Coral Lichen (Sphaerophorus globosus (Huds.) Vain) as an

Indicator of Coniferous Old-Growth Forest in Nova Scotia

Robert P. Cameron and Soren Bondrup-Nielsen

Northeastern Naturalist, Volume 19, Issue 4 (2012): 535–540

Full-text pdf (Accessible only to subscribers.To subscribe click here.)

Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Current Issue: Vol. 30 (3)

Check out NENA's latest Monograph:

Monograph 22

2012 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 19(4):535–540

Coral Lichen (Sphaerophorus globosus (Huds.) Vain) as an

Indicator of Coniferous Old-Growth Forest in Nova Scotia

Robert P. Cameron1,* and Soren Bondrup-Nielsen2

Abstract – Old-growth forests are rare and of conservation concern in Maritime Canada.

A variety of methods have been proposed to identify old-growth forests including structural

measurements and lichen surveys. Frequency and abundance of Sphaerophorus

globosus (Coral Lichen), was measured in 6 old-growth and 6 mature second-growth

coniferous forests in Nova Scotia. Total abundance (P = 0.013) and the tree frequency

occurrence (P = 0.005) were significantly greater in old-growth forests compared with

mature second growth in paired t-tests. We propose the abundance and frequency of

occurrence of the easily identifiable lichen Sphaerophorus globosus as an indicator of

old-growth forests. Forests with at least 25% of trees having Sphaerophorus globosus

growing on them, or meeting the criteria of at least 50 trees/ha with dbh >40 cm and more

than 25% of trees with Sphaerophorus globosus, should be studied further as potential

candidates for being assigned old-growth forest status.

Introduction

Old-growth forests in Maritime Canada comprise less than 1% of the total

forest (Mosseler et al. 2003). Because of this rarity and the unique assemblage

of species often found there, Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources has

a policy of maintaining at least 8% of a forest management area in old growth

(Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources 2007). The forest industry has

also recognized the importance of maintaining old growth and several large companies

in Nova Scotia have established old-growth reserve policies (Bax 2010,

Doucette and Miller 2009).

Recognizing true old growth has become a management concern. Assessment

methods and indicators have been developed in eastern North America to address

this concern. For example, Stewart et al. (2003) developed a method for determining

old growth in Nova Scotia which requires extensive field work involving

multiple measurements including time-consuming increment coring of trees.

Lichens were first proposed as indicators of ancient forests in Britain by Rose

(1976), and later Selva (1994) proposed a suite of lichens that could be used to

determine the continuity of forests in northeastern North America. Selva (2003)

also proposed that stubble lichens could be indicators of old growth. Recently,

McMullin et al. (2008) proposed another suite of lichen indicators for western

Nova Scotia. The greatest difficulty in the use of indicator suites of lichens is

that lichen experts are required to complete the assessment. Identification can be

time-consuming, involving collection and later identification with microscopes

and chemical tests.

1Nova Scotia Environment, PO Box 442, Halifax, NS, B3J 2P8, Canada. 2Department of

Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, B4P 2R6, Canada. *Corresponding author -

camerorp@gov.ns.ca.

536 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 19, No. 4

Those old-growth lichen indicator suites use presence as an indicator of old

growth but do not involve estimates of abundance or frequency. However, Whitman

and Hagan (2004) use the frequency of Usnea thalli >15 cm long as part of

an assessment of late successional coniferous forest in northern New England.

The use of Usnea species appears not to be appropriate in Nova Scotia because

the maritime influence results in Usnea species being ubiquitous and abundant.

There are more than 20 Usnea species occurring in the province, and some are

not exclusive to old forest (Cameron 2002, McMullin et al. 2008).

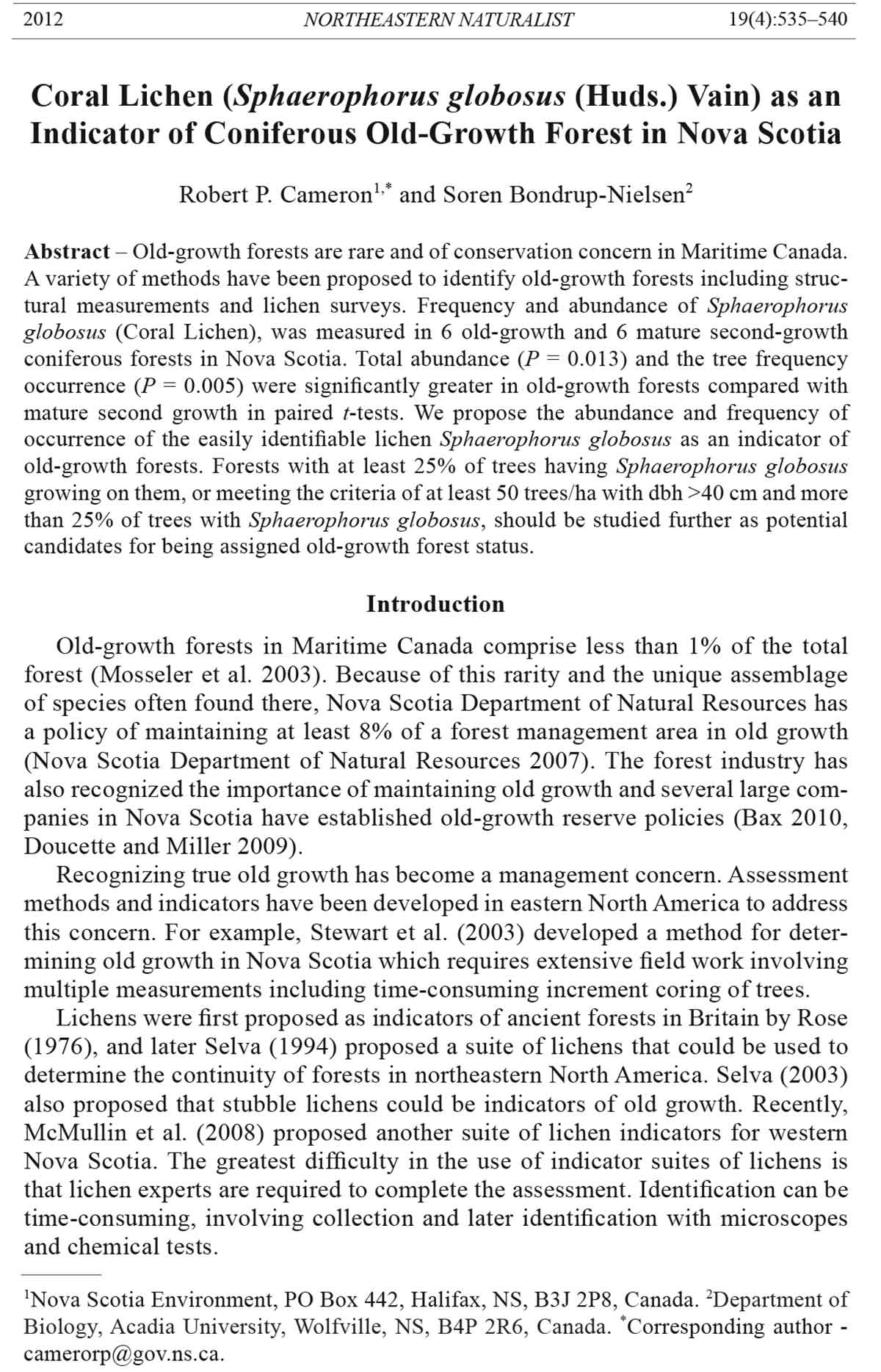

Sphaerophorus globosus (Huds.) Vain. (Coral Lichen) is one of the larger

fruticose lichens that is easily identified by amateurs (Fig. 1). The object of the

present study was to measure the abundance and frequency of Sphaerophorus

globosus on trees in old-growth forests and compare the data with studies in adjacent

mature second-growth forests to establish if this species could be used as

an old-growth coniferous forest indicator in Nova Scotia.

Methods

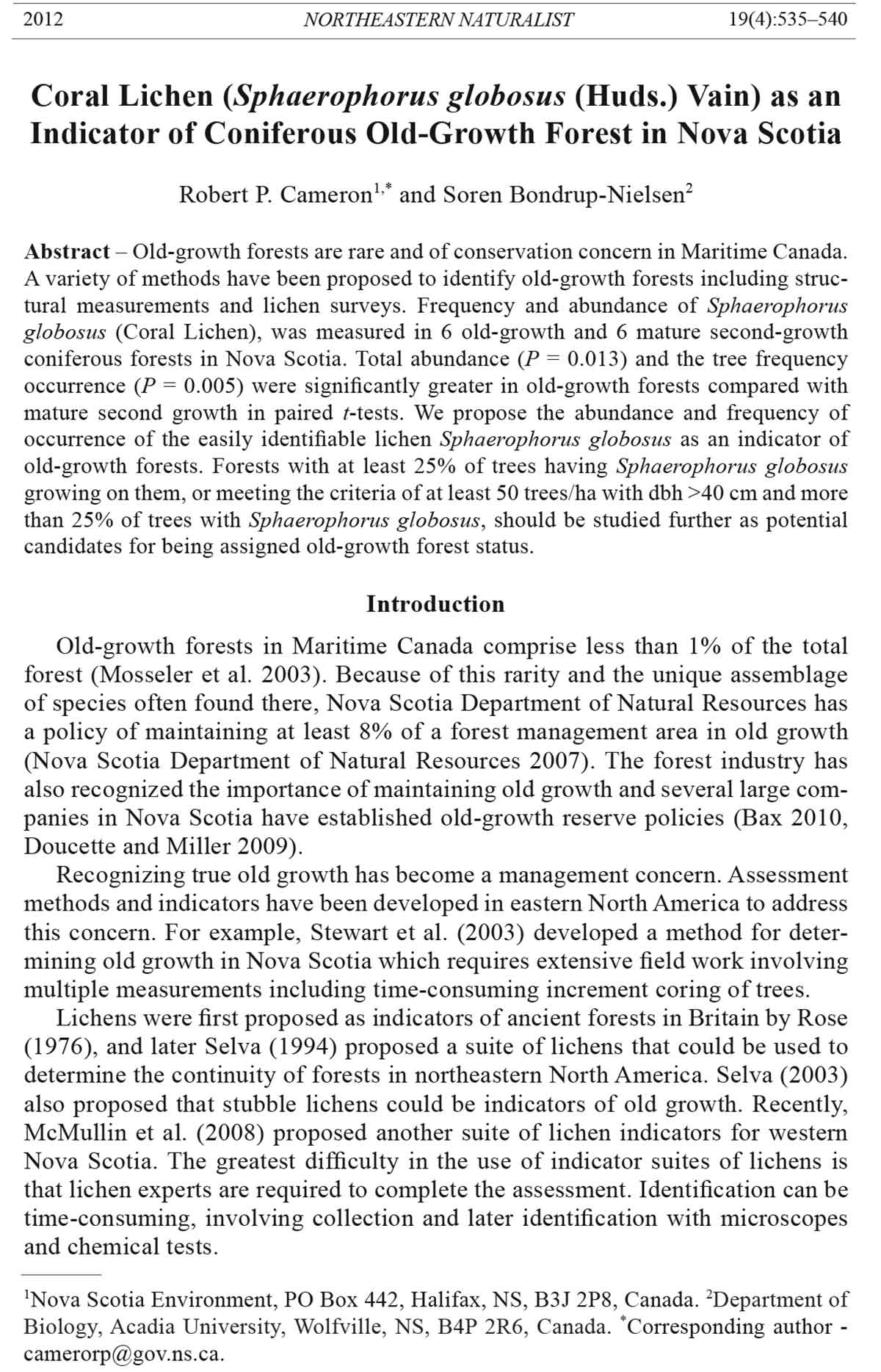

Six coniferous forests that were documented as being old growth (Cameron

2004) or met the criteria of Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources

(Stewart et al. 2003) were selected for study in Nova Scotia. As a comparison,

6 second-growth mature coniferous forests, within 5 km of each old-growth

forest, were also selected using Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources

forest inventory database (Table 1, Fig. 2). Mature forest, as defined in the forest

Figure 1. Sphaerophorus globosus (Coral Lichen) on Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrière

(Eastern Hemlock) in old-growth forest in central Nova Scotia.

2012 R.P. Cameron and S. Bondrup-Nielsen 537

inventory database, are stands ranging in age from 80 to 150 years as estimated

from remote data.

Transect lines were established that bisected each stand, and 6 points were

located at 35-m intervals along these transect lines and at least 50 m from the

edge of the stand. Each point became the center of a plot where a glass wedge

prism, with a basal area factor of 2 m2/ha, was used to identify trees to be sampled.

Of the trees identified from the prism sweep, 24 were selected such that

4 were picked from each of the 6 plots per stand. The first tree from each plot

Table 1. Coordinates of study sites in Nova Scotia, Canada where abundance and tree frequency of

Sphaerophorus globosus were measured.

Site name Stand maturity Longitude Latitude

S-Road Mature -64.1100 44.7500

Dayspring Mature -62.5830 45.2170

Governor Lake Mature -62.6700 45.1830

Armstrong Lake Mature -64.1830 44.8170

Panuke Lake Old growth -64.1100 44.7800

Abraham Lake Old growth -62.6300 45.1500

Card Lake Old growth -64.2600 44.7500

Rocky Lake Old growth -62.5500 45.2300

Calvary River Old growth -63.0393 45.4191

Browns Brook Mature -63.0411 45.4179

North River Old growth -60.6637 46.3184

MacDonald Brook Mature -60.6621 46.3185

Figure 2. Locations of Sphaerophorus globosus study sites in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Circles indicate locations of old-growth forest, and pluses indicate locations of mature

coniferous forest comparison sites.

538 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 19, No. 4

to be sampled for lichens was selected randomly, and the subsequent 3 trees

were selected sequentially and evenly from the trees identified from the prism

sweep. Since a prism sweep samples from a variable-sized plot, there was no

dependence in terms of the distance between sampled trees, which ensured that

the 24 trees sampled for lichens within a stand were independent. Both live

and dead trees were sampled.

The occurrence of Sphaerophorus globosus up to 2 m from the ground on tree

trunks was recorded for each tree, and its abundance was measured as percent

cover of the tree surface. Percent cover was estimated from ground level to 2 m

up the bole of each tree on all sides of the tree and scored according to the following

scale: 1 = rare (<1% cover); 2 = occasional (1 to 2% cover); 3 = common

(2 to 10% cover); and 4 = abundant (>10% cover). Cumulative abundances and

tree frequency occurrence was calculated for each stand for use in comparative

analyses. Presence of fruiting bodies on thalli was not recorded.

Paired t-test was used to compare differences between cumulative abundance

and tree frequency occurrence of Sphaerophorus globosus for each site between

old growth and second growth.

Results and Discussion

Sphaerophorus globosus is a lichen that in Nova Scotia occurs in greatest

abundance in old-growth forests (Cameron 2002). It was included by McMullin

et al. (2008) and Selva (1996) in their old-growth forest indicator suites. In the

present study, the total abundance (P = 0.013) and tree frequency occurrence (P =

0.005) were significantly greater in old-growth forest compared to second growth

with paired t-tests (Table 2). Only 1 old-growth stand had fewer than 10 trees per

24 with Sphaerophorus globosus. The presence of Sphaerophorus globosus alone

appears not be a useful predictor of old-growth coniferous forest in Nova Scotia

since it can also be found in second-growth forest. However, as stated above, its

abundance and frequency on trees may enable it to be a rapid and easily assessed

identifier of old-growth forests.

Sphaerophorus globosus is well-known to be common in old-growth forests

(Cameron 2002, McMullin et al. 2008, Selva 1994, Sillet and Goslin 1999). Of

51 forest stands studied by McMullin et al. (2008) in southwest Nova Scotia,

Sphaerophorus globosus was found only in stands greater than 211 years old.

When Sphaerophorus globosus was found in second-growth forest in Nova

Table 2. Sphaerophorus globosus total abundance and frequency of occurrence on trees in old

-growth and second-growth coniferous forest in Nova Scotia.

Total abundance Frequency

Forest pair Old growth Second growth Old growth Second growth

1 34 0 16 0

2 43 2 14 2

3 20 1 10 1

4 69 1 23 1

5 5 0 3 0

6 29 0 19 0

2012 R.P. Cameron and S. Bondrup-Nielsen 539

Scotia, it was associated with legacy trees (Cameron 2002). Sillet and Goslin

(1999) found a similar trend with second growth in British Columbia, Canada.

In old-growth forests, it is found on the trunks of hemlock, pine (Pinus spp.),

and spruce (Picea spp.) but it can also be found on soil or rock (Hinds and

Hinds 2007).

Sphaerophorus globosus is easily identified in the field. It usually consists of

several main branches ascending from a central larger main stem (Fig. 1). The

sides and tips of main branches have tufts of fine branches, giving the lichen a

delicate appearance. The color varies from green to greenish gray to brown, often

with an orange tinge. Reproductive structures that consist of round apothecia may

occur at the ends of branches.

Some caution may be required when using Sphaerophorus globosus as an oldgrowth

forest indicator in coastal forests. A greater level of moisture, as a result

of frequent fog and high rainfall, may result in a high abundance of Sphaerophorus

globosus in forests that are not true old growth.

The number of old-growth forests sampled in this study was necessarily low

because there are so few old-growth forest stands left in Nova Scotia. Further

studies in adjacent provinces, such as Newfoundland and Labrador, could increase

sample size and help determine if this species is a reliable old-growth

indicator for a wider geographic region. Interestingly, Sphaerophorus globosus

is only found on trees at one site in Maine, USA—Roque Island—which is one

of the few remaining old-growth forest stands in the state (D. Richardson, Saint

Mary’s University, Halifax, NS, Canada and M. Seaward, Bradford University,

Bradford, UK, unpubl. data).

Sphaerophorus globosus could be used as an indicator in two ways. Firstly,

it can be used as an initial rapid assessment for potential old-growth forests.

Surveyers can first assess the abundance of Sphaerophorus globosus and if old

growth is indicated, they can follow up with more detailed protocols as outlined

by Selva (1994), Stewart et al. (2003) or McMullin et al. (2008). Based on the

results of the present study, indication of old growth is when at least 25% of trees

have Sphaerophorus globosus. At least 20 trees should be examined from ground

level to 2 m above ground on the bole. Surveyors should look for well-developed,

mature, easily identifiable lichens. If 5 or more trees per 20 have Sphaerophorus

globosus, then the stand has a high likelihood of being old growth and further

assessment should be done.

The second approach is to use Sphaerophorus globosus in concert with other

indicators, as suggested by Whitman and Hagan (2004). These researchers used

lichen density and large-diameter tree density to assess late successional forest.

They found tree diameter to be the single best indicator of late successional forest

in northeastern US. This method could be adapted to Nova Scotia by using

both Sphaerophorus globosus frequency and tree-diameter criteria suggested by

Stewart et al. (2003) for Nova Scotia. To qualify as old growth, a forest would

need to meet the criteria of at least 50 trees/ha with a diameter at breast height

greater than or equal to 40 cm. In addition, greater than or equal to 25% of the

trees in the stand would have to have Sphaerophorus globosus.

540 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 19, No. 4

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank field assistants Jan McPhee and Glenn Davis. Special thanks

to Julie Towers for review of an early draft and assistance in the field. We also thank

David Richardson, Jim Hinds, and Scott LaGreca for helpful comments on the submitted

manuscript. Financial support was provided by Bowater Mersey Paper Company Ltd.,

Kimberly-Clark Ltd., Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources-Wildlife Division,

and StoraEnso Port Hawkesbury Ltd. Financial and technical support was made possible

by the following people of these organizations: Tony Duke, Peter Jones, Bevan Lock,

Gerald Peters, John Porter, Steve Rutledge, and Russ Waycott. Karen Casselman and

David Richardson provided assistance on lichen identification.

Literature Cited

Bax, H. 2010. Forest certification report. QMI-SAI Global. Available online http://www.

qmi.com/registration/forestry/fsc/BowaterMerseyFSC2009PublicReport.pdf. Accessed

16 January 2012.

Cameron, R.P. 2002. Habitat features associated with epiphytic lichens in managed and

unmanaged forests in Nova Scotia. Northeastern Naturalist 9:27–46.

Cameron, R.P. 2004. Resource guide and ecological atlas: For conducting research in

Nova Scotia’s wilderness areas and nature reserves. Protected Areas Branch, Nova

Scotia Environment and Labour Technical Note 0401. Halifax, NS, Canada.

Doucette, A., and C. Miller. 2009. High Conservation value forest assessment New Page

Port Hawkesbury Forest Management Area, New Page Port Hawkesbury. 131 pp.

NewPage, Port Hawkesbury, NS, Canada.

Hinds, J.W., and P.L. Hinds. 2007. The Macrolichens of New England. The New York

Botanical Garden Press, New York, NY. 584 pp.

McMullin, R.T., P.N. Duinker, R.P. Cameron, D.H.S. Richardson, and I.M. Brodo. 2008.

Lichens of coniferous old-growth forests of southwestern Nova Scotia, Canada: Diversity

and present status. The Bryologist 111:620–637.

Mosseler, A., J.A. Lynds, and J.E. Major. 2003. Old-growth forests of the Acadian Forest

Region. Environmental Reviews 11:S47–S77.

Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources. 2007. Interim old-forest policy. Available

online at http://www.gov.ns.ca/natr/forestry/planresch/oldgrowth/policy.htm.

Accessed 15 January 2012.

Rose, F. 1976. Lichenological indicators of age and environmental continuity in woodlands.

Pp. 279–307, In D.H. Brown, D.L. Hawksworth, and R.H. Bailey (Eds.). Systematics

Association Special Volume No. 8, Lichenology: Progress and Problems.

Selva, S.B. 1994. Lichen diversity and stand continuity in the northern hardwoods and

spruce-fir forests of northern New England and western New Brunswick. The Bryologist

93:380–381.

Selva, S.B. 2003. Using calicioid lichens and fungi to assess ecological continuity in the

Acadian Forest Ecoregion of the Canadian Maritimes. Forestry Chronicle 79:550–558.

Sillett, S.C., and M.N. Goslin. 1999. Distribution of epiphytic macrolichens in relation

to remnant trees in a multiple-age Douglas-fir forest. Canadian Journal of Forest Research

29:1204–1215.

Stewart, B.J., P.D. Neily, E.J. Quigley, A.P. Duke, and L.K. Benjamin. 2003. Selected

Nova Scotia old-growth forests: Age, ecology, structure, scoring. Forestry Chronicle

79:632–644.

Whitman, A.A., and J.M. Hagan. 2004. A rapid assessment late-successional index for

northern hardwoods and spruce fir forests. Forest Mosic Science Notes. Manoment

Centre for Conservation Science, Brunswick, ME. FMSN-2004-3. 4 pp.