A Population Crash of the Red-backed Vole (Myodes gapperi)

in Nova Scotia Inferred from Bycatch of the Long-tailed Shrew

(Sorex dispar)

Aaron B.A. Shafer and Donald T. Stewart

Northeastern Naturalist, Volume 15, Issue 4 (2008): 626–629

Full-text pdf (Accessible only to subscribers.To subscribe click here.)

Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Current Issue: Vol. 30 (3)

Check out NENA's latest Monograph:

Monograph 22

Vol. 15, No. 4

A Population Crash of the Red-backed Vole (Myodes gapperi)

in Nova Scotia Inferred from Bycatch of the Long-tailed Shrew

(Sorex dispar)

Aaron B.A. Shafer1,2,* and Donald T. Stewart2

Abstract - In 2006, we collected two Sorex dispar (Long-tailed Shrew) specimens from Mac-

Donald Pond, NS, Canada, which is a range extension of this elusive species. Trapping data

revealed significantly lower numbers of Myodes (= Clethrionomys) gapperi (Red-backed Vole)

bycatch than expected based on previous studies. Red-backed Voles are the most common rodent

found in Nova Scotia forests. Here we report an apparent population crash of Red-backed

Voles in Nova Scotia, along with a closer examination of a Cape Breton Island population.

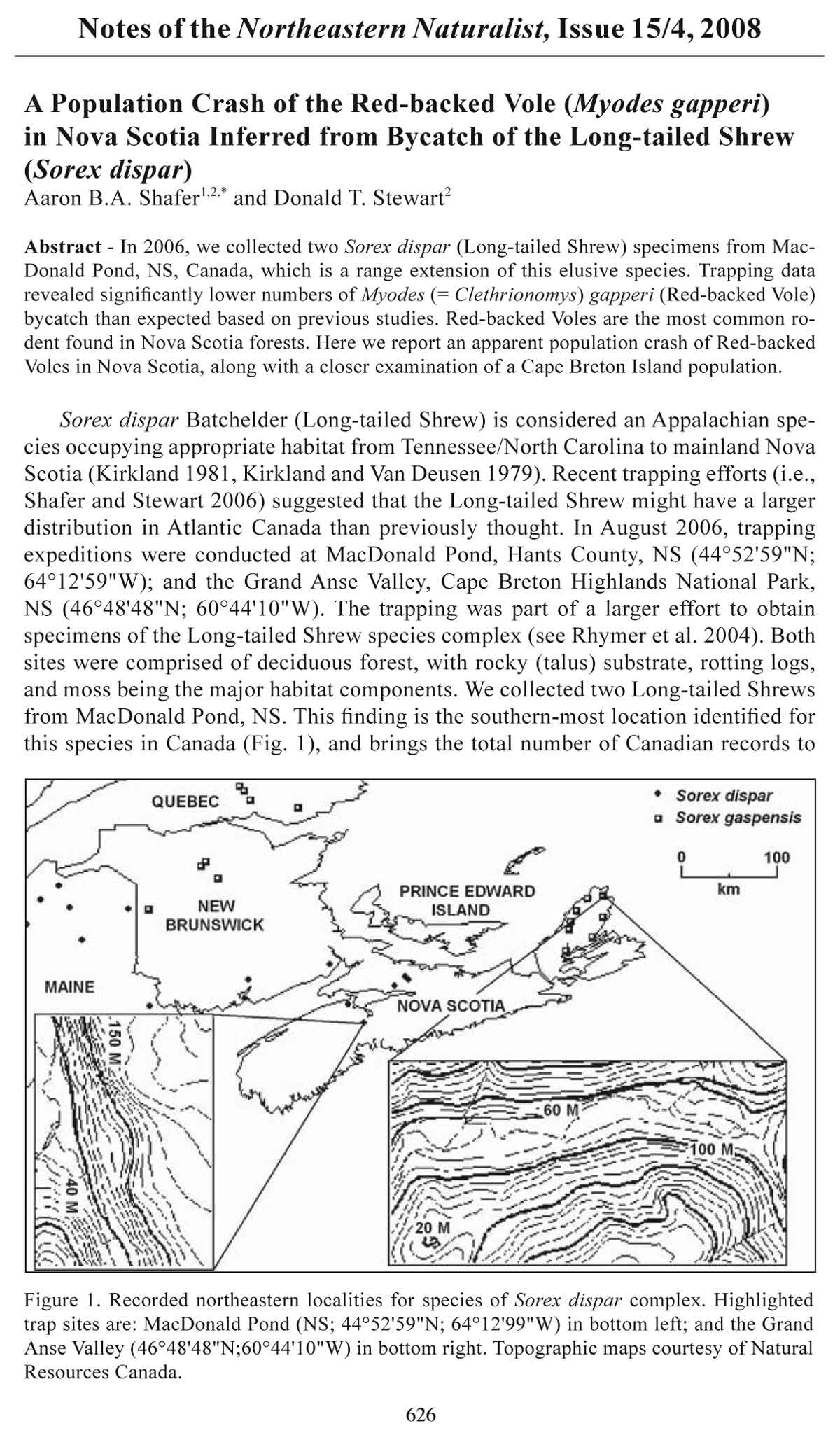

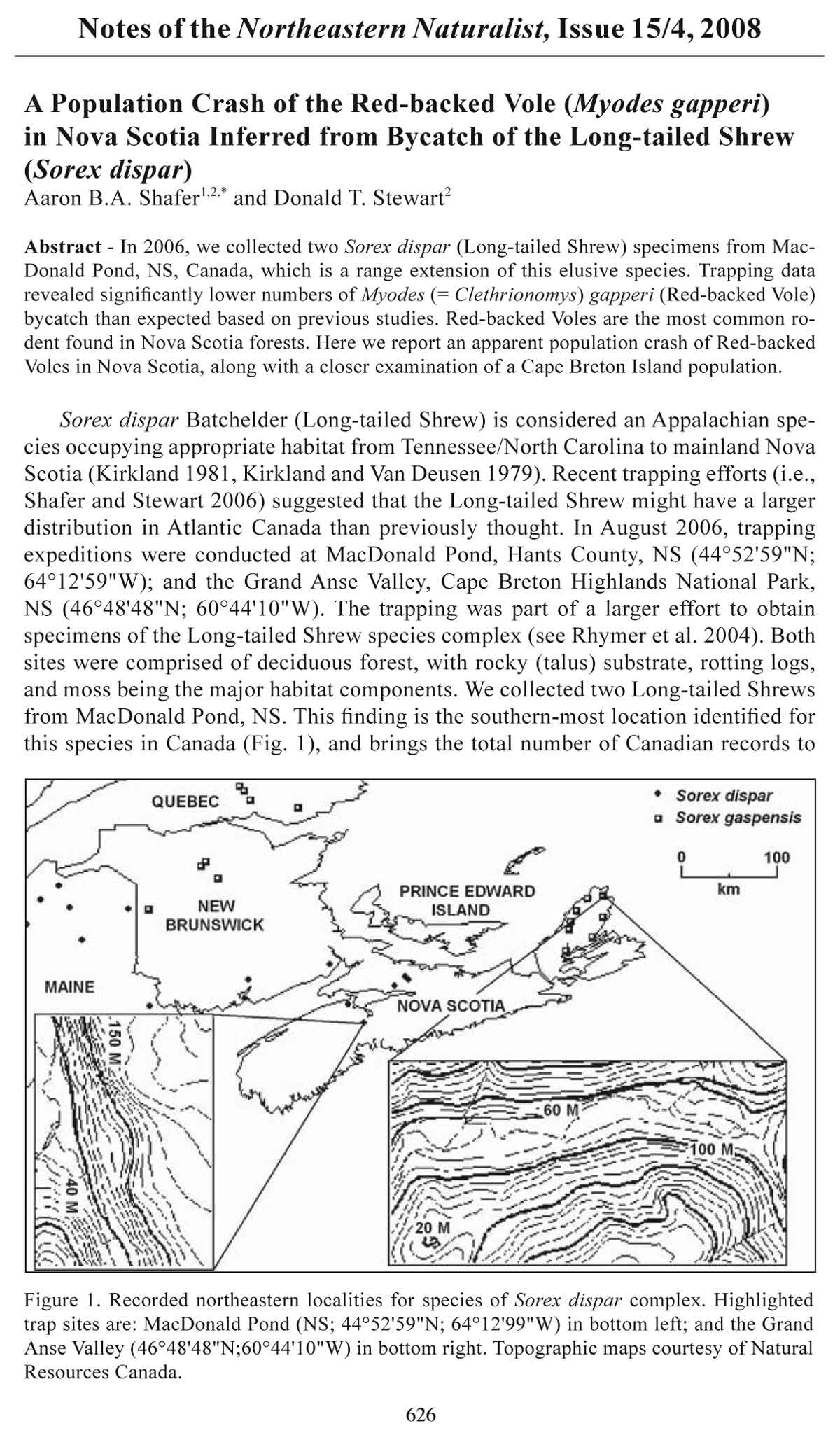

Sorex dispar Batchelder (Long-tailed Shrew) is considered an Appalachian species

occupying appropriate habitat from Tennessee/North Carolina to mainland Nova

Scotia (Kirkland 1981, Kirkland and Van Deusen 1979). Recent trapping efforts (i.e.,

Shafer and Stewart 2006) suggested that the Long-tailed Shrew might have a larger

distribution in Atlantic Canada than previously thought. In August 2006, trapping

expeditions were conducted at MacDonald Pond, Hants County, NS (44°52'59"N;

64°12'59"W); and the Grand Anse Valley, Cape Breton Highlands National Park,

NS (46°48'48"N; 60°44'10"W). The trapping was part of a larger effort to obtain

specimens of the Long-tailed Shrew species complex (see Rhymer et al. 2004). Both

sites were comprised of deciduous forest, with rocky (talus) substrate, rotting logs,

and moss being the major habitat components. We collected two Long-tailed Shrews

from MacDonald Pond, NS. This finding is the southern-most location identified for

this species in Canada (Fig. 1), and brings the total number of Canadian records to

Notes of the Northeastern Nat u ral ist, Issue 15/4, 2008

626

Figure 1. Recorded northeastern localities for species of Sorex dispar complex. Highlighted

trap sites are: MacDonald Pond (NS; 44°52'59"N; 64°12'99"W) in bottom left; and the Grand

Anse Valley (46°48'48"N;60°44'10"W) in bottom right. Topographic maps courtesy of Natural

Resources Canada.

2008 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 627

21 (see Shafer and Stewart [2006] for complete list). The high trap success rate (0.25

captures per 100 trap nights; Table 1) at MacDonald Pond for the Long-tailed Shrew

relative to other trapping expeditions in Nova Scotia (e.g., Shafer and Stewart 2006,

Woolaver et al. 1998) is worth discussing. Talus slopes are the preferred habitat of the

Long-tailed Shrew; however, they are often overlooked in small-mammal surveys.

One reason for this is that pitfall traps are difficult to place in the rocky substrate,

requiring a concerted trapping effort. Given our trapping success, we feel that the

Long-tailed Shrew is likely more widespread throughout Nova Scotia and Atlantic

Canada, although probably at low densities.

Through a total of 798 trap-nights (416 Victor snap trap, 382 pitfall) at MacDonald

Pond and 1766 trap-nights (740 Victor snap trap, 1026 pitfall) in the Grand Anse

Valley, two and one specimen(s) of Myodes (= Clethrionomys; Carleton et al. 2003)

gapperi Pallas (Southern Red-backed Vole) were collected as bycatch, respectively.

In the absence of a controlled population-density study, trap-night success can be

used as an index of abundance (Herman and Scott 1984). Comparing our Red-backed

Vole snap-trap bycatch to similar trapping efforts targeting Long-tailed Shrews in

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (Table 2), it is evident our success per 100 trapnights

is markedly lower (G-test of independence, G = 29.9, P < 0.001). Variation in

Table 1. Small-mammal captures from August 2006 on MacDonald Pond and Grand Anse Valley,

Nova Scotia. PF = pitfall trap, ST = snap trap, and TN = trap night.

Captures on Captures on the

Macdonald Pond Grand Anse Valley

Species Common name (416 PF, 382 ST) (1026 PF, 740 ST)

Blarina brevicauda Short-tailed Shrew 2 (0.25/100 TN) 22 (1.3/100 TN)

Sorex cinereus Masked Shrew 7 (0.88/100 TN) 43 (2.4/100 TN)

Sorex dispar/gaspensis Long-tailed Shrew complex 2 (0.25/100 TN) 2 (0.11/100 TN)

Sorex fumeus Smokey Shrew 45 (5.6/100 TN) 0 (0/100 TN)*

Sorex hoyi Pygmy Shrew 0 (0/100 TN) 3 (0.17/100 TN)

Microtus chrotorrhinus Rock Vole 0 (0/100 TN) 1 (0.06/100 TN)

Myodes gapperi Red-backed Vole 2 (0.25/100 TN) 1 (0.06/100 TN)

Napaeozapus insignis Woodland jumping Mouse 2 (0.25/100 TN) 7 (0.40/100 TN)

Peromyscus maniculatus Deer Mouse 0 (0/100 TN) 8 (0.45/100 TN)

*No species records on Cape Breton Island, NS, Canada.

Table 2. Myodes gapperi (Red-backed Vole) snap trap captures on rocky deciduous coniferous

forests in Nova Scotia (NS) and New Brunswick (NB), Canada. TN = trap-night.

No. of voles /

snap TNs Year

(per 100 TN ) Locality of study Reference

1 / 740 (0.14) Grand Anse Valley, NS 2006 This study

2 / 416 (0.48) Macdonald Pond, NS 2006 This study

14 / 900 (1.6) Stewart Mtn., NS 2005 Shafer and Stewart 2006

5 / 100 (5) Nerepis Hills, NB 2002 McAlpine et al. 2004

21 / 1799 (1.2) Smith Brook, NS 1986 Scott and Van Zyll de Jong 1989

21 / 1478 (1.4) Folly Mtn, NS 1984 Scott 1987

92 / 5699 (1.6) NS and NB (10 localities) 1978/1979 Kirkland and Schmidt 1982

8 / 306 (2.6) Albert County, NB 1978 Kirkland et al. 1979

73 / 500 (14.6) Grand Anse Valley, NS 1974 Roscoe and Majka 1976

628 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 15, No. 4

trapping success can be attributed to loss of bait; however, this was not likely a factor

because our traps were checked twice daily and bait reapplied as necessary.

The Grand Anse Valley site is the same location that was previously trapped by

Roscoe and Majka (1976) in August of 1974 (see Prescott et al. 1979; C. Majka, Nova

Scotia Museum of Natural History, Halifax, NS, Canada, pers. comm.). The survey

conducted by Roscoe and Majka (1976) yielded 73 Red-backed Voles in a total of

500 snap trap-nights. Our collection rate of a single Red-backed Vole in 740 snap

trap-nights is nearly 100 times lower than Roscoe and Majka (1976), and suggests a

population crash (G = 129.8, P < 0.001). Such a low number of captures is surprising

as peaks in population density typically take place during late summer (Merritt 1981)

when trapping occurred. Furthermore, Herman and Scott (1984) trapped throughout

Cape Breton Island and mainland Nova Scotia and found Red-backed Voles to be the

most abundant bycatch species (8.58 and 2.95 captures per 100 trap-nights).

Small-mammal bycatch data can be a useful measure of the local community

composition. Red-backed Voles of the genus Myodes are among the most common

small mammals throughout the Holarctic region. The Southern Red-backed Vole has

a Nearctic, primarily Canadian, distribution. In Nova Scotia, Red-backed Voles may

be the most abundant forest rodent (Scott and Hebda 2004), occurring in deciduous,

coniferous, and mixed forests (Merritt 1981). The Red-backed Vole is an opportunistic,

omnivorous feeder that often relies on seeds as a food source in the winter

(Merritt and Merritt 1978, Merritt 1981). Accordingly, the Red-backed Vole in Maine

has demonstrated cyclic population dynamics that correspond to Pinus strobus L.

(Eastern White Pine) seed fall (Elias et al. 2006).

Mid-winter conditions are critical to the reproductive success and survival of the

Red-backed Vole (Fuller et al. 1969). In particular, because Red-backed Voles do not

enter torpor, it often relies on low-quality food during the winter (Fuller et al. 1969).

The forest at the Grand Anse Valley site consists mainly of Betula alleghaniensis

Britt (Yellow Birch), which is not a mast-seed producer. It is therefore unlikely that

seeds make up a large portion of the Grand Anse Valley’s Red-backed Vole winter

diet. More likely, the opportunistic feeding of Red-backed Voles suggests a climatic

or epizootic explanation for the crash. Because bycatch numbers of other species are

relatively consistent with the data from Roscoe and Majka (1976), a species-specific

disease may be the cause. For example, the bycatch number of Napaeozapus insignus

Miller (Woodland Jumping Mouse) in our study did not significantly differ from

that reported by Roscoe and Majka (1976) (G = 1.04, P = 0.31). Herman and Scott

(1984) observed a similar trend in Nova Scotia when studying Peromyscus maniculatus

Wagner (Deer Mouse). In that study, Deer Mice numbers throughout mainland

Nova Scotia crashed while an insular island population remained constant, suggesting

an epizootic outbreak (Herman and Scott 1984). Concerted annual trapping in a

variety of habitats may be required to more precisely track the incidence of disease,

abundance, and distribution of these vole populations. Additional trapping studies

combined with necropsies are required to elucidate the cause(s) of the apparent crash

of Nova Scotia’s Red-backed Vole populations.

Acknowledgments. Trapping efforts were funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering

Research Council of Canada (grant 217175 to D.T. Stewart), New Brunswick

Wildlife Trust Fund, and the Atlantic Centre for Global Change and Ecosystem Research

at Acadia University. The Cape Breton Highlands National Park provided in-kind

support. Special thanks to John Gilhen, Andrew Hebda, Fred Scott, Lily Stanton, David

Stanton, Nathan Stewart, and Lauren McCarville for their help trapping. Thanks to Michael

Peckford and the two anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

2008 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 629

Literature Cited

Carleton, M.D., G.G. Musser, and L. Pavlinov. 2003. Myodes palla, 1811, is the valid name

for the genus of Red-backed Voles. In A. Averianov and N. Abramson (Eds.). International

Conference, Devoted to the 90th Anniversary of Professor I.M. Gromov, Saint

Petersburg. Russia.

Elias, S.P., J.W. Witham, and M.L. Hunter. 2006. A cyclic Red-backed Vole (Clethrionomys

gapperi) population and seedfall over 22 years in Maine. Journal of Mammalogy

87:440–445.

Fuller, W.A., L.L. Stebbins, and G.R. Dyke. 1969. Overwintering of small mammals near Great

Slave Lake, northern Canada. Arctic 22:34–55.

Herman, T.B., and F.W. Scott. 1984. An unusual decline in abundance of Peromyscus maniculatus

in Nova Scotia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 62:175–178.

Kirkland, Jr., G. 1981. Sorex dispar and Sorex gaspensis. Mammalian Species 155:1–4.

Kirkland, Jr., G., and D.F. Schmidt. 1982. Abundance, habitat, reproduction, and morphology

of forest-dwelling small mammals of Nova Scotia and Southeastern New Brunswick. The

Canadian Field-Naturalist 96:156–162.

Kirkland, Jr., G., and H.M. Van Deusen. 1979. The shrews of the Sorex dispar group: Sorex

dispar Batchelder and Sorex gaspensis Anthony and Goodwin. American Museum Novitates

2675:1–21.

Kirkland, Jr., G., D.F. Schmidt, and C.J. Kirkland. 1979. First record of the Long-tailed Shrew

(Sorex dispar) in New Brunswick. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 93:195–198.

McAlpine, D.F., S.L. Cox, D.A. McCabe, and J.-L. Schnare. 2004. Occurrence of the Longtailed

Shrew (Sorex dispar) in Nerepis Hills, New Brunswick. Northeastern Naturalist

11:383–386.

Merritt, J.F. 1981. Clethrionomys gapperi. Mammalian Species 146:1–9.

Merritt, J.F., and J.M. Merritt. 1978. Population ecology and energy relationships of Clethrionomys

gapperi in a Colorado subalpine forest. Journal of Mammalogy 59:576–598.

Prescott, W.H., B. Roscoe, and Majka, C. 1979. Small-mammal trapping program, 1974 and

1975 in Cape Breton Highlands National Park. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa, ON,

Canada. Mammal Section, Manuscript Reports. 237 pp.

Rhymer, J.M., J.M. Barbay, and H.L. Givens. 2004. Taxonomic relationship between Sorex

dispar and S. gaspensis: Inferences from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Journal of Mammalogy

85:331–337.

Roscoe, B., and C. Majka. 1976. First record of the rock vole (Microtus chrotorrhinus) and

the Gaspé shrew (Sorex gaspensis) from Nova Scotia and a second record of Thompson’s

pygmy shrew (Microsorex thompsoni) form Cape Breton Island. The Canadian Field-

Naturalist 90:497–498.

Scott, F.W. 1987. First record of the Long-tailed Shrew, Sorex dispar, from Nova Scotia. The

Canadian Field-Naturalist 101:404–407.

Scott, F.W., and A.J. Hebda. 2004. Annotated list of the mammals of Nova Scotia. Proceedings

of the Nova Scotia Institute of Science 42:189–208.

Scott, F.W., and C.G. Van Zyll De Jong. 1989. New Nova Scotia records of the long-tailed

Shrew, Sorex dispar, with comments on the taxonomic status of Sorex dispar and Sorex

gaspensis. Naturaliste Canadien 116:145–154.

Shafer, A.B.A., and D.T. Stewart. 2006. A disjunct population of Sorex dispar (Long-tailed

Shrew) in Nova Scotia. Northeastern Naturalist 13:603–608.

Woolaver, L.G., M.F. Elderkin, and F.W. Scott. 1998. Sorex dispar in Nova Scotia. Northeastern

Naturalist 5:323–330.

1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E9, Canada.

2Department of Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, B4P 2R6, Canada. *Corresponding

author - shafer@ualberta.ca.