2008 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 15(3):417–430

Demography of an Island Population of Spotted Turtles

(Clemmys guttata) at the Species’ Northern Range Limit

Dan J. Reeves1 and Jacqueline D. Litzgus1,*

Abstract - Demographic information from geographically isolated conspecific

populations is important for understanding how a species is locally adapted, and can

thus inform conservation decisions. Clemmys guttata (Spotted Turtle) is declining

throughout its range in eastern North America due to habitat loss and fragmentation

and collection of specimens for the pet trade. The objectives of our study were

to describe the demography of a previously unstudied island population of Spotted

Turtles and to make comparisons to conspecific mainland populations. We conducted

mark-recapture surveys for turtles on a small (23.2-ha) island in eastern Georgian

Bay, ON, Canada. Over seven sampling trips, 40 different turtles were captured 72

times: 23 females, 6 males, 10 juveniles, and 1 hatchling. Males had significantly

larger straight-line carapace lengths and contour carapace lengths than females,

whereas females had greater carapace heights than males. Adult females on the island

were significantly smaller than females on the mainland. Density was estimated to be

1.7 turtles/ha for the entire island, and 21.4 turtles/ha in one wetland where turtles

aggregated in spring. The adult sex ratio was significantly skewed in favor of females

(1 male: 3.83 females). Our study provides information on the population ecology of

Spotted Turtles in isolation, which is important for the creation of management plans

for populations being fragmented by human activities.

Introduction

Natural history and life-history characteristics can differ among conspecific populations. Therefore, demographic information from geographically

isolated populations is important for understanding how a species varies

over its range, and can shed light on the environmental conditions that have

led to locally adapted traits. Clemmys guttata Schneider (Spotted Turtle)

is a relatively widely distributed species in eastern North America, with

disjunct populations ranging from Maine southward along the Atlantic

Coastal Plain to central Florida (Barnwell et al. 1997, Ernst et al. 1994),

and westward along the southern shores of the Great Lakes from Ontario to

Illinois (Wilson 1994). The Spotted Turtle is considered vulnerable, threatened,

or endangered throughout its range; populations are thought to be

declining largely due to habitat destruction and harvesting for the pet trade

(Ernst et al. 1994, Litzgus 2004, Lovich 1989, Lovich and Jaworski 1988).

The species was recently up-listed from Special Concern to Endangered in

Canada by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

(COSEWIC; Litzgus 2004). A few geographically separated populations

have been relatively well-studied (e.g., Chippindale 1989; Cook et al. 1980;

1Department of Biology, Laurentian University, Sudbury, ON, P3E 2C6, Canada.

*Corresponding author - jlitzgus@laurentian.ca.

418 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 3

Ernst 1970, 1976; Haxton and Berrill 1999; Litzgus and Brooks 1998a,

1998b, 2000; Litzgus and Mousseau 2004a, 2004b, 2006; Litzgus et al.

1999; Seburn 2003); however, there have not been any studies conducted on

isolated island populations. Studying island populations can provide insight

into how isolation affects population ecology, which will be important in

understanding population persistence in the face of habitat fragmentation

that leads to isolated populations. Thus, information on the demography of

island populations is important to the conservation of endangered species.

The objectives of our study were to describe the demography of a previously

unstudied island population of Spotted Turtles and to make comparisons to

other conspecific mainland populations.

Field Site Description

The study was conducted on a small (23.2-ha), privately-owned island

along the east coast of Georgian Bay, ON, Canada. The island is isolated

from the mainland by a minimum of 900 m of deep, open water and is approximately

50 m from the closest island, which is small and farther away

from the mainland. The study island is at the same latitude (45oN) and is 10

km away from a mainland population of Spotted Turtles that has been the focus

of an ongoing long-term (30-year) mark-recapture study (Litzgus 2006;

Litzgus and Brooks 1998a, 1998b, 2000; Litzgus et al. 1999). The mainland

site has been previously noted as an island, but due to low water levels in

Georgian Bay, has been connected to the mainland by a short portage since

at least 1991. In addition, even when the site was historically an island, it

was separated from the mainland by about a 3-m wide channel of shallow

water, and thus was not isolated from the mainland in terms of accessibility

by Spotted Turtles. The island site was discovered while conducting reconnaissance

surveys for previously unknown populations of Spotted Turtles in

the summer of 2005.

The habitats on the island are typified by elevated, exposed rock outcrops

that are dotted with small pools of shallow water and small patches of upland

forest, and a large shrub swamp that is located in the center of the island.

Upland forest type on the island was classified using the Forest Ecosite Classification System (Chambers et al. 1997) as 14.1, which is characterized by

Pinus strobus Linnaeus (White Pine)–Populus grandidentata Michx. (Bigtooth

Aspen)–Quercus rubra Linnaeus (Red Oak)–dominated stands on dry

to moderately fresh soil. Vegetation type was determined to be 28 using the

Forest Ecosite Classification System (Chambers et al. 1997). The understory

consists of moderate levels of hardwood and conifer regeneration, including

Acer rubrum Linnaeus (Red Maple), Abies balsamea (L.) Mill. (Balsam

Fir), White Pine, and Red Oak, and hardwood shrubs such as Corylus cornuta

Marsh (Beaked Hazel), Vaccinium angustifolium Aiton (Lowbush Blueberry),

Gaultheria procumbens Linnaeus (Wintergreen), and Lonicera canadensis

Bartram ex Marsh (Fly Honeysuckle). Forest stands were commonly interrupted

by areas with an open canopy, consisting of sections of bare rock with

2008 D.J. Reeves and J.D. Litzgus 419

patches of Juniperus communis Linnaeus (Juniper), Deschampsia flexuosa

(L.) Trin. (Hairgrass), Cladina rangiferina Linnaeus (Reindeer Lichen), and

assorted moss species. A 0.42-ha wetland where many turtles were captured

consisted mainly of Sphagnum spp., Chamaedaphne calyculata (L.) Moench

(Leatherleaf), Gaylussacia baccata (Wangenh) K. Koch (Huckleberry), Vaccinium

macrocarpon Aiton (Large Cranberry), Aronia melanocarpa (Michx.)

K.R. Robertson & Phipps (Black Chokecherry), Lowbush Blueberry, and a

variety of floating algae. Rock pools of various sizes (from approximately 0.2

m2 to 5 m2) dotted the west side of the island. These rock pools were generally

devoid of vegetation, but sometimes contained aquatic algae and sphagnum

moss. Other reptile and amphibian species noted on the island included: Pantherophis

[Elaphe] gloydi Conant (Eastern Fox Snake), Thamnophis sirtalis

sirtalis Linnaeus (Eastern Garter Snake), Chrysemys picta Schneider (Painted

Turtle), and Rana clamitans Latreille (Green Frog). The island is privately

owned and has three cottages which are used seasonally, each with a dock onto

Georgian Bay.

Methods

We used mark-recapture techniques to study the Spotted Turtles of the island

site. We made a total of seven visits to the island between June 2005 and

September 2007 (Table 1). Turtles were captured by hand while researchers

walked the site; there were typically two researchers searching for turtles on

each sampling visit. Upon initial capture each year (2005, 2006, and 2007),

turtles were marked (Cagle 1939) if previously un-captured, weighed using

a 300-g (± 2 g) Pesola spring scale, and midline (straight-line) carapace

length and width, midline (straight-line) plastron length and width, and

carapace heights were measured to 0.1 mm with calipers (± 0.05 stainless;

Scherr-Tumico, China). Capture location was recorded with a hand-held

GPS (Garmin Legend, Olathe, KS). Any injuries were sketched and noted.

Sex was determined using secondary sexual characteristics (Ernst et al.

1994) and recorded; females were palpated to check for gravidity. Turtles

Table 1. Date of visits to an island site in eastern Georgian Bay, ON and number of Spotted

Turtles (Clemmys guttata) captured and marked. * indicates sampling dates used in population

size estimate (see Table 4). MR = marked recaptures.

Females Males Juveniles

Total captures Total captures Total captures

Date of visit (new captures) MR (new captures) MR (new captures) MR

10 June 2005 4 (4) 0 2 (2) 0 4 (4) 0

15 May 2006 3 (3) 0 0 (0) 0 2 (1) 1

20 June 2006 * 14 (8) 6 2 (2) 0 6 (3) 3

21 June 2006 * 7 (4) 3 1 (1) 0 3 (0) 3

6 July 2006 4 (2) 2 0 (0) 0 0 (0) 0

22 July 2006 * 9 (1) 8 2 (0) 2 5 (2) 3

10 September 2007 2 (1) 1 1 (1) 0 1 (1) 0

Totals 43 (23) 20 8 (6) 2 21 (11) 10

420 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 3

captured in 2006 were also measured for midline contour carapace and contour

plastron length to account for the concavity of the male plastron (Ernst

et al. 1994) with a flexible measuring tape (±1 mm).

We tested for significant differences between males and females with

respect to carapace length (CL), carapace width (CW), contour carapace

length (CCL), plastron length (PL), plastron width (PW), contour plastron

length (CPL), carapace height (CH), and body mass using independent

sample t-tests. We tested whether the sex ratio differed from parity using

a chi-square (χ2) analysis. Adult population size was estimated using three

sampling dates (Table 1) and the CAPTURE2 program (Hines 1998). We

used the Schnabel (1938) Mt time variation model, which is a direct extension

of the Lincoln-Peterson model, to estimate population size (Braun

2005). The model assumes that: 1) the population is closed; 2) all animals

are equally likely to be captured in each sample; and 3) marks are not lost,

gained, or overlooked. Only adult turtles (carapace length of >102 mm

for females and >105 mm for males; from Litzgus and Brooks 1998b) that

showed secondary sexual characteristics (Ernst et al. 1994) were used in

the population-size estimate.

We tested for body-size variation between the island population and

the mainland population of Spotted Turtles noted above. Only adult female

turtles from each population were used due to the small number of males

captured in the island population (Table 1). We tested for body-size differences

between the island and mainland females using independent samples

t-tests. Adult female size ratios were calculated by dividing mean mainland

female measurement by mean island female measurement.

Results

Forty different Spotted Turtles were captured a total of 72 times over

seven visits (Table 1) to the island site: 23 females, 6 males, and 11 juveniles

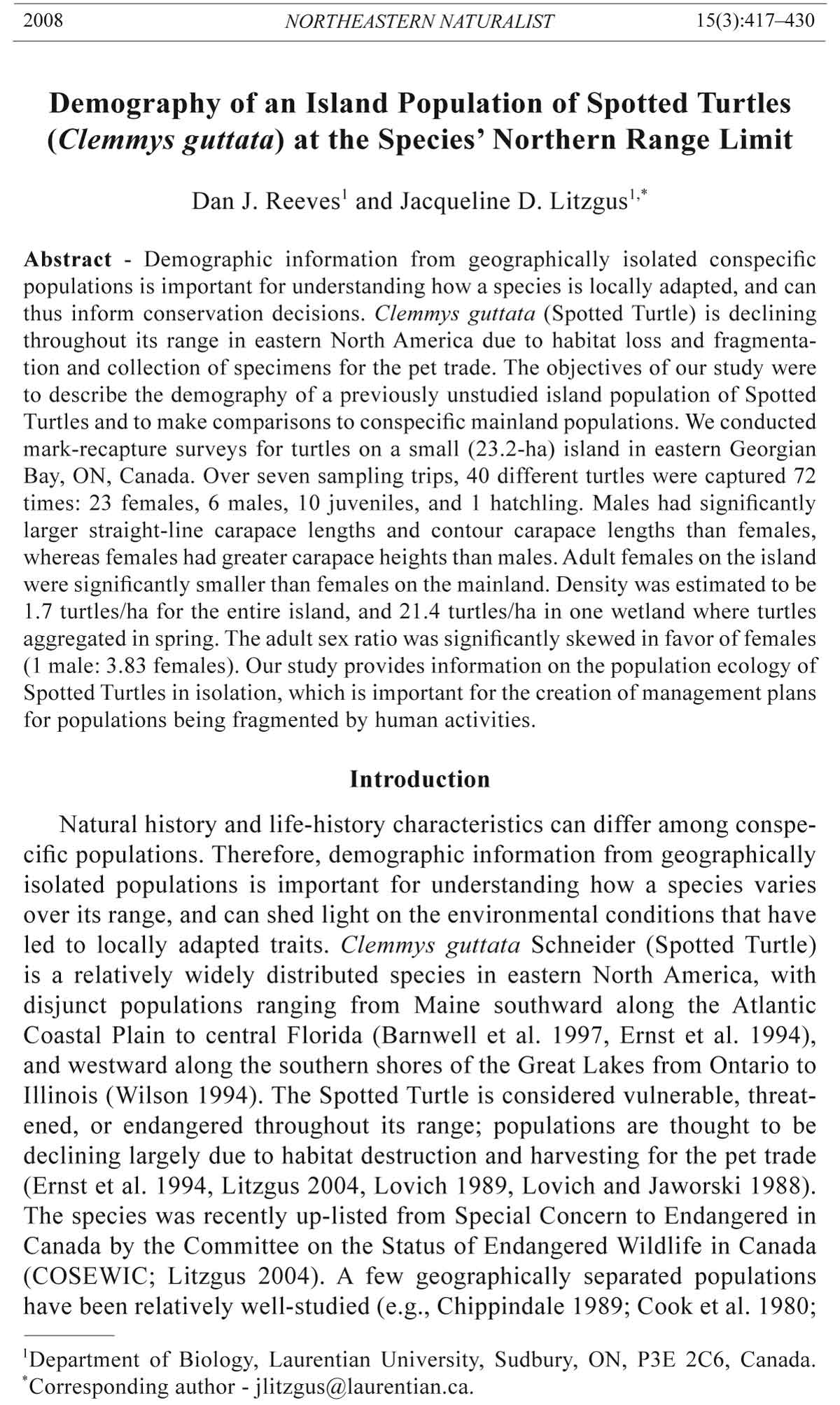

(including 1 hatchling; Fig. 1). The adult sex ratio was 1 male: 3.83 females,

which differed significantly from 1:1 (χ2 = 9.96, df = 1, P < 0.005). Five

adults (17% of adult population) and one juvenile (9% of juvenile population)

had missing limbs, and three adult females had stubbed tails (10%

of adult population); no adult males or juveniles with stubbed tails were

observed. Seventy-five percent of females (3 of 4) collected in 2005 were

gravid, and 19% (4 of 21) of females collected in 2006 were gravid. None of

the four females captured in both 2005 and 2006 was determined to be gravid

in successive years. There was no significant size dimorphism between adult

males and females with respect to CW, PL, PW, CPL, or body mass (P > 0.05

in all cases; Table 2). Males had significantly greater CL (t = -3.43, df = 27,

P < 0.005) and CCL (t = -3.21, df = 18, P < 0.005) than females. However,

females had greater CH than males (t = 3.58, df = 27, P < 0.005). Mainland

females were significantly larger than island females in every trait measured

(size ratios > 1 in all cases; Table 3). Estimated adult population size on

the island was 31 turtles, and adult density was estimated to be 1.7 turtles/

2008 D.J. Reeves and J.D. Litzgus 421

ha (Table 4). During one sampling period (22 July 2006), nine turtles were

found in the 0.42-ha wetland noted above, giving a density of 21.4 turtles/ha

in this wetland.

An unusual aspect of the ecology of the island population of Spotted

Turtles was the turtles’ use of rock pools during the active season. Of the 72

total captures, 44 (61%) occurred in rock pools; 24 female captures, 5 male

captures, and 15 juvenile captures were from rock pools. A total of 20 (28%)

of the captures occurred in the 0.42-ha wetland.

Figure 1. Body-size (midline carapace length) frequency distribution of Spotted

Turtles (Clemmys guttata) captured from an island site in eastern Georgian Bay, ON,

Canada. Each turtle is represented once by its size at most recent capture.

Table 2. Mean body size measurements ± standard errors for adult Spotted Turtles (Clemmys

guttata) captured from an island population in eastern Georgian Bay, ON, Canada over seven

visits between June 2005 and September 2007. Each individual is represented once by its size

at most recent capture. * indicates a significant difference between the sexes (see text for statistical

results).

Body-size variable Females Males

Carapace length (cm)* 10.89 ± 0.07 (N = 23) 11.70 ± 0.25 (N = 6)

Carapace width (cm) 8.35 ± 0.06 (N = 23) 8.68 ± 0.18 (N = 6)

Plastron length (cm) 9.68 ± 0.06 (N = 23) 9.70 ± 0.18 (N = 6)

Plastron width (cm) 6.14 ± 0.04 (N = 23) 6.12 ± 0.16 (N = 6)

Contour carapace length (cm)* 11.97 ± 0.10 (N = 18) 12.82 ± 0.34 (N = 4)

Contour plastron length (cm) 9.74 ± 0.07 (N = 18) 9.60 ± 0.29 (N = 4)

Carapace height (cm)* 4.07 ± 0.04 (N = 23) 3.71 ± 0.08 (N = 6)

Body mass (g) 212.18 ± 4.08 (N = 22) 219.83 ± 7.73 (N = 6)

422 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 3

Table 4. Comparison of Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) population sizes (method of estimation) and densities across the species’ range. Approximate latitudes

of population locations are given in parentheses.

Population size Number of

Location (latitude) (model used) turtles captured Density (turtles/ha) Source

Beidler Forest, SC (33oN) 36 (Lincoln index) 33 0.36 Litzgus and Mousseau 2004

Lancaster County, PA (40oN) 258 (Lincoln index) 180 79.60 Ernst 1976

Lockport Pr., IL (41.5oN) 258 (Schnabel) 98 2.20 Wilson 1994

Victoria County, ON (44oN) 55 (Lincoln index) 26 0.46 Haxton 1998

Mainland, Georgian Bay, ON (45oN) 187 (Peterson) 94 0.62 Litzgus 1996

Island, Georgian Bay, ON (45oN) 31 (Schnabel Mt) 27 1.34 Current study

Table 3. Means (ranges) and size ratios for morphological traits of female Spotted Turtles (Clemmys guttata) from an island (current study) and a mainland site

(J.D. Litzgus, unpubl. data). The results of independent t-tests for differences between populations are also provided. Units for all traits are cm, except g for mass.

Size ratios were calculated as mean mainland trait divided by mean island trait. Mainland turtles were significantly larger than island turtles in all traits.

Mainland Island

Trait N Mean (range) N Mean (range) Size ratio t-value P-value

Carapace length 66 11.57 (11.50–11.63) 21 10.88 (10.81–10.96) 1.062 5.82 less than 0.001

Carapace width 63 8.71 (8.66–8.76) 21 8.34 (8.28–8.40) 1.044 4.02 less than 0.001

Plastron length 66 10.16 (10.10–10.22) 21 9.68 (9.61–9.74) 1.049 4.32 less than 0.001

Plastron width 63 6.57 (6.53–6.61) 21 6.14 (6.09–6.18) 1.071 5.94 less than 0.001

Carapace height 38 4.37(4.34–4.41) 21 4.08 (4.04–4.11) 1.072 5.15 less than 0.001

Contour carapace length 38 13.25 (13.17–13.33) 18 11.97 (11.86–12.07) 1.107 8.48 less than 0.001

Contour plastron length 10 10.61 (10.52–10.70) 18 9.74 (9.68–9.81) 1.089 7.84 less than 0.001

Body mass 65 238.51(235.22–241.80) 20 212.38 (208.11–216.66) 1.123 4.16 less than 0.001

2008 D.J. Reeves and J.D. Litzgus 423

Discussion

The majority of turtles captured at the island site were adults (28% of the

40 captures were juveniles). This finding is consistent with juvenile capture

rates in other populations across the Spotted Turtle’s range, but is one of

the highest values reported. Both at the mainland site in Georgian Bay, ON

(Litzgus 1996) and in a South Carolina population (Litzgus and Mousseau

2004b), 14% of the captures were juveniles. In Massachusetts, 18% of captures

were juveniles (Graham 1995), in Illinois up to 33% of annual captures

were juveniles (Mauger 1990, 2004), and a 13% juvenile capture rate was

observed in Pennsylvania (Ernst 1976). Juvenile Spotted Turtles tend to be

more secretive and use different habitats than adults (Chippendale 1984,

Ernst 1976), which can result in low capture rates for juveniles. On the other

hand, low capture rates of juveniles may reflect low proportions of juveniles,

which are expected for bet-hedging species (Roff 1992, Stearns 1976).

However, we found relatively high juvenile numbers in the island population

compared to most previous studies, which suggests that juveniles were readily

captured, perhaps because suitable habitat for hiding is a limiting factor

for juveniles at the island site.

The adult sex ratio of the island population differed significantly from

equality; it was heavily biased towards females. In contrast, most previous

population ecology studies of Spotted Turtles found equal sex ratios (e.g.,

Graham 1995, Litzgus and Mousseau 2004b, Mauger 1990, McGee et al.

1989), including the closest mainland population (Litzgus 1996) to our island

site. There are, however, other Spotted Turtle populations with skewed

sex ratios favoring females (e.g., Haxton 1998 [1 male: 1.9 females]; Seburn

2003 [1 male: 3.5 females]), but none to the degree seen in our island population.

One possible explanation is related to the fact that Spotted Turtles exhibit

temperature sex determination, with lower egg incubation temperatures

(22.5 to 27.0 oC) producing predominantly males, and higher temperatures

(30 oC and above) producing 100% females (Ewert and Nelson 1991). Due

to the relatively open canopy and shallow soils over bedrock present on

the island, nesting may be limited to areas with high substrate temperature,

thus skewing the sex ratio towards females. However, Spotted Turtles at the

nearby mainland site also use open-canopy rock outcrops for nesting sites

(Litzgus and Brooks 1998a, 2000) similar to those on the island, but the

mainland population does not exhibit an unequal sex ratio (Litzgus 1996).

Sampling bias can result in unequal sex ratios, and Spotted Turtle females

and males use different habitats during some parts of the active season (Litzgus

and Brooks 2000), so sampling efforts focusing on one type of habitat at

one time of year could target one sex, influencing the sex ratio. For example,

female Spotted Turtles may be more readily captured during the nesting

season (mid-late June at the latitude of the island site; Litzgus and Brooks

1998a) when they tend to be more active than males (Litzgus and Mousseau

2004a, Morreale et al. 1984). However, we captured relatively few female

turtles on some sampling dates during the nesting season (e.g., 10 June 2005,

424 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 3

21 June 2006), and many female turtles outside of the nesting season (e.g.,

22 July 2006; Table 1). Furthermore, our sampling efforts encompassed

several months (May, June, July, and September) during the active season,

reducing the chances of a temporal bias, and we surveyed different habitat

types at each visit. We conclude that it is unlikely that the skewed sex ratio in

the island population is due to temporal or habitat sampling bias, but instead

reflects a real deviation from equality. Future studies should confirm the sex

ratio skew and examine possible explanations for the female-biased ratio.

Spotted Turtles in the island population showed relatively high injury

rates. Commonly reported injuries in turtles include tail loss and partial or

complete amputation of limb(s). For example, Glyptemys insculpta (Le-

Conte) (Wood Turtles) have been reported to have 24.5% tail injury rates and

9.6% limb amputation rates (Walde et al. 2003). Limb amputation is typically

due to predation (e.g., Carroll and Ultsch 2006, Harding 1985, Harding

and Bloomer 1979); however, turtles of the genera Clemmys and Glyptemys

are known to cause conspecific tail damage during agonistic encounters

(Ernst 1967, Kaufmann 1992). Spotted Turtles are known to exhibit forced

insemination (Ernst 1976, Ernst and Barbour 1972), which may explain why

all turtles with stubbed tails in our population were female. The proportion

of adults in the island population with missing limbs (17%) was higher than

that (5.8%) reported by Ernst (1976) for his Pennsylvania population. The

prevalence of missing limbs in the island population may be due to higher

catchability of injured animals, or may reflect a lack of suitable refugia from

potential predators of turtles in the Northeast such as Procyon lotor Linnaeus

(Raccoon) and Lutra canadensis Schreber (River Otter) (Brooks et al. 1991,

Carroll and Ultsch 2006, Ernst et al. 1994).

Spotted Turtles in the island population showed sexual size dimorphism

in some traits but not others. Previous studies have reported differing results

with respect to the direction and degree of sexual size dimorphism in Spotted

Turtles. Ernst (1976) and Haxton (1998) reported no size differences

between the sexes, others reported that males had larger carapace lengths

(Litzgus et al. 2004), while others reported that females had larger plastron

lengths with no difference in carapace lengths (Litzgus 1996, Litzgus and

Mousseau 2004b). Sexual size dimorphism was evident in our population

with respect to carapace length and contour carapace length, with males being

the larger sex, and females having greater carapace heights. The greater

carapace height in females is likely related to maximizing body volume to

in turn maximize clutch size in a seasonal environment where brief and cool

summers prevent high clutch frequencies (Iverson et al. 1993, 1997; Litzgus

and Mousseau 2006). However, the small number of adult males captured

(n = 6) inhibits drawing any concrete conclusions.

Island females were smaller than mainland females in all traits measured.

The differences in adult body size between the two populations are likely to

be biologically relevant as they were readily apparent using the naked eye.

These results are surprising due to the close proximity of the two popula2008

D.J. Reeves and J.D. Litzgus 425

tions; body size variation among conspecific populations is usually observed

among widely separated populations and is attributed to climatic differences

among regions (Bergmann 1847, Mayr 1956, McNab 1971, Scholander

1955). Our findings suggest that the island population is reproductively isolated

from the mainland population. There is a positive relationship between

female body size and clutch frequency, and between female body size and

clutch size in the mainland population (Litzgus and Brooks 1998b) making

it logical to assume that there would be a selective advantage for larger

body size in females in the island population as well, since it is also at the

northern extreme of the Spotted Turtle’s distribution. Such a trend has also

been suggested in previous research on northern populations of small-bodied

turtles (Galbraith et al. 1989, Iverson et al. 1993, Litzgus and Brooks 1998b,

Murphy 1985). However, since the island females are smaller than mainland

females, there may be some evolutionary advantage to having a smaller body

size on the island. Other small-bodied turtle species, such as Emydura krefftii

Gray (Fraser Island Short-necked River Turtle), also exhibit dwarfism on

islands (Georges 1982). Island area may also influence body size (Maurer et

al. 1992); a smaller island, such as our study site, may have fewer resources,

driving animals on islands to be smaller, thus reducing the amount of total

resources they need to survive. However, given the long generation time

(≈25 years; Litzgus 2004) and great potential longevity of Spotted Turtles

(110 years for females; Litzgus 2006), it is unlikely that the island turtles

have had enough time to evolve smaller body sizes in response to limited

resources or some other environmental factor, making it likely that the unusually

small body sizes observed are due in large part to founder effects.

Future work should focus on surveying other islands suitable for Spotted

Turtles in the area. Primary productivity and turtle diets at the mainland and

island sites should also be investigated. In addition, genetic studies would

provide a glimpse into the evolutionary history of the island population and

could suggest if, and for how long, this population has been reproductively

isolated from mainland populations.

The estimated size of the adult Spotted Turtle population at the island

site was 31 individuals, and the actual number of adult turtles captured was

29. The number of new captures declined with each sampling visit, thus it

is possible that our surveys resulted in capturing 94% of the adult turtles

on the island, suggesting that the population size estimate was accurate and

that the population size estimator used was appropriate. In addition, we met

the assumptions of the Schnabel Mt model. The first assumption is that the

population is closed; our data do not violate this assumption as it is unlikely

that turtles could traverse the deep open water surrounding the island. The

island is separated from the mainland by a minimum of 900 m of open water

and a well-traveled boating waterway that is often choppy. There are also no

known Spotted Turtle populations on any islands within 1 km of the study

site, making it unlikely that a small-bodied turtle species would have access

to other populations. The second assumption is equal catchability. Because

426 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 3

juveniles are known to be more secretive and potentially occupy different

habitats than adults (Chippendale 1984, Ernst 1976), they were not used in

the population size estimate. Although the adult sex ratio was 1 male: 3.83

females, we do not feel that we violated the equal catchability assumption

as our sampling efforts suggest that the female-biased sex ratio is real (see

above). The third assumption, that marks are not lost, gained, or overlooked

was not violated because we used a widely accepted and tested method for

marking turtles (Cagle 1939), with the same researcher (D.J. Reeves) being

present at each of the sampling events.

The density of adult Spotted Turtles was 1.7 turtles/ha across the entire

island and 21.4 turtles/ha in a medium-sized wetland found on the island.

Spotted Turtles are known to aggregate in small wetlands to breed in spring

(Ernst 1967, 1970; Litzgus and Brooks 2000; Millam and Melvin 2001; Perillo

1997). The medium-sized wetland was the only open-canopy, permanent

wetland on the island and is likely used as a breeding aggregation site for

the population. Adult population density across the entire island was similar

to adult population densities at the extremes of the species’ range, but

was lower than in populations at the central portion of the range (Table 4).

Reported population densities could be influenced by a variety of variables:

variation in sampling intensity, latitudinal clines or habitat suitability, and

reproductive success (Litzgus and Mousseau 2004b). It is unlikely that sampling

efforts biased our population densities because the island was small

and thus easy for researchers to survey for turtles. In addition, Litzgus and

Mousseau (2004b) reported that while Spotted Turtle densities were highly

variable among populations at different latitudes, there was no significant relationship

between density and latitude. This result suggests that the habitat

suitability of the site and the reproductive success of the island population

are the primary causes of the relatively low population density.

Spotted Turtles at the island site were often found in small rock pools.

This behavior was unusual, and in fact, in the 16 years that J.D. Litzgus

has been conducting field work on Spotted Turtles in other locations, she

has never before observed turtles using rock pools. The pools were generally

devoid of emergent vegetation and thus provided little cover for turtles; we

therefore suspect that this unusual habitat use is related to thermoregulation

and/or feeding. The rock pools are small and shallow and would therefore

heat up quickly so that turtles within them could maintain relatively warm

body temperatures while not being exposed, as would be the case when

aerially basking. In addition, the pools are likely used by invertebrates for

breeding, thus providing a food source for turtles. Future work should focus

on measuring temperature and food availability in the rock pools.

Our study, although preliminary, provides new natural history and demographic

information on an island population of Spotted Turtles at the

northern extreme of the species’ range. Given that this is a previously unstudied

population, there are likely other currently unknown populations on

other suitable small isolated islands in the area, increasing the importance of

2008 D.J. Reeves and J.D. Litzgus 427

field surveys along the coastal regions of eastern Georgian Bay, ON where

there is an abundance of such islands. Our study also gives information

that may be useful for the design of a management plan for a species that is

declining across its range, with emphasis on isolated populations and populations

at geographic extremes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for the research came from Natural Sciences and Engineering

Research Council (NSERC), the Endangered Species Recovery Fund of the

World Wildlife Fund Canada and Environment Canada, the Ontario Ministry of

Natural Resources Species at Risk Fund, the Canada-Ontario Agreement, and

Laurentian University. The study was carried out under the guidelines of the

Canadian Council on Animal Care and the Laurentian University Animal Care

Committee (AUP# 2004-11-01). Field assistance was provided by R. Jones, S.

Gray, and J. Enneson. J. Crowley provided comments on an earlier draft of the

manuscript. Special thanks goes to Ron Black, Jake Rouse, and the Parry Sound

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). This study would not have been

possible without the support of local island residents who allowed us access to

their property and provided gracious support; they have requested to remain anonymous

to protect the location of the population so that future generations may

enjoy observing this federally endangered species.

Literature Cited

Barnwell, M.E., P.A. Meylan, and T. Walsh. 1997. The Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata)

in central Florida. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 2:405–408.

Bergmann, C. 1847. Über die Verhältnisse der Wärmeökonomie der tiere zu ihrer

Grösse. Göttinger Studien. Göttingen 3:595–708.

Braun, C.E. 2005. Techniques for Wildlife Investigations and Management. The

Wildlife Society, Baltimore, MD.

Brooks, R.J., G.P. Brown, and D.A. Galbraith. 1991. Effects of a sudden increase

in natural mortality of adults on a population of the Common Snapping Turtle

(Chelydra serpentina). Canadian Journal of Zoology 69:1314–1320.

Cagle, F.R. 1939. A system of marking turtles for future identification. Copeia

1939:170–172.

Carroll, D.M., and G.R. Ultsch. 2006. Glyptemys insculpta (Wood Turtle) predation.

Herpetological Review 37:215–216.

Chambers, B.A., B.J. Naylor, J. Nieppola, B. Merchant, and P. Uhlig 1997. Field

Guide to Forest Ecosystems of Central Ontario. SCSS Field Guide FG-01.

Queen’s Printer for Ontario, ON, Canada.

Chippindale, P.T. 1984. A Study of the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) in the Mer

Bleue Bog. Conservation Studies Publication No. 25, National Capitol Commission,

Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Chippindale, P.T. 1989. Courtship and nesting records for Spotted Turtles, Clemmys

guttata, in the Mer Bleue Bog, southeastern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist

103:289–291.

Cook, F.R., J.D. Lafontaine, S. Black, L. Luciuk, and R.V. Lindsay. 1980. Spotted

Turtles (Clemmys guttata) in eastern Ontario and adjacent Quebec. Canadian

Field-Naturalist 94:411–415.

Ernst, C.H. 1967. A mating aggregation of the turtle Clemmys guttata. Copeia

428 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 3

1967:473–474.

Ernst, C.H. 1970. Reproduction in Clemmys guttata. Herpetologica 26:228–232.

Ernst, C.H. 1976. Ecology of the Spotted Turtle, Clemmys guttata, (Reptilia,

Testudines, Testudinidae) in southeastern Pennsylvania. Journal of Herpetology

10:25–33.

Ernst, C.H., and R.W. Barbour. 1972. Turtles of the United States. University Press

Kentucky, Lexington, KY.

Ernst, C.H., J.E. Lovich and R.W. Barbour. 1994. Turtles of the United States and

Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Ewert, M.A., and C.E. Nelson. 1991. Sex determination in turtles: Diverse patterns

and some possible adaptive values. Copeia 1991:50–69.

Galbraith, D.A., R.J. Brooks, and M.E. Obbard. 1989. The influence of growth rate

on age and body size at maturity in female Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina).

Copeia 1989:896–904.

Georges, A. 1982. Diet of the Australian freshwater turtle Emydura krefftii (Chelonia:

Chelidae). Copeia 1982:331–336.

Graham, T.E. 1995. Habitat use and population parameters of the Spotted Turtle,

Clemmys guttata, a species of special concern in Massachusetts. Chelonian Conservation

and Biology 1:207–214.

Harding, J.H. 1985. Clemmys insculpta. Predation-mutilation. Herpetelogical Review

16:30.

Harding, J.H., and T.J. Bloomer. 1979. The Wood Turtle, Clemmys insculpta: A natural

history. Bulletin of the New York Herpetological Society 15:9–26.

Haxton, T.J. 1998. Home range and habitat selectivity of Spotted Turtles (Clemmys

guttata) in central Ontario: Implications for a management strategy. M.Sc. Thesis.

Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada.

Haxton, T.J., and M. Berrill. 1999. Habitat selectivity of Clemmys guttata in central

Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 77:593–599.

Hines, J.E. 1998. CAPTURE2 Software to compute population size for closed populations

from mark-recapture data. USGS-PWRC. Available online at http://www.

mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/software/specrich.html. Accessed February 2007.

Iverson, J.B., C.P. Balgooyen, K.K. Byrd, and K.K. Lyddan. 1993. Latitudinal

variation in egg and clutch size in turtles. Canadian Journal of Zoology 71:2448–

2461.

Iverson, J.B., H. Higgins, A.S. Sirulnik, and C. Griffiths. 1997. Local and geographic

variation in the reproductive biology of the Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina).

Herpetologica 53:96–117.

Kaufmann, J.H. 1992. The social behavior of Wood Turtles (Clemmys insculpta) in

central Pennsylvania. Herpetological Monographs 6:1–25.

Litzgus, J.D. 1996. Life history and demography of a northern population of

Spotted Turtles, Clemmys guttata. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Guelph, Guelph,

ON, Canada.

Litzgus, J.D. 2004. Status report on the Spotted Turtle, Clemmys guttata. Committee

on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Environment

Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Litzgus, J.D. 2006. Sex differences in longevity in the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata).

Copeia 2006:281–288.

Litzgus, J.D., and R.J. Brooks. 1998a. Reproduction in a northern population of

2008 D.J. Reeves and J.D. Litzgus 429

Clemmys guttata. Journal of Herpetology 34:178–185.

Litzgus, J.D., and R J. Brooks. 1998b. Growth in a cold environment: Body size and

sexual maturity in a northern population of Spotted Turtles, Clemmys guttata.

Canadian Journal of Zoology 77:1348–1357.

Litzgus, J.D., and R.J. Brooks. 2000. Habitat and temperature selection of Clemmys

guttata from a northern population. Journal of Herpetology 34:178–185.

Litzgus, J.D., and T.A. Mousseau. 2004a. Home range and seasonal activity of southern

Spotted Turtles (Clemmys guttata): Implications for management. Copeia

2004:804–817.

Litzgus, J.D., and T.A. Mousseau. 2004b. Demography of a southern population of

the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata). Southeastern Naturalist 3:391–400.

Litzgus, J.D., and T.A. Mousseau. 2006. Geographic variation in reproduction in a

freshwater turtle (Clemmys guttata). Herpetologica 62:132–140.

Litzgus, J.D., J.P. Costanzo, R.J. Brooks, and R.E. Lee, Jr. 1999. Phenology and ecology

of hibernation in Spotted Turtles (Clemmys guttata) near their northern range

limit. Canadian Journal of Zoology 77:1348–1357.

Litzgus, J.D., S.E. DuRant, and T.A. Mousseau. 2004. Clinal variation in body and

cell size in a widely distributed vertebrate ectotherm. Oecologia 140:551–558.

Lovich, J.E. 1989. The Spotted Turtles of Cedar Bog: Historical analysis of a declining

population. Pp. 23–28, In R.C. Glotzhober, A. Kochman, and W.T. Schultz

(Eds.). Proceedings of Cedar Bog Symposium II. Ohio Historical Society, Columbus,

OH.

Lovich, J.E., and T.R. Jaworski. 1988. Annotated check list of amphibians and reptiles

reported from Cedar Bog, Ohio. Ohio Journal of Science 88:139–143.

Mauger, D. 1990. A resurvey of the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) population at

Lockport Prairie Nature Preserve, Will County, Illinois. Unpublished report. Forest

Preserve District of Will County, Joliet, IL. 11 pp.

Mauger, D. 2004. Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) survey at Lockport Prairie Nature

Preserve, spring-summer 2004. Unpublished report. Forest Preserve District

of Will County, Joliet, IL.. 33 pp.

Maurer, B.A., J.H. Brown, and R.D. Rusler. 1992. The micro and macro of body-size

evolution. Evolution 46:939–953.

Mayr, E. 1956. Geographical character gradients and climactic adaptation. Evolution

10:105–108.

McGee, E., E.O. Moll, and D. Mauger. 1989. Baseline survey of a Spotted Turtle

(Clemmys guttata) population at Romeoville prairie nature preserve, Will County,

Illinois. Unpublished report. Forest Preserve District of Will County, Joliet,

IL. 12 pp.

McNab, B.K. 1971. On the ecological significance of Bergmann’s rule. Ecology

52:845–854.

Millam, J.C., and S.M. Melvin. 2001. Density, habitat use, and conservation of

Spotted Turtles (Clemmys guttata) in Massachusetts. Journal of Herpetology

35:418–427.

Morreale, S.J., J.W. Gibbons, and J.D. Congdon. 1984. Significance of activity and

movements in the Yellow-bellied Slider Turtle (Pseudemys scripta). Canadian

Journal of Zoology 62:1038–1042.

Murphy, E.C. 1985. Bergmann’s rule, seasonality, and geographic variation in body

430 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 3

size of House Sparrows. Evolution 39:1327–1334.

Perillo, K.M. 1997. Seasonal movements and habitat preferences of Spotted Turtles

(Clemmys guttata) in north central Connecticut: Linnaeus Fund Research Report.

Chelonian Conservation and Biology 2:445–447.

Roff, D.A. 1992. The Evolution of Life Histories. Chapman and Hall, New

York, NY.

Schnabel, Z.E. 1938. The estimation of the total fish population of a lake. American

Mathematical Monthly 45:348–352.

Scholander, P. F. 1955. Evolution of climactic adaptation in homeotherms. Evolution

9:15–26.

Seburn, D.C. 2003. Population structure, growth, and age estimation of Spotted

Turtles, Clemmys guttata, near their northern limit: An 18-year follow-up. Canadian

Field-Naturalist 117:436–439.

Stearns, S.C. 1976. Life-history tactics: A review of the ideas. The Quarterly Review

of Biology 51:3–47.

Walde, A.D., R.J. Bider, C. Daigle, D. Masse, J. Bourgeois, J. Jutras, and R.D. Titman.

2003. Ecological aspects of a Wood Turtle, Glyptemys insculpta, population

at the northern limited of its range in Quebec. Canadian Field-Naturalist

117:377–388.

Wilson, T.P. 1994. Ecology of the Spotted Turtle, Clemmys guttata, at the western

range limit. M.Sc. Thesis. Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL.