N1

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

First Record and Habitat Notes for Cyzicus mexicanus

(Branchiopoda: Spinicaudata) in New Jersey

Elena S. Tartaglia1,* and David Moskowitz2

Abstract - Clam shrimp are small, freshwater branchiopods that inhabit isolated, ephemeral pools—

both natural and anthropogenic. Here we report a new locality for Cyzicus mexicanus (Mexican Clam

Shrimp) in Middlesex County, NJ, that represents the first record of this species in New Jersey and a

range expansion 120 km north of the nearest documented population. The only member of the genus

that has previously been reported in New Jersey is Cyzicus gynecia (Mattox Clam Shrimp). The primary

way that Mexican Clam Shrimp is distinguished from its congener Mattox Clam Shrimp is by

the presence of individuals possessing male reproductive organs known as claspers. Since the only

documented Mattox Clam Shrimp individuals are female, male specimens are indicative of Mexican

Clam Shrimp.

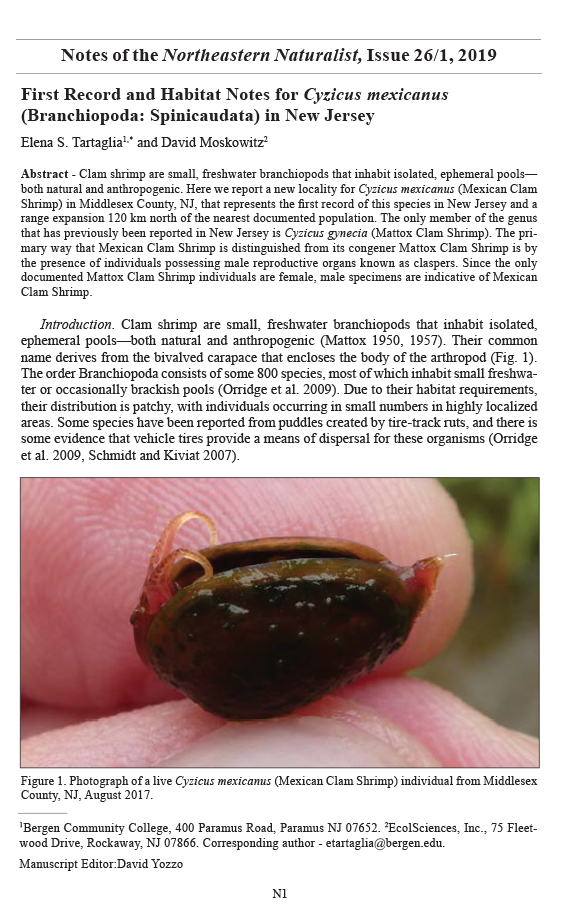

Introduction. Clam shrimp are small, freshwater branchiopods that inhabit isolated,

ephemeral pools—both natural and anthropogenic (Mattox 1950, 1957). Their common

name derives from the bivalved carapace that encloses the body of the arthropod (Fig. 1).

The order Branchiopoda consists of some 800 species, most of which inhabit small freshwater

or occasionally brackish pools (Orridge et al. 2009). Due to their habitat requirements,

their distribution is patchy, with individuals occurring in small numbers in highly localized

areas. Some species have been reported from puddles created by tire-track ruts, and there is

some evidence that vehicle tires provide a means of dispersal for these organisms (Orridge

et al. 2009, Schmidt and Kiviat 2007).

1Bergen Community College, 400 Paramus Road, Paramus NJ 07652. 2EcolSciences, Inc., 75 Fleetwood

Drive, Rockaway, NJ 07866. Corresponding author - etartaglia@bergen.edu.

Manuscript Editor:David Yozzo

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 26/1, 2019

Figure 1. Photograph of a live Cyzicus mexicanus (Mexican Clam Shrimp) individual from Middlesex

County, NJ, August 2017.

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

N2

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

Clam shrimp are found throughout North America, primarily in the west (Smith and

Gola 2001). Those species that do occur east of the Mississippi River are found in highly

localized populations (Smith and Gola 2001, Wolfe 1982). In New Jersey, only 1 species,

Cyzicus gynecia Mattox (Mattox Clam Shrimp), has previously been reported for the state,

from Bergen County in 2007 (Schmidt and Kiviat 2007). Here we report Cyzicus mexicanus

Claus (Mexican Clam Shrimp) from Middlesex County, representing the first record of this

species in New Jersey.

The taxonomy of C. mexicanus (Spinicaudata; Cyzicidae) has been under investigation

for a number of years. Taxonomists are currently working on revisions to this genus, so the

classification of this species may change. Mattox (1939) classified the American taxa, describing

3 North American genera of Cyzicidae – Cyzicus, Caenestheriella, and Eocyzicus.

Most species in these genera are distributed in the central and southwestern areas of the

continent. In North America, the genus Cyzicus currently contains 4 species: C. californicus

Packard (California Clam Shrimp), Mattox Clam Shrimp, Mexican Clam Shrimp, and

C. morsei Packard (Morse Clam Shrimp) (Mattox 1957). Mexican Clam Shrimp and Mattox

Clam Shrimp are the only species in the genus reported east of the Mississippi River.

Mexican Clam Shrimp has the widest distribution in the genus with populations ranging

from Canada to Mexico and as far east as Maryland (Smith and Gola 2001).

Distinguishing among Cyzicus species, particularly between females of Mexican Clam

Shrimp and Mattox Clam Shrimp is extremely difficult. Taxonomists working on revising

the taxonomy of the Spinicaudata (deWaard et al. 2006, Rogers et al. 2012) have evidence

that the taxonomy is complex and that some specimens may be mis-classified (D. Christopher

Rogers, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, pers. comm.), however both Mattox

Clam Shrimp and Mexican Clam Shrimp are currently valid species names.

One major factor can be used to distinguish Mattox Clam Shrimp from Mexican Clam

Shrimp: the former consists entirely of female individuals, with no male individuals ever

collected (Brantner et al. 2013, Emberton 1980, Orridge et al. 2009). A few studies indicate

that female individuals are autodioecious, possessing both male and female reproductive

tissue (Sassaman and Weeks 1993). Brantner et al. (2013), demonstrated this phenomenon

experimentally, using molecular analysis to provide further evidence that Mattox Clam

Shrimp populations consist entirely of hermaphroditic, self-compatible females.

In many Crustacea, the anterior appendages of males are modified as pincer-like claspers

for grasping females during sexual reproduction (Thorp and Covich 2010), and Cyzicus

is no exception: individuals are sexually dimorphic with male individuals possessing distinctive

claspers that are absent in females (Fig. 2). Here we present evidence for the first

record of Mexican Clam Shrimp in New Jersey.

Study area. Middlesex County is a highly suburbanized county located in the Piedmont

region of central New Jersey (Robichaud and Buell 1974). The landscape is a mix of undeveloped

lands, agriculture, and low- to high-density development. Power line right-of-ways

(ROWs) also cross the county in many places. Our study area was within a ROW in South

Brunswick Township (Fig. 3). The ROW is approximately 45 m wide and is regularly maintained

to prevent woody vegetation from growing taller than 3 m. The ROW is bisected by

an old trolley line that was constructed on fill material in the early part of the 20th century

and is elevated ~1–2 m above the surrounding area. Other than this old, filled track-base, no

evidence of the trolley line remains. This track base serves as a road for the power company

to regularly access the ROW and also appears to be used by all-terrain vehicles (ATVs).

Due to rainfall preceding and during the study, the access road was lined with puddles

that are likely only intermittently filled with water during wetter seasons and following

N3

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

Figure 2. Diagram of a male

Cyzicus mexicanus (Mexican

Clam Shrimp) with the left valve

removed showing reproductive

claspers possessed by male individuals.

Figure adapted from

Wolfe 1982.

Figure 3. Photograph of the

ROW habitat showing a pool

occupied by clam shrimp as well

as representative vegetation and

tree cover.

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

N4

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

precipitation. Observations made during the summer and fall suggest that only the largest

pools hold water during extended dry periods. In this portion of the ROW, we identified 24

distinct pools with the potential to contain clam shrimp.

Field and laboratory methods. We first observed clam shrimp in the field on 17 August

2017 and collected our original specimens on 21 August 2017. We visually assessed pools

in the ROW for the presence of clam shrimp, netted specimens with a small dipnet, and

immediately preserved them in 91% isopropyl alcohol. For pools containing specimens,

we also measured pool size and depth with a standard 60-m tape and pH (ExTech ExStick,

model PH100), and recorded dominant vegetation in and around the pools. We noted other

animal taxa, such as amphibians and invertebrates, although we did not systematically survey

them. In the lab, we examined specimens using a dissecting microscope and identified

them to genus using the description in Mattox (1957). We followed Smith and Gola (2001)

to make additional species comparisons.

On 14 June, 2018, M. Popin (EcolSciences, Inc. Rockaway, NJ, pers. comm.) observed

potential mating clam shrimp in puddles within the original ROW, ~1.6 km to the west of

the 2017 location. On the same day, D. Moskowitz collected 4 mating pairs of clam shrimp

from this location (Fig. 4). On 16 June, 2018, D. Moskowitz collected an additional 3 mating

pairs of clam shrimp from the original clam shrimp puddles discovered in 2017. We

identified these specimens in the lab in the same manner as the original set of specimens.

Results. In 2017, the ROW contained 24 pools, from which we collected 8 individuals,

although more specimens were present in the pools. We collected only a minimal number of

clam shrimp for identification purposes due to the uncertain status of their rarity. Although

we made no attempt to estimate the population, in part due to the difficulty of seeing individuals

in the pools, and the desire to be as un-intrusive to the clam shrimp and habitat as

possible, there were certainly more individuals present than we collected.

Clam shrimp were present in 4 of the 24 pools surveyed. Pools containing clam shrimp

were shallow (less than 0.5 m deep); average dimensions were 7.8 m long x 3.6 m wide, and the

Figure 4. Photograph of a mating pair of Cyzicus mexicanus (Mexican Clam Shrimp), June 2018.

N5

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

bottom substrate was gravel fill covered in thin, easily suspended silt. Water pH of all of the

pools was approximately neutral (6.7–7.4 standard units; Table 1). The pools were located

in an actively maintained powerline ROW; there was no tree cover or shading, and all pools

were exposed to direct sunlight. Vegetation in and around the pools was a mix of native

and non-native herbs characteristic of early-successional wet habitats, including Eleocharis

obtusa Schult. (Blunt Spikerush), Persicaria hydropiperoides Small (Swamp Smartweed),

Persicaria arifolia Haraldson (Halberd-leaved Smartweed), Sagittaria cuneata Sheld.

(Arumleaf Arrowhead), Leersia oryzoides Sw. (Rice Cutgrass), Solidago canadensis L.

(Canada Goldenrod), Hydrocharis morsus-ranae L. (Frogbit), and Cyperus sp. (nutsedge)

The pools also contained aquatic beetles, odonate larvae and several species of tadpoles, including

Anaxyrus americanus Holbrook (American Toad), Hyla versicolor LeConte (Gray

Tree Frog), and Lithobates palustris LeConte (Pickerel Frog).

Table 1. Characteristics of pools containing clam shrimp in Middlesex County NJ, August 2017.

Length (m) Width (m) pH Depth (m)

Pool 1 11.0 4.3 6.9 0.48

Pool 2 6.0 3.7 6.7 0.44

Pool 3 4.7 3.8 7.4 0.39

Pool 4 9.6 2.4 7.2 0.42

Figure 5. Photograph

of a Cyzicus

mexicanus (Mexican

Clam Shrimp)

specimen with both

valves removed. Arrow

denotes position

of reproductive

claspers indicative

of males.

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

N6

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

All 8 of the original specimens collected possessed characteristics consistent with the

genus Cyzicus. Seven specimens were female and 1 specimen had claspers indicative of

males (Fig. 5). Due to the morphological characteristics, we determined that our specimens

matched descriptions for Mexican Clam Shrimp: dark carapace color, elongated shape,

average of 22 carapace rings, mean length of 12.4 mm, mean height of 8.1 mm, and umbos

positioned in the first 1/8–2/8 of the carapace length. When we dissected the mating pairs

collected in June 2018, we found the expected 1:1 male to female ratio at both locations.

Each female also carried eggs (Fig. 6).

Discussion. Clam shrimp are known to inhabit small, ephemeral, freshwater pools and

our surveyed ROW represents a typical habitat for these organisms. The impermanent nature

of these pools generally reduces the presence of aquatic predators, making them safe,

if unpredictable, habitats for small organisms. Clam shrimp produce eggs that are tolerant

of heat, cold, and desiccation by undergoing periods of dormancy, making them well-suited

to ephemeral habitats (Belk and Belk 1975, Mattox and Velardo 1950).

The ephemeral nature of pools inhabited by clam shrimp is in part driven by local precipitation.

The precipitation average for central New Jersey in the 6 months preceding the

discovery of the clam shrimp (February–July 2017) was slightly above normal at 62.79

cm (24.72 in) compared to the 30-y average of 62.28 cm (24.52 in). In the month leading

up to our initial discovery, July through August of 2017, rain occurred on 15 out of 30

days (ONJSC 2018).

Figure 6. Photograph of a female Cyzicus mexicanus (Mexican Clam Shrimp) specimen with eggs.

N7

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

Although the habitat is typical, the question of dispersal mechanisms employed by such

small organisms between patchily distributed pools remains speculative, particularly for

the under-studied clam shrimp. Schmidt and Kiviat (2007) hypothesized several dispersal

methods including eggs dispersed via wind during dry periods or via mammal fur, bird

feathers, or animal feet. Procyon lotor (L.) (Raccoon) and Anatidae spp. (ducks), which

visit puddles to forage, are excellent candidates for clam-shrimp–dispersal vectors, though

few studies have experimentally examined this phenomenon (Schmidt and Kiviat 2007).

Long-distance dispersal within the gastrointestinal tract of organisms is another possibility,

and Proctor et al. (1967) documented this phenomenon for the related branchiopod crustacean,

Artemia, which can maintain viability after passing through the guts of birds. Vehicles

may harbor eggs or adults on tires (Orridge et al. 2009), contributing to dispersal between

or within sites. In our surveyed ROW, maintenance vehicles and ATVs created the ruts that

became the pools from which we collected our specimens.

Though Mattox Clamp Shrimp and Mexican Clam Shrimp are both known to occur east

of the Mississippi River, and Mattox Clamp Shrimp has been previously reported in New

Jersey, we report our finding as the first record for Mexican Clam Shrimp in New Jersey

and propose a range extension for the species. This finding represents the first new record

for the genus Cyzicus in New Jersey in a decade (Schmidt and Kiviat 2007). The nearest

reports of populations of Mexican Clam Shrimp are in eastern Pennsylvania (Wolfe 1982).

Our South Brunswick, NJ, population extends the documented range for this species ~120

km east of the closest documented populations.

Acknowledgments. We thank D. Grossmueller for his review of the paper, M. Popin for assistance

with fieldwork, J. Smalley for laboratory assistance, L. Struwe for taxonomic guidance, and 2 anonymous

reviewers for their help in preparing this manuscript.

Literature Cited

Belk, D., and M.S. Belk. 1975. Hatching temperatures and new distributional records for Caenestheriella

setosa (Crustacea, Conchostraca). Southwestern Naturalist 20:409–411.

Brantner, J.S., D.W. Ott, R.J. Duff, J.I. Orridge, J.R Waldman, and S.C. Weeks. 2013. Evidence of

selfing hermaphroditism in the clam shrimp Cyzicus gynecia (Branchiopoda: Spinicaudata). Journal

of Crustacean Biology 33:184–190.

deWaard, J.R., V. Sacherova, M.E.A. Cristescu, E.A. Remigio, T.J. Crease, and P.D.N Hebert. 2006.

Probing the relationships of the branchiopod crustaceans. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution

39:491–502.

Emberton, K.C. 1980. Brief note: Ecology of a fall population of the clam shrimp Caenestheriella

gynecia Mattox (Crustacea: Conchostraca). The Ohio Journal of Science 80:156–159.

Mattox, N.T. 1939. Description of 2 new species of the genus Eulimnadia and notes on the other Phyllopoda

of Illinois. American Midland Naturalist 22:642–653.

Mattox, N.T. 1950. Notes on the life history and description of a new species of Conchostracan Phyllopod,

Caenestheriella gynecia. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 69:50–53.

Mattox, N.T. 1957. A new estheriid conchostracan with a review of the other North American forms.

American Midland Naturalist 58:367–377.

Mattox, N.T., and J.T. Velardo. 1950. Effect of temperature on the development of the eggs of a conchostracan

phyllopod, Caenestheriella gynecia. Ecology 31:497–506.

Office of the New Jersey State Climatologist (ONJSC). 2018. Monthly climate tables. Available

online at http://climate.rutgers.edu/stateclim_v1/nclimdiv/index.php?stn=NJ01&elem=pcpn. Accessed

11 May 2018.

Orridge, J., J. Waldman, and R.E. Schmidt. 2009. Genetic, morphological, and ecological relationships

among Hudson Valley populations of the clam shrimp, Caenestheriella gynecia. Section VI

in S.H. Fernald and D. Yozzo (Eds.). Final Reports of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program,

2008. Hudson River Foundation, New York, NY. 31 pp.

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

N8

E.S. Tartaglia and D. Moskowitz

Proctor, V.W., C.R. Malone, and V.L. DeVlaming. 1967. Dispersal of aquatic organisms: Viability of

disseminules recovered from the intestinal tract of captive Kil ldeer. Ecology 48:672–676.

Robichaud, B., and M.F. Buell. 1974. Vegetation of New Jersey. Rutgers University Press, New

Brunswick, NJ. 340 pp.

Rogers, D.C., N. Rabet, and S.C. Weeks. Revision of the extant genera of Limnadiidae (Branchiopoda:

Spinicaudata). Journal of Crustacean Biology 32:827–842.

Sassaman, C., and S.C. Weeks. 1993. The genetic mechanism of sex determination in the conchostracan

shrimp Eulimnadia texana. American Naturalist 141:314–328.

Schmidt, R.E., and E. Kiviat. 2007. State records and habitat of clam shrimp, Caenestheriella gynecia

(Crustacea: Conchostraca), in New York and New Jersey. Canadian Field-Naturalist 121:128–132.

Smith, D.G., and A.A. Gola. 2001. The discovery of Caenestheriella gynecia (Branchiopoda, Cyzicidae)

in New England, with ecological and systematic notes. Nort heastern Naturalist 8:443–454.

Thorp, J.H., and A.P Covich. 2010. Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates,

3rd Edition. Academic Press, New York, NY. 1021 pp.

Wolfe, A.F., 1982. Distribution of Cyzicus mexicanus (Conchostraca: Crustacea) in Lebanon County,

Pennsylvania. Proceedings of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science 56:36–38.