[an error occurred while processing this directive]

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

5

Past Perspectives on the Thing

The word þing, i.e., thing, exists in all of the

Germanic languages and has been understood as “a

gathering in a certain place, at a certain time”. This

word is likely connected to the gothic þeihs, which

means time, and the older verbal theme to constrict

(Bjorvand and Lindeman 2007:1151–1152). In this

sense, the word possesses both spatial and temporal

dimensions. Discussion on the thing in European

research has for many decades hinged on the work

of Cornelius Tacitus, De origine, situ moribusa ac

populis Germanorum, also known as Germania,

written in A.D. 98. Tacitus’ description of the thing

(concilium) has led to extensive debate on whether

the medieval judicial and administrative topography

wholly or in part relates to late prehistoric

systems of organization and governance. Germania

has greatly influenced academic and non-academic

interpretations of the thing (Birley 1999:38). A

mid-9th-century manuscript of Germania, the Codex

Hersfeldensis, was rediscovered in a convent in Bad

Hersfeld in Germany in 1455 and quickly became

popular amongst influential German renaissance humanists,

including Conrad Celtes (†1508), Johannes

Aventinus (†1534) and Ulrich von Hutten (†1523).

Germania comprises approximately only 5500

words and 46 sections.

However, the secondary literature regarding this

work, including translations, is comprehensive. During

the 1800s, in the scientific and popular literature,

the idea of the Germanic thing merged with romantic

notions of an idealized complex of freedom-loving,

noble and proud Germanic peoples (Lenzing 2005,

Schank 2000, Semple 2011). These noble peoples

were envisaged to form a society situated somewhere

between the civilized Roman high society of

the south and the savage peoples of the far north.

The concept of the thing has been primary to these

discussions, fuelling perceptions of noble savagery:

primitive, spear-wielding tribes who placed a strong

emphasis on public debate and discussion at a designated

outdoor place of assembly. As part of this

emerging genre of highly nationalistic scholarship,

the identification of and debate on the existence and

purpose of the Gau emerged. The Latin term pagus

was used by Tacitus when documenting the existence

of the judicial system, and this was interpreted

as evidence of the early existence of the Gau.

Reliance on Tacitus and his accounts of the

Germanic groups north of the Roman frontier together

with Gau research fell into serious mistrust

after World War II. In the first half of the 1900s,

the Gau had been regarded as a proto-Germanic

thing area, and the term was adopted in nationalistic

discourses under the Third Reich, together

with the thing (Ding). Germany’s newly acquired

territories in the east were organized into so-called

Reichsgaue. Indeed, the administrative regions

of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei

(NSDAP) were termed Gau, and during the

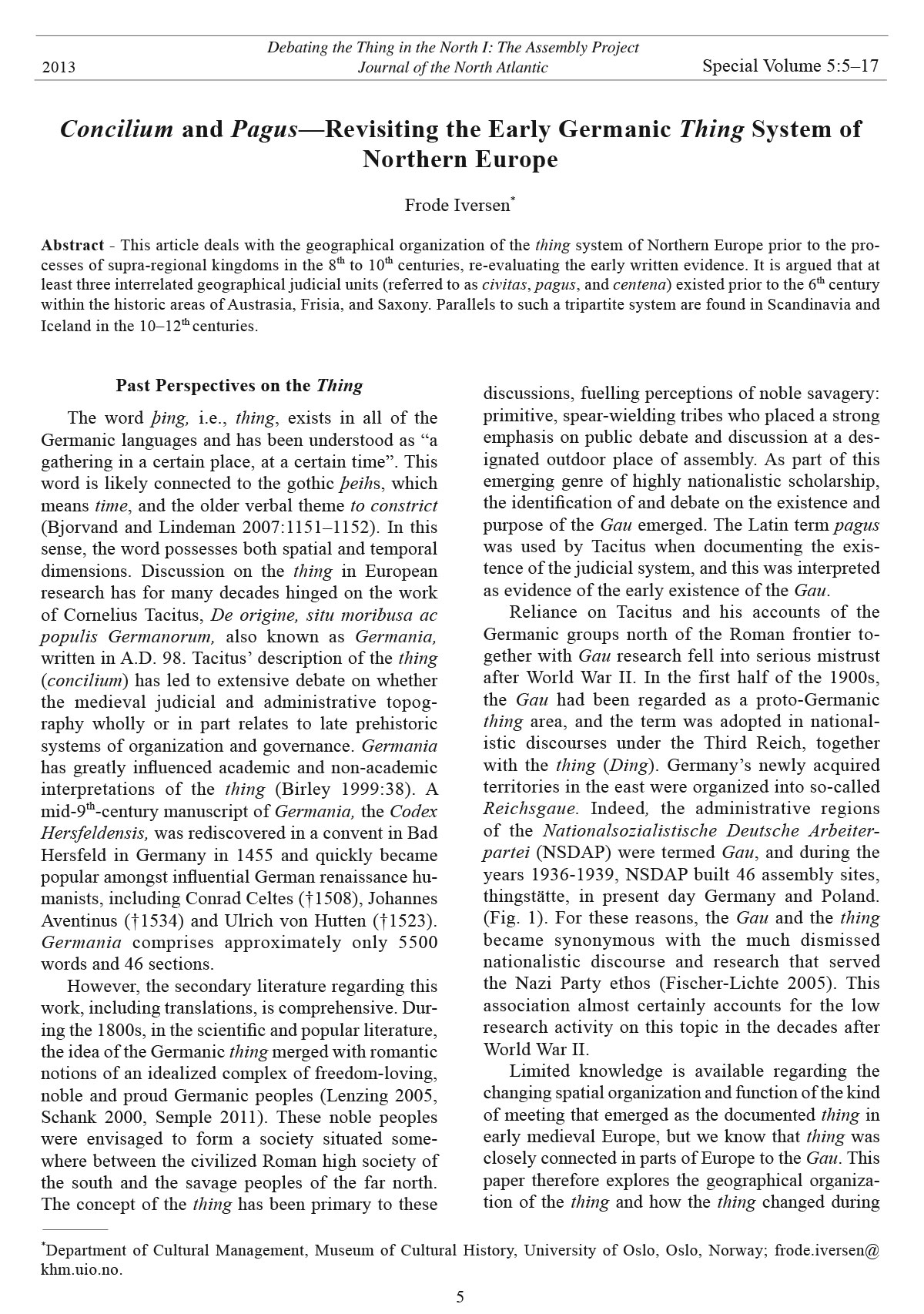

years 1936-1939, NSDAP built 46 assembly sites,

thingstätte, in present day Germany and Poland.

(Fig. 1). For these reasons, the Gau and the thing

became synonymous with the much dismissed

nationalistic discourse and research that served

the Nazi Party ethos (Fischer-Lichte 2005). This

association almost certainly accounts for the low

research activity on this topic in the decades after

World War II.

Limited knowledge is available regarding the

changing spatial organization and function of the kind

of meeting that emerged as the documented thing in

early medieval Europe, but we know that thing was

closely connected in parts of Europe to the Gau. This

paper therefore explores the geographical organization

of the thing and how the thing changed during

Concilium and Pagus—Revisiting the Early Germanic Thing System of

Northern Europe

Frode Iversen*

Abstract - This article deals with the geographical organization of the thing system of Northern Europe prior to the processes

of supra-regional kingdoms in the 8th to 10th centuries, re-evaluating the early written evidence. It is argued that at

least three interrelated geographical judicial units (referred to as civitas, pagus, and centena) existed prior to the 6th century

within the historic areas of Austrasia, Frisia, and Saxony. Parallels to such a tripartite system are found in Scandinavia and

Iceland in the 10–12th centuries.

Debating the Thing in the North I: The Assembly Project

Journal of the North Atlantic

*Department of Cultural Management, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; frode.iversen@

khm.uio.no.

2013 Special Volume 5:5–17

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

6

the formative process of supra-regional kingdoms in

the Middle Ages in northern Europe. I propose that

a re-evaluation of the few available sources used to

underpin Gau research is long overdue. Drawing on

research conducted through The Assembly Project,

the modi operandi and geographical organization of

the judicial and legislative assembly in the Nordic

regions is reconsidered in a long-term perspective.

New perspectives on the transformation of a communal

system into a royally managed power network are

proposed.

Key Questions and Perspectives:

From Communal to Royal Administrative

Landscapes

Clearly, it is difficult to describe or indeed find

a unified development of the thing for the whole of

Northern Europe. The development of such institutions

is complex and specific (Pantos and Semple

2004, Semple and Sanmark 2013). The level of royal

power, and hence the kings’ potential impact on the

communal thing system, varied greatly from the

core areas of the Frankish realm to the peripheries

of Scandinavia and beyond (Iversen 2011).

Previous research based itself on some general

principles and models that are worth revisiting.

First, the thing has been perceived as communal in

origin, in that power was enforced through “popular

assemblies” and “folk moots”. Communalism

has been defined as institutionalized interaction

in local societies solving public affairs (Imsen

1990:9). Second, the thing has not been regarded

as a static institution but rather something that

evolved gradually into a royal tool during the

Middle Ages (Barnwell 2003:2; Pantos and Semple

2004; Sanmark 2006, 2009; Wenskus 1984). The

terms Genossenschaft (cooperative) and Herrschaft

(lordship) are associated with the legal historian

Otto von Gierke (†1921) and the sociologist Maximilian

Karl Emil Weber (†1920) and have been

central to the discussion of the thing institution.

Within the perspective of historical materialism,

which focuses on class struggle, popular assemblies

Figure 1. The St. Annaberg assembly site, Góra Świętej Anny, Poland, was one of 46 Thingstätten built during the 1930s

by the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP). It had a capacity up to 30,000 people. Image © Sarah

Semple.

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

7

have been seen as a counterweight to the force of

lordship. Consequently, the power of the thing is

regarded as a mirrored reflection of the power of

the state (Imsen 1990:11): the stronger the state is,

the weaker the communal institutions are.

In this line of discussion, the German historian

Reinhard Wenskus (1984:445) claims that the

development of a stronger central administration

(Zentralgewalt) led to the loss of political power for

the thing (Volksversammlung). Describing the geographical

aspects of these developments, Niemeyer

(1968) introduced the analytical terms Urgau and

Großgau, framing the transition of older communal

pagi towards the larger, royally controlled comitati

(counties). A similar, but even more complex model

was put forth by the German law historian Karl von

Amira (1913:116–117) in his book Grundriss des

Germanischen Rechts (Fig. 2). This author suggested

that an extensive territorial reorganization

had taken place as a result of a change in power relations

and the processes of feudalism in the Frankish

Empire. According to him, aristocratic privileges of

immunity already transpired during the 6th century

(Amira 1913:158).

Somewhat simply, he argued for a tripartite

division of the thing system having occurred prior

to this reorganization; the area of the civitas (1),

which later comprised both an urban center and a

dependent rural territory, and earlier may or may

not have consisted of the tribal area (2), was divided

into medium-sized districts called Mittelbezirk (3),

each comprising several local thing areas. von Amira

(1913:116–119) saw the ON þriðjungr (third) and

fjórðungr (quarter) in Scandinavia, the thriðing in

Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, the leð (lathe) in Kent

and the rape in Sussex (which were recorded in the

10–12th centuries) as reminiscences of this organization

at an intermediate level. The idea was that toplevel

and medium-sized districts lost their significance

under Frankish-Carolingian rule because of an

advancing royal aristocracy in alliance with the king

(von Amira 1913:156). With immunity, manorial

judicial authority followed; such rights gradually

became territorialized, and new territories were created.

These areas were later recognized as comitati

(counties). The judicial system became divided into

Figure 2. According to Karl von Amira, a three-level communal system based on civitas / fylki → pagus / þriðjungr or

fjórðungr (= mid-level) → centena / hundred or herað (local thing) was transformed to a system based on larger units,

comitati (counties), in which the high court was controlled by the centenarius (count) and the lower courts were connected

to different familiae (Villikationen / Grundherrschaften). This is illustrated here by a model produced by the author.

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

8

a higher and a lower court, where the lower court

was linked with manorial rights and the higher court

was linked with the feudal lord or king (Lehnsherr)

(cf. Hensch and Michl, in press).

The formative processes of the Carolingian

counties have been much discussed. Heinrich

Dannenbauer (1956 [1941]) has reviewed the

conditions in Alamannia and Saxony, and Walter

Schlesinger (1969 [1941]) has studied Thuringia.

Hesse has been examined by Karl Kroeschell

(1956), and Swabia and Franconia have been studied

by Gertrud Kiefer (1954). Recently, the linguist

Roland W.L. Puhl (1999) examined the Saar-Mosel

district between the rivers Maas and Rhine, which

was a Frankish core area even before A.D. 481 (the

southern part of Austrasia). The research conducted

by these scholars does, to a certain extent, support

Amira’s hypothesis but is far more precise and is

based on stronger empirical grounds, dating the

process more definitively to the 9th century.

In particular, Puhl’s research is enlightening and

has a well-sourced base. Puhl’s research involves the

three medieval dioceses of Trier, Metz, and Verdun.

Around A.D. 600, Metz (AD 610), Trier (AD 575),

and Verdun (AD 634) were referred to as territorium.

These territories are named after centers called

civitates, and it is possible that these territories were

regarded as independent jurisdictions. Most likely,

Trier and Metz represented a core area in a dukedom

(ducatus) named Moselgau no later than A.D. 782

(Puhl 1999:180–182), and these territories contained

9–10 pagi each; in contrast, Verdun comprised only

one pagus.

In the years following A.D. 783, the term comitatus

appears. Puhl’s study shows that there were

fewer counties (comitati) than pagi. Only sixteen

or seventeen of the twenty-six units in question are

termed comitatus, and these clearly encompassed

several of the earlier pagi. The development was

complex and diverse; some pagi remained as independent

jurisdictions, even those that remained part

of a larger county (e.g., Rosselgau).

Puhl also argues that the development of the

comitatus was related to specific political processes,

and not least, to the division of the kingdom of Lothar

II in A.D. 870 (cf. Puhl 1999:528–530). Other

studies also show that direct continuity between the

older pagi and the later counties was rare and, as

Heinrich Mitteis (1975:151) summarizes, amalgamation,

partition, purchase, and subinfeudations had

in many cases led to such changes. It is clear that a

straightforward continuity model is utopian and that

convincing arguments for this can only be grasped

through more detailed studies, such as that of Puhl.

However, I perceive Amira’s model (Fig. 2) as relevant

for the understanding of the thing system that

preceded the feudalized system and the large-scale

political changes in northern Europe during the 9th

and 10th centuries.

Below, I shall review a selected group of the key

sources in detail, thereby providing a platform for

the further evaluation and development of models

relevant for the understanding of these older legal

systems and transitions among them.

The General Principles of the “Communal”

Thing

Tacitus (98) provides the most comprehensive

account of the prehistoric thing in Northern Europe.

Specific details of Tacitus’s text show that he must

have been well informed, although other passages

portray a more confused author (Birley 1999). In

general, Germania represents his subjective view

of foreign ethnic groups. However, in this context,

I have extracted relevant information regarding the

thing in an attempt to understand the essence of Tacitus’

ideas.

As a starting point, Tacitus offered insight into

the relationship between the thing and the king in the

areas between the rivers Rhine, Vistula, and Danube,

and the Baltic Sea (Fig. 3). Here, kings were accepted

based on birth, and military leaders were determined

based on suitability: Reges ex nobilitate, duces ex

virtute sumunt (ch. 7). It is interesting to note that the

fines imposed at the thing were supposedly divided

between the king or the thing/community (rex vel civitas)

and the aggrieved party (ch 12).

During these assemblies, principes were elected

to uphold law and order in the pagus and villages.

It is unclear whether these represented different administrative

units. The elected or chosen principes

had the authority to handle small matters, whereas

larger matters had to be dealt with by the thing (ch.

11).1 It has been debated what Tacitus means by the

term principes, although usually this is defined as a

chieftain. Most likely, the term refers to a specific

type of lord, who held legitimate right to sanction

the law (Schulze 2004:31). Supposedly, each of the

chieftains had (or were allowed to have up to?) one

hundred followers, fellows from the people (ch.

12).2 The chieftains also received financial support

from the other members of the civitas, in the form

of livestock or grain, which was given freely. Gifts

from outsiders and neighboring communities were

welcomed (ch. 15).

The thing gathered on certain days under a new

or a full moon, except in cases of urgency (ch. 11).

The latter instance called for extra-ordinary meetings.

When the participants found it appropriate,

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

9

they took to their seats armed (ch. 11).3 A priest imposed

silence and had the authority to inflict punishment

if this was not complied with. Following these

initial proceedings, the king or the principes put

forth their agenda. The congregation displayed their

disagreement by growling and their agreement by

joining spears (frameas) (ch. 11).4 The latter, known

as ON vápnatak Wapentake, even became the designation

of the local assembly units in the Norse colonization

areas in Northern Britain, the Danelaw, and

this was recorded from A.D. 962 onwards (Nielsen

1963:647).

Tacitus mentions a type of representational assembly/

cultic gathering used by the Semonerians

(ch. 39). These people formed a substantial tribe

that resided in the areas between the rivers Elbe and

Oder, considered themselves the main tribe of the

Suevi, and allegedly inhabited hundreds of pagi.

Delegates (legationes) from kindred groups of people

met at fixed times (statum tempus) by a sacred

grove. The Semonerians derived their origin from

the very same sacred place their ancestors had consecrated

and believed that everyone and everything

was subordinate to the supreme and all-ruling deity.

Supposedly, the meeting was initiated by the sacrifice

of a human. Tacitus mentions sacred groves

(lat. nemus, lūcis) (ch. 9, 10, 39, 40, and 43) several

times, meaning small groups of trees or open forested

areas with slight undergrowth (eng. grove).

Only in this instance, however, is it stated that the

grove itself was the actual meeting place (ch. 39).

To summarize, many recognizable elements are

part of the thing system that Tacitus describes. The

principles of both regular and extra-ordinary gatherings

are well known in Scandinavia and Frisia, as

clearly testified by the almost 1000-year-younger

sources. The fact that the parties could solve disputes

outside of these gatherings by prescribing and

receiving fines of damage is also well known. Tacitus

even mentions a variant of representational assemblies,

which is how both the regional law-things

and the medium-sized quarter things operated in

medieval Scandinavia, according to laws and postmedieval

accounts, such as the Thing-books.

Figure 3. Map of “Old Germania” (Germaniae veteris typus) by Wilhelm and Joan Blaeu (1645) in Theatrum Orbis Terrarum,

sive Atlas Novus. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

10

Rechtswörterbuch translates this as gebotenes

Gericht, meaning a “bidden” or “extra-ordinary” assembly.

5 Initial evidence of the bodthing dates from

A.D. 1108 (Waitz 1886:44). The term can be related

to the fact that messages were dispatched when announcing

meetings that would occur outside of the

regular times. Fimelthing has been interpreted as a

type of court of judgement or movable court (Rives

However, Tacitus appears to assume a strong

component of cultic elements in the top-level gatherings.

In general, the ordinary participants of the

thing were free warriors who had reached adulthood,

whereas dishonored people and thralls were

excluded. Freed thralls held an intermediate position

but were precluded from acquiring higher positions

in society. The spear (framea) was an important judicial

symbol and represented the will of the freemen

to defend the law and uphold order. Weapons were

carried during the assembly. Both legal and cultic

activities took place in the larger assemblies. Tacitus

remains vague regarding the spatial organization of

the assembly but appears to presuppose the existence

of administrative units at different levels, both

at the civitas and the pagus levels. It appears that

the early thing embedded several functions, which

were later conducted by different institutions, in

particular, the military and religious functions. We

must thus ask whether any other evidence exists that

supports the picture drawn by Tacitus regarding the

spatial organization of the thing.

The Earliest Evidence of the “Germanic” Thing

An inscription dated to the 3rd century, which was

found near Housesteads Roman Fort by Hadrian’s

Wall in Cumbria, UK, in 1883, gives important clues

to the early thing system. The inscription contains

the name Thincsus, “Thincso”, which is the oldest

indirect evidence of the word thing in Germanic

(Fig. 4; Wenskus 1984:443). The Latin inscription

reads, Deo Marti Thincso et duabus Alaisiagis Bede

et Fimmilene et n (uminibus) Aug (ustormum) Germ

(ani) cives Tuihanti v (otum) s (olvit) l (ibens) m (erito)

(Bosanquet 1922:187, Collingwood and Wright

1965:RIB 01593). This has been translated as: To

the god Mars Thincsus and the two Alaisagae, Beda

and Fimmilena, and the divine spirit of the emperor,

the German tribesmen from Tuihantis willingly and

deservedly fulfil their vow (Ireland 2009:184).

The main theory is that mercenaries/soldiers

from the current area of Twenthe in the eastern Netherlands

(Germani cives Tuihanti) raised the stone in

honor of the gods. Frisian ceramics have also been

found at the site, adding support to the theory (Rives

1999:160–161). Wilhelm Scherer is the first person

to have linked the names Beda and Fimmilena to the

bodthing and fimelthing, both of which were mentioned

in Frisian legal texts from A.D. 1100 onwards

(Richtoften 1840:391, Scherer 1884:574, Waitz

1886:44).

The Frisian bodthing signified an extra-ordinary

assembly (Wirada 1819:9). The Deutsches

Figure 4. This altar-shaped pillar was used as a door-jamb.

The inscription, which dates from the 3rd century, contains

the name “Thincso”, which is the oldest indirect evidence

of the word thing in Germanic. Photo after Budge

(1907:190).

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

11

military action. Furthermore, Caesar is the first to

have offered insight into geographical organization.

The civitas of the Celtic Helvetians appears to have

consisted of four pagi, of which Caesar names two:

pagus Tigurinus and pagus Verbigenus (Caesar

7.7.75; Puhl 1999:14).

Thus, a substantial geographical area was divided

into four smaller areas, of which the exact circumferences

are not known. It is uncertain whether

this reflects an early occurrence of the geographical

principle of quarter divisions, of which much later

examples are known from both Frisia and Scandinavia.

The degree of projection of Roman conditions

onto this source and its reliability are debateable

(c.f. Brunner 1887:116, note 13). However, Gregory

of Tours (538–594) also regarded the pagus as a

subdivision of the civitas, but held that the concepts

were also synonymous with subdivisions of dukedoms

(ducates) (Brunner 1887:14–15). According to

Isidore of Seville (ca. 560–636) in Etymologiae sive

origines, the pagus was identical to a conciliabula

(= thing area), which had fixed assembly sites (Puhl

1999:15). Isidore was especially referring to the

conditions in southern Europe, where undoubtedly

the pagi had jurisdictions with fixed assembly sites.

According to Puhl, the size of the pagus apparently

exceeded the size of local assemblies. Well over half

of the pagi examined by Puhl had diameters of approximately

40 to 60 km, whereas the diameters of

nine were less than 20 km (Puhl 1999:520).

The representational thing, Saxony

The famous biography Vita Lebuni antiqua,

which was written by a monk named Hucbald († ca.

930), mentions the Saxon thing held by Marklo at

the river Weser. Lebuin died around the year A.D.

775, and the narrative addresses events prior to the

Carolingian conquest of Saxony. The Saxons were

led to war by an (elected) duke (dux). Hucbald mentions

three legal and social categories regarding the

annual assembly: the nobles (adalinge, nobiles), the

free (frilingi, liberi, ingenuiles) and the liberated

(lassi, liberti, serviles). During the general assembly

(generale concilium), the leaders (satrapae) and

twelve men from each pagus met (Schulze 2004:31,

Waitz 1886:366–367). According to Hucbald, the

thing held authority regarding matters of war and,

especially, important litigations.7 It is debated

whether these twelve men could be recruited from

all of the above-mentioned groups or whether only

the nobles were eligible (cf. Landwehr 1982:117–

142). Regardless, this record illustrates the existence

of a collective representational assembly in Saxony

during the 700s. The word satrapae has also been

1999:161). The word fimel might be related to the

ON verb fimast, which translates “to hurry”. However,

the interpretation is uncertain and the evidence

meager.

Heinrich Brunner (1887:148) associated fimmelthing

with Afterding, assemblies that were held

after the regular one (cf. Nachgericht). The intention

may have been to make the decisions of the

larger assemblies widely known. Following these

assemblies, information was transferred into the local

communities, which had to be done quite hastily.

Scherer’s interpretation received some support from

the Austrian philologist Siegfried Gutenbrunner

(1936:24–40) and more support from the French

philologist Georges Dumézil (1973:82). Gutenbrunner

interpreted the names Thincsus, Beda and Fimmilena

as the names of one god and two goddesses,

who were protectors of the thing. The interpretation

is still relevant, but there could be a number of

reasons to be cautious (Rives 1999:161, Wenskus

1984). A significant gap in time occurs between the

3rd century and the Frisian legal text of the 12th and

13th centuries. In this instance, the three names of the

gods could bear witness to the existence of a system

of fixed assemblies (Thincsus), extra-ordinary assemblies

(Beda) and “information assemblies” (Fimmilena).

This interpretation indicates the presence of a

system of assemblies that was both fixed and flexible

in the Frisian area in the 3rd century. The need to hold

“information meetings” after ordinary gatherings

might indicate the existence of fixed regional representational

things. Such a system could agree well

with the judicial practice described by Tacitus, with

its fixed and extra-ordinary gatherings, as well as annual

representational assemblies/cultic gatherings.

Spatial Organization of the Thing

Julius Caesar was the first who mentioned the

thing in northern Europe in his Commentarii de

Bello Gallico around 50 B.C. The Romans erected

a bridge across the Rhine and threatened the Suebi

with an invasion, supposedly because of their attacks

on the new Roman province of Gaul. Caesar

explains that the Suebi called a thing (concilium)

in accordance with their tradition. The thing decided

that a large army was to be gathered and gave

orders to evacuate the villages.6 Thus, it had the

authority to make decisions on behalf of a larger

collective and, as such, held authority over an extensive

geographical area. The incident also specifically

reminds us that the thing was called during a

time of trouble and held the function of organizing

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

12

documented in Old Persian and Ancient Greek and

denotes the Protector of the Province, referring to a

form of sanctioning authority. The word was most

likely used by Hucbald in reference to a biblical

term.

The quarter thing and the land thing, Frisia

The Frisian thing system is also interesting in

this context because it provides further information

on the geographical organization of the two highest

levels. The lawyer and historian Tileman Dothias

Wiarda (1818:9–13) was one of the first people to

give a detailed description of this. Wiarda belonged

to the Romantic tradition but had particularly good

access to archives due to his position as the secretary

of the Ostfriesische Landschaft. More recently, the

historian Hajo von Lengen (2003) has conducted

research on this subject.

According to the Freeska Landriucht (Frisian

Landlaw), Frisia was divided into seven sealands

(Richthofen 1840: 110-112, Wiarda 1819:9, 18–

19). The exact division is not known for sure. In the

14th century, the area consisted of 23 separate provinces

(-land) (Lengen 2003). Collective assemblies

for Frisia were held at Upstalboom (“the uppercommon-

tree”) in Brokmerland, the first of which

was documented in A.D. 1216. This assembly gathered

annually on the third day after Easter and met

for the last time in A.D. 1327, when it relocated to

Groningen.

Several of the seven sealands were divided into

quarters in the late Middle Ages called fardingdela.

This division is documented for Brokmerland, which

comprised four such quarters, according to the

13th-century Brokmer law (Buma 1949). In addition,

both Rustringia and Hunsingo were supposedly split

into quarters. In Brokmerland, quarterly assemblies

were held at fixed times (Wirada 1818:13). According

to the Deutsches Rechtswörterbuch, these appear

and are referred to as liodthing from A.D. 1080 to

the 1800s.8 As previously mentioned, extra-ordinary

assemblies were referred to as bodthing. The delegates

to the main east Frisian assembly appear to

have been appointed at the regular quarter things.

The delegates were representatives of their district

or parish, of which the latter was termed karspel.

In addition, all of the delegates at the four quarter

things of Brokmerland gathered twice annually.

This gathering was called a “land thing” (lantding),

where disputes between the quarters were settled

and new laws were adopted.

The 1323 treaty of the Uppstallisbam states that

the seven sealands were subject to mutual military

obligations should any of the lands be attacked by

Saxons or Northmen (Henstra 2000:327, Richthofen

1840:102, Wiarda 1819:19). The lands had their own

laws and their own seal. In this sense, they functioned

as independent jurisdictions although they

were allied through having military responsibilities

towards one another.

The malloberg, thunginus, and centenanius, Lex

Salica

As previously mentioned, Tacitus differentiates

between the pagus-level and annual collective

assemblies or cult gatherings that took place at a

regional level. It is unclear whether the pagus was

subdivided into lesser jurisdictional areas at that

time. The Salician Law (Lex Salica) of the Frankish

area, one of the Germanic tribal laws, contains

the most tangible information regarding this point.

This law was compiled between A.D. 507 and 511,

presumably by order of King Clovis I, and the

earliest manuscripts date to the 8th century (Drew

1991:53). Clovis’ core area of power was Neustria

and Austrasia; he conquered the present-day area

of southern France (Aquitaine) and Swabia at the

beginning of the 6th century. Immediately following

these events, the need to develop a mutual law that

applied to the entire kingdom could have arisen,

acting as the catalyst for the development of the

Lex Salica (Eckhardt 1969, Kroeschell 1972, von

Amira 1913:23–24). This merging process is also

indicated in the short prologue (from A.D. ca. 700)

explaining the origin of the law, which names four

just men, who were chosen from many: Wisogast,

Arogast, Salegast, and Widogast (Kroeschell 1972,

Wood 1998:111). Allegedly, these men came from

Bothem, Salehem, and Widohem beyond the Rhine

and thus presumably were from the northeast part

of Austrasia (the later Francia). 9 Most likely, these

men were assembly leaders or acted as legal authorities

in the areas from which they came. Supposedly,

at three larger assemblies (mallos convenientes),

these men debated the sources of litigation and

gave judgement on each of these sources (Wormald

2003:28).

According to the Lex Salica, both thunginus

and centenanius held the right to convene an assembly

when a certain type of property transaction

was to take place (acfatmire) (Drew 1991:108,

110; Eckhardt 1969:44, 46). The centenani was associated

with the centena, which has traditionally

been recognized as a subordinate thing area of the

pagus (Drew 1991:229 note 26). Such transactions

followed specific procedures at certain correct assembly

sites, and the transaction was only legitimate

if it occurred at a malloberg in the presence of a

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

13

According to the Heerestheorie, the term hundred

indicates the number of men assembled for military

campaigning. Others have argued that the number is

not to be taken literally but instead indicates a hoard

of men (Haufentheorie). One final theory is that the

word denotes a hundred settlements (Hufentheorie)

(Andersson 2000:236–238). The German researcher

Heinrich Dannenbauer (1958) believed that the

Frankish centena was originally the jurisdiction of

the Königsfreie (liberi, ingenui, franci homines),

who were free individuals subject to military obligations.

Other scholars have viewed the centena

as meaning units subject to and led by a hunto in

order to strengthen Frankish influence (Hensch

2010:53–54, Kroeschell 1972:229). Apparently,

some Königsfreie, who were denoted as Bargilden,

Biergelden, or Barschalken, “survived” in Germany

as free peasants until the High Middle Ages when

they finally disappeared (Feed 1976:223–224).

Beyond the vague information provided by

Tacitus regarding this matter, the centena is only

initially supported, with any degree of certainty, in

two decrees by King Chlothar (AD 511–558) and

King Childebert (AD 596) (Murray 1988, Wormald

2003:39). Clearly, the centena played a role in the

judicial system. These units were held liable for

compensation if community members were subjected

to theft due to lack of security or caused by

conspiracy, or if a thief was not extradited to another

centena (Pactus pro tenore pacis 84; Eckhardt

1962:99–102). A person who refused a request by a

centenarius or any other judge to institute proceedings

against a criminal had to pay a fine of 60 solidi

(Decretio Childeberti 3:1, Eckhardt 1962:4–5). In

king (teoda) or a thing leader (thunginus) (Drew

1991:111).10

The malloberg, connected to OHG mahal (law

assembly), is not only mentioned in this law but is

also found in many place-names (Fig. 5; Hensch

2010:54–55; Hensch and Michl, in press). The use

of alliteration and the oral form (… teoda aut thunginum)

indicates an old age of this specific passage. The

American historian and linguist Leo Wiener (1915)

discussed the meaning of thuniginus more thoroughly

and concluded the word referred to a dignified, elderly

warrior of high standing. The term thuniginus fell

out of use in the Frankish era, when it was replaced

by count (as judge; Wiener 1915:26, 35–36). A likely

interpretation is that the thunginus functioned as a

leader of the pagus, or a larger unit, whereas the cenetarius

was the leader of the local assembly, which still

held the right to convene regional assemblies to adjudicate

property transactions.

Somewhat simply, I interpret this as evidence

for the early existence of a tripartite thing system

in the Frankish core area: law speakers (men like

Wisogast, Arogast, Salegast, and Widogast) were

present in larger areas, and the thunginus acted as a

mid-level thing leader, whereas the cenetarius—the

Germanic hunto—led local things.

The hundreds

Much is unclear about the hundred in the research

literature. The origin of the word centena is

not entirely clear. Cent means one hundred, and evidence

shows that centena was perceived as synonymous

with hundred in A.D. 1070 (centuni = hunnenduom)

(Gawlik 1978:1028, Kroeschell 2000:239).

Figure 5. A view from the top of Mahlberg, Frechetsfeld, close to Nuremberg, Bavaria, Germany. The prefix mahl derives

from OHG mahal, meaning assembly site. The site is located in the middle of the manorial complex of Lauterhofen, a royal

villa prior to A.D. 788. Photograph © Mathias Hensch.

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

14

Final Remarks

The transformation from petty to supra-regional

kingdoms in northern Europe between the 8th and

the 14th centuries has previously been viewed as a

teleological process that resulted in “nature-given”

national states (Bagge 2003). It is now clear that

“state formation”, or the development of supraregional

kingdoms, was a complex process in which

assembly sites and units must have played a crucial

part. The written sources reviewed here suggest the

possibility of a tripartite early thing system existing

in Austrasia and further north, including the Scandinavian

countries. The thing changed as a result

of stronger royal force and the growth of counties.

Most likely, the assemblies held at both the top and

medium levels were representational things, while

the exact character of the local assembly was vaguer.

Even if the sources are somewhat confused and difficult

to interpret, the many and strong similarities

among sources from Tacitus to the Scandinavian

provincial laws are striking.

This system may not have emerged in every part

of northern Europe, and it was certainly subject to regional

variability and change over time. A challenge

remains to find out why such a conservative system

changed at different times in different regions. There

is a need for a better understanding of which functions

were held by different things concerning crime,

land ownership transfer, law making, military matters,

and cult practices. In-depth studies of the sites

involved are essential, in addition to examining who

controlled these sites. Will it be possible to maintain

the traditional distinction between a “communal” and

a “royal” assembly system or is the boundary between

these more blurred than previously thought? Changes

in the spatial organization of assembly sites hold the

key to such questions and ares, as such, fundamental

for understanding the assembly system in northern

Europe from a long-term perspective.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Alexandra Sanmark (University of the

Highlands and Islands), Dr. Sarah Semple (Durham University),

Dr. Natascha Mehler (Vienna University), and Dr.

Mathias Hensch (Eschenfelden) for discussions, critical

reading, and comments with regards to this manuscript. A

special thank to Dr. Semple for discussions of the NSDAP

thingstätte at the Rewley House conference, Oxford, 2011.

Thanks to Jessica McGraw for translation and proofreading.

Literature Cited

Andersson, T. 1982. Hund, hundare och härad från

språklig synpunkt. Bebyggelsehistorisk Tidskrift

4:52–65.

this way, a centenarius functioned as an assembly

leader/judge in a centena.

The Swedish place-name scholar Thorsten

Andersson (1982, 2000) has shown that the Hundertschaft

existed outside, and in the periphery of,

the Carolingian kingdom. This author finds linguistic

evidence for this in four areas: Uppland and

Gotland in modern Sweden, Frisia, and Alamannia.

The earliest toponymic evidence occurred in Alamannia

in A.D. 776 (in Hattenhuntare), and there are

eight occurrences before A.D. 1007. Seven names

are known in the German Federal State of Baden-

Württemberg and one in present-day Switzerland by

the Bodensee. Four of these are also mentioned as

pagi, confusing the picture.

There are two certain cases of hundreds in Frisia,

but the system is best known from Uppland in Sweden,

where this (hundari) was the local thing area

(Andersson 2000:233–238). Three larger

jurisdictions were subdivided: Tiundaland (“land

with ten hundreds”), Attundaland (“land with eight

hundreds”), and Fjärdrundaland (“land with four

hundreds”). Collectively, these jurisdictions accounted

for one main thing district, in addition to

Västmanland, Södermanland, and Roden (Sjáland).

Several of these provinces had their own law, and

when not in compliance, the law of Uppsala had the

highest authority. The lǫ gmaðr of Tiundaland was

the leading law speaker, and the main thing was located

at Uppsala in Tiundaland, according to Snorri

Sturlusson (The saga of Olaf the Holy ch. 77; Holtsmark

and Seip 1979:227). The initial versions of the

names af Tindæ landi and Fiærðundæ landi were

documented during the 1300s, in conjunction with

events that had taken place in the mid-11th century.

However, the earliest certain account is the Florence

document from A.D. 1120, which includes the variants

Tindia, Fedundria, and Atanth (Lundberg

1982:402).

These arithmetic names are unique in the European

context and indicate planned territories, likely

comparable to counties and sýslur in Norway and

Denmark. In Norway, the term sýsla appears in the

early 11th century (Iversen 2008:18–19). England

was likewise organized in hundreds, as systematically

recorded in the Domesday Book from A.D.

1066. In this case, hundreds were subdivisions of

shires, which in many cases were identical with

counties. However, some Anglo-Saxon kingdoms

only consisted of one shire (Sussex and Kent) but

were subdivided in rapes and lathes, which may or

may not indicate the existence of different levels

in the thing system (Baker and Brookes 2013 [this

volume], Brookes and Harrington 2010).

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

15

Andersson, T. 2000. Hundare. Pp. 233–238, In R. Müller

(Ed.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde

15. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany.

Bagge, S. 2003. Fra knyttneve til scepter: Makt i middelalderens

Norge. Makt- og demokratiutredningen

1998–2003, no. 67. Oslo, Norway. 106 pp.

Baker, J., and S. Brookes. 2013. Governance at the Anglo-

Scandinavian interface: Hundredal organization

in the southern Danelaw. Journal of the North Atlantic

Special Volume 5:76–95.

Barnwell, P. 2003. Political assemblies: Introduction. Pp.

1–10, In P.S. Barnwell and M. Mostert (Eds.). Political

Assemblies in the Earlier Middle Ages Studies in

the Early Middle Ages 7. Brepols, Turnhout, Belgium.

Birley, A.R. 1999. Introduction. Pp. 11–40, In A.R. Birley

(Ed.). Tacitus, Agricola, and Germany. Oxford University

Press, Oxford, UK.

Bjorvand, H., and F.O. Lindeman. 2007. Våre arveord:

Etymologisk ordbok. Instituttet for sammenlignende

kulturforskning, Serie B, Skrifter 105. Novus, Oslo,

Norway. 1430 pp.

Blaeu, W., and J. Blaeu. 1645. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum,

sive Atlas. Novus, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Bosanquet, R.C. 1922. On an altar dedicated to the Alaisiagae.

Archaeologica Aeliana 19(3):185–97.

Brookes, S.J., and S. Harrington. 2010. The Kingdom and

People of Kent AD 400–1066: Their History and Archaeology.

The History Press, Woodslane, Australia.

160 pp.

Brunner, H. 1887. Deutsche Rechtsgeschichte. Systematisches

Handbuch Der Deutschen Rechtswissenschaft,

1. Duncker and Humblot, Leipzig, Germany. 629 pp.

Budge, W.E.A. 1907. An Account of the Roman Antiquities

Preserved in the Museum at Chesters, Northumberland.

Gilbert and Rivington, London, UK. 432 pp.

Buma, W.J. (Ed.). 1949. Die Brokmer Rechtshandschriften.

Oudfriese taal- en rechtsbronnen 5. Haag, Nijhoff,

and Gravenhage, Zaltbommel, The Netherlands. 307

pp.

Caesar, J.G. (F. Kraner and W. Dittenberger [Eds.]).1913–

1920. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, I–8. Weidmannsche,

Berlin, Germany.

Collingwood, R.G., and R.P. Wright. 1965. The Roman

Inscriptions of Britain (RIB). Inscriptions on Stone 1.

Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK. 790 pp.

Dannenbauer, H. 1956 (1941). Adel, Burg, und Herrschaft

bei den Germanen. Grundlagen der deutschen

Verfassungstentwicklung. Pp. 66–134, In H. Kämpf

(Ed.). Herrschaft und Staat im Mittelalter. H. Gentner,

Darmstadt, Germany.

Dannenbauer, H. 1958. Hundertschaft, centena, und huntari.

Pp. 179–239, In Grundlagen der Mittelalterlichen

Welt. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Germany.

Drew, K.F. 1991. The Laws of the Salian Franks (translated

and with an introduction by K.F. Drew). University

of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, USA. 272 pp.

Dumézil, G. 1973. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. University

of California Press, Berkeley, CA, USA. 157

pp.

Eckhardt, K.A. 1962. Pactus legis Salicae. Leges nationum

Germanicarum 4:1. Impensis bibliopolii Hahniani

Monumenta, Hannover, Germany. 327 pp.

Eckhardt, K.A. 1969. Lex Salica. Leges nationum Germanicarum

4:2. Impensis bibliopolii Hahniani Monument,

Hannover, Germany. 264 pp.

Feed, J.B. 1976. The origins of the European nobility: The

problem of the ministerials. Viator 7:211–242..

Fischer-Lichte, E. 2005. Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual: Exploring

Forms of Political Theatre. Routledge, London,

UK. 290 pp.

Gawlik, A. 1978 (Ed.). Die Urkunden Heinrichs IV., Teil

3. In Diplomata Regum et Imperatorum Germaniae

6(3):687–1107. Hansche Buchhandlung, Hannover,

Germany.

Gutenbrunner, S. 1936. Die germanischen Götter-namen

der antiken Inschriften. M. Niemeyer, Halle, Germany.

260 pp.

Hensch, M. 2011. Landschaft, Herrschaft, Siedlung—Aspekte

zur frühmittelalterlichen Siedlungsgenese im

Raum um die villa Lauterhofen, die civitas Amardela

und die urbs Sulzbach in der Oberpfalz (Bayern).

Beiträge zur Mittelalterarchäologie in Österreich

26:33–78.

Hensch, M., and E. Michl. In press. Der locus Lindinlog

bei Thietmar von Merseburg—Ein archäologischhistorischer

Beitrag zur politischen Raumgliederung

in Nordbayern während karolingisch-ottonischer Zeit.

In Jahrbuch für fränkische Landesforschung 72. Erlangen,

Germany.

Henstra, D.J. 2000. The evolution of the money standard

in medieval Frisia: A treatise on the history of the

systems of money of account in the former Frisia (c.

600–c. 1500). University of Croningen, the Netherlands.

426 pp.

Holtsmark, A., and D.A. Seip. 1979. Kongesagaer / Snorre

Sturluson. Norges kongesagaer 1–2. Gyldensdal, Oslo,

Norway. 343 pp.

Hucbaldus. 1934. Vita Lebuini antiqua. Pp. 789–795, In

A. Hofmeister (Ed.). Monumenta Germaniae Historica

30.2. Hahn, Hannoverae, Germany.

Imsen, S. 1990. Norsk bondekommunalisme: Fra Magnus

Lagabøte til Kristian Kvart, 1. Tapir, Trondheim, Norway.

226 pp.

Ireland, S. 2009. Roman Britain: A Sourcebook. Routledge,

London, UK. 284 pp.

Iversen, F. 2008. Eiendom, makt og statsdannelse:

Kongsgårder og gods i Hordaland i yngre jernalder og

middelalder. UBAS, Nordisk, 6. University of Bergen,

Bergen, Norway. 416 pp.

Iversen, F. 2011. The beauty of Bona Regalia and the

growth of supra-regional powers in Scandinavia. Pp.

225–244, In S. Sigmundsson (Ed.). Viking Settlements

and Viking Society: Papers from the Proceedings of

the Sixteenth Viking Congress, Reykjavík and Reykholt,

16–23 August 2009. University of Iceland Press,

Reykjavik, Iceland.

Kiefer, G. 1954. Grafschaften des Königs in Schwaben

und Franken. University Dissertation. Tübingen, Germany.

686 pp.

Kroeschell, K. 1956. Die Zentgerichte in Hessen und die

fränkische Centene. Pp. 300–360, In Zeitschrift der

Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte. Germanistische

Abteilung 73, Böhlau, Germany.

Kroeschell, K. 1972. Deutsche Rechtsgeschichte, 1. Westdeutscher

Verlag, München, Germany. 345 pp.

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

16

Kroeschell, K. 2000. Hundertschaft. Pp. 238–241, In R.

Müller (Ed.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde

15. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany.

Landwehr, G. (Ed.). 1982. Studien zu den germanischen

Volksrechten: Gedächtnisschrift für Wilhelm Ebel:

Vorträge gehalten auf dem Fest-Symposion anlässlich

des 70. Geburtstages am 16. Juni 1978 in Göttingen.

Rechtshistorische Reihe 1. Peter Lang Publishing,

Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany. 217 pp.

Lengen, H. 2003. Die Friesische Freiheit des Mittelalters—

Leben und Legende. Ostfriesische Landschaftliche

Verlag und Vertriebsges, Aurich, Germany. 512

pp.

Lenzing, A. 2005. Gerichtslinden und Thingplätze in

Deutschland. Langewiesche, Königstein im Taunus,

Germany. 192 pp.

Lundberg, B. 1982. Tiundaland. In Kulturhistorisk leksikon

for nordisk middelalder—fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid

18:402–404. Gyldendal, Oslo, Norway.

Mitteis, H. 1975. The State in The Middle Ages: A Comparative

Constitutional History of Feudal Europe.

North-Holland Medieval translations 1. North Holland

Publishing Co., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 419 pp.

Nielsen, H. 1963. Kolonisation. In Kulturhistorisk leksikon

for nordisk middelalder—fra vikingtid til reformasjonstid

8:644–650. Gyldendal, Oslo, Norway.

Niemeyer, W. 1968. Der Pagus des frühen Mittelalters in

Hessen. N.G. Elwert, Marburg, Germany. 259 pp.

Murray, A.C. 1988. From Roman to Frankish Gaul: “Centenarii”

and “Centenae” in the Administration of the

Merovingian Kingdom. Traditio 44:59–100.

Pantos, A., and S.J. Semple. 2004 (Eds.). Assembly Places

and Practices in Medieval Europe. Four Courts Press,

Dublin, Ireland. 251 pp.

Puhl, R.W. 1999. Die Gaue und Grafschaften des frühen

Mittelalters im Saar-Mosel-Raum. Saarländische

Druckerei und Verlag, Saarbrücken, Germany. 628 pp.

Richthofen, K. 1840. Friesische Rechtsquellen (reprint

1960). Scientia, Aalen, Germany. 582 pp.

Rives, J.B. 1999. Germania / Tacitus [translated with introduction

and commentary by J.B. Rives]. Clarendon

Ancient History Series. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK.

346 pp.

Sanmark, A. 2006. The Communal Nature of the Judicial

System in Early Medieval Norway, Collegium Medievale

19:31–64.

Sanmark, A. 2009. Thing organization and state formation.

A case study of thing sites in Viking and Medieval

Södermanland, Sweden. Medieval Archaeology

53:205–41.

Schank, G. 2000. “Rasse” und “Züchtung” bei Nietzsche.

Monographien und Texte zur Nietzsche-Forschung 44,

Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Gemany. 480 pp.

Scherer, W. 1884. Mars thingsus. Sitzungsberichte der

Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften

zu Berlin 25:571–582.

Schlesinger, W. 1969 (1941). Die Entstehung der Landesherrschaft.

Untersuchungen vorwiegend nach

mitteldeutschen Quellen. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft,

Darmstadt, Germany. 265 pp.

Schulze, H.K. 2004. Stammesverband, Gefolgschaft,

Lehnswesen, Grundherrschaft. Grundstrukturen der

Verfassung im Mittelalter 1 (Third Edition). W. Kohlhammer,

Stuttgart, Germany. 166 pp.

Semple, S.J. 2004. Locations of Assembly in Early

Anglo-Saxon England. Pp. 135–154, In A. Pantos and

S.J. Semple (Eds.). Assembly Places and Practices in

Medieval Europe, Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ireland.

Semple, S. 2011. Power of place: Assembly in the past

and present. Unpublished paper presented at the Rewley

House conference, Oxford: Anglo-Saxon Places

of Power, Governance, and Authority. Available from

the author.

Semple, S., and A. Sanmark. 2013. Assembly in North

West Europe: Collective Concerns for Early Societies?

European Journal of Archaeology 16(3):518–542.

Tacitus, C. 98. Agricola; Germania: Lateinisch und

deutsch. Latin text translated to german by Alfons Städele

(ed). Sammlung Tusculum, 1991. Wissenschaftliche

Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, Germany. 418 pp.

von Amira, K. 1913. Grundriss des Germanischen Rechts.

Grundriss der Germanischen Philologie 5. K.J. Trubner,

Straßburg, Germany. 302 pp.

Waitz, G. 1886. Urkunden zur deutschen Verfassungsgeschichte

im 10, 11, und 12. Jahrhundert (Second

Edition, 1886), I. Weidmann, Berlin, Germany. 80 pp.

Wenskus, R. 1984. Ding. Pp. 443–446, In H. Beck et al.

(Eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde,

Zweite, völlig neu bearbeitete und stark erweiterte

Auflage unter Mitwirkung zahlreicher Fachgelehrter,

vol. 5. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin, Germany.

Wiarda, T.D. 1819. Ancient laws and constitution of the

Frisons. The Edinburgh Review July, 1819:1–27.

Width, T. 1997. Agricola og Germania, til norsk ved

Trygve Width. Aschehoug, Fondet for Thorleif Dahls

kulturbibliotek and Det norske akademi for sprog og

litteratur, Oslo, Norway. 117 pp.

Wiener, L. 1915. Commentary to the Germanic Laws and

Mediaeval Documents. Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA, USA. 224 pp.

Wood, I. 1998. Franks and Alamanni in the Merovingian

Period: An Ethnographic Perspective. Studies in Historical

Archaeoethnology 3. Boydell, Woodbridge,

UK. 481 pp.

Wormald, P. 2003. The leges barbaroum. Pp. 21–53, In

H-W Goetz, J. Jarnut, and W. Pohl (Eds.). Regna and

Gentes: The Relationship between Late Antique and

Early Medieval Peoples and Kingdoms in the Transformation

of the Roman World. Brill, Leiden, The

Netherlands.

Endnotes

1De minoribus rebus principes consultant; de majoribus

omnes: ita tamen, ut ea quoque, quorum penes

plebem arbitrium est, apud principes pertractentur

(ch. 11).

F. Iversen

2013 Journal of the North Atlantic Special Volume 5

17

2Eliguntur in iisdem conciliis et principes, qui jura

per pagos vicosque reddunt. Centeni singulis ex

plebe comites, consilium simul et auctoritas, adsunt

(ch. 12). Tacitus is cryptic when he refers to pagi,

with a mobilization of one hundred foot soldiers

(ch. 6). He states that what was once just a number

(one hundred) now holds the characteristics of

honor.

3Ut turbae placuit, considunt armati (ch. 11).

4Tacitus mentions frameas in chs. 6 and 11. This

word has been associated with the ON þremjar,

double-edged sword (Width 1997:66), though it is

usually translated as spear, not sword.

5Online version of the Deutsches Rechtswörterbuch

(DRW): http://drw-www.adw.uni-heidelberg.de/

drw/. Accessed 13 June 2013.

6Suebos, postea quam per exploratores pontem fieri

comperissent, more suo concilio habito nuntios in

omnes partes dimisisse, uti de oppidis demigrarent,

liberos, uxores suaque omnia in silvis deponerent

atque omnes qui arma ferre possent unum in locum

convenirent (Caesar 4.19.2).

7Renovabant ibi leges, praecipus causas adiudicabant

et quid per annum essent acturi, sive in bello

sive in pace, communi consilio statuebant (Hucbaldus

1934:792).

8Online version of the Deutsches Rechtswörterbuch

(DRW): http://drw-www.adw.uni-heidelberg.de/

drw/. Accessed 13 June 2013.

9The areas cannot be safely identified, despite many

attempts having been made to do so. There is a tangible

coincidence of similarities between the person-

and place-names. This gives reason to suspect

that errors have been made during transcription.

10… ante regem aut in mallo publico legitimo hoc

est in mallobergo ante teoda aut thunginum (Lex

Salica; Eckhardt 1969:46, 6).