[an error occurred while processing this directive]

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

111

Introduction

To most English speakers, the term “booth”

probably brings to mind telephone-booths, ticketing-

booths, or other such narrow and confined

compartments. The word, however, is derived from

the Old Norse búð, which has a considerably wider

meaning and can refer to a camp or camp-site (esp.

in the plural, as in herbúðir = “military camp”), but

in the singular it normally implies a structure of

solid foundations (if not superstructure) and either

What is in a Booth? Material Symbolism at Icelandic Assembly Sites

Orri Vésteinsson*

Abstract - Booths are a distinctive feature of the assembly sites established in Iceland in the Viking Age. The study of

Icelandic assemblies has a long pedigree. Although there have been significant advances in this field in recent years, the

booths remain enigmatic, both in terms of their dating and their function. In this paper, it is argued that instead of viewing

the booths primarily as functional solutions to the problem of camping in the open, it is more revealing to consider their

symbolic meaning, which can be deciphered on at least two levels. On the political level, the size of the booths, their number,

and their arrangement were determined by the political landscape of each assembly, providing fuel for hypotheses about

political developments in late Viking Age Iceland. On an ideological and mental level, the booths can be seen as symbols

of collective and individual participation in the new social and political structures being created, but also—critically in

landscapes only beginning to acquire cultural signifiers—they served the purpose of marking, and thereby legitimizing, the

assemblies and their functions.

Debating the Thing in the North I: The Assembly Project

Journal of the North Atlantic

*Department of Archaeology, University of Iceland, Sæmundargötu 2, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland; orri@hi.is.

2013 Special Volume 5:111–124

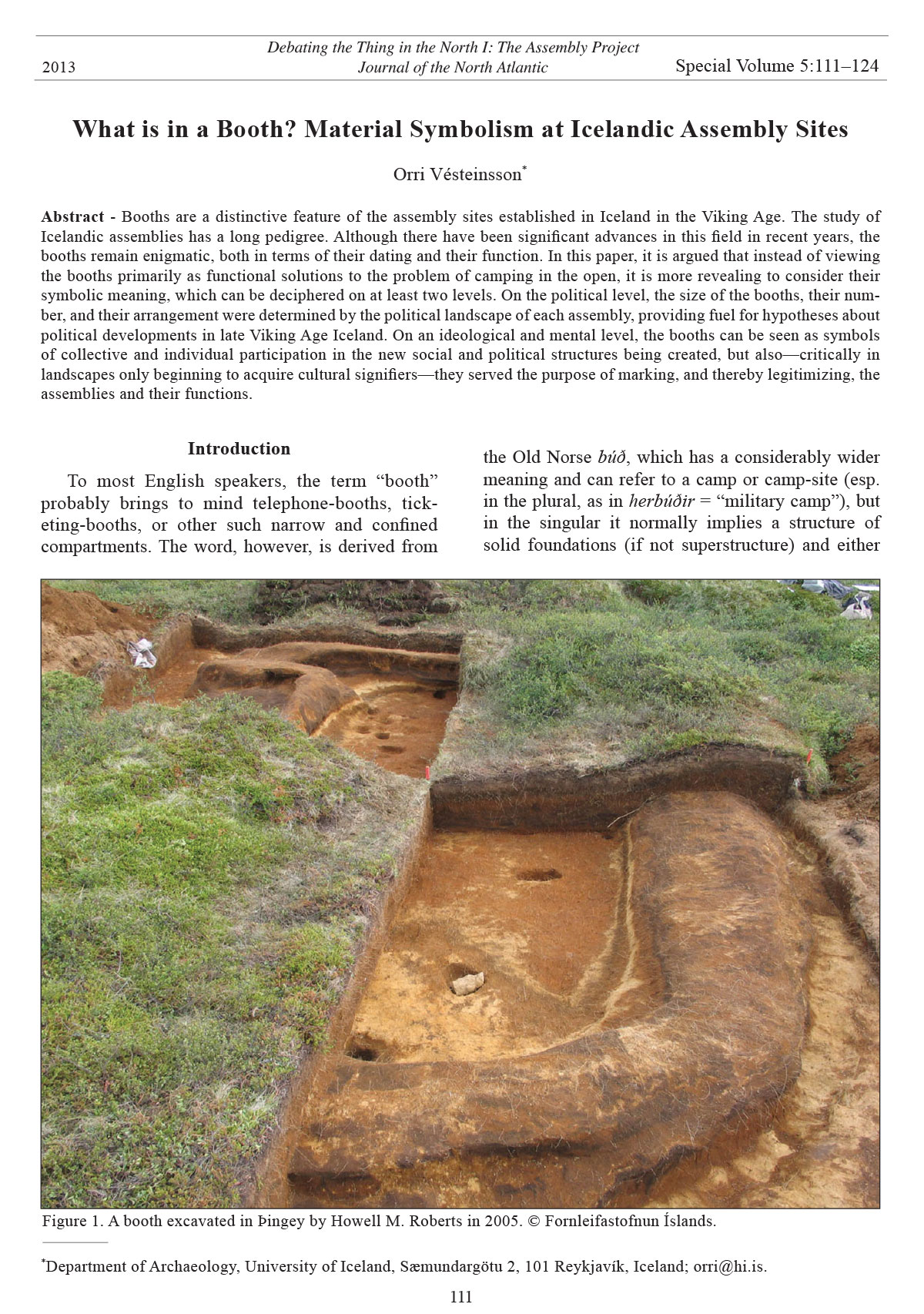

Figure 1. A booth excavated in Þingey by Howell M. Roberts in 2005. © Fornleifastofnun Íslands.

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

112

impermanent or intermittent use (see Ordbog over det

norrøne prosasprog, s.v. búð) (Fig. 1). In the context

of both assemblies and trading sites, a búð seems as

a rule to refer to solid walls of turf (or turf and stone)

which were covered with a tarpaulin or possibly

hides mounted on a light wooden frame raised for the

occasion and taken down again after use. There are

plenty of references in medieval Norse texts to the

booth walls as well as their tent-like covering (Ordbog

over det norrøne prosasprog, s.v. búð, búðartópt,

búðarveggr; s.v. tjald, tjalda, tjaldbúð), and from

these it can be deduced that such booths could be both

large and small and the booths of kings and chieftains

could be richly furnished, although as a rule they

seem to have been rather basic shelters (Stigum 1957,

Weinmann 1994:341–46).

The concept is thus well known and richly documented

since the advent of writing in the Nordic

countries, and the practice also had an unbroken

history, at least in Iceland; the officials who still

met at Þingvellir in the 18th century for the annual

session of the general assembly, the althing, each

had their own booth for which they brought their

tents mounted for the few days that the court was

in session. It is the remains of these early modern

booths that can still be seen at Þingvellir, but they

are also known to cover the remains of earlier structures

of the same character (Friðriksson et al. 2005,

Þórðarson 1945:215–260). When scholarly interest

in the assemblies of the Viking Age and the medieval

period was kindled, booths therefore became

considered to be the features whereby assembly sites

could be identified (Friðriksson 1994:105–145).

Antiquarians working in Iceland in the late 19th and

early 20th century were keen to find the material

traces of the assemblies because this would support

reconstructions of the administrative systems of the

Viking and Saga Ages. In this effort they had considerable

success, documenting a number of sites

which are convincingly associated with the spring

assemblies (Icel. vorþing) mentioned in texts. It

was this particular type of assembly, the 13 regional

assemblies that represent the tier below the national

assembly at Þingvellir, which the antiquarians were

preoccupied with. These assemblies were convened

in spring (Icel. vor) before the general assembly met

at Þingvellir in late June and are considered as an

integral part of the Icelandic judicial system during

the Commonwealth period (930–1262) (Karlsson

2000:20–27). The terms spring assembly and regional

assembly can be used interchangeably, but

strictly speaking, spring assembly refers to the legal

definition, the term vorþing found in the medieval

texts, while regional assembly is an archaeological

definition referring to a site, which, from its

booths and location, can be argued to have served

a region, an area of several hundred farms. In many

cases, the physical remains of regional assembly

sites can be convincingly associated with particular

spring assemblies mentioned in the texts, most

often from place-name evidence, but there are also

spring assemblies which have not been identified

on the ground and some regional assembly sites

which do not fit the judicial structure described in

the medieval texts. The correspondence is, however,

close enough that there is little doubt that in Iceland

several Viking Age and medieval spring assemblies

can be associated with sites where surviving booth

remains are preserved (Vésteinsson 2006a:309–311,

Vésteinsson et al. 2004:177–178). Comparable sites

have not been found elsewhere in the Norse world.

There are textual references to booths at Þinganes in

the Faroes, but no booth remains are to be seen there

(Brøgger 1937:203, Halldórsson 1987:112–123).

For Greenland, suggestions have been made about

two sites which share some similarities with the Icelandic

assembly sites (Sanmark 2010), but these can

also be interpreted differently. In areas of Norse settlement

and influence in the British Isles, assembly

sites are known (see Sanmark 2013 [this volume]),

mostly from place-names, and some have structural

elements (e.g., most famously, Tynwald Hill on the

Isle of Man; Darvill 2004), but nothing resembling

the booths of the Icelandic sites has been recognized

(Crawford 1987:206–210). It is intriguing, however,

that at the Brough of Deerness in Orkney, surely a

supra-local site but one not associated with assembly

functions in the literature, the structures have in their

arrangement a superficial similarity to the Icelandic

assembly sites. Recent excavations indicate that

they are permanent high-status dwellings (Barrett

and Slater 2009), but the large number of similarly

sized and tightly spaced structures, along with the

peripheral location, suggest that this is no ordinary

chiefly residence and that it may share some functional

elements with the Icelandic assembly sites.

In Scandinavia, booths are not a feature of assembly

sites, and there is only a single reference to a booth

at an assembly in Norwegian legal texts (Eithun et

al. 1994:118). At those assemblies associated with

the 10th–13th centuries in Norway, structural remains

are hard to find, and as a result, their actual location

is often uncertain (e.g., Helle 2001:esp. 48–83). The

only possible exceptions are the so-called courtyard

sites, for which several interpretations have been

proposed. A current favorite is that they were assembly

sites (Storli 2010), and there are good reasons to

think that is indeed what they are. However, their

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

113

heyday was before the Viking Age, with most dates

ranging from the 3rd century AD to the early Viking

Age, although a few seem to have been in use into the

10th and even early 11th centuries (Storli 2010:139;

Iversen, in press; an 11th-century date is reported for

Værem in Trøndelag by Onsøien Strøm 2007). Their

distinctive courtyard layout is only faintly echoed in

a couple of the Icelandic sites, and not at all at the

majority. Like the Brough of Deerness, the Norwegian

courtyard sites also tend to reveal much more

substantial remains of human presence and activity

than found at any of the Icelandic sites (e.g., Olsen

2005). There may well be threads—of ideas, sensibilities,

and practices—that connect the Norwegian

courtyard sites with the Icelandic assembly sites, but

as the chronological overlap is tenuous (not least

because it is unclear how early the Icelandic booths

are, see below) and there are distinct differences in

layout and use, these two kinds of sites cannot be

considered as one and the same phenomenon. Even

if the Icelandic booth assemblies represent some sort

of a revival of a more or less obsolete Norwegian

practice, it is not this connection that is most significant

or interesting about them. Rather it is the fact

that this practice had resonance in the new societies

of the North Atlantic. Nothing similar to the booths

has been reported from other parts of Europe in this

period (e.g., Pantos and Semple 2004, Sanmark and

Semple 2008), supporting the view that they are a

feature particular to Iceland, and possibly the new

colonies of the North Atlantic. Although it cannot

be demonstrated, it is likely that assembly sites with

booths also existed in the Faros and Greenland, but

the following discussion will be confined to the Icelandic

evidence.

Preparing the Ground

My contention is that booths at assembly sites

relate to the particular conditions created when

societies are established in previously uninhabited

lands. On the one hand, the political order in such

conditions is likely to be significantly different from

that of the homelands and from those colonies established

among pre-existing populations, and on the

other, the lack of history and permanence of political

structures would have generated a need to create

material representations of power.

This perspective opens up a host of interpretational

possibilities, but first two major shortcomings

of the evidence must be acknowledged. One is the

problem of identification already alluded to. This

concern has seen detailed discussion elsewhere

(Vésteinsson 2006a, Vésteinsson et al. 2004; see

also Friðriksson 1994:105–145), and the present

discussion is limited to those sites which are unambiguous

in their identification. These are sites where

• whole booth clusters have survived and the

booths can be distinguished from other types

of structures, and

• where there is either documentary or placename

evidence supporting the identification

of the site as an assembly.

Sites that meet these criteria are Árnes (Fig. 2),

Leiðvöllur (Fig. 3), and Þingskálar (Fig. 4) in the

south; Hegranes (Fig. 5) in the north; and Leiðarnes

(Fig. 6), Þingey (Fig. 7), and Skuldaþingsey (Fig. 8)

in the northeast. In theory, the spring assemblies

should have been thirteen, and four of these (Árnes,

Þingskálar, Hegranes and Þingey) are among the historically

known spring assemblies, while Leiðvöllur,

Leiðarnes, and Skuldaþingsey have only been identified

on the basis of place-name and archaeological

evidence. Þingvellir, the site of the althing, is in a

category of its own and cannot easily be discussed

along with the spring assemblies, although I propose

that the hypotheses suggested here are also relevant

to it.

The other problem is dating. It can be assumed

that the structures at the assembly sites are earlier

than the 13th century as by then some of the assemblies

had been abolished and others were becoming

only sporadically convened (although some, like

Þorskafjarðarþing, continued to be venues for ad

hoc political meetings [Storm 1888:52, 152, 345,

395]). Narrowing the date range, to see for instance

whether the booths were built at the inception of

the assemblies (in the early or mid-10th century)

or whether they belong to some later stage in their

development, has met with limited success. There

are no radiocarbon dates and no diagnostic artifacts

associated with any of the assembly sites, and despite

the potential of tephrochronology to provide

narrower date ranges, archaeological investigations

in Hegranes, Þingey, and Skuldaþingsey have only

been able to confirm that these sites are medieval.

At Hegranes, a suspected booth was built shortly

after the deposition of the H-1104 tephra (Friðriksson

2004:50–51, 53), but a Christian cemetery on the

site has been shown to have been in use both before

and after 1104; its circular enclosure was built after

1104, predating a larger enclosure encompassing a

part of the site (Friðriksson 2004:47–49, Zoëga and

Sigurðarson 2010:101). At Þingey, a booth predates

the H-1300 tephra (Friðriksson et al. 2005), while at

the adjacent Skuldaþingsey, two booths have been

shown only to predate the V-1477 tephra, while

one of those also post-dates V~940 (Friðriksson et

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

114

al. 2007:8–10, Vésteinsson et al. 2004:176). The

indications from Hegranes are the most revealing,

as they show that booths were being built in the

12th century, but there is not enough evidence to

clarify whether booth building was confined to the

12th century or whether it was ongoing through the

10th–12th centuries and even beyond. Results are

more revealing as to the intensity and length of use.

Two booths in Skuldaþingsey have thick cultural

layers and significant evidence for repairs and rebuilding

(Vésteinsson et al. 2004:176), and the only

fully excavated booth, at Hegranes, had possibly

two building phases in addition to evidence for human

presence both before its building and after its

collapse. This is also the only excavation of a booth

to produce artifacts and an animal bone collection

consistent with short stays provisioned from elsewhere

(Ólafsson and Snæsdóttir 1976). A third booth

excavated in Skuldaþingsey also showed evidence

of repairs of the walls, but here the cultural layer was

ephemeral, although some animal bones were retrieved

(Friðriksson et al. 2007:8–10). In contrast, a

booth excavated in Þingey had no cultural layers and

no signs of repairs (Friðriksson et al. 2005:32–37).

Figure 2. Árnes spring assembly, mapped by Garðar Guðmundsson in 2002. © Fornleifastofnun Íslands.

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

115

The ephemeral nature of the cultural deposits in the

excavated booths is consistent with the interpretation

that they served only as shelters for a few days

annually and had no other functions.

Although the archaeological investigations are

too limited for firm conclusions, the evidence is

consistent with the hypothesis that the booths at the

Icelandic assembly sites were in use for decades

rather than centuries. The post-ca. 940 booth at

Skuldaþingsey suggests that it is quite possible that

booth building did not commence as soon as the assemblies

were established and that they represent a

later development, possibly in the late 10th or early

11th century. If booth building only started in the 11th

century, it would be difficult to account for those

sites which cannot have been a part of the constitutional

system established in the mid-10th century

(e.g., Leiðvöllur, Þingeyri; see Vésteinsson 2009).

For these reasons, and they are quite feeble it must

be admitted, I am inclined to suggest that booths are

a mid- to late 10th-century invention but that they

were used into the 12th century at least.

The Constituency of a Booth

There are a couple of false notions that need to be

dispelled before we go further. One is that booths are

necessary because long distances meant that attendees

could not return to their homes during the night

and/or because weather in the North Atlantic is nasty

and extra good shelter is needed. But booths are not

necessary. There are other solutions to the problem

of accommodation of assembly attendees, and the

Figure 3. Leiðvöllur spring assembly, mapped by Daniel

Bruun in 1902 (Bruun 1928:105). This site was surveyed

again in 2011 by Adolf Friðriksson and Garðar Guðmundsson,

and a new map is in preparation.

Figure 4. Þingskálar

spring assembly, mapped

by Böðvar Þór Unnarsson

in 2006. From Unnarsson

(2006:13).

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

116

those finds also show that tents could be magnificent

structures in their own right (Christensen 1974). A

booth very probably allowed a greater degree of

comfort than the same amount of covering would

simplest one, a tent, would have sufficed if it was

only about providing shelter from wind and rain. The

use of tents in the Viking Age is well attested, most

famously in the Oseberg and Gokstad burials, and

Figure 5. Hegranes spring assembly, mapped by Garðar Guðmunsson in 2003. © Fornleifastofnun Íslands.

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

117

2007) because the booths themselves demonstrate

this quite convincingly: there are too few booths

to account for more than a fraction of all farmers

in each assembly region. There were ≈4000

assembly-tax-paying farmers in Iceland around 1100

(Íslenzk fornrit 1:23), some 300 on average in each

spring-assembly region, which is around 10 times

more than the number of booths found at the springassembly

sites. A booth therefore represents some

social unit above the individual farmer but below the

goðorðsmaðr or chieftain, three of whom convened

each spring assembly. Counting booths is not a riskfree

exercise, and different figures are available

for most of the sites, but on the whole they come

out at between 20 and 40 each (Table 1). It cannot

be demonstrated that all the booths at each site are

contemporaneous, but it can be noted that there is

next to no visible superimposition of booths (unlike

the althing at Þingvellir where booths were rebuilt

permit if the tent was pitched on flat ground, but the

main difference between a booth and a tent is the

much greater visual impact of the former, its greater

materiality and permanence. A booth is therefore

not primarily a practical solution to the problem of

accommodation but rather a material expression,

a symbol, a monument to ideas and ideals. Booth

building would inevitably, once started, become a

symbol of the participation of the booth owners in

the assembly, a symbol of the permanence of that

participation. By building a booth, the owners not

only asserted that they were the equals, or better, of

others who had built booths already, but they also

underlined their commitment to the project of having

an assembly.

The other false notion is that the assemblies were

attended by free farmers on an individual basis.

We do not need to rehearse arguments against this

vision of medieval Icelandic society (Vésteinsson

Figure 6. Leiðarnes spring assembly, mapped by Daniel Bruun in 1907 (Bruun 1928:101).

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

118

for centuries and complex stratigraphies have been

exposed [Friðriksson et al. 2005]), and it is therefore

assumed here that the surface remains at each site

represent functional entities.

The number of booths can be suggested to represent

social units similar in size to those which

gave rise to parishes in the 12th century. It is of

course problematic to decide the size of the regions

from which the spring assemblies were attended,

but where there are clear indications provided by

geography and later administrative units, the correspondence

between the number of booths and

the number of parishes is striking. While it might

be tempting to indulge in special pleading to explain

away the differences, the quality of the data

does not allow this, nor is it necessary—there is

a broad correlation here which is compelling.1 I

would venture a step further and suggest that each

booth may have represented a local community of

5–15 farms (on these see Vésteinsson 2006b). The

majority of such communities later developed into

separate parishes, and they can be reconstructed

through analysis of the parish structure. Such

analysis also suggests that the 10th–11th-century

communities would have been somewhat more

numerous, and more unevenly sized, than the

Figure 7. Þingey spring assembly, mapped by Garðar Guðmundsson in 2004. © Fornleifastofnun Íslands.

Table 1. Numbers of booths (compartments rather than detached structures) at seven Icelandic spring assembly sites, compared to the number

of parishes in each region where plausible reconstructions can be made. Some booths are likely to be missing at Árnes and Leiðvöllur

on account of erosion.

No. of booths: No. of booths:

count of latest maximum count No. of parishes

fieldwork (if different) Latest fieldwork reference in assembly region2

Árnes 24+ 30 Friðriksson 2002:15 36

Þingskálar 45 50 Unnarsson 2006:8, 13, 28 34

Leiðvöllur 26+ 47 A. Friðriksson, Fornleifastofnun Íslands, Reykjavík,

pers. comm.

Skuldaþingsey 33 Vésteinsson et al. 2004:174–175 30

Þingey 17–18 Friðriksson et al. 2004:51 30

Leiðarnes 22 29 Bruun 1928:101

Hegranes 35 80 Friðriksson 2004:40 33

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

119

a man of sufficient status and means to count as

a þingmaðr, the client of a chieftain (Vésteinsson

2007). It was the following of such men that counted

for the chieftains, and the participation of such

men in the founding of a spring assembly would

have been vital for its continued success. The communities

dominated by such men may or may not

have had some organizing structure, but in terms of

realpolitik, they will have consisted of tenants of

the þingmaðr and his own clients, yeomen farmers

of circumscribed social and economic status.

later parishes (Vésteinsson 2006b). The number

of booths should therefore be slightly greater than

the number of parishes in the region from which

the assembly was attended as the parish numbers

derive from a later period (the 14th century) than

the postulated period of use of the booths (10th–12th

centuries). It is theoretically possible that these

communities were egalitarian in nature, but our

knowledge about the social structure of Viking Age

and Medieval Iceland suggests that it is more likely

that each was dominated by a major landlord,

Figure 8. Skuldaþingsey spring assembly, mapped by Garðar Guðmundsson in 2004. © Fornleifastofnun Íslands.

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

120

carried out at the other sites, but looking at the available

maps, it appears that there are greater differences

in size at, e.g., Hegranes and Árnes. The difference

between smallest and largest is definitely greater than

at Skuldaþingsey, and there may also be some groupings

in terms of size. The size of a booth can be seen

to relate to the size of the community it represents or

the status of the local leader (and it is of course likely

that the two are connected: the larger the community,

the greater the status of its leader), but a grouping into

size categories at an assembly site would indicate that

there was some layering among the attendees, that

there were groups of more influential þingmenn distinct

from those of lesser status. It should be expected

that the greater such differences, the more developed

centralized authority had become (Friðriksson 2011).

It is intriguing however, that at none of the sites are

there booths which are substantially larger than all the

others. In other words, there is no evidence for differentiation

in booth size which could help to distinguish

the booths of the chieftains from those of the local

leaders, their followers.

Another indication of groupings, possibly across

the status spectrum, is that at some of the sites the

booths seem to be arranged in rows. This pattern is

least apparent at Skuldaþingsey, but all the other

sites have at least some rows, although it is quite

variable how much this characterizes the whole

layout of each site. At Leiðarnes, practically all the

booths are arranged in three rows, but the booths are

not evenly spaced within each row, possibly suggesting

further sub-groupings. Whether this relates

to some geographical classification, e.g., that all the

leaders from the same valley or sub-region arranged

themselves in the same row or cluster, or some other

kind of political groupings, will be difficult to

determine. Variation in this respect does, however,

suggest that some assemblies were more divided

than others and that some were characterized by

factions permanent and significant enough to affect

the layout of the booths.

All the sites have both simple booths, with single

compartments, or double or more complex ones. At

Þingskálar, Leiðarnes, and Skuldaþingsey, there are

only 2–3 double booths while the majority are single

compartments, and in those cases the double booths

may just reflect the structure of local communities,

e.g., that large communities were subdivided or that

adjacent small ones had close collaboration and that

this extended to their participation in the assembly.

At Hegranes and Þingey, and possibly Árnes and

Leiðvöllur, there is, however, greater clustering with

complexes of booths built together in such a way

that it must have been meaningful whether a local

On this reading, the booths therefore represent

the smallest political units in 10th–11th-century Iceland.

They would then symbolize the participation

of those units in the political and judicial processes

being established, but they also represent the fragmentation

and fragility of that higher level of political

authority which the assembly system was all

about making and maintaining (Vésteinsson 2009).

Each booth symbolizes the limits of the power and

authority of the chieftain or chieftains convening

the assembly, and as such they represent a quite

particular kind of political order: an order where the

highest echelon is made up of a group of regional

leaders whose authority over the next tier down, the

local leaders, is weak and easily contested. I suggest,

therefore, that booths only being found in Iceland,

and perhaps the other new colonies of the North Atlantic,

is a reflection of this political reality, a reality

quite different from the homelands where higher

tiers of central authority were more developed. This

conclusion is paralleled by Frode Iversen’s (in press)

analysis of North Norwegian court-yard sites as assemblies

from the period before the development of

effective royal power, where each booth represented

delegations from local thing districts, the smallest

political areas that can be reconstructed.

Deciphering Patterns

Armed with a hypothesis about what an individual

booth represents—a local leader fronting a

local community—we can then proceed to interpret

what the different patterns in the number, size, and

arrangements of the booths can tell us. It is immediately

apparent that there is considerable variation

even among the small number of sites considered

here. There are differences in how scattered the

booths are, whether they are evenly spaced or arranged

in groups, how many are detached and how

many subdivided, to what degree they line up in

rows, and whether the whole plan of each site seems

to be organic or arranged according to some vision

or principle. However, our understanding of each

site is still too limited to imbue the surface traces of

individual booths with much meaning. Rather, we

have to content ourselves with pointing out general

patterns which further research will have to verify

and expand on.

The most straightforward aspect is that some

booths are larger than others. At Skuldaþingsey, the

largest booth is twice as large as the smallest one,

but in terms of size, the booths form an unbroken

series with no signs of size classes (Vésteinsson et

al. 2004:175). Comparable analyses have not been

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

121

leader resided in such a cluster or in one of the simple

booths scattered around. It is tempting to view

such clusters as representations of political factions,

the grouping of several local leaders behind a single

higher-tier leader, but it can also be seen as a variant

of the row phenomenon and may not reflect more

than an acknowledgment that the leaders from the

same valley could collaborate in building booths; it

does not have to mean that they always collaborated

on other matters.

The problem with applying these insights to individual

sites and trying to characterize them on that

basis is that all the sites are poorly understood. Maps

produced of the sites in the late 19th century are in

many cases quite different from what can be seen

there now, and in those cases, it is difficult to know

whether this is the result of over-interpretation being

replaced by more careful approaches or whether

there have been actual changes at the sites. Some

of the more complex ones, i.e., Árnes, Hegranes,

and Leiðvöllur, have been affected by erosion, and

individual structures may well have disappeared or

become obscured in the meantime. These problems

will only be overcome through comprehensive excavation

of these sites. The unique case of the two

assembly sites on adjacent islands in the river of

Skjálfandafljót—Skuldaþingsey and Þingey—does,

however, present an opportunity to reflect on some

of the implications of the patterns described here.

A Story of Power Consolidation?

Adolf Friðriksson (2011) has suggested that the

different degree of clustering of the booths at the

Icelandic assembly sites represents different stages

in the development of power consolidation in early

Iceland. In such a scheme, sites like Skuldaþingsey,

with evenly sized booths and no structuring in their

location, would represent the earliest stage, while

sites such as Hegranes and Árnes, with booths in

rows and clusters, would represent later stages.

If this interpretation was true, excavation of the

more structured sites should reveal evidence of

earlier, less-structured phases, and the twin sites

of Þingey and Skuldaþingsey, located on adjacent

islands in the same river, allow this kind of model

to be explored in order to evaluate if it is likely at

all. It needs to be stressed that at present there is no

dating evidence available to determine whether the

two sites are from different periods, whether one

succeeded the other, or whether they were in use at

the same time. Indeed, the traditional view is that

the two sites are contemporary and that they represent

different functions. The name Skuldaþingsey

has been seen to indicate that it was the site of the

debt-settling aspect of the assembly (see overview

of explanations in Vésteinsson et al. [2004:174]) but

that would make it the only case of such spatial division

of the assembly functions, and it is difficult to

see why this would have been necessary or practical.

Some possible interpretations have been explored

before (Vésteinsson et al. 2004:178–179), but here

I would like to examine what it would mean if the

assembly was at some point relocated the 1.5 kms

from Skuldaþingsey to Þingey.

The differences between the two sites can be

summed up as Skuldaþingsey having twice as many

booths, which are more evenly sized and evenly

distributed, without any indication of planning

or structuring in the layout of the site. Þingey, in

contrast, has fewer booths, but with a greater size

range, and most of these are arranged in rows and

clustered together in groups of 2–4. Þingey also has

a double boundary wall, which is medieval, although

it is not clear whether it belongs to the assembly

function of the site or some subsequent farming

activity (Friðriksson et al. 2005:28–29). It is in this

context noteworthy that at Hegranes there is also a

boundary enclosing a part of the site dating to the

12th century or later. In that case too a later farm

cannot be ruled out, but it is also possible that these

enclosures are a feature of the final phases of these

spring assemblies, perhaps a measure to demarcate

the legally defined assembly area (a concern reflected

in 13th-century laws and sagas; see Friðriksson

and Vésteinsson [1992:31]). The smaller number of

the booths in Þingey, their more uneven size, and

their greater clustering suggests that a relocation

from Skuldaþingsey could be understood in terms

of power consolidation: that there were fewer participants

(or rather politically significant units); that

their hierarchical order was more pronounced, and

that they were grouped into more distinct factions.

This reading would certainly fit the conventional

view of political developments in Iceland in

the course of the 10th–13th centuries (Sigurðsson

1999). Skuldaþingsey would then represent an early,

presumably 10th-century, stage where assemblies

were convened by relatively weak chieftains who

were aiming to establish regional authority over a

large group of more or less evenly influential local

leaders, while Þingey belongs to a later stage

when a good portion of the lesser fry among the

local leaders had been made politically irrelevant

and the remaining ones are increasingly grouped

together in factions, either behind one of the three

chieftains who in theory convened the spring assembly,

or in regional or other blocs, perhaps formed

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

122

to counteract the increasing power of the regional

chieftains. The third stage would then be represented

by one chieftain emerging as paramount over the

region, at which point he can be expected to abolish

the assembly, having established such a firm grip

over the region’s leaders that he no longer needed

to go through the motions of participatory decision

making. This last stage is what the paramount

chieftain of the neighboring region of Eyjafjörður

reached around 1190 (Sturlunga saga I:170), and

judging from the absence of spring assemblies from

descriptions of the political strife in the 13th century,

it seems that in this he was not alone.

Whether this reading is correct is another matter.

Only more comprehensive excavation of the assembly

sites can help settle that question.

Symbolism for its Own Sake

It is easy to read politics into the booths at the

Icelandic assembly sites (much easier than it is to

get it right!), but there is another dimension to this

building activity that cannot be ignored. This facet

relates not to the political syntax of the booths—how

they came to represent the political landscape of

their assembly regions—but to the resonance they

had as buildings on sites dominated by their natural

settings and as a rule peripheral to areas of dense

settlement. We cannot know what was going through

the minds of the people who built the first booth at an

assembly site, but the political syntax reconstructed

here cannot have been formed at that stage. Whatever

their aims, the reason this caught on and became

more or less obligatory at Icelandic assembly sites

must be that it appealed to people’s sensibilities in

some way. This appeal was likely many-layered,

but it can be suggested that it was about creating

permanent monuments in the landscape, monuments

signalling people’s commitment to the political and

judicial structures being created, but also in a more

general way symbolizing the new society and its

right to exist in a previously uninhabited country. It

seems that the colonists sought to put their mark on

the landscape in many different ways, including an

enormous effort in building earthworks (Einarsson

et al. 2002), but such symbols on sites of collective

decision making and dispute resolution would have

been particularly poignant. As material markers of

the assemblies’ function, and symbols of their legitimacy,

the booths can also be seen as substitutes

for whatever it was (groves, burial mounds, stone

settings, traditions) that hallowed assembly sites

in the homelands (see Sanmark and Semple 2008).

The monumentality of the booths would have different

connotations from the features at Scandinavian

assembly sites, but they would serve the same

purpose of marking the place, its uniqueness, and

significance, and they would, as time went by, come

to represent history and tradition. The fact that in

many cases the booths are still there suggests that,

irrespective of their functionality and actual use,

their monumentality left a lasting impression.

Conclusions

Assemblies with booths seem to be confined to

the colonies established in uninhabited lands in the

North Atlantic during the Viking Age and may even

be particular to Iceland. Although much remains to

be learned about these sites, not least their dating,

it is possible to hypothesize about the meaning of

the booths, what they represent, and how their sizes,

numbers, and distributions can support narratives

about political landscapes and political developments.

I have argued here that booths represent

neither chieftains nor individual farmers but rather

local communities of 5–15 farms, most no doubt

dominated by a local leader who would have been

the delegate at the assembly. More tentatively, it can

be suggested that the size range of the booths can

serve as an index of the homogeneity of the political

landscape, and that the arrangement and clustering

of the booths gives indications about how factionalized

the assembly was. None of this would have been

possible for us to wonder about if the colonists had

not felt a need to create material markers, symbols

of their commitment to the new institutions being

created, contributing to a sense of permanence, belonging,

and legitimization. The materiality of the

booths may only have provided the faintest echo of

the hallowedness of long-established assembly sites

in the homelands, but however faint, it would have

been an important echo in that it provided a sense of

rightness, a sense which would have been particularly

important in the process of building new judicial

and political institutions.

These hypotheses are necessarily speculative. I

hope, however, to have demonstrated the interpretational

potential of the Icelandic assembly sites—that

it is vast—and the need for large-scale and comprehensive

excavations to develop this potential into

real understanding of the political landscape of the

North Atlantic and its political developments in the

10th to 13th centuries.

Acknowledgments

The subject of this paper was originally presented

at the International workshop “Ancient Assemblies in

Europe: From Agora to Althing”, in Þingvellir, Iceland,

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

123

Friðriksson, A., H.M. Roberts, G. Guðmundsson, G.A.

Gísladóttir, M.Á. Sigurgeirsson, and B. Damiata.

2005. Þingvellir og þinghald að fornu. Framvinduskýrsla

2005. Fornleifastofnun Íslands, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 34 pp.

Friðriksson, A., E.Ó. Hreiðarsdóttir, H.M. Roberts, and

O. Aldred. 2007. Fornleifarannsóknir í S-Þingeyjarsýslu

2006. Samantekt um vettvangsrannsóknir í

Skuldaþingsey, Þegjandadal, á Litlu-Núpum, og Fljótsheiði.

Fornleifastofnun Íslands, Reykjavík, Iceland.

17 pp.

Halldórsson, Ó. (Ed.) 1987. Færeyinga saga. Stofnun

Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi (Rit 30). Reykjavík, Iceland.

142 pp.

Helle, K. 2001. Gulatinget og Gulatingslova. Skald, Leikanger,

Norway. 240 pp.

Íslenzk fornrit I. 1968. Íslendingabók. Landnámabók, J.

Benediktsson (Ed.). Hið íslenzka fornritafélag, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 525 pp.

Iversen, F. In press. Houses of representatives? Courtyard

sites north of the polar circle—Reflections of communal

organization from the Late Roman period through

the Viking Age. In J. Carroll, A. Reynolds, and B.

Yorke (Eds.). Power and Place in Later Roman and

Early Medieval Europe: Interdisciplinary Perspectives

on Governance and Civil Organization. Boydell and

Brewer, Woodbridge, UK.

Karlsson, G. 2000. Iceland’s 1100 Years. History of a

Marginal Society. Mál og menning, Reykjavík, Iceland.

418 pp.

Olsen, A.B. 2005. Et vikingtids tunanlegg på Hjelle i Stryn.

En konservativ institusjon i et konservativt samfunn.

Pp. 319–354, In K.A. Bergsvik and A. Engevik (Eds.).

Fra funn til samfunn. Jernalderstudier tilegnet Bergljot

Solberg på 70-årsdagen. Arkeologisk institutt, Universitetet

i Bergen, Bergen, Norway. 426 pp.

Ólafsson, G., and M. Snæsdóttir 1976. Rúst í Hegranesi.

Árbók hins íslenzka fornleifafélags 1975:69–78.

Onsøien Strøm, I. 2007. Tunanlegg i Midt-Norge. Med

særlig blikk på Væremsanlegget i Namdalen. Unpublished

hovedfagsopgave, Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige

universitet i Trondheim, Norway. 107 pp.

Ordbog over det norrøne prosasprog. A dictionary of

Old Norse prose. 1989–2004. 3 vols. Arnamagnæanske

kommission, Copenhagen, Denmark. Available

online at http://www.onp.hum.ku.dk/. Accessed 26

August 2013.

Pantos, A., and S. Semple (Eds.). 2004. Assembly Places

and Practices in Medieval Europe. Four Courts Press,

Dublin, Ireland. 251 pp.

Rafnsson, S. 1993. Páll Jónsson Skálholtsbiskup. Nokkrar

athuganir á sögu hans og kirkjustjórn. Ritsafn

Sagnfræðistofnunar 33, Reykjavík, Iceland. 139 pp.

Sanmark, A. 2010. The case of the Greenlandic assembly

sites. Journal of the North Atlantic 2009–2010 (Special

Volume 2):182–196.

Sanmark, A. 2013. Patterns of assembly: Norse thing

sites in Shetland. Journal of the North Atlantic Special

Volume 5:96–110.

7–8 September, 2008. I am grateful to Adolf Friðriksson

and Garðar Guðmundsson of the Icelandic assembly project

for permission to use their new plans of assembly sites

to illustrate this discussion. The paper has benefited from

the comments of Adolf Friðriksson, the editors, and two

anonymous reviewers.

Literature Cited

Barrett, J.H., and A. Slater. 2009. New excavations at

the Brough of Deerness: Power and religion in Viking

Age Scotland. Journal of the North Atlantic

2(1):81–94. Available online at doi: http://dx.doi.

org/10.3721/037.002.0108. Accessed 26 August 2013.

Bruun, D. 1928. Fortidsminder og Nutidshjem paa Island,

2nd Ed., Gyldendal, Copenhagen, Denmark. 416 pp.

Brøgger, A.W. 1937. Hvussu Føroyar vórðu bygdar.

Inngongd til løgtingssøgu Føroya. J. Patursson

(Transl.). Føroya løgting, Tórshavn, Faroes. 226 pp.

Christensen, A.E., Jr. 1974. Telt. Pp. 177–179, In O. Olsen

et al. (Eds.). Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk

middelader XVIII. Bókaverzlun Ísafoldar, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 724 pp.

Crawford, B.E. 1987. Scandinavian Scotland. (Scotland in

the Early Middle Ages 2), Leicester University Press,

Leicester, UK 274 pp.

Darvill, T. 2004. Tynwald Hill and the “things” of power.

Pp. 217–232, In A. Pantos and S. Semple (Eds.). Assembly

Places and Assembly Practices in Medieval

Europe. Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ireland. 251 pp.

Diplomatarium islandicum eða íslenzkt fornbréfasafn sem

hefir inni að halda bréf og gjörninga, dóma og máldaga

og aðrar skrár, er snerta Ísland eða íslenzka menn.

1853–1972. 16 vols. Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag,

Kaupmannahöfn/Reykjavík, Iceland.

Einarsson, Á., O. Hansson, and O. Vésteinsson. 2002. An

extensive system of medieval earthworks in Northeast

Iceland. Archaeologia Islandica 2:61–73.

Eithun, B., M. Rindal, and T. Ulset (Eds.). 1994. Den eldre

Gulatingslova. Norrøne tekster nr. 6. Riksarkivet,

Oslo, Norway. 208 pp.

Friðriksson, A.1994. Sagas and Popular Antiquarianism

in Icelandic Archaeology. Avebury, Aldershot, UK.

212 pp.

Friðriksson, A. 2002. Þinghald til forna.

Framvinduskýrsla 2002. Fornleifastofnun Íslands,

Reykjavík, Iceland. 54 pp.

Friðriksson, A. 2004. Þinghald að fornu. Fornleifarannsóknir

2003. Fornleifastofnun Íslands, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 57 pp.

Friðriksson, A. 2011. Þingstaðir. Pp. 344–357, In B.

Lárusdóttir. Mannvist. Sýnisbók íslenskra fornleifa.

Opna, Reykjavík, Iceland. 470 pp.

Friðriksson, A., and O.Vésteinsson. 1992. Dómhringa

saga. Grein um fornleifaskýringar. Saga 30:7–79.

Friðriksson, A., H.M. Roberts, and G. Guðmundsson.

2004. Þingstaðarannsóknir 2004. Fornleifastofnun

Íslands: Reykjavík, Iceland. 48 pp.

O. Vésteinsson

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

124

Þórðarson, M. 1945. Þingvöllur. Alþingisstaðurinn forni.

(Saga alþingis II). Alþingissögunefnd, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 287 pp.

Zoëga, G., and G. St. Sigurðarson. 2010. Skagfirska

kirkjurannsóknin. Árbók hins íslenzka fornleifafélags

2010:95–116.

Endnotes

1In this context. The low number of booths at Árnes, even

if it has been halved by erosion, undermines my hypothesis

(Vésteinsson 2009) that Árnes originally served the

whole of the southern plains. That hypothesis could only

work if the booths were built after the plains had been

split into two spring assembly areas.

2Counting parishes is easier than counting booths but it is

not unproblematic. These figures are based on Auðunarmáldagar

from 1318 for the northern diocese of Hólar

(Diplomatarium islandicum 2:423–489) and the list of

churches in the southern diocese of Skálholt attributed

to Bishop Páll Jónsson and originally compiled around

1200 (Rafnsson 1993, Vésteinsson 2012). It is assumed

that Skuldaþingsey and Þingey are not contemporary and

that they both served the same region. It is unclear how

large the areas were from which Leiðarnes and Leiðvöllur

were attended.

Sanmark, A., and S.J. Semple. 2008. Places of assembly.

New discoveries in Sweden and England. Fornvännen

103(4):245–259.

Sigurðsson, J.V. 1999. Chieftains and Power in the Icelandic

Commonwealth. Odense University Press, Odense,

Denmark. 255 pp.

Stigum, H. 1957. Bu (vn. Búð). Norge. Pp. 331–334, In

J. Brøndsted et al. (Eds.). Kulturhistorisk leksikon for

nordisk middelader II. Bókaverzlun Ísafoldar, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 688 pp.

Storli, I. 2010. Court sites of arctic Norway: Remains of

thing sites and representations of political consolidation

processes in the northern Germanic world during

the First Millennium AD? Norwegian Archaeological

Review 43(2):128–144.

Storm, G. (Ed.). 1888. Islandske annaler indtil 1578.

Norsk historisk Kildeskriftfond, Christiania, Norway.

Sturlunga saga I–II. 1946. J. Jóhannesson, M. Finnbogason,

and K. Eldjárn (Eds.). Sturlungaútgáfan, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 608 + 502 pp.

Unnarsson, B.Þ. 2006. Þingskálar á Rangárvöllum. Uppmæling

og samanburður við eldri rannsóknargögn

auk vangaveltna um tilgang og eðli staðarins. Unpublished

BA Thesis. University of Iceland, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 33 pp.

Vésteinsson, O. 2006a, Central areas in Iceland. Pp.

307–322, In J. Arneborg, and B. Grønnow (Eds.).

Dynamics of Northern Societies. Proceedings of the

SILA/NABO conference on Arctic and North Atlantic

Archaeology, Copenhagen, 10–14 May 2004. Publications

of the National Museum. Studies in archaeology

and history 10, Copenhagen, Denmark. 415 pp.

Vésteinsson, O. 2006b. Communities of dispersed settlements.

Social organization at the ground level in

tenth- to thirteenth-century Iceland. Pp. 87–113, In W.

Davies, G. Halsall, and A. Reynolds (Eds.). People and

Space in the Middle Ages, 300–1300. Studies in the

Early Middle Ages 15. Brepols, Turnhout, Belgium.

366 pp.

Vésteinsson, O. 2007. A divided society. Peasants and the

aristocracy in medieval Iceland. Viking and Medieval

Scandinavia 3:117–139.

Vésteinsson, O. 2009. Upphaf goðaveldis á Íslandi. Pp.

298–331, In G. Jónsson, H.S. Kjartansson, and V.

Ólason (Eds.). Heimtur—ritgerðir til heiðurs Gunnari

Karlssyni sjötugum, Mál og menning, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 415 pp.

Vésteinsson, O. 2012. Upphaf máldagabóka og stjórnsýslu

biskupa. Nýjar athuganir á kirknatali Páls biskups

Gripla 23:93–131.

Vésteinsson, O., Á. Einarsson, and M.Á. Sigurgeirsson

2004. A new assembly Site in Skuldaþingsey, NEIceland.

Pp. 171–179, In G. Guðmundsson (Ed.). Current

Issues in Nordic Archaeology. Proceedings of the

21st Conference of Nordic Archaeologists, September

6th–9th 2001, Akureyri, Reykjavík, Iceland. 214 pp.

Weinmann, C. 1994. Der Hausbau in Skandinavien vom

Neolithikum bis zum Mittelalter, mit einem Beitrag

zur interdisziplinären Sachkulturforschung für das

mittelalterliche Island. Quellen und Forschungen

zur Sprach- und Kulturgeschichte der germanischen

Völker, N.F. 106. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany.

477 pp.