2013 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 20, No. 3

N8

C.D. Rockey, J.P. Stumpf, and A. Kurta

Additional Winter Recoveries of Indiana Bats (Myotis sodalis)

Banded during Summer in Michigan

Craig D. Rockey1, Joshua P. Stumpf1, and Allen Kurta1,*

Abstract - We report 4 new recoveries of the endangered Myotis sodalis (Indiana Bat) that were

banded in Michigan during summer and found hibernating in Ohio, Indiana, or Kentucky, 225–386

km from the initial banding site. A fifth individual apparently made the longest migration on record

for Indiana Bats (575 km) on multiple occasions. Since 1997, 15% of 71 Indiana Bats banded in

Michigan during summer have been recovered during winter.

Seasonal migration can be costly in terms of energy and time and often increases the

risk of certain types of mortality, such as predation or deaths due to cold or wet weather

(Fleming and Eby 2003). For temperate insectivorous bats, the stress of migration is

exacerbated because migration is often sex-biased, with adult females traveling farther

than most males (Cryan and Veilleux 2007, Kurta 2010). The females make their journey

in spring, while in the early stages of pregnancy, and in late summer, the migrating population

includes inexperienced young-of-the-year. Migration is particularly problematic

for endangered species because this behavior can intensify the risk of extinction (Cryan

2011, US Fish and Wildlife Service 2007). Therefore, any knowledge of migratory patterns

is potentially useful to wildlife managers.

Myotis sodalis Miller and Allen (Indiana Bat) is an endangered species that lives

in much of the eastern and midwestern United States (US Fish and Wildlife Service

2007). In summer, males are solitary, whereas females typically form maternity colonies

and roost behind the loose bark of dead trees, where they give birth and raise their

single young. Both sexes hibernate in caves or mines during winter. In the Midwest,

most Indiana Bats overwinter in southern Indiana, Kentucky, or Missouri, and they migrate

generally northward in spring, with females moving greater distances than males

(Gardner and Cook 2002, Whitaker and Brack 2002). For example, only 11% of adult

Indiana Bats captured in southern Lower Michigan are male (Kurta and Rice 2002). A

few Indiana Bats banded in Michigan previously have been discovered during hibernation

(Winhold and Kurta 2006), and in this paper, we describe 4 new recoveries, of

Indiana Bats that originally were banded during summer in Lenawee County, MI. In

addition, we report 2 new sightings of an individual that was banded initially during

summer in Jackson County, MI, and first found hibernating in Kentucky in 2005.

Between 1995 and 2007, biologists from Eastern Michigan University banded 51 Indiana

Bats during summer in southern Lower Michigan (e.g., Kurta et al. 2002, Winhold

2007). The bands were imprinted with a 4-digit number and the letters “EMU YPSI MI”,

which represented our university, city, and state, respectively. Range-wide, the size of

the population of Indiana Bats is determined every 2 years, in winter, when the bats are

concentrated in their hibernacula (US Fish and Wildlife Service 2007). All recaptures of

banded animals that we discuss occurred during these biennial counts.

The four newly recovered bats originally were banded within the home range of a

maternity colony of Indiana Bats, about 5 km south of Palmyra, Lenawee County, MI. A

male young-of-the-year, banded on 5 August 2004, was recaptured on 14 January 2007

1Department of Biology, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI 48197. *Corresponding author

- akurta@emich.edu.

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 20/3, 2013

Northeastern Naturalist Notes

N9

2013 Vol. 20, No. 3

C.D. Rockey, J.P. Stumpf, and A. Kurta

in Grotto Cave, Monroe County, IN. A female young-of-the-year, originally caught on 25

July 2006, was found hibernating on 29 January 2007 in Ray’s Cave, Greene County, IN.

The third bat was banded on 6 July 2007, when lactating, and recaptured on 22 November

2009 in Saltpeter Cave, Carter County, KY. The approximate distance between site of

banding and recovery for these bats was 376, 386, and 378 km, respectively (Fig. 1).

A fourth banded bat roosted high in the Lewisburg Limestone Mine, Preble County,

OH (Fig. 1), on 18 February 2012, and could not be reached by the surveyors; consequently,

a photograph was taken of the exposed part of the band. The letters “YPSI”

were visible in the photograph, but only 2 digits (“73”) could be seen. Nevertheless, the

numeral “3” was below the “I” of “YPSI”, indicating that the “3” was the last digit of our

4-digit number. Our records showed that only one Indiana Bat ever received a band with a

number ending in “73”—#6473, an adult female, banded on 14 May 2007, near Palmyra,

about 225 km from the Lewisburg Limestone Mine.

In addition to the previously unreported individuals from Palmyra, an adult female

was found hibernating in Colossal Cave, Edmonson County, KY, on the grounds of Mammoth

Cave National Park, on both 24 January 2007 and 8 February 2011. This individual

was 1 of 5 Indiana Bats mist-netted along a wooded fenceline, about 3 km southeast of

Norvell, Jackson County, MI, and banded on 27 May 2004 (Winhold et al. 2005). The bat

was first found hibernating in Colossal Cave on 3 February 2005, as reported by Winhold

and Kurta (2006). The distance between Norvell and Colossal Cave is about 575 kilometers,

which is the longest migratory distance on record for any Indiana Bat (Fig. 1;

Winhold and Kurta 2006, US Fish and Wildlife Service 2007). Although we cannot be

certain whether this individual summered in Michigan each year between 2005 and 2010,

Indiana Bats are philopatric, and many individuals have been recaptured, near their original

banding site, in summers following initial capture (e.g., Gardner et al. 1991, Gumbert

et al. 2002, Kurta and Murray 2002, Winhold et al., 2005). Therefore, it seems likely this

bat has made the 575-km journey between Norvell and Colossal Cave many times.

The animal found in the Lewisburg Limestone Mine was the first Indiana Bat from

Michigan known to hibernate in Ohio and the first banded in summer to be found overwintering

in a mine; all others had been discovered in caves (Winhold and Kurta 2006).

Distance traveled by this bat (225 km) was 151 km less than the shortest known migratory

distance for any other Indiana bat from Michigan (this study, Winhold and Kurta 2006).

The Lewisburg Mine has been available for use by bats only for the last 30 years (Brack

2007) and provides a manmade hibernaculum in an area without other suitable sites for

overwintering. Although maximum migratory distances of Indiana Bats from the Midwest

appear much greater than those of Indiana bats in the East (US Fish and Wildlife Service

2007), we suggest that this difference is only due to geology. In contrast to the East, all

of southern Michigan, northern Indiana, and northern Ohio is covered by many meters of

glacial till so that caves or mines are rare or nonexistent (e.g., Dorr and Eschman 1970,

Powell 1961), and Midwestern bats simply are forced to fly farther between suitable sites

for summer and winter than those in the East.

The 4 new returns corroborated the findings of Winhold and Kurta (2006), who reported

that members of the maternity colony of Indiana Bats near Norvell did not winter in

the same hibernaculum or even in the same general region of the Midwest (Fig. 1). These

4 recent recoveries represented banded bats from a different maternity colony (Palmyra),

located about 40 km southeast of Norvell, and these new individuals hibernated in 4

separate locations, up to 325 km apart (Fig. 1). Average distance between site of summer

banding and winter recovery for the 4 recent individuals was 341 ± 19 (SE) km. When we

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 20, No. 3

N10

C.D. Rockey, J.P. Stumpf, and A. Kurta

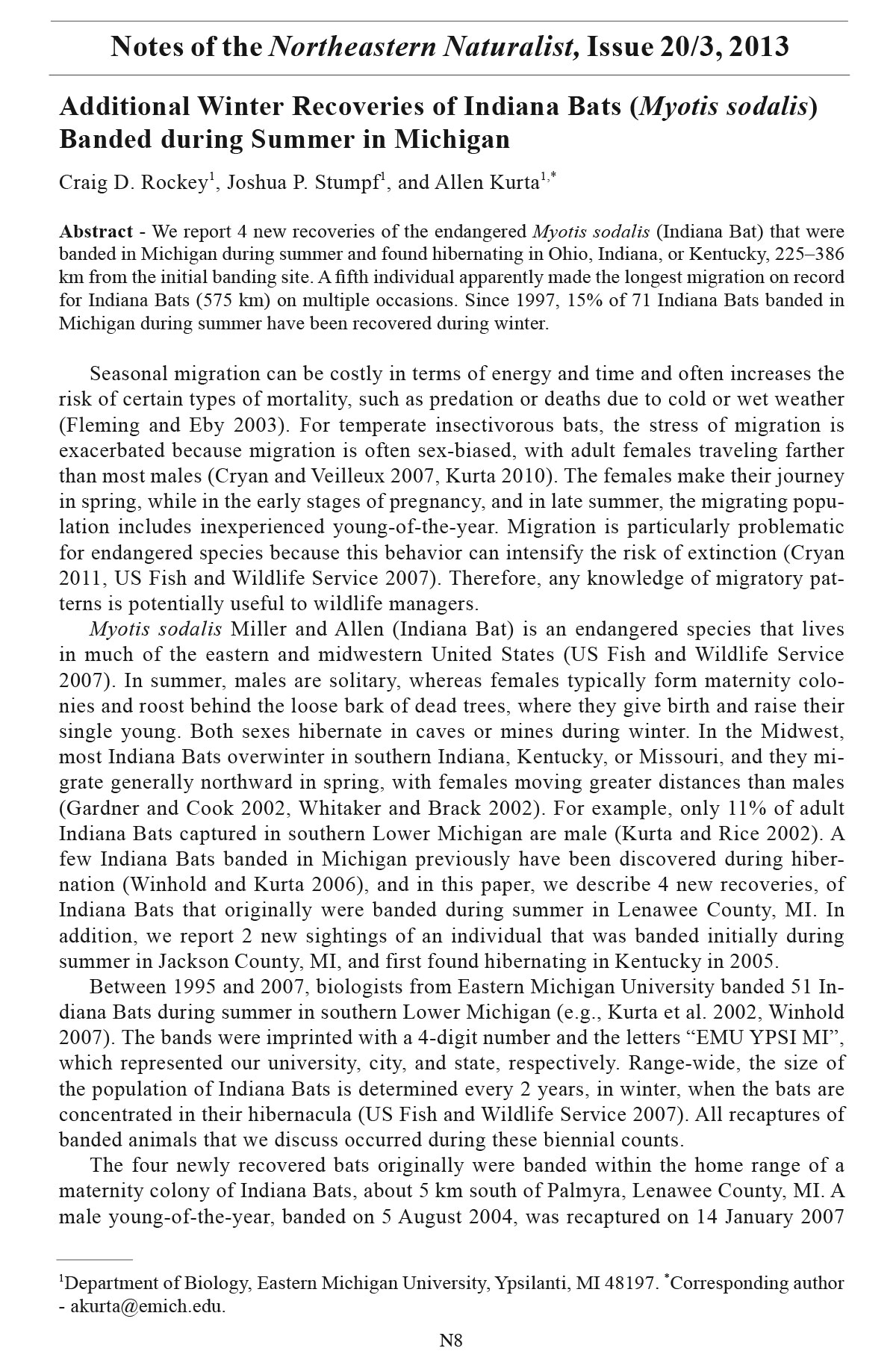

Figure 1. Map showing approximate location of hibernacula used by Indiana Bats that were banded

in Michigan during summer. Shaded symbols represent a maternity colony near Palmyra, MI, and

associated hibernacula. Open symbols denote a maternity colony near Norvell, MI, and associated

hibernacula, as reported by Winhold and Kurta (2006). Letters represent locations specifically mentioned

in the text: A = Palmyra, B = Norvell, C = Ray’s Cave, D = Grotto Cave, E = Colossal Cave,

F = Saltpeter Cave, and G = Lewisburg Limestone Mine. Ray’s Cave (C) was used for hibernation

by individuals from the maternity colonies at both Norvell and Palmyra.

Northeastern Naturalist Notes

N11

2013 Vol. 20, No. 3

C.D. Rockey, J.P. Stumpf, and A. Kurta

combine the new recoveries from the colony near Palmyra with 7 previously reported in

the literature from Norvell (Winhold and Kurta 2006), average migratory distance for all

11 bats is 429 ± 23 km. These 11 Indiana Bats from two maternity colonies in Michigan

were found in 10 different hibernacula; only Ray’s Cave was used by individuals from

both the summer colonies at Norvell and Palmyra.

Although the costs of migration often are viewed in terms of time, energy, and predation

(Fleming and Eby 2003), Indiana Bats migrating between Michigan and Indiana,

Ohio, or Kentucky are faced with new challenges. Wind-energy developments are becoming

common in the Midwest, and many species of bats, including Indiana Bats, have

been killed by wind turbines in these states, through collisions and/or barotrauma (Ellison

2012, US Fish and Wildlife Service 2012a). Band recoveries do not indicate specific

routes that bats actually take during migration, but they do identify the starting and ending

points of migration and suggest possible trajectories that should be considered by

developers of wind farms, as they attempt to prevent the deaths of these endangered bats.

In addition, migration likely plays a role in the spread of Geomyces destructans, a psychrophilic

fungus that has caused the death of more than 5 million hibernating bats since

2007 (Turner et al. 2011, US Fish and Wildlife Service 2012b). This disease (white-nose

syndrome) is still absent from the central and western basins of the Great Lakes. However,

at least 3 of the hibernacula used by Indiana Bats from Michigan are infected as of winter

2011–2012: Grotto Cave, Batwing Cave (L. Pruitt, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bloomington,

IN, pers. comm.) and the Lewisburg Mine (L.M. Walker, Environmental Solutions

and Innovations, Cincinnati, OH, pers. comm.). Spores of the fungus have been detected

at maternity roosts of other species (Dobony et al. 2011), suggesting that at least some

transmission may occur during summer. The fact that Indiana Bats from a single maternity

colony hibernate in many different places may aid in spreading this disease.

To date, 11 (15%) of the71 Indiana Bats that we banded in summer have been recovered

at their hibernacula. Rates of recovery of banded bats are typically low (Ellison 2008), and

our success rate is one of the highest ever in terms of bats banded in summer later being

found at distant hibernacula. We attribute this success to a number of factors. First, efforts

of resource agencies to monitor the population of hibernating Indiana Bats every 2 years, in

accordance with the recovery plan for the Indiana Bat (US Fish and Wildlife Service 2007),

ensures that biologists are consistently visiting all major hibernacula across the range of

the species. Second, mass banding of thousands of bats at hibernacula (e.g., Hall 1962) no

longer occurs; consequently, the few banded animals that are present draw the attention of

surveyors. Finally, our bands, unlike many others in use today, are distinctive and provide

information about the bander. We strongly encourage resource personnel to continue recording

information from banded animals during winter. Perhaps 90% of these bats will

soon die from white-nose syndrome (Turner et al. 2011), and the opportunity to gather information

on long-distance movements may be lost forever.

Acknowledgments. We thank V. Brack and L.M. Walker of Environmental Solutions and

Innovations; T. Hemberger and B. Slack of the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife

Resources; and S. Thomas of the US National Park Service, for providing information on

the five bats. We also thank the many members of the Indiana Department of Natural Resources,

Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife

Resources, US Forest Service, US National Park Service, and US Fish and Wildlife

Service, who participated in the winter surveys. M. Schaeffer kindly allowed access to the

Lewisburg Mine. Banding at Palmyra was supported by State Wildlife Grant T-9-T-1, administered

by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and awarded to A. Kurta.

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 20, No. 3

N12

C.D. Rockey, J.P. Stumpf, and A. Kurta

Literature Cited

Brack, V., Jr. 2007. Temperatures and locations used by hibernating bats, including Myotis sodalis

(Indiana Bat), in a limestone mine: Implications for conservation and management. Environmental

Management 40:739–746.

Cryan, P.M. 2011. Wind turbines as landscape impediments to the migratory connectivity of bats.

Environmental Law 41:355–370.

Cryan, P.M., and J.P. Veilleux. 2007. Migration and use of autumn, winter, and spring roosts by

tree bats. Pp. 153–175, In M.J. Lacki, J.P. Hayes, and A. Kurta (Eds.). Bats in Forests. Johns

Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. 329 pp.

Dobony, C.A., A.C. Hicks, K.E. Langwig, R.I. von Linden, J.C. Okoniewski, and R.E. Rainbolt.

2011. Little Brown Myotis persist despite exposure to white-nose syndrome. Journal of Fish

and Wildlife Management 2:190–195.

Dorr, J.A., Jr., and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, Ann

Arbor, MI. 476 pp.

Ellison, L.E., 2008. Summary and analysis of the United States government bat banding program.

United States Geological Survey. Open-File Report 2008-1363:1–117.

Ellison, L.E., 2012. Bats and wind energy: A literature synthesis and annotated bibliography. US

Geological Survey Open-File Report 2012–1110:1–57.

Fleming, T.H., and P. Eby. 2003. Ecology of bat migration. Pp. 156–208, In T. Kunz and M.B.

Fenton (Eds.). Bat Ecology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 798 pp.

Gardner, J.E., and E.A. Cook. 2002. Seasonal and geographic distribution and quantification of potential

summer habitat. Pp. 9–20, In A. Kurta, and J. Kennedy (Eds.). The Indiana Bat: Biology

and management of an endangered species. Bat Conservation International, Austin, TX. 253 pp.

Gardner, J. E., J. D. Garner, and J. E. Hofmann. 1991. Summer roost selection and roosting behavior

of Myotis sodalis (Indiana Bat) in Illinois. Unpublished report, Illinois Natural History

Survey, Champaign, IL.

Gumbert, M.W., J.M. O’Keefe, and J.R. MacGregor. 2002. Roost fidelity in Kentucky. Pp.

143–152, In A. Kurta and J. Kennedy (Eds.). The Indiana Bat: Biology and Management of an

Endangered Species. Bat Conservation International, Austin, TX. 253 pp.

Hall, J.S. 1962. A life history and taxonomic study of the Indiana Bat, Myotis sodalis. Reading

Public Museum and Art Gallery, Scientific Publications 12:1–68.

Kurta, A. 2010. Reproductive timing, distribution, and sex ratios of tree bats in Lower Michigan.

Journal of Mammalogy 91:586–592.

Kurta, A., and S.W. Murray. 2002. Philopatry and migration of banded Indiana Bats and effects of

using radio transmitters. Journal of Mammalogy 83:585–589.

Kurta, A., and H. Rice. 2002. Ecology and management of the Indiana Bat in Michigan. Michigan

Academician 33:361–376.

Kurta, A., S. W. Murray, and D. Miller. 2002. Roost selection and movements across the summer

landscape. Pp. 118–129, In A. Kurta and J. Kennedy (Eds.). The Indiana Bat: Biology and

Management of an Endangered Species. Bat Conservation International, Austin, TX. 253 pp.

Powell, R. L. 1961. Caves of Indiana. Indiana Department of Conservation, Geological Survey,

Circular 8:1–127.

Turner, G.G., D.M. Reeder, and J.T.H. Coleman. 2011. A five-year assessment of mortality and

geographic spread of white-nose syndrome in North American bats and a look to the future.

Bat Research News 52:13–27.

US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Indiana Bat draft recovery plan: First revision. Ft. Snelling,

MN.

US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012a. Endangered Indiana Bat found dead at Ohio wind facility;

steps underway to reduce future mortalities. Available online at http://www.fws.gov/midwest/

News/release.cfm?rid=604. Accessed 12 December 2012.

US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012b. White-nose syndrome. The devastating disease of hibernating

bats in North America. Available online at http://whitenosesyndrome.org/sites/default/files/

resource/white-nose_fact_sheet_9-2012.pdf. Accessed 17 December 2012.

Northeastern Naturalist Notes

N13

2013 Vol. 20, No. 3

C.D. Rockey, J.P. Stumpf, and A. Kurta

Whitaker, J.O., Jr., and V. Brack, Jr. 2002. Distribution and summer ecology in Indiana. Pp. 48–54,

In A. Kurta and J. Kennedy (Eds.). The Indiana Bat: Biology and Management of an Endangered

Species. Bat Conservation International, Austin, TX. 253 pp.

Winhold, L. 2007. Community ecology of bats in southern Lower Michigan, with emphasis on

roost selection by Myotis. Unpubl. M.Sc. Thesis. Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI.

Winhold, L., and A. Kurta. 2006. Aspects of migration by the endangered Indiana Bat (Myotis

sodalis). Bat Research News 47:1–6.

Winhold, L., E. Hough, and A. Kurta. 2005. Long-term fidelity of tree-roosting bats to a home area.

Bat Research News 46:9–10.