2013 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 20(3):493–497

Effects of Prescribed Fire on the Eastern Box Turtle

(Terrapene carolina carolina)

Christopher A.F. Howey1,* and Willem M. Roosenburg1

Abstract - While conducting an on-going project investigating the effects of prescribed

fire on reptile communities, 31 Terrapene carolina carolina (Eastern Box Turtle) were

captured in burned and unburned study sites; some with extensive injuries that were

likely caused by a recent prescribed burn. In order to determine if the disturbance had

any negative effects on the turtles, we recorded morphometrics, mass, sex, and injuries

for each one captured. Twenty percent of box turtles in the burned area exhibited injuries

caused by the fire. Turtles in burned sites were similar in length but weighed significantly

less (df = 1, F = 5.255, P = 0.0329) and had a poorer body-condition index than turtles in

unburned sites. Additionally, one injured box turtle was encountered 32 times in a burned

site. On average, this individual moved 22.5 m/day within a 3.77 ha home range. Over

the course of 1 year, the turtle grew 1.3 mm and gained 27 g. The injuries to the carapace

of this individual never fully healed during that year, and the scutes did not grow back;

however, regeneration of the carapace may require a longer period of time. These scant

data suggest that Eastern Box Turtles may not respond favorably to prescribed fire, and

indicate that additional studies are needed to increase knowledge of the effects of prescribed

fire on this species.

Introduction

Prescribed burning has become a popular tool in forestry management used to

create a more open, early successional habitat; however, it is unclear how most

reptiles respond to this landscape disturbance. Terrapene spp. (box turtles) reportedly

suffer high rates of mortality and/or extensive injuries as a result of the

direct effects of fire (Allard 1949, Babbitt and Babbitt 1951, Bigham et al. 1964,

Dolbeer 1969). Due to the slow movements of box turtles and their tendency to

take shelter in leaf litter, box turtles may not be able to avoid a fire as it passes

through the landscape. If box turtles survive the fire, they are sometimes left with

extensive injuries that may lead to the partial or complete loss of the epidermal

layer (scutes) of the shell (Babbitt and Babbitt 1951, Rose 1986). Regeneration of

the scutes has been documented in a few instances (Rose 1986), but it is unclear

if this phenomenon is common, how these animals will cope with the changed

landscape, and if the health of the animal will improve or deteriorate in these

altered environments.

Methods

Terrapene carolina carolina L. (Eastern Box Turtle) were captured in burned

and unburned sites between 2010 and 2011 as part of a larger study. The burned

1Ohio Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Studies, Department of Biological Sciences,

Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701. *Corresponding author - chris.howey@gmail.com.

C.A.F. Howey

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 3

494

sites had been recently subjected to a prescribed fire (September 2010), and were

located in the Franklin Burn Unit at Land-Between-the-Lakes National Recreational

Area, KY. Morphometrics, mass, sex, and the presence of injuries were

recorded for each captured turtle. Additionally, each captured turtle was uniquely

marked (Cagle 1939) prior to its release.

One severely injured, adult male Eastern Box Turtle was recaptured multiple

times over the course of a year in a burn site (Fig. 1). Upon each encounter with

the turtle, GPS coordinates, morphometrics, mass, and condition of the injuries

to the carapace were recorded. These data were used to determine if there was a

change in morphometrics, mass, or condition of injuries over the course of the

year. GPS coordinates were analyzed with Home Range Tools 1.0 extension in

ArcGIS 9.3 (Rodgers et al. 2007) to determine movement rates and home-range

size based on a 95% Kernal estimate.

Results and Discussion

In total, 31 Eastern Box Turtles were captured in burned and unburned study

sites—20 turtles in burned sites and 11 in unburned sites. All turtles captured in

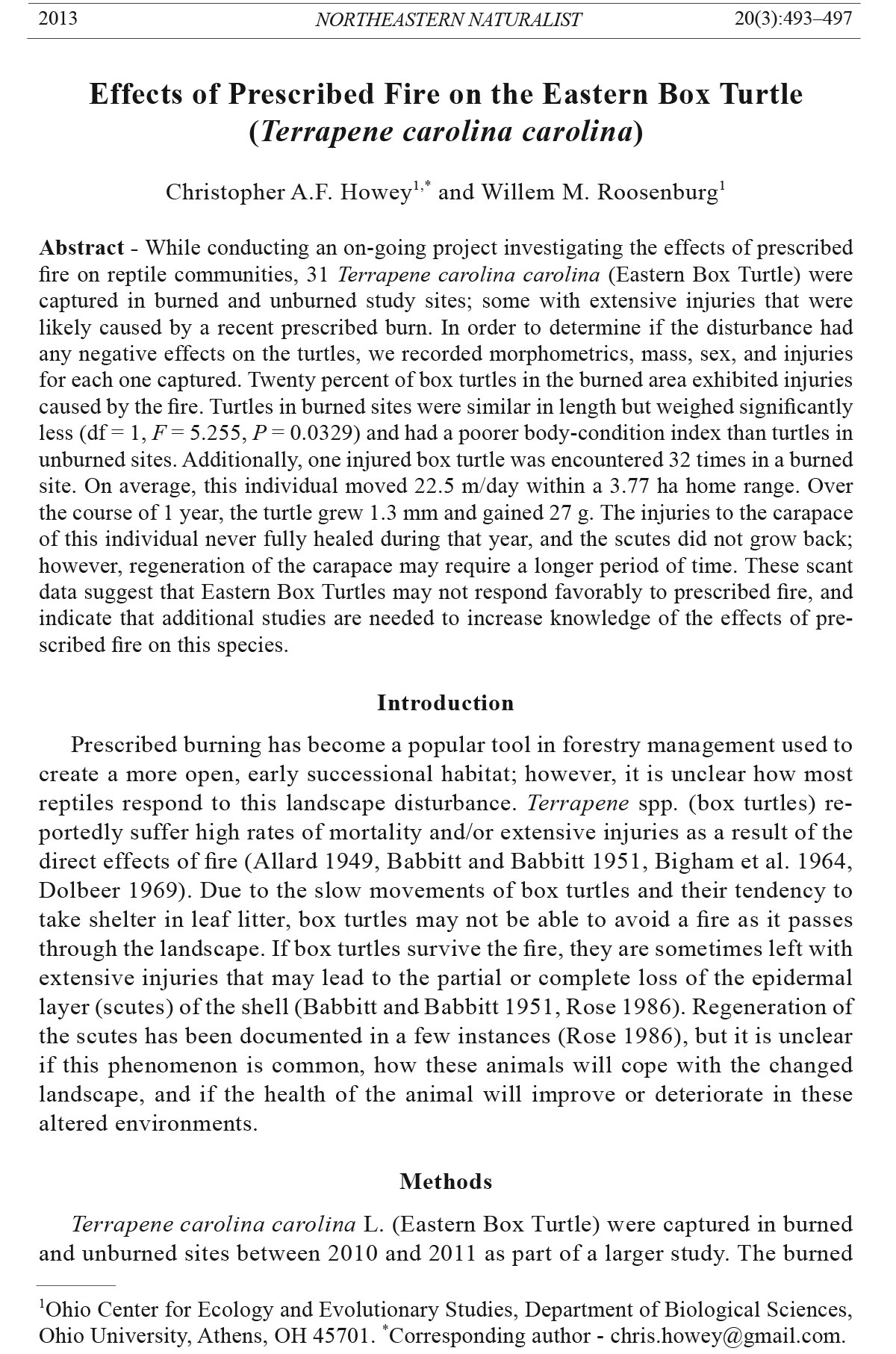

Figure 1. Eastern Box Turtle with injuries from a prescribed fire. The front vertebral

(denoted by “V” ) and right and left pleural scutes (denoted by “P”) are discolored and

weakly attached to the carapace. All other vertebral and pleural scutes have fallen off of

the carapace. Marginal scutes (surrounding the perimeter of the carapace) and plastron

appear to be unaffected.

495

C.A.F. Howey

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 3

unburned sites were uninjured; however, 20% of turtles captured in burned sites

exhibited injuries that were presumably caused by fire. Injuries mostly consisted

of damaged or missing pleural and vertebral scutes (Fig. 1); these scutes would

be the most vulnerable if the animal were buried in the leaf litter at the time of

the fire. Mean carapace length was 127.1 mm and 130.4 mm for uninjured and

injured turtles respectively; however, mean mass was greater for uninjured compared

to injured turtles (405.8 and 385.5 g, respectively). All turtles in burned

sites (injured and uninjured) had a significantly lower body mass (mean = 373.3

g) than those found in unburned areas (mean = 448.0 g) when carapace length

was used as a covariate (df = 1, F = 5.255, P = 0.0329). In addition to the lower

body mass, turtles that were found in burned sites also had a lower body condition

index (Fig. 2), which may suggest poorer health of these animals. It is

possible that the warmer ground temperatures and higher total radiation of the

burn sites (C.A.F. Howey, unpubl. data) led to greater body water loss; and thus,

lower body mass for turtles in burned areas. Additionally, the loss of the outer

dermal layer of the shell (i.e., scutes) may exaggerate this loss of body water and

lead to a lower mass and poorer body condition. Degraded habitat may also contribute

to a diminished body condition, but data on habitat use was not recorded

for box turtles during this project. We hope that the scant data presented here may

Figure 2. Body condition index of Eastern Box Turtles is determined by the residuals

from the mean (regression line). Black squares denote turtles from burn sites. Gray circles

denote turtles from unburned sites.

C.A.F. Howey

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 3

496

spur future work examining the effect of such injuries and the effect of a changed

landscape on the Eastern Box Turtle. It appears that surviving a prescribed burn

is only the first challenge for Eastern Box Turtles; maintaining a healthy body

condition may also be difficult in these disturbed landscapes.

One severely injured, adult male Eastern Box Turtle was encountered 32 times

between 30 May 2011 and 8 June 2012. Over the course of the year, the turtle

grew 1.3 mm and gained 27 g. The state of the injuries did not change over the

year; scutes that were missing did not grow back, and scutes that were severely

damaged still appeared damaged after one year (Fig. 1). Shell regeneration has

been reported for box turtles (Rose 1986); however, this phenomenon may require

more than one year. Over the course of the year, the turtle moved on average

22.5 m per day with a maximum movement of 60.8 m per day. The home range

for the turtle was 3.77 ha, and over the course of the year the turtle was never

found outside of a small valley. Although we did not record habitat characteristics

associated with the valley, greater amounts of canopy cover and understory

vegetation were observed in this area compared to surrounding habitat in the

burned landscape. In comparison to other Eastern Box Turtle studies, the home

range of this individual was equal to or smaller than previously reported home

ranges (Hester et al. 2008, Madden 1975, Wilson 2001), but movement rates were

less than the mean for turtles that occupy undisturbed, forested landscapes (40

m/day; Strang 1983). Interestingly, Iglay et al. (2007) found lower movement

rates for Eastern Box Turtles in habitat disturbed by fragmentation, which were

comparable to the movement rates for the individual in this study. It is possible

that the lower movement rate for the injured turtle is the result of reducedquality

habitat rather than the result of its injuries, but this is purely speculation.

Given these data, further work regarding the habitat use of Eastern Box Turtles

in burned and unburned landscapes is warranted. If box turtles can survive the

direct effects of prescribed fire, it is unclear if this altered landscape will provide

favorable habitat characteristics for the species, how habitat changes will affect

movement rates and home-range sizes, and ultimately energetic expenditures and

fitness of Eastern Box Turtles.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted in compliance with state (SC1211012) and federal

(LBL10165) permits. The research was supported by funding from the National Fire Plan

through the US Forest Service’s Northern Research Station (10-CR-11242302-056). All

interactions with animals were approved under the Ohio University IACUC L09-08. We

thank M. Dickinson for assistance with this project and with obtaining funding for this

project. I thank A. Schneider, E. Stulik, R. Everett, N. Becker, B. Johnson, and K. Heckler

for assistance with data collection.

Literature Cited

Allard, H.A. 1949. The Eastern Box Turtle and its behavior. Journal of the Tennessee

Academy of Science 24:146–152.

497

C.A.F. Howey

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 3

Babbitt, L.H., and C.H. Babbitt. 1951. A herpetological study of burned-over areas in

Dade County, Florida. Copeia 1951:79.

Bigham, S.R., J.L. Hepworth, and R.P. Martin. 1964. A casualty count of wildlife following

a fire. Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science 45:47–50.

Cagle, F.R. 1939. A system of marking turtles for future identification. Copeia

1939:170–173.

Dolbeer, R.A. 1969. Population density and home-range size of the Eastern Box Turtle

(Terrapene c. carolina) in eastern Tennessee ASB Bulletin. 16:49.

Hester, J.M., S.J. Price, and M.E. Dorcas. 2008. Effects of relocation on movements and

home ranges of Eastern Box Turtles. Journal of Wildlife Management 72:772–777.

Iglay, R. B., J.L. Bowman, and N.H. Nazdrowicz. 2007. Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene

carolina carolina) movements in fragmented landscape. Journal of Herpetology

41:102–106.

Madden, R.C. 1975. Home range, movements, and orientation in the Eastern Box Turtle,

Terrapene carolina carolina. Ph.D. Dissertation. The City University of New York.

New York, NY.

Rodgers, A.R., A.P. Carr, H.L. Beyer, L. Smith, and J.G. Kie. 2007. HRT: Home Range

Tools for ArcGIS. Version 1.1. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Centre for

Northern Forest Ecosystem Research, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada

Rose, F.L. 1986. Carapace regeneration in Terrapene (Chelonia: Testudinidae). The

Southwestern Naturalist 31:131–134.

Strang, C.A. 1983. Spatial and temporal activity patterns in two terrestrial turtles. Journal

of Herpetology 17:43–47.

Wilson, G.L. 2001. Reproductive ecology of the Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina

carolina) in a mixed oak-pine woodland in the central Virginia Piedmont. Virginia

Journal of Science 52:86–87.