Journal of the North Atlantic

16

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

Introduction: The Outer Hebridean Iron Age

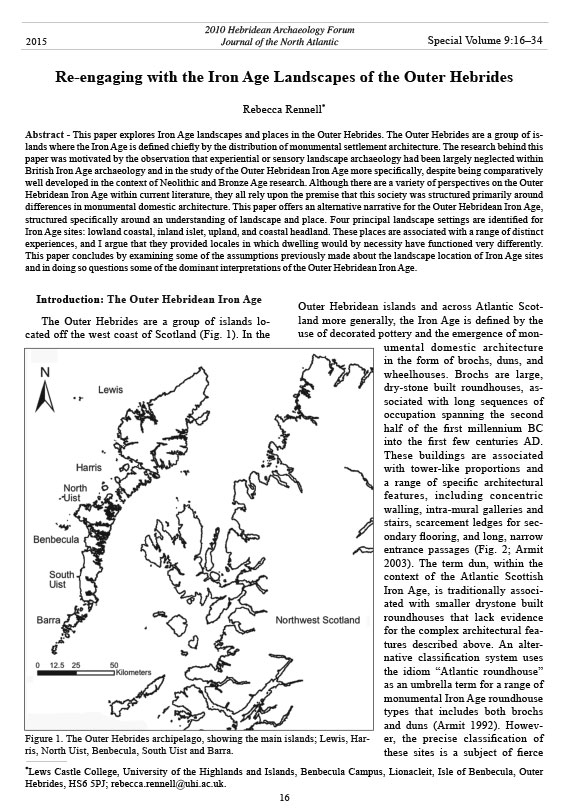

The Outer Hebrides are a group of islands located

off the west coast of Scotland (Fig. 1). In the

Outer Hebridean islands and across Atlantic Scotland

more generally, the Iron Age is defined by the

use of decorated pottery and the emergence of monumental

domestic architecture

in the form of brochs, duns, and

wheelhouses. Brochs are large,

dry-stone built roundhouses, associated

with long sequences of

occupation spanning the second

half of the first millennium BC

into the first few centuries AD.

These buildings are associated

with tower-like proportions and

a range of specific architectural

features, including concentric

walling, intra-mural galleries and

stairs, scarcement ledges for secondary

flooring, and long, narrow

entrance passages (Fig. 2; Armit

2003). The term dun, within the

context of the Atlantic Scottish

Iron Age, is traditionally associated

with smaller drystone built

roundhouses that lack evidence

for the complex architectural features

described above. An alternative

classification system uses

the idiom “Atlantic roundhouse”

as an umbrella term for a range of

monumental Iron Age roundhouse

types that includes both brochs

and duns (Armit 1992). However,

the precise classification of

these sites is a subject of fierce

Re-engaging with the Iron Age Landscapes of the Outer Hebrides

Rebecca Rennell*

Abstract - This paper explores Iron Age landscapes and places in the Outer Hebrides. The Outer Hebrides are a group of islands

where the Iron Age is defined chiefly by the distribution of monumental settlement architecture. The research behind this

paper was motivated by the observation that experiential or sensory landscape archaeology had been largely neglected within

British Iron Age archaeology and in the study of the Outer Hebridean Iron Age more specifically, despite being comparatively

well developed in the context of Neolithic and Bronze Age research. Although there are a variety of perspectives on the Outer

Hebridean Iron Age within current literature, they all rely upon the premise that this society was structured primarily around

differences in monumental domestic architecture. This paper offers an alternative narrative for the Outer Hebridean Iron Age,

structured specifically around an understanding of landscape and place. Four principal landscape settings are identified for

Iron Age sites: lowland coastal, inland islet, upland, and coastal headland. These places are associated with a range of distinct

experiences, and I argue that they provided locales in which dwelling would by necessity have functioned very differently.

This paper concludes by examining some of the assumptions previously made about the landscape location of Iron Age sites

and in doing so questions some of the dominant interpretations of the Outer Hebridean Iron Age.

Special Volume 9:16–34

2010 Hebridean Archaeology Forum

Journal of the North Atlantic

*Lews Castle College, University of the Highlands and Islands, Benbecula Campus, Lionacleit, Isle of Benbecula, Outer

Hebrides, HS6 5PJ; rebecca.rennell@uhi.ac.uk.

2015

Figure 1. The Outer Hebrides archipelago, showing the main islands; Lewis, Harris,

North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist and Barra.

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

17

debate, and remains as yet unresolved (Armit 1997a,

Harding 2004, Sharples 2006, Sharples and Parker

Pearson 1997, Sharples et al. 2004). Across Orkney,

a number of simple, thick-walled roundhouse

structures, associated with Early Iron Age dates

(ca. 800 BC–400 BC), have been interpreted as native

precursors to the broch tradition (Ballin-Smith

1994, Hedges 1987, Renfrew 1979, Sharples 1984).

However, the Early Iron Age remains fairly elusive

within the Outer Hebrides, and here the emergence

of monumental domestic architecture appears to be a

largely Middle Iron Age phenomenon (ca. 200 BC–

AD 400) (Armit 1990a, 1991). Both brochs and duns

are found widely across Atlantic Scotland, while

wheelhouses have a more discrete distribution, as

yet identified only in the Outer Hebrides and Shetland.

Wheelhouses are also drystone built roundhouses,

but are characterized by radial piers which

sub-divide the interior roundhouse space into small

bays, set around a central area (Fig. 3). The majority

of wheelhouses were revetted into the ground so that

they would have been occupied as semi-subterranean

buildings. Although not externally monumental

in the manner of the broch or dun, their elaborate

internal architecture suggests that wheelhouses were

also impressive, monumental buildings of their time.

There are examples of wheelhouses built into earlier

broch-type structures, both in the Outer Hebrides

(Armit 1998) and in Shetland (Hamilton 1956),

suggesting that wheelhouses replaced brochs as the

primary form of Iron Age dwelling. However, radiocarbon

sequences continue to extend the dates associated

with wheelhouse occupation from perhaps as

early as the 4th century BC (Barber 2003) into the 5th

centuries AD (Sharples 2012). Although questions

remain over the reliability of the earliest dates in this

sequence (ibid.), it has become apparent that there

was a significant degree of overlap between brochs

and wheelhouses in the Outer Hebrides, where they

are perhaps best viewed as broadly contemporary

Middle Iron Age settlements (Parker Pearson and

Sharples 1999:359).

The construction of brochs, duns, and wheelhouses

marks a change in attitudes to the home

and domestic architecture and is the culmination of

a process whereby monumental expression shifts

from more overtly “ritual” contexts to increasingly

“domestic” spheres of life (Armit and Finlayson

1992:670). A similar trend towards elaborate and

conspicuous Iron Age settlements can be identified

Figure 2. Dun Carloway, Lewis. A “classic” Iron Age broch..

Journal of the North Atlantic

18

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

within wider narratives of British prehistory (Haselgrove

and Pope 2007). Traditionally, brochs have

been interpreted as defensive structures (Childe

1935:204), a view still popularly held (Blythe

2005). However, over the last twenty years, purely

defensive explanations for these sites have been

increasingly challenged (Parker Pearson and Sharples

1999:350), reflecting wider trends within the

discipline (Fitzpatrick 1997; Hill 1989, 1995; Parker

Pearson 1996), and it is now more readily suggested

that the monumentality of these sites would have

represented social power, over and above the need to

defend territory (Armit 1997b:249), perhaps legitimized

through associations with earlier monumental

styles of architecture (Hingley 1996, 1999, 2005;

MacDonald 2008). Environmental change (Sharples

2006), population pressures (Armit 1990a), and economic

intensification (Dockrill 2002) have all been

cited as potential catalysts for this sudden desire for

monumental displays of power.

Largely as a consequence of the visual dominance

and impressive monumentality associated

with Middle Iron Age settlements, research in the

Outer Hebrides has tended to view and interpret Iron

Age society primarily through these buildings. Furthermore,

alternative interpretations of the relationship

between broch and wheelhouse communities

hinge largely upon debates about site classification

and associated problems of chronology. For example,

where sites are defined by a restricted number of

characteristics (MacKie 2006), the number of “true”

brochs remains small, leading to the interpretation

that these were elite residences, in comparison with

the more lowly wheelhouses (Parker Pearson and

Sharples 1999). Conversely, a more inclusive site

typology suggests that broch-type architecture may

have represented a fairly standard Iron Age dwelling

(Armit 2002). The Outer Hebrides offer unique

preservation conditions, which provides great scope

for reconstructing details of Iron Age life. For example,

extensive analysis of faunal and floral remains

(Bond 2002, Smith and Mulville 2004) and ceramic

residues (Campbell 2000, Campbell et al. 2004)

provide invaluable insight into Iron Age subsistence

and food-consumption practices. However, when the

data for the Outer Hebrides is considered as a whole,

Figure 3. One of the wheelhouses at The Udal, North Uist.

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

19

as yet there remains no clear distinction between

brochs, duns, and wheelhouses in this respect, and

instead these analyses point more readily towards

regional differences rather than site-type trends.

Nevertheless, the idea that differences in architecture

imposed the primary, underlying order to Iron

Age society persists, and frequently other forms of

material culture are forced to fit these predefined

categories.

Additionally, there has been a lack of interpretations

driven by an understanding of the archaeological

landscape. Notable exceptions include Scott’s

(1947) seminal paper “The problem of the brochs”,

Noel Fojut’s (1982) work on brochs in Shetland,

and Sharples and Parker Pearson’s (1997) discussion

of Iron Age landscapes across South Uist. What

remains absent, however, are specifically engaged

studies of sensory landscapes and the types of

landscape approach that are increasingly common

to other periods of British prehistory. While studies

of architectural space have begun to explore

the meaning and underlying structure of Iron Age

roundhouse dwellings (Foster 1989; Hingley 1984,

1995; Giles and Parker Pearson 1999; Parker Pearson

and Richards 1994; Parker Pearson and Sharples

1999:16–21), these buildings remain detached from

their landscape context. In fact, the view that Iron

Age dwelling constitutes the creation of meaningful

and symbolic spaces has not yet extended much beyond

the roundhouse wall. The scale and presence of

these sites demonstrate a considerable investment in

the Iron Age house, many in use over several generations.

Although rarely considered, this also involved

significant investment in place and the creation of

wider social landscapes. Occasionally, references

are made to the experiential qualities of Iron Age

site locations; the locations of Iron Age sites have

been described as “liminal” (Parker Pearson et

al. 2004:39) as well as “extreme” and “dramatic”

(Branigan and Foster 2002:84). In the absence of any

comprehensive study, however, it becomes problematic

when assertions about the experiential qualities

of place are used to reinforce arguments about the

structure of Iron Age society. In light of these observations,

my research set out to systematically

investigate Iron Age places and landscapes across

the Outer Hebrides, from a specifically experiential

landscape approach.

An Experiential Landscape Approach

The term experiential landscape archaeology

is used here to refer to research that explores the

experiential characteristics and sensory qualities

of archaeological landscapes and landscape locales

(or places). As an approach, experiential landscape

archaeology is grounded in social and spatial theories

that emphasize the importance of human scales

of experience. Although experiential approaches

tend to focus on more explicitly ritual or ceremonial

contexts (for example, Cummings and Whittle

2004, Cummings et al. 2011, Noble 2007), more

recently the relevance of this approach to everyday

or domestic settings has been increasingly explored

(Hamilton and Whitehouse 2006a, b; see also Rennell

2008). The importance of place and landscape in

the structuring of everyday life are ideas well developed

in Pierre Bourdieu’s (1977) Theory of Practice

and are encompassed in the term “dwelling” (Ingold

2000). Also of relevance is the work of sociologist

Anthony Giddens (1984) and the social geography

of Allen Pred (1984), both of whom develop upon

Hagerstrand’s theory of “Time-geography” and his

concern with the spatio-temporal character of daily

life. These ideas also articulate with a range of

phenomenological approaches within archaeology

(Tilley 1994, 2004) in which it is emphasized that

people come to know, understand, and act in the

world through their very physical experience of “being-

in-the-world” (Merleau-Ponty 1962).

Importantly, an interest in everyday experience

in the Outer Hebrides also requires that serious

thought is given to the island nature of these landscapes.

Despite a well-developed body of theory

relating to the archaeology of islands (Broodbank

2000, Noble et al. 2008, Rainbird 2007), these ideas

have yet to be fully integrated into our understanding

of the Outer Hebridean Iron Age. In the context

of my research, adopting an island approach meant

thinking about the way in which islands are defined,

perceived, and experienced and critically analyzing

the appropriateness of the island or group of islands

as a region of study (Rennell 2010a).

These arguments about place, landscape, and

islands informed the theoretical and methodological

framework for my research, which combined subject-

centered landscape survey and the use of GIS.

The subject-centered field survey involved engaging

with the Outer Hebridean landscape and investigating

and recording sensory qualities of Iron Age

places via a number of exploratory field practices.

In order to shift the emphasis away from architectural

typologies, the survey was not restricted to any

particular type of Middle Iron Age site, but explored

the full suite of monumental roundhouses associated

with this period: brochs, duns, and wheelhouses

(Fig. 4). An initial field survey was undertaken to

gather information about landscape location. This

Journal of the North Atlantic

20

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

approach included recording detailed descriptions

of the local topography, underlying geology, soil,

and vegetation, and an on-site assessment of environmental

changes that might have occurred over

the last two thousand years. As well as documenting

details about site location, records were made about

specific experiential qualities of place, in order to

test some of the assertions made within the archaeological

literature about the location of Iron Age sites.

This data included observations about visibility of

the sea, (Armit 1990b), the visibility of various environmental

zones (Cunliffe 1978; Parker Pearson et

al. 2004a, b), and scales of landscape visibility (Fojut

1982). A sub-sample of eight sites was then selected

for more detailed survey work. This follow-up effort

included field experiments designed to assess inter-

visibility and inter-audibility within these landscapes

and between Iron Age sites. GIS was used

as a subsequent means of mapping these places and

modelling aspects of visual experience.1 Continuous

viewshed models were generated as a method of

characterizing the potential visual experiences associated

with site locales. Continuous viewshed models

show the percentage of an area visible from all

locations within that area (Llobera 2003). In effect,

these models, based upon topographic data, provide

information on the visual qualities one is afforded

while moving throughout a specific landscape. A

series of cumulative viewshed models (Lake et al.

1998, Wheatley 1995) and heightened viewshed

models were generated to investigate the visibility of

roundhouse sites and the visibility from roundhouse

sites, using a series of hypothetic building heights.

When assessing the visibility of Iron Age sites in

the field, these experiments were restricted by the

preservation of each roundhouse, which in most

cases survived as mounds containing a few courses

of stone walling. Consequently, the field-based

research was unable to inform about the impact of

these buildings as specifically monumental structures.

Therefore, the purpose of the heightened and

cumulative view models was to explore how the potential

monumentality of these

buildings affected visual experience

within the landscape.

The overall methodology was

deliberately experimental, designed

to explore and develop

methods for experiential landscape

archaeology and, more

specifically, the potential for

combining subject-centered

field survey practices with the

use of GIS (for a more detailed

discussion of the experimental

methodology used, see Rennell

2009:Chapter 5, 2012).

By including the full range

of Iron Age sites from across

the Outer Hebrides, another

unique element of this research

was its geographical

breadth. Similar coverage of

the Iron Age material across

the Outer Hebrides has been

lacking since Ian Armit’s

(1992) publication of later

prehistoric settlement types

and in relevant chapters of his

later publication The Archaeology

of Skye and the Western

Isles (Armit 1996). Since these

publications, a large number

of excavations and survey projects

have been published that

contribute significantly to our

Figure 4. Distribution map showing the location of known broch, dun and wheelhouse

sites throughout the Outer Hebrides.

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

21

data indicates a decline in native woodland across

the islands from the early Holocene, with arboreal

species rapidly replaced by heathland vegetation

and the formation of peat (Birks and Masden 1979;

Bohncke 1988; Edwards and Brayshay 1996, 2000;

Edwards et al. 2000; Fossit 1996). By the Iron Age,

the island interior would have been defined by fairly

barren peat-based moorlands, dotted with small

lochs, giving way to more mountainous and rocky

areas on the east coast. In terms of these broad environmental

zones, the Iron Age landscape was similar

to the islands we find today (Fig. 5).

From as early as 400 BC, Iron Age communities

began building monumental roundhouses across

these island environments, creating a nexus of domestic

places that formed an integral part of the social

landscape. A large section of the Iron Age community

established their homes along the low-lying

coastal machair, an area that had been densely

occupied since the Late Bronze Age (Sharples et al.

2004). Iron Age communities also built roundhouses

within the island interior, on islets within inland

lochs. Increasing investigation suggests that islets

had been important places during the Neolithic,

which may have provided precedence for the establishment

of Iron Age settlements in these locations.

At the same time, a small number of monumental

roundhouses were built within upland landscapes or

on high coastal headlands. This range of locations

provided locales with distinctly different experiential

and sensory parameters, and dwellings in the

different types of locations would have functioned

in markedly different ways. In the following section,

I will describe some of the results of this research,

with reference to three of the case-study landscapes:

the Vallay Strand, a lowland coastal landscape in

North Uist (Fig. 6); Dun Bharabhat, an inland islet

site at Bhaltos, Lewis (Fig. 7); and the wheelhouse at

Cleitreabhal, within the upland landscapes of North

Uist (Fig. 8).

Lowland Coastal Landscape

Within lowland coastal landscapes, Iron Age

houses were built into the machair grasslands or

were located on islets within the lagoons or machair

lochs. In these parts of the landscape, houses tended

to be built in close proximity to one another, as at

the Vallay Strand. The Vallay Strand is a low-lying

area of coastal machair on the north coast of North

Uist, fronting a large area of inter-tidal sand flats

that separate the island of Vallay from North Uist

at high tide. During the Iron Age, however, this

inter-tidal zone was probably defined by expansive

understanding of the Outer Hebridean Iron Age.

To date, these projects have been largely discussed

within the context of smaller island regions: South

Uist (Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999), Barra and

associated islands (Branigan and Foster 2002), and

the Bhaltos peninsula, Lewis (Armit 2006, Harding

and Dixon 2000, Harding and Gilmour 2000). Based

upon my own research, and drawing upon this vast

dataset, the following section of this paper outlines

an alternative narrative for the Outer Hebridean Iron

Age structured around an understanding of place and

landscape.

A Landscape Narrative

The Iron Age environment in the Outer Hebrides,

forming the underlying skeleton to the social landscape,

was comprised of three distinct zones: rocky

coasts defined by thin acidic soils and sparse heathland

vegetation, coastal machair, and interior zones

of comparatively inhospitable peat-based moorland.

The machair is a unique type of ecological environment,

formed from wind-blown calcareous sands

and comprising a number of different landscape

elements, including dunes, grasslands, lagoons, and

hill machair (Angus 2001). The machair systems

probably began to take shape approximately 8000

years ago, formed through processes of erosion

and deposition caused by strong oceanic winds and

an excess of sand following deglaciation (Ritchie

1979). During the Iron Age, the machair defined

large parts of the west and northern coasts of the

islands and would have been the focus of agricultural

activity. However, since the Iron Age, erosion

and sea-level rise have caused extensive areas of

machair grasslands to flood and the coastline and

dunes to move progressively inland.

Evidence for sea-level rise (Ritchie 1966, 1979,

1985) suggest that during the Iron Age some current

islands, such as the islands of Uist, would have

been connected for large periods of the tidal cycle,

while others may have been linked by permanent

land-bridges. As has been widely acknowledged,

the island unit, although convenient for archaeologists,

does not necessarily correlate with the way in

which island communities interact with the spaces

around them and their experiences of island life.

This perspective is particularly pertinent in studies

of prehistoric communities. Instead, physical barriers

within the landscape are more likely to take the

form of mountain ranges, such as the mountains that

separate Harris from Lewis or the large hills on the

east coast of Uist, and large inland water systems,

such as Loch Be, also in South Uist. Pollen-core

Journal of the North Atlantic

22

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

Figure 5. Key environmental

zones across the Outer Hebrides

based on SNH landscape character

sssessment data.

Figure 6. Cumulative Viewshed model for Vallay Strand. Maps A and B show the location of the Vallay Strand and the

distribution of Iron Age roundhouses within this area. Map C shows the percentage of the surrounding landscape visible

from each location.

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

23

machair grasslands that have since flooded due to

rising sea levels and erosion of the coast. Along the

modern coastline of the strand are the remains of

three wheelhouses inserted into the remains of earlier

dun-type structures: Eilean Maleit, Garry Iochdrach,

and Cnoc a’Comdhalach. These sites were all

investigated by the antiquarian Erskine Beveridge

(1911) in the early part of the 20th century. In addition,

Eilean Maleit was partially excavated during

the 1990s, confirming Beveridge’s interpretation

of the site (Armit 1998). Pottery comparable with

material from wheelhouses at Cnip on Isle of Lewis,

Figure 7. Cumulative Viewshed model for Dun Bharabhat. Maps A and B show the location of the Bhaltos Peninsular and

the distribution of Iron Age roundhouses within this area. Map C shows the percentage of the surrounding landscape visible

from each location within this area.

Figure 8. Cumulative Viewshed model for Cleitreabhal. Maps A and B show the location of the Cleitreabhal and the distribution

of Iron Age roundhouses within this area. Map C shows the percentage of the surrounding landscape visible from

each location within this area.

Journal of the North Atlantic

24

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

the public and communal character of large parts

of these landscapes (Fig. 9A). Alternatively, the

closeness and lack of privacy may have meant that

boundaries between communities required strong

social expressions and concepts of territory, and land

ownership might have been emphasized in ways that

do not survive archaeologically. The continuous

viewshed models strengthen the interpretation of

these landscapes based upon field-survey data alone,

indicating fairly high visibility of the surrounding

landscape but also fluctuating and therefore

variable scales of visibility (Fig. 9). Hypothetical,

GIS-generated models of roundhouse visibility indicate

that within these low-lying landscapes there

was immense potential for increasing the visibility

of these sites by building outwardly monumental

roundhouses.

Tidal cycles would have dictated any shorebased

subsistence practices, such as the collection

of shellfish, shore-based fishing, and the collection

of seaweed for improving machair soils. Constant

sand movement, deflation and accretion, and the

general instability of coastal dunes would have been

major concerns. The importance of agricultural land

and the threat to these areas through longer-term

environmental changes would have increased competition

and claims to land between communities.

Seasonal cycles affecting the weather would also

have imprinted themselves on these places. Excavations

of several lowland coastal sites have indicated

that windblown sand was a persistent problem for

Allasdale on Isle of Barra, and Sollas on Isle of

North Uist point to occupation during the first few

centuries AD (ibid.). A possible wheelhouse is also

located further north still along the Vallay Stand

coastline, on the small headland at Geiriscleit. This

area also contains the remains of a number of earlier

prehistoric and later historic sites, including a

severely eroded Neolithic burial cairn located on

the edge of the current high-water mark (Dunwell

et al. 2003), a burnt mound and associated cellular

structures at Ceann nan Clachan (Armit and Braby

2002), as well as the remnants of numerous walls

and structures relating to an abandoned post-medieval

settlement.

Experiments in the field suggest that lowland

coastal landscapes, like the Vallay Strand, would

have been noisy and busy places to live. The sound

of people tending to nearby crops, animals, and children

and also the sound of the sea would have filled

these landscapes. From outside the roundhouse,

people would have been able to see other members

of the community working on the machair; tending

to crops, perhaps bringing animals back home for

slaughter. The sounds of people and their animals

at neighboring houses would have been heard on all

but the windiest of days and if not audible, then activities

around these places would have been highly

visible. There would have been limited privacy for

the occupants of these landscapes, and daily experiences

of these places would have strengthened the

strong social links between people, emphasizing

Figure 9. Panoramic photographs from: (A) Cnoc a’Comhdhalach, Vallay Strand, North Uist; (B) Dun Bharabhat, Bhaltos

Peninsular, Lewis; and (C) Cleitreabhal, North Uist.

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

25

have necessitated traversing a causeway, using a

boat, or wading through the water—very physical

experiences of the nature of separation from the

wider landscape. Although not the case at Bhaltos,

many islet settlements were remote or peripheral

to the more densely occupied lowland coastal landscapes,

and instead these places would have been

dominated by moorland environments. Proximity

to these environments suggest that communities

living on islets were likely to have been involved in

pastoral activities over other subsistence practices

that we associate with the Iron Age. The machair,

coast, and sea at the majority of islet sites would

have been some distance away and may well have

been regarded as peripheral, existing on the margins

of visual and audible communication. Therefore,

cultivation and care for these landscapes may not

have been principal concerns for the occupants

of islet sites. Hypothetical models of roundhouse

visibility indicate that these buildings would only

have marginally increased their visibility within the

surrounding landscape by constructing monumental

proportions, and in comparison with the machair

landscapes, there was limited potential for creating

visually impressive sites.

As with lowland coastal places, islet dwelling

would have encompassed dynamic characteristics—

excavation at Dun Bharabhat indicated that

the occupants regularly rebuilt the site in order

to combat the rising water levels (Harding and

Dixon 2000). Similar evidence was found at the

Neolithic islet site of Eilean Dòmhnuil in North

Uist (Armit 1996), indicating that these conditions

have persisted throughout prehistoric occupation

of these locales. Water levels will have changed as

a consequence of fluctuating periods of heavy rain

or drought, either on a seasonal basis or following

exceptional weather conditions. These transformations

would have affected the nature of these places

profoundly. The roundhouse may have been cut-off

from the shore for some if not lengthy periods of the

time, accentuating separation and removal from the

surrounding landscape. Water-based communications

were also potentially an intimate part of islet

dwelling in these parts of the landscape. Elsewhere

in the highlands, there is considerable evidence

for the use of log boats during this period (Mowat

1996), and given the suitability of these vessels to

the Outer Hebridean environment (McGrail 2001),

the lack of direct evidence should not preclude

discussions of the social implications of boat travel

within this island-based community (Farr 2006:90).

If the Iron Age occupants of these roundhouses had

access to log boats or other water-borne vessels, then

the occupants of these sites. At Cnip, the excavators

believe that adaptations to the original wheelhouse,

including an extended entrance passage and guard

cell, were modifications motivated by the need to

combat accumulating sands within the house (Armit

2006). Similarly, at The Udal, Crawford (ND) comments

on the problems of sand incursion at wheelhouse

B. Iron Age occupants of these lowland coastal

landscapes would therefore have been accustomed

to the dynamic nature of living in these places, and

this changing environment would have established

a particular tempo and series of concerns central to

living in these fragile machair locations.

Interior Islet Landscapes

By contrast, islet sites found within the island’s

interior would have been characterized by the restricted

nature of landscape visibility and experiences

of enclosure and isolation. Lochs within the island

interior, with their substantially defined banks, differ

from those on the coastal machair, which are often

more temporary bodies of water. The islet settlement

within Loch Bharabhat is a good example of this type

of site. This site was excavated during the 1980s as

part of an Edinburgh University-led research project

focusing on Later Prehistoric occupation at Bhaltos

(Armit and Harding 1990). This project included the

excavation of a broch at Loch na Beirigh (Harding

and Gilmour 2000), the wheelhouses at Cnip (Armit

2006), and the dun within Loch Bharabhat (Harding

and Dixon 2000). Another wheelhouse has been

identified on the Traigh na Berigh machair, and a

possible dun is located on the southern coast of the

peninsula (Fig. 7).

Although a number of broadly contemporary

Iron Age sites were built in fairly close proximity

to Dun Bharabhat, these other sites would not have

been visible from the islet, and the sound of people

at the nearby broch or wheelhouses, or people working

on the machair would not have been audible

(Fig. 9B). Similarly, the islet and the dun would have

been concealed or hidden from the surrounding landscape,

and people working in the wider landscape or

approaching this place would be invisible, beyond

the banks of the loch. The continuous viewshed

models generated for Dun Bharabhat highlight the

predominance of very low general visibility within

the landscape surrounding the islet (Fig. 7). Sounds

emanating from the roundhouse itself, even people

shouting, would have been contained within

the banks of the loch, echoing around the site and

further accentuating an impression of isolation and

seclusion. Access to areas beyond the islet would

Journal of the North Atlantic

26

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

this would have had a profound effect upon their

experiences, knowledge, and understanding of these

places and the wider landscape. The possibility that

islet dwellers were using boats also demands that we

review the concept of islet sites as detached or cutoff

from the surrounding landscape. Instead of experiencing

these places as physically or experientially

isolated, Iron Age people may well have regarded

these places as highly connected and dynamic locations.

These locations might also have provided Iron

Age occupants with links to other parts of the landscape

through the complex inland water systems that

would have dominated these Iron Age environments.

These alternative experiences and knowledge of

the landscape may well have reaffirmed differences

within the community between islet-dwelling and

lowland coastal-dwelling sections of this Iron Age

society.

Upland and Coastal Headland Sites

While the majority of the Iron Age community

appear to have created domestic places within lowland

coastal landscapes or on inland lochs, some

monumental architecture of this period was placed

within upland environments and on high coastal

headlands. These places shared a number of experiential

qualities that would have contrasted markedly

with places on the low-lying coastal machair zone

and the inland islets. For example, the wheelhouse

at Cleitreabhal is located on the slopes of a large hill,

providing extensive and uninterrupted views of the

wider landscape, as well as extensive views out to

sea (Fig. 9C). However, despite these visual qualities

and immediate proximity, these would not have

been places from where the sea was easily accessed.

The cumulative viewshed model for Cleitreabhal

highlights limited visibility of the local landscape

in contrast with the extensive views of regional and

distant locales (Fig. 8).

These fairly anomalous locations present the possibility

that these sites functioned in very different,

perhaps non-domestic, ways despite apparent similarity

in architecture. The relationship between the

wheelhouse at Cleitreabhal and the earlier chambered

cairn (Scott 1935) perhaps indicates that this site had

a special meaning or function with Iron Age society.

Discussion

The narrative presented above has attempted to

convey how Iron Age people might have engaged

with the landscapes and places that they inhabited.

I have offered an additional schema for investigating

the structure of Iron Age society based on the

sensory qualities of Iron Age places and landscapes

and argue that these places provided locales in

which dwelling would by necessity have functioned

very differently. The results of the field survey and

GIS-based modelling are summarized in Tables 1

and 2. The results of this research also questions

some of the assumptions previously made about the

landscape location of Iron Age sites and offers an

alternative perspective on this Iron Age society.

Iron Age sites, environment, and subsistence

practices

Parker Pearson and Sharples (1999:363) suggest

that wheelhouse-based communities were closely

tied to arable cultivation. In contrast, they envisage

a broch-dwelling elite living in comparatively

“marginal” areas of the landscape and engaged more

immediately with pastoralist practices. Currently,

however, there is an absence of evidence for brochs,

Table 2. Summary of GIS results by landscape location.

Lowland Coastal Islet Upland Coastal Headland

Continuous viewshed models

General landscape visibility High Low to mod Low High

Variation in landscape visibility Mod to high Low to mod Low High

Heightend viewshed models Significant Limited N/A Moderate

Cumulative viewshed models Significant Limited N/A Significant

Table 1. Summary of field survey results by landscape location.

Lowland Coastal Inland Islet Upland Coastal Headland

Inter-visibility between Iron Age site and surrounding landscape (>5 km) Mod Low Low Mod

Inter-audibility between Iron Age site and surrounding landscape (>5 km) High Low Low Low

Inter-visibility with nearby sites (>5 km) High Low N/A Mod

Inter-audibility with nearby sites (>5 km) High Low N/A Low

General description of landscape locale (>5 km) Local scale views, Intimate, Divided Open, exposed

variable experiences hidden

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

27

other complex roundhouses, duns, or wheelhouses

differing in terms of the scale of agricultural activities.

Wheelhouses, it is rightly observed, tend to be

located on the machair, which would have provided

the most suitable soils for cultivation; historically,

the machair has been the focus of agriculture across

the islands (Boyd and Boyd 1990, Lawson 2004) and

was also likely the prime location for agricultural

activities from as early as the Neolithic (Armit and

Finlayson 1992, Mills et al. 2004). However, brochs

and duns are also closely associated with these types

of landscape, and across the Outer Hebrides as a

whole, a direct correlation between architectural

typology and environmental/economic landscape

zones was not found to be the case. In fact, a principal

outcome of this research is the observation that

types of place and landscape cross-cut architectural

classification systems (Table 3). The types of place

identified as “lowland coastal” tended to be sites established

in close proximity to fertile machair grasslands,

suggesting that agricultural practices would

have been important to the subsistence practices of

these communities. My research also highlighted

strong sensory relationships between roundhouses

in these areas and what would have been cultivatable

machair surrounding these places. Many Iron Age

houses (e.g., wheelhouses) were constructed so that

they were physically embedded in the machair soil.

Perhaps similarly, at Dun Mhulan midden material

was allowed to accumulate outside the doorway of

the broch, eventually reaching up to 2m in height

(Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999). Midden material

from these houses was almost certainly used

to fertilize and improve the soils. These practices

would have emphasized the conceptual links between

the home and the agricultural potential of the

surrounding landscape.

In contrast, sites located on inland islets would

have been distant from the focal points of Iron Age

agriculture and in this respect would have been relatively

remote and isolated from these other areas

of occupation. Instead, it is likely that the occupants

of these sites would have focused on pastoral subsistence

practices—moving cattle and sheep among

grazing land and perhaps bringing them into the islet-

dwelling for winter byre or slaughter as suggested

by some excavations (Harding and Dixon 2000,

Parker Pearson and Sharples 1999). Historically,

islets have been used to segregate sections of grazing

herds at certain times of year, hence place names

within the Outer Hebrides such as “Soay”, meaning

“Goat Island” (Lawson 2004), and this nomenclature

suggests other ways in which islet landscapes might

have served a pastoral-based community. Alternatively,

the occupants of these sites would have had

stronger links with the moorland and potentially,

via interconnecting waterways, with the east coast

and moorland areas even further afield. Living in

these different parts of the landscape, the tempo and

catalysts for environmental change would have been

profoundly different to those affecting communities

dwelling within the lowland coastal landscapes.

These different subsistence practices and environmental

concerns would have distinguished these

communities and may have encouraged the development

of distinct senses of identity. Importantly,

this research suggests that differences within Iron

Age society were not necessarily structured solely

around choices in architecture, but also potentially

related to the types of landscapes in which people

made their homes and carried out their daily lives.

Although Parker Pearson and Sharples’ (1999) interpretation

represents an accurate assessment of the

Iron Age landscape across South Uist, this model of

Iron Age society is far less convincing when transposed

to neighboring island regions, such as North

Uist and Lewis. In particular, across North Uist, the

west coast distribution of sites is not as emphasized

as it is in South Uist, and here the distribution of

brochs and wheelhouses does not betray this distinct

relationship with these environmental zones.

Although wheelhouses have not been identified on

inland islets, they are found in the uplands as well as

low-lying coastal landscapes, while brochs and duns

were built in all of the four types of landscape location,

suggesting that subsistence practices cross-cut

existing classifications of Iron Age site types.

Island landscapes

As well as affording specific associations with

the various environmental zones across the Outer

Hebrides, the locations of Iron Age sites also likely

Table 3. Experience of place according to landscape location.

Uninterrupted views Good visibility

No. of sites of the sea and of local Sense of Atlantic roundhouse

surveyed wider landscape context landscape enclosure Broch Dun Wheelhouse

Upland 16 X X X X

Coastal headland 10 X X X -

Lowland coastal 32 - X X X X

Inland islet 94 - - X X X -

Journal of the North Atlantic

28

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

presumably focused towards more local concerns.

Both interpretations can be reconciled within this

study of place and landscape, suggesting that Iron

Age society was complex and potentially incorporated

varying social perspectives, identities, and social

practices.

The contrast between occupation of the low-lying

Atlantic coasts and dwelling within the more

easterly, island moorlands adds a further dimension

to Iron Age settlement patterns. A prevailing characteristic

of the Outer Hebridean island geography is

the vital contrast between the Atlantic west coast and

the Minch coast on the east and the potential these

areas of the island landscape would have afforded

Iron Age communities. Generally, the east coast

would have provided the principal areas for sheltered

and safe anchorage and thus the opportunity

for seafaring practices, perhaps relating to subsistence

such as deep-sea fishing, although evidence

for this is largely absent from the archaeological

record, or as means of communicating and accessing

wider areas for social reasons. In contrast, the west

coast of the Outer Hebrides would have provided

minimal opportunities for accessing the sea by boat,

but greater potential for a range of shore-based subsistence

activities such as collecting shellfish and

gathering seaweed and driftwood. The east and west

coasts would also have afforded distinctly different

opportunities for sensory experience. Across the Atlantic,

there is little between the Outer Hebridean islands

and the American continent, and this setting in

combination with a prevailing westerly wind, makes

for a distinctively exposed and windswept western

coastline. In comparison, while the landscape of

the east coast is far more rugged, the sea across the

Minch is less volatile, and this coastline is significantly

more sheltered. The major townships across

the islands—Castlebay, Lochboisdale, Lochmaddy,

Tarbet, and Stornoway—are all located on the east

coast. Today, these places function as important harbors

for the fishing industry as well as serving the

major ferries between the islands and the mainland.

In light of these differences, the density of Iron

Age occupation on the western coastline, within

what has been defined as lowland coastal landscapes,

prompts a number of questions. These sites

appear not to have been located in places where

people could easily view or monitor the sea. Neither

were these places associated with natural bays or

harbors, and it is unlikely then that experiences of

living in these landscapes provided an intimate link

with the sea, beyond the shore and coastline. Nevertheless,

the sea and coast would have been within

accessible distances. People would have been able

to hear the sea as well as sea birds, and the smell of

conveyed distinct experiences and relationships

with the wider island landscape. In particular, there

appears to have been a contrast between Iron Age

places dominated by views of the immediate locality

and with an inward/landward focus (primarily

lowland coastal and islet sites) and a minority of

places with views of the regional and distant landscapes

and specifically outward/seaward looking

perspectives (coastal headland and upland sites) (Table

4). In the case of the former, we might envisage

a specifically local understanding and knowledge of

landscape, with everyday experiences reinforcing

local, perhaps intra-island identities. Similarly, daily

activities might have been increasingly focused

within the immediate landscape, perhaps relating to

increasing investment in the immediate locality and

the intensification of localized subsistence practices.

In comparison, a smaller section of this Iron Age

society, living in places with wider views of the regional

landscape and perhaps extensive views out to

sea, might have associated themselves with a larger

social group—perhaps through seafaring activities

developing inter rather than intra-island concerns

and identities. Within coastal headland and upland

landscapes, daily activities had the possibility of

taking place within a wider area, perhaps involving

subsistence practices taking place further afield or

the procurement or movement of materials from

“other” places. Similarly contrasting interpretations

have been drawn from more traditional analysis

of Iron Age material. For example, both decorated

ceramics and monumental domestic architecture

indicate a high degree of cultural contact between

the Outer Hebrides and other island regions within

Atlantic Scotland during this period. Henderson

describes how contact enabled this area to become a

“recognisable zone, prone to simulating itself, (and)

creating broad similarities over long distances”

(Henderson 2000:150), suggesting an active relationship

between island communities and perhaps

a sense of shared inter-island regional identity. Alternatively,

Armit comments on the relative dearth

of imported Iron Age items, pottery or otherwise,

within the Outer Hebrides and highlights distinct

sequences in the development of monumental architectures

that distinguishes the Outer Hebrides from

wider Iron Age processes, as indicative of a progressively

“inward looking island people” (Armit 1996)

Table 4. Contrasting scales of island experience.

Local experiences Regional experiences

Land Sea

Intra-island identity Inter-island identity

Local material culture Regional material culture

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

29

to the themes raised in association with an “Island

Approach”, it appears that islet sites, like islands

more generally, can be understood to combine elements

of isolation and connectivity. These locations

might also have provided Iron Age occupants of

these sites with links to other parts of the landscape

through the complex loch and sea-loch systems that

would have dominated these Iron Age environments.

These alternative experiences and knowledge of the

landscape may well have reaffirmed differences between

islet-dwelling and lowland coastal-dwelling

sections of this Iron Age society.

Monumental architecture and place

This investigation into place and landscape experience

also questions some assumptions frequently

made about how Iron Age communities engaged

with monumental architecture. While brochs were

constructed to be highly visible and imposing from

the outside, wheelhouse sites were comparatively

modest buildings in this respect, yet similarly monumental

when viewed (or experienced) from within. It

has therefore been suggested, with reference specifically

to the location of Iron Age sites on the Bhaltos

peninsula, that wheelhouse sites were hidden within

the landscape, while Atlantic roundhouses were built

within more prominent places (Armit 2006:256).

However, my research suggests that the locations of

Iron Age sites provided quite different experiences.

Wheelhouse sites, predominantly located within

lowland coastal landscapes, were not found to be

within “hidden” locales. Instead the field survey

indicates that these places were highly communal,

easily accessible, and relatively exposed places in

the landscape. Brochs were found within a wider

variety of locales; however, sites built on islets within

freshwater lochs, such as Dun Bharabhat on the

Bhaltos peninsula, tended to be concealed within the

landscape. Analyzing the visibility of roundhouses

using varying height models within a GIS suggests

that even built to a height of 10 m (unlikely dimensions,

given the small diameter of Dun Bharabhat)

these places would still not have achieved the prominence

that has hitherto been described. This finding

suggests that brochs, when built on islets like Dun

Bharabhat for example, did not always function as

visually imposing sites. In contrast, brochs built

within lowland coastal and coastal headland settings

would have had much greater potential for visual

prominence. If the establishment of monumental domestic

architecture during the Iron Age is regarded

as a symbolic means of legitimizing rights to land,

demonstrating ownership, and local identity (Armit

1997b), how do these interpretations of place further

inform our understanding of Iron Age society? Perseaweed

and salt in the air would have been a constant

reminder of the sea’s proximity. Shell middens

associated with lowland coastal sites produce high

proportions of whelk (winkle) and limpet shells that

could have been collected by Iron Age communities

from these westerly shores. Evidence for deep-sea

fish is minimal across all Iron Age sites. The fish

bone assemblages from the Middle and Late Iron

Age sites at Dun Mhulan and Bornais, for example,

are dominated by small saithe, suggesting smallscale

subsistence fishing practice, probably carried

out largely from the shore (Cerón-Carrasco 1999,

Ingrem 2012). However, a general lack of fish-bone

analysis and minimal strategies for fish-bone retrieval

during excavation, mean that these results require

some further attention. On the basis of location,

however, it is unlikely that these communities had an

intimate relationship with the sea, beyond the confines

of the shore. In contrast, communities located

on the east coast would have had greater potential

for accessing the sea, involvement in sea-based as

opposed to shore-based subsistence practices, and

contact with mainland communities. Table 5 summarizes

some of the contrasting experiences, concerns,

and activities associated with east and west island

settlement.

Water-based communications were also potentially

an intimate part of islet dwelling in these parts

of the landscape. Little consideration has previously

been given to the use of boats in association with

these sites, perhaps on the basis that causeways precluded

their necessity. However, access to log boats

or other water-borne vessels by Iron Age occupants

of these roundhouses would have had a profound effect

upon their experiences, knowledge, and understanding

of these places and the wider landscape via

the complex maze of inland lochans, sea lochs, and

the sea itself. The possibility that islet dwellers were

using boats also demands that we review the concept

of islet sites as separated or cut-off from the surrounding

landscape. Instead of experiencing these

places as physically and experientially isolated, Iron

Age people might well have regarded these places as

highly connected and dynamic locations. Returning

Table 5. Contrasting experiences of east and west coast dwelling.

West East

Atlantic Minch

Land/coast Sea/Water

Agriculture Pastoralism

Shore collection Deep sea fishing?

Machair Moorland

Lowland coastal Islets

Public Private

Links with mainland

Journal of the North Atlantic

30

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

reuse of available stone. The fact that the entrance

to the chamber is maintained in the construction

of this site supports this interpretation. Crawford

(2002:127–128) has proposed that wheelhouse sites

had specifically “religious” as opposed to domestic

functions within Iron Age society. He draws attention

to evidence for votive deposits and to specific

elements of their architecture that he describes as

analogous to church or amphitheatre structures. Yet

wheelhouse excavations clearly demonstrate that

these sites were domestic buildings, occupied over

long periods of time, associated with a range of

recognizable “domestic” practices, albeit alongside

distinctively “ritual” behavior (Armit 2006, Barber

2003, Campbell 1991, Parker Pearson and Zvelebil

2014, Rennell 2010b, Sharples 2012). However, it

may well transpire that not all wheelhouse sites were

used primarily for domestic purposes and that different

uses of these buildings may have been deemed

more appropriate in certain landscape settings.

Conclusions

This paper has presented some alternative approaches

to interpreting Iron Age society in the

Outer Hebrides. I have identified a number of

different ways in which Iron Age sites were positioned

in the landscape and have explored the

variation of Iron Age experiences associated with

these places. I have suggested that differences in

the everyday experience of these places provided

alternative perspectives on the wider landscape. I

have also pointed out different ways in which monumental

architecture might have been experienced,

suggesting that creating visually imposing settlements

was not always a primary concern. In conclusion,

I argue that people’s everyday experiences

and perspective of the wider social landscape were

as important to Iron Age communities as similarities

or differences in the use of architectural styles.

Furthermore, these differing experiences affected

the manner in which communities identified themselves,

played out their day-to-day lives, and structured

social relationships.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on research carried out as part of

my doctoral thesis at the Institute of Archaeology, University

College London. This research was funded by the

AHRC and the Graduate School at the University College

London. I would like to thank my supervisors Professor

Sue Hamilton and Dr. Mark Lake for helping me develop

this research. I would also like to thank the two anonymous

reviewers for their valuable feedback and constructive

comments.

haps certain Iron Age communities sought to actively

harness these senses and experiences of isolation

associated with islet locations in order to separate

themselves from other parts of the community and

to reinforce and maintain their identity. Therefore,

the creation of domestic places within certain parts

of the landscape might have been a strategy, alongside

the establishment of distinctively elaborate and

monumental architecture, for demonstrating local

power.

The relationship between Iron Age sites and earlier

monuments may also have played a role in the

establishment of monumental architecture during

the Iron Age. There is growing evidence to suggest

that Iron Age communities across Atlantic Scotland

had a particular fascination and interest with these

ancestral landscapes (Hingley 1996, 1999, 2005;

MacDonald 2008; Sharples 2006). In particular, the

conspicuous chambered cairn monuments of Early

Neolithic communities may have had a particular

significance for Iron Age people. Across Orkney,

at least three recently excavated Maes-Howe type

tombs revealed Early Iron Age roundhouses built

within the Neolithic structures (MacDonald 2008).

Elsewhere in the Outer Hebrides, two Neolithic

burial tombs were reused as locations for Iron Age

roundhouses, and there is evidence that a number of

tombs were disturbed and perhaps re-used during

this period (Hingley 1996, 1999; Sharples 2006). In

fact, it has been argued that Iron Age monumental

domestic roundhouses across Atlantic Scotland,

brochs in particular, were built with direct reference

to the architectural forms of Early Neolithic burial

monuments, using links with the past to legitimize

a new social order (MacDonald 2008). Iron Age

places were obviously created within a landscape

that was already embedded with places of meaning,

significance, and culture. The burial monuments of

Early Neolithic communities, for example, would

have been prominent visual markers in the Iron Age

landscape. Similarly, the islet settlements of very

early island communities such as Eilean Dòmhnuill

and Eilean an Tighe, both on North Uist, were also

perhaps recognizable places within the Iron Age

landscape and may well have acted as templates for

Iron Age islet settlements.

The wheelhouse at Cleitreabhal is another example

that points to a relationship between Iron Age

sites and earlier landscape features. The uniqueness

of the landscape location of this wheelhouse and

the sensory qualities, landscape associations, and

removal from other areas of Iron Age settlement,

suggest that the re-use of the early chambered cairn

was a deliberate and defining factor in the construction

of this roundhouse rather than a fortuitous

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

31

Beveridge, E. 1911. North Uist: Its Archaeology and

Topography (Paperback edition 2001). Birlinn, Edinburgh,

UK.

Birks, H.J.B., and B.J. Madsen. 1979. Flandrian vegetational

history of Little Loch Roag, Isle of Lewis,

Scotland. Journal of Ecology 67:825–842.

Blythe, I. 2005. A military assessment of the defensive

capabilities of brochs. Pp. 246–253, In V.E. Turner,

R.A. Nicholson, S.J. Dockrill, and J.M. Bond (Eds.).

Tall Stories? 2 Millennia of Brochs. Shetland Amenity

Trust, Lerwick, UK.

Bohncke, S.J. 1988. Vegetation and habitation history

of the Callanish area, Isle of Lewis, Scotland. Pp.

445–461, In H.J. Birks, et al. (Eds.). The Cultural

Landscape: Past, Present, Future. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge, UK.

Bond, J.M. 2002. Pictish pigs and celtic cowboys: Food

and farming in the Atlantic Iron Age. Pp. 177–184, In

B. Ballin Smith and I. Banks (Eds.). In the Shadow

of the Brochs: The Iron Age in Scotland. Tempus,

Stroud, UK.

Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Boyd, J.M., and I.L. Boyd. 1990. The Hebrides: A Natural

History. Collins, London, UK.

Branigan, K., and P. Foster. 2002. Barra and the Bishop's

Isles: Living on the Margin. Tempus, Stroud, UK.

Broodbank, C. 2000. An Island Archaeology of the Early

Cyclades. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

UK.

Campbell, E. 1991. Excavations of a wheelhouse and

other Iron Age structures at Sollas, North Uist by

Aitkinson in 1957. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries

of Scotland 121:117–173.

Campbell, E. 2000. The raw, the cooked, and the burnt.

Archaeological Dialogues 72(2):184–198.

Campbell, E., R. Housley, and M. Taylor. 2004. Charred

food residues from Hebridean Iron Age pottery:

Analysis and dating. Pp. 65–85, In R. Housley and

G. Coles (Eds.). Atlantic Connections and Adaptations:

Economies, Environments, and Subsistence in

Lands Bordering the North Atlantic. Oxbow, Oxford,

UK.

Cerón-Carrasco, R. 1999. “The fish remains from Dun Vulan,

South Uist”. Pp. 118–134, In M. Parker-Pearson

and N. Sharples (Eds.). Between Land and Sea: Excavations

at Dun Vulan, South Uist. Sheffield Academic

Press, Sheffield, UK.

Childe, V.G. 1935. The Prehistory of Scotland. Kegan

Paul, London, UK.

Crawford, I.A. No date. The West Highlands and Islands,

a View of 50 Centuries: The Udal (N. Uist) Evidence.

Great Auk Press, Cambridge, UK.

Crawford, I. 2002. The wheelhouse. Pp. 274–281, In B.

Ballin Smith and I. Banks (Eds.). In the Shadow of the

Brochs: The Iron Age in Scotland. Tempus, Stroud,

UK.

Cummings, V., and A. Whittle. 2004. Places of Special

Virtue: Megaliths in the Neolithic landscapes of

Wales. Oxbow, Oxford, UK.

Literature Cited

Angus, S. 2001. The Outer Hebrides: Moor and Machair.

White Horse Press, Cambridge, UK.

Armit, I. 1990a. Monumentality and elaboration: A case

study in the Western Isles. Scottish Archaeological

Review 7:84–95.

Armit, I. 1990b. Brochs and Beyond in the Western Isles.

Pp. 41–70, In I. Armit (Ed.). Beyond the Brochs:

Changing Perspectives on the Atlantic Scottish Iron

Age. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, UK.

Armit, I. 1991. The Atlantic Scottish Iron Age: Five levels

of chronology. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries

of Scotland 121:181–214.

Armit, I. 1992. The later prehistory of the Western Isles

of Scotland. British Archaeological Reports. Archaeopress,

Oxford, UK.

Armit, I. 1996. The Archaeology of Skye and the Western

Isles. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, UK.

Armit, I. 1997a. Architecture and household: A response

to Sharples and Parker Pearson. Pp. 254–265, In C.

Haselgrove and A. Gwilt (Eds.). Reconstructing Iron

Age Societies. Oxbow (Monograph 71), Oxford, UK.

Armit, I. 1997b. Cultural landscapes and identities: A case

study in the Scottish Iron Age. Pp. 248–254, In C.

Haselgrove and A. Gwilt (Eds.). Reconstructing Iron

Age Societies. Oxbow (Monograph 71), Oxford, UK.

Armit, I. 1998. Re-excavation of an Iron Age wheelhouse

and earlier structure at Eilean Maleit, North Uist.

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

128:255–271.

Armit, I. 2002. Land and freedom: Implications of Atlantic

Scottish settlement patterns for Iron Age land-holding

and social organisation. Pp. 15–26, In B. Ballin Smith

and I. Banks (Eds.). In the Shadow of the Brochs: The

Iron Age in Scotland. Tempus, Stroud, UK.

Armit, I. 2003. Towers in the North: The Brochs of Scotland.

Tempus, Stroud, UK.

Armit, I. 2006. Anatomy of an Iron Age Roundhouse:

The Cnip Wheelhouse Excavations, Lewis. Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK.

Armit, I. and A. Braby. 2002. Excavation of a burnt mound

and associated structures at Ceann nan Clachan,

North Uist. Proceedings of the Scoiety of Antiquaries

132:229–258.

Armit, I., and B. Finlayson. 1992. Hunter-gatherers transformed:

The transformation to agriculture in North-

West Europe. Antiquity 66:604–676.

Armit, I., and D.W. Harding. 1990. Survey and Excavation

in West Lewis. Pp. 71–107, In I. Armit (Ed.).

Beyond the Brochs: Changing perspectives on the Atlantic

Scottish Iron Age. Edinburgh University Press,

Edinburgh, UK.

Ballin Smith, B. 1994. Howe: Four millenia of Orkney prehistory.

Excavations 1978–1982. Society of Antiquaries

of Scotland Monograph Series Number 9. Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK.

Barber, J.W. 2003. Bronze Age farms and Iron Age farm

mounds of the Outer Hebrides. Scottish Trust for Archaeological

Research (Monograph 4). Edinburgh, UK.

Journal of the North Atlantic

32

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

Hamilton, S., and R. Whitehouse. 2006a. Three senses of

dwelling: Beginning to socialise the Neolithic ditched

villages of the Tavoliere, southeast Italy. Iberian Archaeology

8:159–184.

Hamilton, S., and R. Whitehouse. 2006b. Phenomenology

in practice: Towards a methodology for a “subjective”

approach. European Journal of Archaeology

9(1):37–71.

Harding, D.W. 2004. The Iron Age in Northern Britain.

Routledge, London, UK.

Harding, D.W., and T.N. Dixon. 2000. Dun Bharabhat,

Cnip, an Iron Age settlement in West Lewis. Calanais

Research Series No. 2. University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh,

UK.

Harding, D.W., and S. Gilmour. 2000. The Iron Age

settlement at Beirgh, Riof, Isle of Lewis: Excavations

1985–1995. Calanais Research Series No. 1. University

of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Haselgrove, C., and R. Pope. 2007. Characterising the

Earlier Iron Age. Pp. 1–23, In C. Haselgrove and R.

Pope. (Eds.). The Earlier Iron Age in Britain and Beyond.

Oxbow, Oxford, UK.

Hedges, J.W. 1987. Bu, Gurness ad the Brochs of Orkney.

BAR Series, Oxford, UK.

Henderson, J. 2000. Shared traditions? The drystone settlement

records of Atlantic Scotland and Ireland: 700

BC to AD 200. Pp. 117–154, In J. Henderson (Ed.).

The Prehistory and Early History of Atlantic Europe.

Proceedings of the 4th European Association of Archaeologists

Annual Meeting. British Archaeological

Reports, Oxford, UK.

Hill, J.D. 1989. Re-thinking the Iron Age. Scottish Archaeological

Review 6:16–24.

Hill, J.D. 1995. Ritual and Rubbish in the Iron Age of

Wessex. Archaeopress, Oxford, UK.

Hingley, R. 1984. The archaeology of settlement and the

social significance of space. Scottish Archaeological

Review 1:16–23.

Hingley, R. 1995. The Iron Age in Atlantic Scotland:

Searching for the meaning of the substantial house. Pp.

184–194, In J.D. Hill and G. Cumberpatch (Eds.). Different

Iron Ages: Studies on the Iron Age in Temperate

Europe, British Archaeological Reports, International

Series 602. Archaeopress, Oxford, UK.

Hingley, R. 1996. Ancestors and Identity in the Later

Prehistory of Atlantic Scotland: The re-use and reinvention

of Neolithic monuments and material culture.

World Archaeology 28:232–243.

Hingley, R. 1999. The creation of later prehistoric landscapes

and the context of reuse of Neolithic and

Earlier Bronze Age monuments in Britain and Ireland.

Pp. 233–242, In B. Bevan (Ed.). Northern Exposure:

Interpretive Devolution and the Iron Age in Britain.

University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

Hingley, R. 2005. Brochs as markers in time. Pp. 97–105,

In V.E. Turner, R.A. Nicholson, S.J. Dockrill, and

J.M. Bond (Eds.). Tall Stories? 2 Millennia of Brochs.

Shetland Amenity Trust, Lerwick, UK.

Cummings, V., C. Henley, and N. Sharples. 2011. The

Chambered cairns of South Uist. Pp. 118–134, In M.

Parker Pearson (Ed.). From Machair to Mountains:

Archaeological Survey and Excavation in South Uist.

Sheffield Environmental and Archaeological Research

Campaign in the Hebrides. Volume 4. Sheffield University

Press, Sheffield, UK.

Cunliffe, B. 1978. Iron Age Communities in Britain, 2nd

Edition. Routledge, London, UK.

Dockrill, S.J. 2002. Brochs, Economy, and Power. Pp.

153–162, In B. Ballin Smith and I. Banks (Eds.). In

the Shadow of the Brochs: The Iron Age in Scotland.

Tempus, Stroud, UK.

Dunwell, A., M. Johnson, and I. Armit. 2003. Excavations

at Geirisclett chambered cairn, North Uist, Western

Isles. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of

Scotland 113:1–33.

Edwards, K., and B. Brayshay. 1996. Late glacial and Holocene

vegetational history of of South Uist and Barra.

Pp. 13–26, In D.D. Gilbertson, M. Kent, and J. Grattan

(Eds.). The Outer Hebrides: The Last 14,000 Years.

Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield, UK.

Edwards, K., and B. Brayshay. 2000. The vegetational

history of Barra. Pp. 310–318, In K. Branigan and P.

Foster (Eds.). From Barra to Berneray: Archaeological

Survey and Excavation in the Southern Isles of the

outer Hebrides. Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield,

UK.

Edwards K.J., Y. Mulder, T.A. Lomax, G. Whittington,

and K.R. Hirons. 2000. Human environmental interactions

in prehistoric landscapes: The example of

the Outer Hebrides. Pp. 13–32, In D. Hooke (Ed.).

Landscape: The Richest Historical Record. Society

for Landscape Studies, Supplementary Series 1.

Available online at http://www.landscapestudies.com/

index_files/HistoricalRecord.htm.

Farr, H. 2006. Seafaring as social action. Journal of Maritime

Archaeology 1:85–99.

Fitzpatrick, A.P. 1997. Everyday life in Iron Age Wessex.

Pp. 73–86, In A. Gwilt and C. Haselgrove (Eds.). Reconstructing

Iron Age Societies. Oxbow, Oxford, UK.

Fojut, N. 1982. Towards a geography of Shetland brochs.

Glasgow Archaeological Journal 9:38–91.

Fossit, J.A. 1996. Later Quaternary vegetation history

of the Western Isles of Scotland. New Phytologist

132:171–196.

Foster, S. 1989. Analysis of spatial patterns in buildings

as an insight into social structure. Antiquity 63:40–50.

Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline

of the Theory of Structuration. Blackwell Publishers,

Oxford, UK.

Giles, M., and M. Parker Pearson. 1999. Learning to live

in the Iron Age: Dwelling and praxis. Pp. 217–232,

In B. Bevan (Ed.). Northern Exposure: Interpretive

Devolution and the Iron Ages in Britain. Leicester

Archaeology Monographs. Leicester, UK.

Hamilton, J.R.C. 1956. Excavation at Jarlshof, Shetland.

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO), Edinburgh,

UK.

Journal of the North Atlantic

R. Rennell

2015 Special Volume 9

33

Ingold, T. 2000.The Perception of the Environment: Essays

in Livelihood, Dwelling, and Skill. Routledge,

London, UK.

Ingrem, C. 2012. Resource exploitation: The sea. Pp.

157–158, In N.A. Sharples (Ed.). Norse Farmstead in

the Outer Hebrides: Excavations at Mound 3, Bornais,

South Uist. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK.

Lake, M., P. Woodman, and S. Mithen. 1998. Tailoring

GIS software for archaeological applications: an

example concerning viewshed analysis. Journal of

Archaeological Science 25:27–38.

Lawson, B. 2004. North Uist in History and Legend. John

Donald Publishers, Edinburgh, UK.

Llobera, M. 2003. Extending GIS-based analysis: The

concept of visualscape. International Journal of Geographic

Information Science 1(17):1–25.

MacDonald, K. 2008. The role of the past in the Bronze

and Iron Ages of the northern and western islands of

Scotland. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. Sheffield University,

Sheffield, UK.

MacKie, E. 2006. The roundhouses, brochs, and wheelhouses

of Atlantic Scotland c. 700 BC–AD 500: Architecture

and material culture. British Archaeological

Reports. Archaeopress, Oxford, UK.

McGrail, S. 2001. Boats of the World from the Stone Age to

Medieval times. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Mills, C.M., I. Armit, K.J. Edwards, P. Grinter, and Y.

Mulder. 2004. Neolithic land-use and Environmental

Degradation: a study from the Western Isles of Scotland.

Antiquity 78:886–895.

Merleau-Ponty, M. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception.

Routledge, London, UK.

Mowat, R.J.C. 1996. The Logboats of Scotland. Oxbow

Books, Oxford, UK.

Noble, G. 2007. Harnessing the waves: Monuments and

ceremonial complexes in Orkney and beyond. Journal

of Maritime Archaeology 1:100–117.

Noble, G., T. Poller, J. Raven, and L. Verrill (Eds.). 2008.

Scottish Odysseys: The Archaeology of Islands. Tempus,

Stroud, UK.

Parker Pearson, M. 1996. Food, fertility, and front doors

in the first millennium BC. Pp. 17–132, In T. Champion