ranrike-, Borgar,- Oslo-, Tunsberg- and Skiens-

sýsla. Later, Numedal, Telemark, Tverrdalane, and

Modum might have been added to the law area (Helle

2001:152).

3Berg—e.g., DN III:298, 1359 (Lange and Unger

1853:242–243); DN VI:451, 1434 (Unger and Huitfeldt-

Kaas 1864:475–476), NHD 2 r. III (2):25, 1611

(Thomle 1987:25). Sanden—e.g., DN V:372, 1396

(Lange and Unger 1860:269–270; references to more

unprinted diplomas, dated to 1591 and 1604, in Indrebø

1935:140). Hedenstad—e.g., DN VII:378, 1425

(Unger and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1867:372); DN 494, 495,

500, 1445 (Unger and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1864:518–520,

524-525); DN VII:783, 1531 (Unger and Huitfeldt-Kaas

1869:729–730).

4Fiskum: e.g., DN III:337, 1364 (Lange and Unger

1853:265–266); DN VI:410, 1421 (Unger and Huitfeldt-

Kaas 1864:439); Haug: e.g., DN II:428, 1373 (Lange and

Unger 1851:331–332); DN XIII:35, 1378 (?) (Unger and

Huitfeldt-Kaas 1889:29–30); DN XI:214, 1462 (Unger

and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1882:185–186); DN II: 796, 1452

(Lange and Unger 1852:598).

5One diploma was issued at Varlo in the 14th century, but

such activity is not uncommon, and does not in itself

indicate that Varlo was a thing site (DN VI:343, 1394;

Unger and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1863:383).

6Fiskum—living room: DN II:654, 1420 (Lange and

Unger 1852:487); church yard: DN VI:410, 1431 (Unger

and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1864:439); Haug—DN II: 428,

1373 (Lange and Unger 1851:331–332); parsonage: DN

XI:214, 1462 (Unger and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1882:185–186);

church: DN II:796, 1452 (Lange and Unger 1852:598);

DN V:850, 1464 (Lange and Unger 1861:616); DN

VIII:785, 1545 (Unger and Huitfeldt-Kaas 1874:831–

832); Berg—living room: DN V:319:1380 (Lange and

Unger 1860:232); church: DN VI:489, 1442 (Unger and

Huitfeldt-Kaas 1864:515–516).

7Information provided by the farmer at Berg in August

2011 (cf. Moseng 1994:90–92).

8The settlement landscape used here is based on modern

cultivated land and settlement areas, and changes might

have happened over time; however, it will still give a

broad picture of the medieval settlement areas.

9The Norwegian farms were fiscally divided into three categories

according to their value; the large farms paid the

most land rent, then the medium farms, and the smallest

valued farms paid the lowest land rent. An overview of

the land rent is given in the cadaster of 1647 (Fladby and

Imsen 1971). It is generally assumed that this cadaster

represents the land rents before the Black Death in the

mid-14th century (Bjørkvik and Holmsen 1978, Holmsen

1940, Iversen 2008, Skre 1998). Main farms belonging

to the priest and aristocracy, like parts of Fiskum, Berg,

and Haug, often had tax exemptions, and thus were not

documented in the cadasters. Regardless of the margins

of error, the land rents can be used as a basis for comparison

of the farms’ economic capacity in the Middle Ages

(Andressen 1980:50, Gjermundsen 1980:37–38).

10A thing in Borg is mentioned several times in the sagas

from the beginning of the 11th century onwards. The term

Borgarthing was not used until Harald Fairhair’s seizure

of power in 1047 (Jónsson 1902–1903:332). The assembly

was, however, not referred to as a lawthing until 1224

(Seip 1980:148–149).

11Nu skall gera hina iiij fiogura manoðr stæfnu. Þa er

sa æin hærnaðr er konongr løyfði innan landz at hæria

monnum till kristins doms. Han skall æigi men drepa oc

æigi hus brenna. Fe þæira | skall han taka oc bu oc hava

at hærnaðe (8.5; Halvorsen 2008:133–134).

12… Gera honom hina .iijjo. manoðr stæfnu. En ef þa

er æigi gor þa a konongr bø þæn en bonde |-er-|ækki

i. Halde konongr upp kirkiv gærð (B8.11; Halvorsen

2008:135).

M. Ødegaard

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

63

13The churches at Fiskum and Haug might also have

been private churches, but this point will not be discussed

here. Archaeological remains have been found

beneath the standing stone church at Haug, interpreted

as an older church, probably a stave church (cf. Moseng

1994:20–25).

14Courtyard sites are interpreted as assembly sites, dated

from the 3rd to 10th centuries. For a discussion see Brink

et al. (2011).