2016 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 15, No. 4

N44

W.F. Haslam, R.A. Rowe, and J.L. Phillips

A Mixed Brood Following Usurpation of a Carolina Chickadee

Nest by Tree Swallows

Wynn F. Haslam1, Richard A. Rowe1,*, and J. Luke Phillips1

Abstract - Naturally occurring mixed species broods are uncommon but can occur due to nest parasitism,

and in rare cases, due to usurpation. We report on a mixed brood resulting from a pair of Tree

Swallows usurping a Carolina Chickadee nest. The chickadee nest was constructed in a nest box, and

1 egg was laid prior to usurpation. This egg, in addition to the clutch of swallow eggs, was incubated,

hatched, and fed by the adult swallows. The chickadee nestling grew and appeared to be healthy at

6–7 days of age, but was approximately 50% smaller than its nest mates at that time. The chickadee

died after 8 days, most likely due to starvation. The remaining Tree Swallow nestlings were reared to

fledging by the adults.

Introduction. The presence of eggs or nestlings of different bird species in the same nest

is unusual. Typically, mixed broods are the result of obligate brood parasitism (Payne 1977).

Facultative brood parasitism can occur as a result of limited nesting resources (Barrientos

et al. 2015, Petrassi et al. 1998) and, in rare cases, with species not associated with nest

parasitism (Neal and Rolland 2015, Peer 2010; see Yom-Tov 2001 for a review). Naturally

occurring, but accidental, mixed nests due to usurpations have been reported in several

species (Austin et al. 2009, Barrientos et al. 2015, Dolenec 2002, Golawski 2007, Petrassi

et al. 1998, Samplonius and Both 2013, Suzuki and Tsuchiya 2010). We provide the first

report of a naturally occurring mixed brood of a Poecile carolinensis (Audubon) (Carolina

Chickadee; hereafter Chickadee) and Tachycineta bicolor (Vieillot) (Tree Swallow; hereafter

Swallow) due to usurpation of a Chickadee nest by Swallows.

Field Site. Observations were made during April and May of 2016 at the Virginia

Military Institute Biology Department’s Field Research Site (37°46'45.09"N,

79°23'30.51"W) located approximately 4 km east of Lexington in west-central VA. The

site is a 9-ha hayfield with 30 nest boxes (14 cm x 14 cm x 25 cm, opening 16.5 cm above

floor) placed in a grid to attract Swallows. All nest boxes were mounted on poles with antipredator

baffles (stove pipe, 20.5 cm x 61 cm). Even though our focus was on Swallow

nests, we monitored all nest boxes during the breeding season. Nest status (construction,

incubation of eggs, and rearing of young) was checked twice a week, except daily during

the egg-laying phase and near expected time of hatching to establish onset of incubation

and the nestling phase. The nest-checking protocol used in this study was reviewed by

the Animal Subjects Committee at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI ASC permit number

2013-02). None of the birds in this study were marked.

Observations. A routine check of nest boxes on 12 April 2016 found no bird activity at

nest box 25 (NB 25). On 16 April, we discovered a nearly complete Chickadee nest in NB

25, but a pair of Swallows actively defended the nest box (alarm calls and swooping). We

checked the nest box on 19 April, at which time the Chickadee nest contained mammal fur,

and again, the Swallows were showing defense behavior. During our nest box check on

21 April, we found the beginnings of a Swallow nest being built on top of the Chickadee

nest. At this point, we assumed that the Swallows had usurped the nest and displaced the

1Department of Biology, Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, VA 24450. *Corresponding author -

rowera@vmi.edu.

Manuscript Editor: Frank Moore

Notes of the Southeastern Naturalist, Issue 15/4, 2016

N45

2016 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 15, No. 4

W.F. Haslam, R.A. Rowe, and J.L. Phillips

Chickadees. Two days later (23 April), we observed a Chickadee exiting the nest box even

though the Swallows actively defended it when we approached. The Swallows had added

some additional grass to the nest box, creating a small but incomplete nest cup on top of the

Chickadee nest. This Swallow nest was not typical; it was not the large, grass nest with a

distinct cup that was seen in other nest boxes at our field site. On 26 April, 1 Chickadee egg

was found in the nest cup. On 28 April, the Swallows began adding feathers to the nest, an

indication that egg laying was about to commence. On 30 April, the check of NB 25 showed

1 Chickadee egg and 1 Swallow egg present. Subsequently, 1 Swallow egg was added to the

nest each day, so that on 5 May the clutch contained 6 Swallow eggs and 1 Chickadee egg.

We estimated that the Swallows began incubating on either 4 or 5 May.

The average incubation time for Swallows at our field site was 13 days from the laying

of the last egg, and we expected that Swallow eggs would begin hatching on 18 May. An

inspection of the eggs on 12 May showed that 5 of the 6 Swallow eggs were fertile and that

the Chickadee egg was fertile. The Chickadee egg hatched on 17 May, and 2 of the Swallow

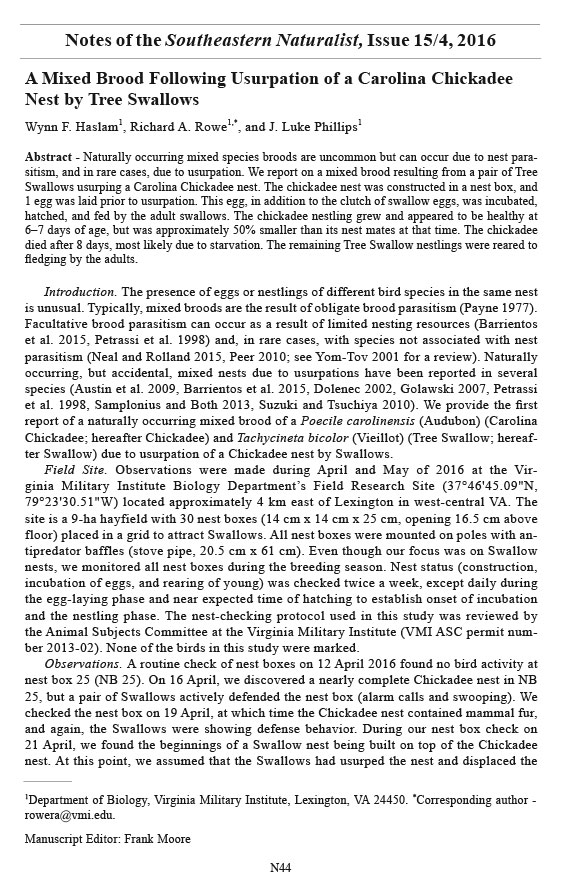

eggs hatched on 18 May. Our check of the nest on 19 May showed that there were 4 Swallow

nestlings, the Chickadee nestling, and 2 remaining eggs (Fig. 1). We checked NB 25

on 22 May, at which time all 5 nestlings were present, were visibly larger, and exhibited an

Figure 1. Photograph of the Tree Swallow brood with Carolina Chickadee nestling. The Chickadee

is 2 days post-hatching. The Tree Swallow nestlings are 0–1 day post-hatching. (Photograph by R.A.

Rowe.)

2016 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 15, No. 4

N46

W.F. Haslam, R.A. Rowe, and J.L. Phillips

active gapping response, indicating that the Chickadee nestling was healthy and being fed

by the Swallow adults. On 22 May, there was only 1 Swallow egg (infertile egg) in the nest.

The remaining Swallow egg had hatched, and this nestling being several days younger and

thus much smaller than its nest mates died. When we checked on 23 May, the Chickadee

nestling was noticeably smaller than the Swallow nest mates (Fig. 2), but it appeared to be

healthy and was larger than at the time of the previous nest check. We observed NB 25 on

26 May and found only 4 Swallow nestlings. The Chickadee nestling was not visible in the

nest box. After the Swallow nestlings fledged on 6 June, we examined the nest box contents

and found the Chickadee nestling’s carcass in the debris of the nest. While we do not know

the cause of death, we suspect that it died of starvation.

Discussion. Naturally occurring mixed broods that are not the result of parasitism are rare.

In many cases, the heterospecific egg fails to hatch due differences in egg size, with smaller

eggs having less contact with the brood patch and thus developing slower or not at all (Barrientos

et al. 2015). Chickadee eggs are smaller (mean size of 14.8 mm x 11.5 mm and 1.04 g;

Mostrom et al. 2002) than Swallow eggs (mean size of 18.7 cm x 13.2 cm and 1.9 g; Winkler et

al. 2011). Even though the Chickadee egg was noticeably smaller and differed in color from the

Swallow eggs, the adult Swallows incubated the egg rather than removing it from the nest. At

hatching, the Chickadee nestling was smaller than the Swallows, but the size differential was

not substantial. At 6 days old (d.o.) (Fig. 2), the Swallow nestlings (mean mass at 6 d.o. = 11 g,

mean mass at 8 d.o. = 16 g; Zach and Mayoh 1982) appeared to be nearly twice the size of the

Chickadee nestling (similar data are not available for Carolina Chickadees, but using data from

the similar-sized Poecile rufescens (Townsend) [Chestnut-backed Chickadee], the nestling

likely weighed about 5 g at 6 d.o.; Gaddis and Corkran 2008). By 6 d.o., Swallow nestlings

would be equal to or greater in body mass than an adult Chickadee (9.8–11.0 g; Mostrom et

Figure 2. Photograph of the Tree Swallow brood with the Carolina Chickadee nestling. The Chickadee

nestling is 7 days post-hatching. The 4 Swallow nestlings are 5–6 days post-hatching. (Photograph

by R.A. Rowe.)

N47

2016 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 15, No. 4

W.F. Haslam, R.A. Rowe, and J.L. Phillips

al. 2002). Both Zach and Mayoh (1982) and Austin et al. (2009) show that Swallows are in the

rapid growth phase at these ages, and approach adult weight (20–21 g; Zach and Mayoh 1982)

at 13 days of age. We suspect that between nest checks on 23 May and 26 May, the Chickadee

nestling was at such a size disadvantage that either it could not compete for food and died from

starvation or it was crushed by the larger Swallow nestlings. In a situation similar to our study,

Austin et al. (2009) report on the usurpation of a Troglodytes aedon (Vieillot) (House Wren)

nest by Tree Swallows, and the subsequent incubation and rearing of the nestlings. Two House

Wren nestlings hatched and survived for 6 and 13 days, respectively, until they died of apparent

starvation. Austin et al. (2009) regularly weighed the nestlings and noted that the House Wren

growth rates were below normal. Adult House Wrens (10–12 g; Austin et al. 2009) are the same

size as Chickadees. The House Wrens showed initial growth and development, but as the House

Wrens and Swallows entered the rapid growth phase, the differences in body size led to a decrease

in ability to compete for food and ultimately death due to starvation.

Some mixed broods do survive to fledging. Suzuki and Tsuchiya (2010) report the rearing

and fledging of a mixed brood (1 Parus major (L.) [Great Tit] and 5 Poecile varius (Temminck

& Schlegel) [Varied Tit]) that occurred as a result of usurpation by the Varied Tits.

A pair of Sitta europaea (L.) (Nuthatch) usurped a Great Tit nest, incubated the single egg

in the nest, and reared the Great Tit to fledging (Dolenec 2002). Uniquely, Samplonius and

Both (2013) report on a mixed brood that contained 3 species (Ficedula hypoleuca (Pallas)

[Pied Flycatcher], Cyanistes caeruleus (L.) [Blue Tit], and Great Tits) that resulted from

2 usurpation events. The Great Tits successfully reared the nest to fledging. Petrassi et al.

(1998) report on several instances of Great Tits usurping Blue Tit nests and rearing the mixed

broods to fledging. Robinson et al. (2005) report on nest sharing by Sitta canadensis (L.)

(Red-breasted Nuthatch) and Poecile gambeli (Ridgway) (Mountain Chickadee) that resulted

in fledging of nestlings from both species. This mixed nest did not appear to be the result

of usurpation because both species were observed feeding the mixed brood. In these cases,

the mixed broods were from similar species or similarly sized birds and as a result competition

between nestlings did not result in starvation of the smaller nestling. Also, it is likely

that food choice and provisioning by the adults met the dietary needs of the nestlings.

Secondary cavity nesters such as Tree Swallows, Carolina Chickadees, and Sialia sialis

(L.) (Eastern Bluebird) can be limited by the availability of suitable nesting sites (Gowaty

and Plissner 2015, Holroyd 1975, Mostrom et al. 2002). The presence of artificial cavities

(nest boxes) in areas where natural cavities are limited creates a situation in which competition

for nest boxes can lead to usurpation (Barientos et al. 2015, Petrassi et al. 1998).

We are confident that the presence of the Chickadee egg in the nest was due to usurpation

of the Chickadee nest by the Swallows and not the result of nest parasitism by a female

Chickadee because the Chickadee nest was constructed prior to construction of the Swallow

nest. An adjacent nest box (NB 26) that was 62 m away contained a Chickadee nest that had

completed a clutch of 5 eggs on 21 April, 5 days prior to the egg appearing in NB 25. It is

unlikely that the female from NB 26 produced an egg 5 days into incubation and parasitized

another Chickadee nest. At the time of the usurpation event (21 April), 67% of the nest

boxes in the grid were occupied (11 by Swallows, 6 by Eastern Bluebirds, 2 by Chickadees

and 1 by a Baeolophus bicolor (L.) [Tufted Titmouse]) and 33% of the nest boxes were

open. By 23 April, 74% of the nest boxes were claimed. The usurping pair of Swallows

consisted of a male (after-hatch-year plumage) and, a second-year female (ascertained by

plumage characteristics; Hussell 1983). It is unclear to us why this pair chose to usurp the

Chickadee nest rather than select an unoccupied nest box. This pair may have been less aggressive

or experienced and could not compete with other Swallows for nest boxes.

2016 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 15, No. 4

N48

W.F. Haslam, R.A. Rowe, and J.L. Phillips

The mixed brood described in this report appears to have been the result of nest

usurpation and subsequent incubation and rearing of the heterospecific nestling. While the

Chickadee nestling was fed by the host Swallows, it is likely that a combination of differences

in body size between the Chickadee and Swallow nestlings, prey types presented by

the adults, and feeding rates resulted in death of the Chickadee nestling. Success of a mixed

brood is dependent on similarity between the species in development rates, body sizes, and

food requirements. Our study and that of Austin et al. (2009) are the only 2 reports of Tree

Swallows rearing heterospecific nestlings. In both of these cases, the heterospecific nestlings

were from smaller species and died prior to fledging.

Acknowledgments. We would like to thank Drs. Anne Alerding and Paul Moosman and

2 anonymous reviewers for their comments on this manuscript. This study was funded in

part through the VMI Biology Department’s Carroll Fund, VMI’s Jackson-Hope Fund, VMI

SURI funding, and a grant from the North American Bluebird Society.

Literature Cited

Austin, S.H., T.R. Robinson, W.D. Robinson, and N.A. Chartier. 2009. A natural experiment: Heterospecific

cross-fostering of House Wrens (Troglodytes aedon) by Tree Swallows (Tachycineta

bicolor). American Midland Naturalist 162:382–387.

Barientos, R., J. Bueno-Enciso, E. Serrano-Davies, and J.J. Sanz. 2015. Facultative interspecific

brood parasitism in Tits: A last resort to coping with nest-hole Shortage. Behavioral Ecology and

Sociobiology 69:1603–1615.

Dolenec, Z. 2002. A mixed brood of Nuthatch (Sitta europaea) and Great Tit (Parus major) species.

Natura Croatica 11:103–105.

Gaddis, P.K., and C.C. Corkran. 2008. Reproductive biology of the Chestnut-backed Chickadee (Poecile

rufescens) in Northwestern Oregon. Northwestern Naturalist 89:152–163.

Golawski, A. 2007. A mixed clutch of the Red-backed Shrike, Lanius collorio, and the Song Thrush,

Turdus philomelos. Ornis Svecica 17:100–101.

Gowaty, P.A., and J.H. Plissner. 2015. Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis). No. 381, In A. Poole (Ed.).

The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. Available online

at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu.bnaproxy.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/381doi:10.2173/bna.381.

Accessed 15 June 2016.

Holroyd, G.L. 1975. Nest-site availability as a factor limiting population size of swallows. Canadian

Field-Naturalist 89:60–64.

Hussell, D.J.T. 1983. Age and plumage color in female Tree Swallows. Journal of Field Ornithology

54:312–318.

Mostrom, A.M., R.L. Curry, and B. Lohr. 2002. Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis). No. 636,

In A. Poole (Ed.). The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY.

Available online at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu.bnaproxy.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/636. Accessed

10 June 2016.

Neal, J.A., and V. Rolland. 2015. A potential case of brood parasitism by Eastern Bluebirds on House

Sparrows. Southeastern Naturalist 14:31–34.

Payne, R.B. 1977. The ecology of brood parasitism in birds. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics

8:1–28.

Peer, B.D. 2010. Conspecific brood parasitism by the Dickcissel. Wilson Journal of Ornithology

122:186–187.

Petrassi, F., A. Sorace, F. Tanda, and C. Consiglio. 1998. Mixed clutches of Blue Tits, Parus caeruleus,

and Great Tits, Parus major, in nest boxes in Central Italy. Ornis Svecica 8:49–52.

Robinson, P.A., A.R. Norris, and K. Martin. 2005. Interspecific nest sharing by Red-breasted Nuthatch

and Mountain Chickadee. Wilson Bulletin 117:400–402.

Samplonius, J.M., and C. Both. 2013. A case of a three species mixed brood after two interspecific

nest takeovers. Ardea 102:105–107.

N49

2016 Southeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 15, No. 4

W.F. Haslam, R.A. Rowe, and J.L. Phillips

Suzuki, T.N., and Y. Tsuchiya. 2010. Feeding a foreign chick: A case of a mixed brood of two Tit species.

Wilson Journal of Ornithology 122:618–620.

Winkler, D.W., K.K. Hallinger, D.R. Ardia, R.J. Robertson, B.J. Stutchbury and R.R. Cohen. 2011.

Tree Swallow (Tachycineta bicolor). No. 11, In A. Poole (Ed.). The Birds of North America

Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. Available online at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu.

bnaproxy.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/011doi:10.2173/bna.11. Accessed 10 June 2016.

Yom-tov, Y. 2001. An updated list and some comments on the occurrence of intraspecific nest parasitism

in birds. Ibis 143:133–143.

Zach, R., and E.R. Mayoh. 1982. Weight and feather growth of nestling Tree Swallows. Canadian

Journal of Zoology 60:1080–1090.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Southeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within the southeastern United States. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.