2008 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 15(4):595–606

The Appalachian Inferno: Historical Causes for the

Disjunct Distribution of Plethodon nettingi

(Cheat Mountain Salamander)

Thomas K. Pauley*

Abstract - The original Picea rubens (Red Spruce) forest in West Virginia covered

approximately 1.5 million acres, most of which was eliminated between 1870 and

1920 by clear-cutting and conflagrations. The total range of Plethodon nettingi (Cheat

Mountain Salamander) was confined within this Red Spruce forest. Fires burned the

duff and soil to the bedrock in many places, thus eliminating salamander habitats. It

is hypothesized that Cheat Mountain Salamanders were eradicated throughout much

of their range, and only areas with large emergent rocks or boulder fields provided

refugia where they survived.

Introduction

Prior to arrival of European lumber crews in the mid- to late 1800s, the

high elevations of the Allegheny Mountains in eastern West Virginia were

covered with approximately 1.5 million acres of majestic Picea rubens

Sarg. (Red Spruce) forest. By 1900, the forest had been reduced to 225,000

acres (West Virginia Conservation Commission 1908). This near elimination

of the Red Spruce forest has been attributed to improved technologies

for cutting, hauling, and manufacturing timber (Lewis 1998). Stickel (1923)

summed up destruction of the original forest by stating that lumbermen followed

a policy of “cut clean and then clear out” (from Lewis 1998).

Before large-scale lumbering activities began, accidental wildfires and

“hacking” (a technique used to remove trees by girdling with a hatchet or

an axe) had destroyed the original forest in some locations. A few years

later, after the trees had died, farmers would return to the area and burn the

dead trees and undergrowth in order to clear the land for grazing. Hacking

was practiced prior to the Civil War in the Red Spruce areas of eastern and

southern portions of Randolph and northern Pocahontas counties (Clarkson

1964, Hopkins 1908).

Possibly the first major destructive fire in the original forest occurred in

1863 when fire escaped from a campfire of Confederate scouts on the Roaring

Plains section of Dolly Sods in Randolph County. This fire burned the

summit and sides of the Allegheny Mountains from Tucker County through

Grant, Pendleton, and Randolph counties to the head waters of the Greenbrier

River (West Virginia Conservation Commission 1908). These events

were the beginning of what would lead to the destruction of the original

*Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755;

pauley@marshall.edu.

596 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 4

Red Spruce forest, the habitat of the federally protected Plethodon nettingi

(Green) (Cheat Mountain Salamander).

I have studied the Cheat Mountain Salamander, an eastern, small

woodland salamander, for 30 years and have found about 80 disjunct

populations in an area that extends approximately 92 km north to south and

31 km east to west encompassed within five counties in the high Alleghenies

of eastern West Virginia (Pauley 2007). Their habitat typically consists of

forests dominated by Red Spruce and Betula alleghaniensis Britt. (Yellow

Birch), where the forest floor is covered with Bazzania trilobata (L.) S.

Gray (Threelobed Bazzania, a liverwort). Such habitats are associated with

emergent rocks, boulder fields, or narrow ravines lined with Rhododendron

maximum L. (Great Rhododendron) (Pauley 2005).

Clearcuts, such as those that occurred in the high elevations of eastern

West Virginia in the late 1800s, are detrimental to forest salamander

populations (Ash 1988, Mitchell et al. 1996, Petranka et al. 1993, Sattler

and Reichenbach 1998). Clear-cutting opens the forest floor to the drying

effects of sun and wind resulting in a dry humus or litter layer that

provides fuel for wildfires. In the once abundant Red Spruce forests in

eastern West Virginia, leaf-litter decay was slow due to the acidic nature

of spruce needles, which resulted in the formation of a thick layer of partially

decayed needles and twigs several feet deep (Brooks 1911). Most

fires that occurred in the clearcut areas of the original forest were started

by sparks from Shay locomotives, sawmills, campfires, and the careless

disposal of hot ashes from fireboxes of tenders (Fansler 1962, West Virginia

Conservation Commission Report 1908). With the highly combustible

properties of dry spruce needles, fires started quickly, and the extreme

heat likely reached deep into the rock layers beneath the soil where salamanders

took refuge. Because forest fires tend to draw enormous amounts

of oxygen from both above and below the surface of the ground (Michael

2002), many species of salamanders may have died due to lack of oxygen

before the heat reached their refuge.

A thick, moist litter layer on the forest floor is essential to maintain

healthy woodland salamander populations (Ash 1997). Moist litter

is used as the main foraging venue of woodland salamanders (Jaeger

1978, 1980), as refugia for all age classes, and for cutaneous respiration

(Ash 1995). Nests of several species of woodland salamanders, including

Cheat Mountain Salamanders, are associated with leaf litter where

they are found in and under logs, under bark on logs, and under surface

rocks (Green and Pauley 1987). Clearcuts and fires can destroy this layer

and make such disturbed areas inhospitable for forest salamanders. The

purpose of this paper is to suggest a hypothesis for the link between the

fragmented distribution of the Cheat Mountain Salamander, a threatened

endemic (Federal Register 1989) woodland salamander, and historical disturbance

and destruction of the high-elevation forests due to clearcutting

2008 T.K. Pauley 597

and subsequent fires that occurred from 1870 through 1960 in eastern

West Virginia.

Methods

Salamander surveys were conducted during daylight hours from May

1976 to October 2006 and involved turning cover objects such as rocks and

logs. In most cases, I only searched within 48-h following a rain event. Data

recorded included species, size class (i.e., juvenile, subadult, adult), gender,

cover object, and general habitat characteristics including dominant plant

species and presence of emergent rocks or boulder fields. I searched in numerous

sites in each of four study areas. If multiple sites with Cheat Mountain

Salamanders were within the typical home-range size of Plethodon

cinereus (Green) (Eastern Red-backed Salamander) (Kleeberger and Werner

1982), a species similar in size to the Cheat Mountain Salamander, I considered

these multiple Cheat Mountain Salamander sites to be one population.

If sites were farther apart than could be contained in the typical home range

of the Eastern Red-backed Salamander, I considered them separate Cheat

Mountain Salamander populations.

In this paper, I present species richness and abundance in four areas within

the geographic range of the Cheat Mountain Salamander that were impacted

by clearcuts and fires. Because the Cheat Mountain Salamander is a federally

protected species, exact locations of populations are not provided.

Results and Discussion

During the 30 years of this study, I searched about 1300 sites and examined

22,389 forest-dwelling salamanders throughout the entire range

of the Cheat Mountain Salamander (Table 1). Of these, only about 10.0%

were Cheat Mountain Salamanders, found at approximately 80 disjunct

locations. In 1996, a colleague and I conducted detailed inventories where

Table 1. Salamander species and numbers observed from 1976 through 2006 throughout the

range of the Cheat Mountain Salamander.

Species Number observed

Desmognathus ochrophaeus (Allegheny Mountain Dusky Salamander) 7110

Eurycea bislineata (Green) (Northern Two-lined Salamander) 95

Gyrinophilus p. porphyriticus (Green) (Northern Spring Salamander) 41

Hemidactylium scutatum (Temminck and Schlegel in Von Siebold) 77

(Four-toed Salamander)

Plethodon cinereus (Eastern Red-backed Salamander) 9880

Plethodon glutinosus (Northern Slimy Salamander) 987

Plethodon nettingi (Cheat Mountain Salamander) 2229

Plethodon wehrlei (Wehrle’s Salamander) 1746

Notophthalmus v. viridescens (Red-spotted Newt) 224

Total 22,389

598 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 4

I had observed one population of Cheat Mountain Salamanders 25 years

earlier during a less extensive search. We found that Cheat Mountain

Salamanders were actually in 12 disjunct sites that were all on or adjacent

to emergent rocks.

After reviewing habitat characteristics of the 60 known populations

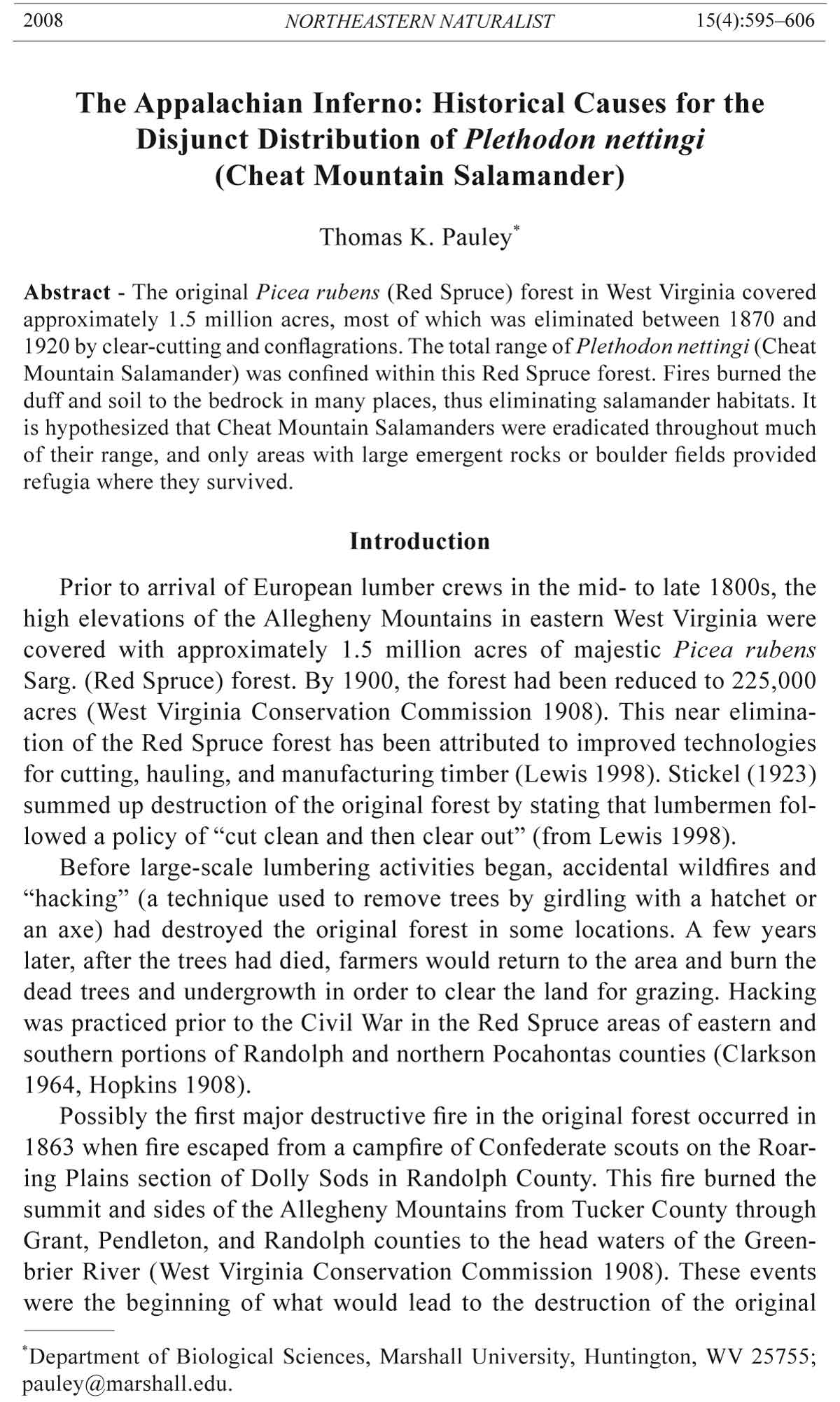

for Cheat Mountain Salamanders at that time (1996), at least 86.7% (n =

52) were associated with emergent rocks or small boulder fields (Fig. 1).

Rocks may have been associated with some or all of the remaining eight

populations; however, because in the earlier years of my work I did not

understand the positive association between rocks and the occurrence of

Cheat Mountain Salamanders, I did not record the presence or absence of

these structures.

From historical accounts, forest stands supporting all but one of the approximately

80 known populations (Gaudineer Scenic Area) have been cut

since 1870 and, in most cases, clearcut. Historical records show that many

isolated Cheat Mountain Salamander populations associated with emergent

rocks and boulder fields today, existed in areas that were clearcut and burned

between 1870 and 1960. Here, I describe four areas as examples where Cheat

Mountain Salamanders are confined to microhabitats where forests were

burned during the initial cutting of the virgin forests. These areas include:

Spruce Knob (Pendleton County), Blackwater Canyon (Tucker County),

Dolly Sods (Grant and Tucker counties), and Bald Knob (Pocahontas County)

(Fig. 2).

Spruce Knob (Pendleton County)

Spruce Knob (Pendleton County), the highest elevation in West Virginia,

is perhaps the epitome of what the devastation must have been like during

the logging of the virgin forest and the subsequent burning of the litter and

soil. The 1899–1900 biennial report to the State Board of Agriculture stated

that clear-cutting methods employed by timbering companies removed trees

of all sizes at a rate of 30 to 50 acres per day, which left Spruce Knob a desolate

place (West Virginia Conservation Commission 1908). Stickel (1923)

acknowledged that after the initial logging in the Spruce Knob area there

was not a single tree left standing and the area was one of the best examples

of wasteful and destructive logging (From Lewis 1998).

A.B. Brooks, the state’s leading conservationist and Director of the

West Virginia Geological Survey in the early 1900s, described the duff

of the original forest as a collection of spruce needles, leaves, mosses,

and lichens that decomposed over centuries to form a layer of soil one to

three feet thick. This highly flammable, dry organic matter was exposed

to sunlight due to removal of the trees and was subject to ignition by the

slightest spark. According to an eyewitness, the most formidable fire in

the Spruce Knob area swept the eastern side of the Allegheny Mountains

around the headwaters of Big Run in Pendleton County located just west

2008 T.K. Pauley 599

Figure 1. Examples of an emergent rock and boulder field where Plethodon nettingi

(Cheat Mountain Salamander) may have survived forest clearcuts and fires and where

they frequently occur today.

600 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 4

of Spruce Knob. Flames were reported to exceed the tallest “pines” (Red

Spruce) and advanced 10 miles an hour. Brooks (1911) concluded that

perhaps 1000 years would not be enough time to replace the humus of the

soil that fire had destroyed.

After clearcuts and several fires in the Spruce Knob area, F.E. Brooks

visited the region and reported that forests were found east of the Allegheny

Front at Spruce Knob and into Virginia where fires had not occurred,

but to the west, most of the countryside was a wasteland of Pteridium

aquilinum (L.) Kuhn (Bracken Fern) that covered the ground from which

almost every trace of the original forest had been destroyed by fires

(Brooks 1908).

The disjunct microdistribution of Cheat Mountain Salamanders in

the Spruce Knob area today attests to the near obliteration of the original

forest by fires. Nearly 100 years after the fires, I surveyed 58 sites

Figure 2. Range of

Plethodon nettingi

(Cheat Mountain

Salamander) with

burn sites.

2008 T.K. Pauley 601

in suitable Cheat Mountain Salamander habitat (i.e., areas within a Red

Spruce and Yellow Birch forest stand) and found that they occurred in

only eight disjunct populations in the Spruce Knob area. These salamanders

were discovered in boulder fields on the upper slopes and on a ridge

that stretched from the highest elevational point northeast. Many of these

sites surveyed over 30 years were outside of the boulder field in the most

severely burned area, and no Cheat Mountain Salamanders have been

observed in these sites. Other species of salamanders such as Eastern

Red-Backed Salamanders, Plethodon wehrlei Fowler and Dunn (Wehrle’s

Salamander), P. glutinosus (Green) (Northern Slimy Salamander), Desmognathus

ochrophaeus Cope (Allegheny Mountain Dusky Salamander),

and Notophthalmus viridescens viridescens (Rafinesque) (Red-Spotted

Newt, Red Eft) were found throughout areas in and outside of boulder

fields and in areas devastated by fires (Table 1).

Blackwater Canyon (Tucker County)

One the most detailed chronologies is of a forest fire that occurred in

the Blackwater Canyon, 4.8 km north of Hendricks, Tucker County. Fansler

(1962), an eyewitness to the fire, described the conditions that led to this

destructive fire, “As long as the trees stood, the humus soil remained shaded

and damp and would not burn, but when the trees were cut the sun came in

and dried the soil to the highly combustible peat. When fires occurred, the

peat burned and smoldered for months and only a heavy and protracted snow

would extinguish it.” Fansler watched a fire start in the Blackwater Canyon

on 30 May 1914. He stated “The sky over Hendricks was lighted with the

reflection of the blaze to such an extent that one could sit on the platform of

Harvey’s store at midnight and read the afternoon paper without any other

illumination.” Snows finally extinguished the fire on 30 November 1914,

after burning six months. Prior to the 1914 fire, Fansler reported a fire that

burned 7000 acres on the north side of the Canyon in 1910 above the Western

Maryland Railway.

I searched 27 sites on the north side of the Canyon, which contains

habitat characteristic of Cheat Mountain Salamanders. Of these sites, I

found Cheat Mountain Salamanders in only three populations: one small

locality in a boulder field in the floodplain and two populations among

large emergent rocks along the rim of the Canyon. Species found in the

burned areas included Eastern Red-backed Salamander, Northern Slimy

Salamander, and Allegheny Mountain Dusky Salamander. In many locations

on the north side of the Canyon, the soil was thin and dry, and no

salamanders were discovered.

Dolly Sods (Tucker County and Grant County)

Dolly Sods was logged between the 1880s and the 1920s, and numerous

fires burned the slash and the centuries of accumulated humus. In July

1930, one fire destroyed 24,000 acres in the middle of the Sods (Turner

602 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 4

2001). Fires smoldered for months and burned the forest and ground cover

down to bare rock. Old charred stumps and charcoal fragments can be

still be found under the surface in places like Dobbins Slashings, which

is located west of Bear Rocks (Allard and Leonard 1952). Today, in many

locations, the Red Spruce forest has been replaced by hardwood tree species,

such as Acer rubrum L. (Red Maple) and Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.

(American Beech). Rocks that were once covered with 0.5 m or more of

humus are now exposed to sunlight, making the area uninhabitable for

woodland salamanders (Fig. 3).

The first recorded fire in the Dolly Sods region was in 1863 when a

campfire of Confederate scouts escaped and ignited the forest in the Roaring

Plains and Flat Rock Plains areas (West Virginia Conservation Commission

1908). Today, these areas consist of xeric habitat with numerous exposed

rocks. In this region of Dolly Sods, I have surveyed 10 sites since 1979.

Cheat Mountain Salamanders were found in one locality in a boulder field

along South Fork, a habitat that could have provided shelter for them during

the 1863 fire.

In addition to the surveys in the Roaring Plains and Flat Rock Plains areas,

I have conducted salamander inventories in 36 sites throughout the rest

of Dolly Sods. Many sites have been searched several times during the years,

and I have located Cheat Mountain Salamanders in only four sites between

Fisher Spring Run and Roaring Plains. This area consists of boulder fields

Figure 3. Rocks exposed after fires destroyed the humus and soil at Dobbins Slashings

near the Allegheny Front at Dolly Sods.

2008 T.K. Pauley 603

with ravines and sufficient soil deposits to support woodland salamanders.

The most intensely burned area was probably between Fisher Spring Run

and Mount Storm Lake. I surveyed 20 sites in this area and only found one

Eastern Red-backed Salamander.

Bald Knob (Pocahontas County)

Bald Knob was clearcut in 1902, leaving dry duff and dead spruce

tops and branches that burned in 1904. The area was cut again between

1950 and 1958 (Clarkson 1990), followed by a storm that felled a large

number of spruce trees during the winter of 1979–1980 (Clarkson 1990).

Brooks (1948) reported nests and adults of Cheat Mountain Salamanders

at Bald Knob in 1940. From 1979–1990, I searched 12 sites on and

around Bald Knob and found Cheat Mountain Salamanders in only one

site associated with emergent rocks on the west slope. The summit had a

new growth of Red Spruce with the liverwort Bazzania trilobata, but I did

not find Cheat Mountain Salamanders. Of the remaining 11 sites, I found

four Eastern Red-backed Salamanders in one site; no salamanders were

found in the other 10 sites. Some Cheat Mountain Salamanders may have

survived the initial cut and burn on Bald Knob, but succumbed to the subsequent

cuts in the 1950s and in 1979–1980.

Conclusions

Cheat Mountain Salamanders appear to be associated with either emergent

rocks or boulder fields. Cool moist spots under rocks serve as refugia

where salamanders may survive clearcuts and fires. All Cheat Mountain

Salamander populations observed since 1996 have been found in these rocky

microhabitats. Cheat Mountain Salamanders survived cutting and burning

of the original forest only around large rocks, boulder fields, and narrow

ravines protected by thick growths of Great Rhododendron. There are areas

with emergent rocks and boulder fields within the range of the Cheat Mountain

Salamander where the salamanders do not occur (Pauley 2007). Fires

in such areas may have been too severe for Cheat Mountain Salamanders to

survive in these relatively safe refugia.

Competition for moist spots with Allegheny Mountain Dusky Salamanders

and for food and nesting sites with Eastern Red-backed Salamanders

currently limits Cheat Mountain Salamanders to rocky microhabitats

(Green and Pauley 1987; B.A. Pauley 1998; T.K. Pauley 1980, 2005).

Adams et al. (2007) suggested that Eastern Red-backed Salamanders have

morphological and behavioral flexibility that may allow them to adapt

more quickly to local environmental conditions. This flexibility perhaps

gives Eastern Red-backed Salamanders the competitive advantage over

Cheat Mountain Salamanders in becoming re-established in a recovering

forest. Allegheny Mountain Dusky Salamanders, a species that deposits

eggs in stream banks and seeps rather than the terrestrial habitats where

604 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 4

Cheat Mountain Salamanders nests are located (Green and Pauley 1987,

Pauley et al. 2006), could survive in streams and seeps during cutting

events and fires, thus providing them a survival advantage. The broader

ranges of both Eastern Red-backed Salamanders and Allegheny Mountain

Dusky Salamanders suggest they are more capable of adapting to environmental

extremes than Cheat Mountain Salamanders.

Roads, ski slopes, hiking trails, rights-of-way, and developments currently

impact all known Cheat Mountain Salamander populations (Pauley

2005), by opening the forest floor and limiting Cheat Mountain Salamanders

to small, disjunct populations. Fortunately, some populations of Cheat

Mountain Salamanders described in this paper are within the boundaries of

the Monongahela National Forest and are protected from future logging and

developments.

Acknowledgments

I thank the many students who helped me with the field work during the last 30

years. Most were from Salem College and Marshall University. I acknowledge and

appreciate the financial support provided by the United States Forest Service, United

States Fish and Wildlife Service, and West Virginia Division of Natural Resources

that allowed me to conduct many of the original surveys. I thank Edwin Michael,

Ronald Lewis, Craig Stihler, Jessica Wooten, and Jayme Waldron for valuable comments

on the manuscript.

Literature Cited

Adams, D.C., M.E. West, and M.L. Collyer. 2007. Location-specific sympatric

morphological divergence as a possible response to species interactions in

West Virginia Plethodon salamander communities. Journal of Animal Ecology

76:289–295.

Allard, H.A., and E.C. Leonard. 1952. The Canaan and the Stony River Valleys of

West Virginia, their former magnificent spruce forests, their vegetation and floristics

today. Castanea 17:1–60.

Ash, A.N. 1988. Disappearance of salamanders from clearcut plots. Journal of the Elisha

Mitchell Science Society 104:116–122.

Ash, A.N. 1995. Effects of clear-cutting on litter parameters in the southern Blue

Ridge Mountains. Castanea 60:89–97.

Ash, A.N. 1997. Disappearance and return of plethodontid salamanders to clearcut

plots in the southern Blue Ridge Mountains. Conservation Biology 11(4):983–

989.

Brooks, A.B. 1911. West Virginia Geological Survey. Forestry and Wood Industries.

5:52–53.

Brooks, F.E. 1908. The top of West Virginia. The Illustrated Monthly West Virginian

(October–November) 3:11–18.

Brooks, M. 1948. Notes on the Cheat Mountain Salamander. Copeia 4:239–244.

Clarkson, R.B. 1964. Tumult on the Mountains: Lumbering in West Virginia, 1770–

1920. McClain Printing Company, Parsons, WV. 410 pp.

2008 T.K. Pauley 605

Clarkson, R.B. 1990. On Beyond Leatherbark: The Cass Saga. McClain Printing

Company, Parsons, WV. 625 pp.

Fansler, F.F. 1962. History of Tucker County, West Virginia. McClain Printing Company,

Parsons, WV. 737 pp.

Federal Register. 1989. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants: Determination

of threatened status for the Cheat Mountain Salamander and endangered

status for the Shenandoah Salamander. 54:34464–34486.

Green, N.B., and T.K. Pauley. 1987. Amphibians and Reptiles in West Virginia. First

Edition. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA. 241 pp.

Hopkins, A.D. 1908. The Spruce in West Virginia. Report of the West Virginia State

Board of Agriculture for quarter ending June 30, 1908. Charleston, WV.

Jaeger, R.G. 1978. Plant climbing by salamanders: Periodic availability of plantdwelling

prey. Copeia 1978:686–691.

Jaeger, R.G. 1980. Microhabitats of a terrestrial forest salamander. Copeia

1980:265–268.

Kleeberger, S.R., and J.K. Werner. 1982. Home range and homing behavior of

Plethodon cinereus in northern Michigan. Copeia 1982:409–415.

Lewis, R.L. 1998. Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation,

and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880–1920. The University of North

Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC. 348 pp.

Michael, E.D. 2002. A Valley Called Canaan: 1885–2002. McClain Printing Company,

Parsons, WV. 223 pp.

Mitchell, J.C., J.A. Wicknick, and C.D. Anthony. 1996. Effects of timber harvesting

practices on peaks of Otter Salamander (Plethodon hubrichti) populations. Amphibian

and Reptile Conservation 1:15–19.

Pauley, B.A. 1998. The use of emergent rocks and refugia for the Cheat Mountain

Salamander, Plethodon nettingi Green. M.Sc. Thesis. Marshall University, Huntington,

WV. 81 pp.

Pauley, T.K. 1980. The ecological status of the Cheat Mountain Salamander.

United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Elkins, WV. Report

7798. 160 pp.

Pauley, T.K. 2005. Reflections upon amphibian conservation. Pp. 277–281, In M.J.

Lannoo (Eds.). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of the United

States Species. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Pauley, T.K. 2007. Revised notes on the range of the Cheat Mountain Salamander,

Plethodon nettingi (Amphibia: Caudata). Proceedings of the West Virginia Academy

of Science 79(2):16–21.

Pauley, T.K., M.B. Watson, J.N. Kochenderfer, and M. Little. 2006. Response of

Salamanders to Experimental Acidification Treatments. Pp. 189–206, In M.B.

Adams, D.R. DeWalle, and J.L. Hom (Eds.). The Fernow Watershed Acidification

Study Series: Environmental Pollution. Springer Publishers, Dodrecht,

The Netherlands.

Petranka, J.W., Eldridge, M.E., and E. Haley. 1993. Effects of timber harvesting on

southern Appalachian salamanders. Conservation Biology 7:362–370.

Sattler, P., and N. Reichenbach. 1998. The effects of timbering on Plethodon

hubrichti: Short-term effects. Journal of Herpetology 32:399–404.

606 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 4

Stickel, P.W. 1923. Logging in the mountains of West Virginia. A report of the study

of lumber operations of the Horton, West Virginia, sawmill of Parsons Pulp and

Paper Company. Report submitted for completion of Forest Utilization 5, New

York State College of Forestry, Syracuse, NY.

Turner, J. 2001. Recovered wilderness: Solitude and human history intertwine in the

Dolly Sods. The Magazine of the Sierra Club September/October:30–32.

West Virginia Conservation Commission. 1908. West Virginia Board of Agriculture,

biennial report, 1899 and 1900. The Tribune Printing Co., Charleston, WV.