Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Current Issue: Vol. 30 (3)

Check out NENA's latest Monograph:

Monograph 22

3200006Notes of the NortNhOeRNaTHosrEttheAeSraTnsEte RrNnN NaNatAtuuTrUraaRliAsltiLsIStT, Issue 14/2,V 21o03l.( 0114)7:,3 N9–o4. 22

Xanthoria parietina, a Coastal Lichen, Rediscovered in Ontario

Irwin M. Brodo1,*, Chris Lewis2, and Brian Craig3,4

Abstract - Xanthoria parietina, a conspicuous orange foliose lichen, has been doubtfully

recorded as part of the Ontario lichen flora because the previous documented reports were very

old (1868 and 1917) and it had never been reported since. Here, we document a number of new

sightings, all in southern Ontario. A previous report of this lichen from “Longulac” that was

interpreted as Long Lake in Frontenac County is corrected to Longlac in the Thunder Bay

District, and the specimen proved to be Xanthomendoza hasseana. A search for the lichen

around Belleville, one of the original localities, proved fruitless. It is still not clear whether the

new sightings of Xanthoria parietina represent a reintroduction of this coastal species to the

inland sites, or whether the lichen has persisted in southern Ontario for almost 140 years, but

was never reported. Substrate enrichment (eutrophication due to agricultural activity) in the

region is one explanation for the spread of the lichen in southern Ontario.

Introduction. Xanthoria parietina (L.) Th. Fr., as can be surmised by its vernacular

name, “the maritime sunburst lichen,” was considered to be narrowly confined to

coastal areas in North America, although widespread in the rest of the world (Hinds

1995, Lindblom 1997). The distribution map in Brodo et al. (2001) shows it to occur

from the southeastern corner of Pennsylvania to Newfoundland in the east, as well as

in a small area of coastal Texas, with scattered populations in coastal California,

Oregon, Washington, and southwestern British Columbia. Although a specimen of X.

parietina was known to us from southern Ontario (Belleville, “On trunks, very

common,” Macoun, 533(42), Aug. 17, 1868 [National Herbarium of Canada

(CANL)]), it was regarded to be so questionable (perhaps mislabeled) that it was not

even mentioned in a treatment of the lichens of southern Ontario (Wong and Brodo

1992). In her monograph of the North American species of Xanthoria, however,

Lindblom (1997) reported seeing a second specimen from Ontario at the Smithsonian

Institution (US). It is from “H.B. Post, Longulac, Long Lake,” collected by G.K.

Jennings and O.E. Jennings in July1917. In the absence of any such locality name,

current or historic, in Canadian gazetteers, a guess was made that the locality was

actually “Long Lake” in Frontenac County of southern Ontario and was mapped as

such by Lindblom. Nevertheless, because the species had not been seen in recent

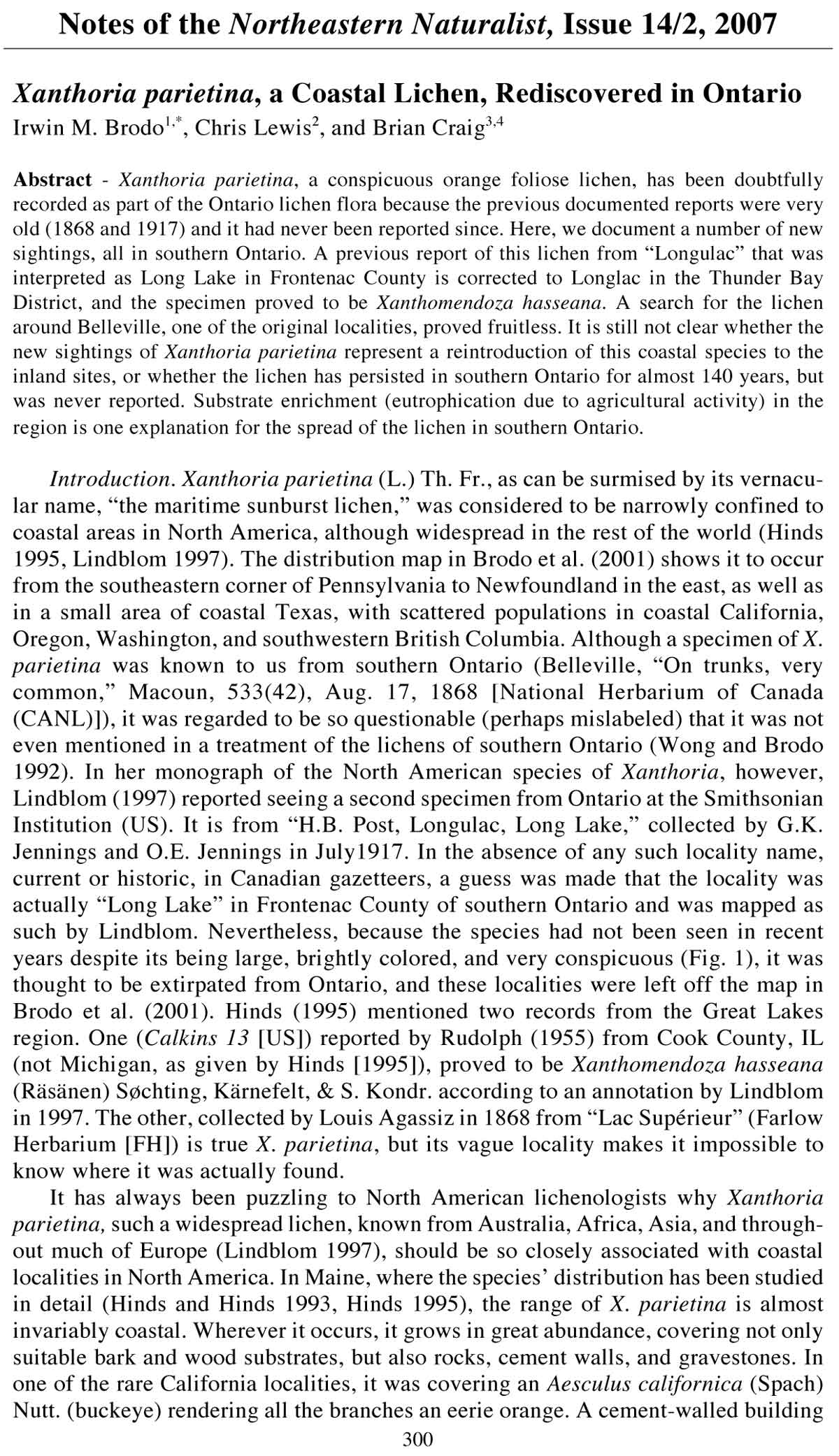

years despite its being large, brightly colored, and very conspicuous (Fig. 1), it was

thought to be extirpated from Ontario, and these localities were left off the map in

Brodo et al. (2001). Hinds (1995) mentioned two records from the Great Lakes

region. One (Calkins 13 [US]) reported by Rudolph (1955) from Cook County, IL

(not Michigan, as given by Hinds [1995]), proved to be Xanthomendoza hasseana

(Räsänen) Søchting, Kärnefelt, & S. Kondr. according to an annotation by Lindblom

in 1997. The other, collected by Louis Agassiz in 1868 from “Lac Supérieur” (Farlow

Herbarium [FH]) is true X. parietina, but its vague locality makes it impossible to

know where it was actually found.

It has always been puzzling to North American lichenologists why Xanthoria

parietina, such a widespread lichen, known from Australia, Africa, Asia, and throughout

much of Europe (Lindblom 1997), should be so closely associated with coastal

localities in North America. In Maine, where the species’ distribution has been studied

in detail (Hinds and Hinds 1993, Hinds 1995), the range of X. parietina is almost

invariably coastal. Wherever it occurs, it grows in great abundance, covering not only

suitable bark and wood substrates, but also rocks, cement walls, and gravestones. In

one of the rare California localities, it was covering an Aesculus californica (Spach)

Nutt. (buckeye) rendering all the branches an eerie orange. A cement-walled building

300

2007 Notes 301

in Martha’s Vineyand, MA, was similarly covered (Sharnoff and Sharnoff 1997).

McCune (2003) also mentions its great abundance in a newly discovered and rare

locality in Oregon. This is not a lichen that is easy to overlook, and yet, despite the

considerable collecting efforts of observant naturalists and collectors such as Roland

Beschel, Roy Cain, John Krug, Rupert Warren, and Pak Yau Wong, not to mention

John Macoun, this lichen has been represented in southern Ontario in only a single

locality based on specimens collected almost 140 years ago, and somewhere in the

western Great Lakes region based on a specimen over 150 years old.

Observations. In the process of studying urban lichens as part of a pilot project by

the Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network (EMAN) using lichens as biological

indicators of air quality in southern Ontario, a small, rather depauperate specimen

of X. parietina was discovered in the University of Guelph Arboretum by B. Craig

(Fig. 1d). Healthier specimens were collected by Craig north of Dunnville and at the

Canada Centre for Inland Waters in Burlington (Fig. 1b). Independently, C. Lewis

found excellent specimens of this species north of Craig’s discoveries: in Hanover

(Fig. 1a), Paisley (Fig. 1c), Arthur, and elsewhere in the region (Appendix 1). The most

extraordinary occurrence was near Orangeville in Dufferin County, where X. parietina

occurred along a drainage ditch, almost entirely covering trees of several tree species,

especially Acer negundo L. (Manitoba maple), but also Fraxinus americana L. (white

Figure 1. Xanthoria parietina specimens from southern Ontario: a. Paisley, b. Burlington,

c. Hanover; d. Guelph. Scale = 1 cm in all photos.

302 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 14, No. 2

ash) and Salix sp. (willow). Most recently, Lewis discovered some good colonies of X.

parietina growing on Acer negundo near a creek just east of Bowmanville

(Clarington). These localities are mapped in Figure 2.

From Figure 2, one might suspect that the species occurs all over southwestern

Ontario, but field investigations by Lewis northwest of Paisley into Port Elgin and

Southampton did not yield sightings, nor did trips to Owen Sound and Chatsworth.

Brodo also sought it without success on the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island in

2005. In Brodo’s resurvey of the Belleville region in 2006, Xanthoria parietina was

not seen, although Xanthomendoza fallax (Hepp ex Arnold) Søchting, Kärnefelt & S.

Kondr. and, to a lesser extent, Xanthomendoza ulophyllodes (Räsänen) Søchting,

Kärnefelt & S. Kondr. were found in abundance on a variety of deciduous trees and

lignum. The most recent discoveries of Xanthoria parietina in Reaboro and just east of

Bowmanville, however, extend the range eastward towards Belleville. The striking

NW–SE alignment of localities between Dunnville and Paisley may well be an artifact

of collecting efforts in that corridor, although it somewhat approximates the location of

the Niagara Escarpment, and almost all the localities fall within the Silurian dolomite

belt between the Bruce Peninsula and Niagara Falls (Fig. 2).

The Jennings and Jennings specimen labelled “Longulac,” a locality not listed in

any Canadian gazetteer, was an enigma. We first assumed that “Longulac” was

actually Long Lake in Frontenac County east of Peterborough, which is where

Lindblom (1997) mapped it. However, the labels of a number of bryophyte specimens

at CANM collected between 15–20 July 1917 by Jennings from this locality all

were titled “Flora of Western Ontario.” The label for Plagiomnium medium (Bruch &

Schimp. in B.S.G.) T. Kop. elaborated on the locality “Longulac,” saying that it was

“1 mile south of Revillon.” Unfortunately (and frustratingly), that locality is also

absent from all Canadian gazetteers we consulted. There is, however, a “Longlac” in

the Thunder Bay District at the northern end of Long Lake, deep in the boreal forest,

Figure 2. Distribution of Xanthoria parietina in southern Ontario. = recent discoveries; =

historic collection. Shaded area is the Silurian dolomite belt (Ontario Ministry of Northern

Development and Mines 2003).

2007 Notes 303

and the bryophytes collected from Longulac are indeed boreal species (e.g., Bryum

pseudotriquetrum (Hedw.) Gärtn.; Meyer & Scherb., Plagiomnium ellipticum (Brid.)

T. Kop.; P. medium; and Aulocomium palustre (Hedw.) Schwaegr.) that are not

normally found in southern Ontario (Linda Ley, Canadian Museum of Nature,

Ottawa, ON, Canada, pers. comm.). Since Long Lake is also mentioned on the label,

this is almost surely the locality of the Xanthoria specimen, which would put a record

of Xanthoria parietina deep into the boreal forest, far out of its normal range. We

therefore borrowed the specimen from the US National Museum (US) and quickly

determined that it was actually Xanthomendoza hasseana , a very common boreal

species. In fact, Lindblom had identified the specimen correctly but somehow, the

record was mistakenly included with Xanthoria parietina for mapping.

The Agassiz no. 243 collection cited by Hinds (1995) was borrowed from the

Farlow Herbarium and could be confirmed as true X. parietina. The only locality

given on the label, “Lac Supérieur,” is too vague to enable us to determine

whether it was collected in Ontario or in one of the lake states in the United

States. We therefore were unable to map it. Other than that locality, all the

presently known localities of X. parietina in Ontario are indicated in Figure 2,

with the historic Belleville collection marked with a square.

Discussion. The intriguing question is whether Xanthoria parietina has, in

fact, returned to the region or whether it has been there all the time but, for some

reason, was never was noticed, or, at least, recorded, for 140 years. Is the southern

Ontario population physiologically and genetically different from the eastern

coastal populations? Possible explanations for the reappearance or expansion of

X. parietina in southern Ontario include 1) climatic conditions or even climate

change, 2) nutrient enrichment, 3) a salinity effect, and 4) accidental introduction.

There are few climatic similarities between the east coast and southern Ontario.

The climate is “oceanic mid-boreal” to “oceanic low boreal” on the coast (always

humid, with cool to warm summers, frequent fogs and mild winters) and relatively

continental inland: “humid high cool temperate” to “humid high moderate temperate”

(sometimes humid, but with hot summers, infrequent fog, and cold to mild winters)

(Ecoregions Working Group 1989). All the Ontario specimens have been found

growing on bark, never concrete, mortar, or any other “rock” substrate. By contrast,

along the east coast, Xanthoria parietina is often collected on concrete walls or fences

and even on rocky outcrops near the sea. In general, when lichens that are normally

corticolous are found on rock, the conditions surrounding the saxicolous sites are

especially moist, as would occur with frequent coastal fog. On the other hand, the

climate on the Lake Superior shore is quite oceanic and other coastal lichen species

occasionally are found there. For example, Xylographa opegraphella Nyl. ex Rothr.

has recently been reported from coastal localities in Michigan and Wisconsin (Bennett

2006) It is therefore conceivable that the Agassiz collection from the Lake Superior

region is from a humid lakeshore locality having an oceanic climate.

Xanthoria parietina is well known to respond positively to nutrient enrichment,

especially with nitrogen (Brodo 1968, Welch et al. 2006, and references therein).

Lindblom (1997) mentions the affinity of X. parietina for anthropogenous substrates.

Rapid industrial and agricultural development in southern Ontario in the 20th century

has contributed to significant increases in nitrogen deposition. Although leveling off

since 1980, NO3 deposition exceeds 25 kg/ha/yr in areas of southern Ontario (Environment

Canada 2004). McCune (2003) suggests that ammonia pollution (from cattle

urine and manure-saturated soils, and degassing from rivers) in the area around the

lower Wilson River in Oregon, has “created” suitable habitat for this nitrophilous

species (along with a few others), and has permitted it to invade the area where it

never occurred before. The same thing may have occurred in highly agricultural

southern Ontario over the past 60 or 70 years. Ammonia emissions are currently

304 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 14, No. 2

greater than 500 kg/km2 and are projected to increase over the next decade (Environment

Canada 2004). The abundance of Xanthoria parietina on trees near a drainage

ditch filled with run-off from surrounding fertilized fields lends support to the

possibility of an enrichment effect. The alignment of localities within the calcareous

Silurian dolomite corridor (Fig. 2) suggests that lime-rich dust in the region may also

be involved in the abundance of the species.

Hinds (1995) found that the distribution of Xanthoria parietina on gravestones in

Maine closely parallels the distribution of salt aerosols presumably emanating from the

nearby ocean shore, and he concluded that salt deposition was the deciding factor in

determining the occurrence of the species in that state. The increased use of road salt in

southern Ontario over the last 50–70 years could therefore be another reason for the

expansion of X. parietina in the region since the sites of most of the recent collections

are within close proximity to roadways where the use of salt is evident.

Lichens are occasionally introduced into an area by accident when their substrate,

such as young trees or boulders still supporting viable lichens, are brought into

an area. If this happened in southern Ontario, when might it have occurred?

It may be possible to estimate the time of arrival of these thalli and the direction of

their spread by measuring maximum thallus diameters in the various localities. European

studies cited in Hale (1973) give radial growth rates of up to 2.5 mm per year for

Xanthoria parietina, although measurements of the growth rate of individual thallus

lobes (0.3 mm/month) in Bristol, UK, suggest that a rate of 3.5 mm/year is possible (Hill

2002). Armstrong (1984) and Welch et al. (2006), however, found that moderate levels

of nitrogen enrichment can increase the growth rate of Xanthoria parietina. Based on

the sizes of the Ontario thalli, and assuming an approximate growth rate of 3.0 mm/year,

we can estimate the age of some of the populations.

The largest specimen found in Paisley, the northernmost locality (Fig. 2), was

less than 100 mm in diameter, whereas thalli in Hanover were up to 120 mm. These

thalli were growing on trees that were part of the original sub-division landscaping

done approximately 30 years ago. Of course, these trees would have been nursery

stock (5–10 years old) and not seedlings when they were planted. Assuming thallus

establishment took place after planting (not necessarily the case; see above), combined

with a consideration of thallus size and planting date, the thalli in Hanover are

likely anywhere from 17–20+ years old.

The specimens encountered in Arthur, south of both Hanover and Paisley, were

largest and covered the most area (especially on trees near the drainage ditch), and they

were growing on larger trees. Unfortunately, we could not measure the lichen diameters

since the thalli were growing relatively high up on a multi-stemmed Acer saccharinum

L. (silver maple). The trunks were still relatively smooth, just like Acer

platanoides L. (Norway maple) and Tilia sp. (little leaf linden) trunks and were

probably “suckers,” the result of a home owner cutting the original tree down, leaving a

stump. Cores of this tree could give more exact ages of thalli, but these Arthur

specimens are probably older than the ones found to the north (Hanover, Paisley,

Mount Forest, etc.). The largest thalli in the Hanover/Burlington area were approximately

300–320 mm in diameter. (No systematic observations of thallus diameter were

made in Guelph.) It is tempting to postulate that Xanthoria parietina populations are

therefore spreading from an area centered around Arthur both northward and southward,

but more controlled observations are needed, and this conclusion is very

tentative. Whether their origin in the region is by natural expansion or by introduction

on planted trees such as the nursery stock used in landscaping (see Lindblom 1997)

cannot easily be determined, except perhaps by genetic profiling.

Conclusions. It is now apparent that X. parietina is still very much a part of the

southern Ontario lichen flora and should be considered as potentially present in any

southern Ontario pollution monitoring surveys.

2007 Notes 305

Lichens have a well-deserved reputation for indicating environmental change.

Van Herk (2002) summarized methods for using lichens on roadside trees to assess

eutrophication (especially by ammonia pollution) in the Netherlands. These techniques

could be applied in future studies of the X. parietina populations in Ontario,

considering McCune’s (2003) suggestion that such environmental changes have

created suitable habitat for colonization (by new invasion or range expansion) in

Oregon. Xanthoria parietina seems to have a competitive advantage over other

foliose lichens, especially more acidophilic species, where levels of nitrogen enrichment

are particularly high (Welch et al. 2006). Recent eutrophication may thus

explain why the experienced collectors who visited southern Ontario in the first half

of the 20th century did not find X. parietina.

Although our purpose in this paper was to document the expansion of a rare

Ontario lichen, we must also point out that, if eutrophication is the cause of a range

expansion with respect to a nitrophilous lichen such as Xanthoria parietina, this

same eutrophication can result in the overall loss of lichen species diversity in the

region (Wolseley et al. 2006). Whereas nitrogen enrichment may increase the growth

of many lichens at low levels when nitrogen is a limiting factor, higher level of

nitrates and ammonium in the atmosphere are toxic to lichens, even X. parietina

(Welch et al. 2006).

Xanthoria parietina should be sought in inland localities throughout the region

and, indeed, throughout the northeast, so that we can better understand its distribution,

especially if it is changing.

Acknowledgments. We warmly thank Joan Crowe and Bruce Allen for the historic

information pertaining to Otto and Grace Jennings and their collections in

northwestern Ontario. We also thank Gregory McKee at the Smithsonian Institution

for locating and sending us the specimen from Longulac, and we thank Dr. Chris

Eckert at the Fowler Herbarium, Queens University, for checking the herbarium for

Xanthoria parietina records from Ontario. The manuscript benefited from the comments

and suggestions of Pak Yau Wong, Fenja Brodo, James Hinds, and David

Richardson. The distribution map was kindly produced by Noel Alfonso of the

Canadian Museum of Nature using ArcView GIS software. We are grateful to Donna

Naughton and Michelle LeBlanc, also of the Museum, who helped polish the figures.

Literature Cited

Armstrong, R.A. 1984. The influence of bird droppings and uric acid on the radial growth of

five species of saxicolous lichens. Environmental and Experimental Botany 24:95–99.

Bennett, J. 2006. New or overlooked Wisconsin lichen records. Evansia 23:28–33.

Brodo, I.M. 1968. The lichens of Long Island, New York: A vegetational and floristic

analysis. New York State Museum and Science service Bulletin 410:1–330.

Brodo, I.M., S.D. Sharnoff, and S. Sharnoff. 2001. Lichens of North America. Yale University

Press, New Haven, CT and London, UK. 795 pp.

Ecoregions Working Group. 1989. Ecoclimatic regions of Canada: First approximation.

Ecoregions Working Group of the Canada Committee on Ecological Land Classification

Series, No. 23, Sustainable Development Branch, Canadian Wildlife Service, Conservation

and Protection, Environment Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada. 119 pp.

Environment Canada. 2004. Canadian acid deposition science assessment 2004. Available online

at http://www.msc-smc.ec.gc.ca/saib/acid/acid_e.html. Accessed on February 16, 2006.

Hale, M.E. 1973. Growth. Pp. 473–492, In V. Ahmadjian and M.E. Hale (Eds.). The Lichens.

Academic Press, New York, NY and London, UK. 697 pp.

Hill, D.J. 2002. Measurement of lichen growth. Pp. 255–278, In I. Kranner, R. Beckett, and A.

Varma (Eds.). Protocols in Lichenology, Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany. 580 pp.

Hinds, J.W. 1995. Marine influence on the distribution of Xanthoria parietina, X. elegans, and

X. ulophyllodes on marble gravestones in Maine. Bryologist 98:402–410.

Hinds, J.W., and P.L. Hinds. 1993. The lichen genus Xanthoria in Maine. Maine Naturalist 1:1–16.

306 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 14, No. 2

Lindblom, L. 1997. The genus Xanthoria (Fr.) Th. Fr. in North America. Journal of the Hattori

Botanical Laboratory 83:75–172.

McCune, B. 2003. An unusual ammonia-affected lichen community on the Oregon coast.

Evansia 20:132–137.

Ontario Ministry of Northern Development and Mines. 2003. Geology and Selected Mineral

Deposits of Ontario [map]. Available online at http://www.mndm.gov.on.ca/mndm/mines/

ogs/geology_map_e.asp. Accessed October 23, 2006.

Rudolph, E.D. 1955. Revisionary studies in the lichen family Blasteniaceae in North America

north of Mexico. Ph.D. Dissertation. Washington University, St. Louis, MO.

Sharnoff, S.D., and S. Sharnoff. 1997. Lichens: More than meets the eye. National Geographic

191(2):58–71.

Van Herk, C.M. 2002. Epiphytes on wayside trees as an indicator of eutrophication in the

Netherlands. Pp. 285–289, In P.L. Nimis, C. Scheidegger, and P.A. Wolseley (Eds.).

Monitoring with Lichens—Monitoring Lichens. NATO Science Series, Series IV: Earth

and Environmental Sciences, vol. 7. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands,

Boston, MA, and London, UK. 408 pp.

Welch, A.R., M.P. Gillman, and E.A. John. 2006. Effect of nutrient application on growth rate

and competitive ability of three foliose lichen species. Lichenologist 38:177–186.

Wolseley, P.A., P.W. James, M.R. Theobald, and M.A. Sutton. 2006. Detecting changes in

epiphytic lichen communities at sites affected by atmospheric ammonia from agricultural

sources. Lichenologist 38:161–176.

Wong, P.Y., and I.M. Brodo. 1992. The lichens of southern Ontario. Syllogeus 69:1–79.

Appendix 1. Specimens seen. Specimens collected by authors B. Craig and C. Lewis were sent

to I.M. Brodo for verification. A variety of habitats along a total of 92 km of road were

surveyed, and 60–70 trees were examined. The specimens were studied using standard stereomicroscopic

techniques, and vouchers were deposited in the National Herbarium of Canada

(CANL) at the Canadian Museum of Nature.

Xanthoria parietina

Canada. Ontario. BRUCE COUNTY: Paisley, (approx. 25 km NW of Hanover), 44°18'N,

81°16'W, C. Lewis 2, 28 Dec. 2005 (CANL); DUFFERIN COUNTY: Orangeville, 43°54'N,

80°9'W, Lewis 120, 28 Jan. 2006 (CANL); County Road 109 between Orangeville and Arthur,

43°51'N, 80°24'W, C. Lewis 121, 28 Jan. 2006 (CANL); Shelburne, 44°04'N, 80°11'W, C.

Lewis 125, 29 Jan. 2006 (CANL); DURHAM COUNTY: Bowmanville (Municipality of

Clarington), Along Soper Creek, East Branch, 43°53'N, 78°40'W, on Acer negundo, C. Lewis,

s.n., 26 July 2006 (CANL); GREY COUNTY: Hanover, 44°9'N, 81°2'W, C. Lewis 1, 18 June

2005 (CANL); HALDIMAND COUNTY: North of Dunnville, on Fraxinus americana,

42°59'30.9"N, 79°40'53.8"W, B. Craig, s.n., August 2002 (CANL); HALTON COUNTY:

Burlington, just outside the Canada Centre for Inland Waters, adjacent to Lake Ontario,

growing on Tilia sp., 43°17'58.6"N, 79°47'58.2"W, B. Craig, 14 March 2004 (CANL);

HASTINGS COUNTY: Belleville, Macoun 533 (42), 1868 (CANL); VICTORIA COUNTY:

Reaboro, 44º19'N, 78º39'W, C.Lewis (photo voucher). WELLINGTON COUNTY: Arthur (405

George St.), 43°50'N, 80°32'W, C. Lewis 122, 123, 28 Jan. 2006 (CANL); Mount Forest,

44°0'N, 80°46'W, C. Lewis 124, 28 Jan. 2006 (CANL); Guelph, University of Guelph Arboretum,

on Salix sp., 43°32' 08.9"N, 80°12' 57.2"W, B. Craig, s.n., 12 July 2002 (CANL).

Locality uncertain: “Lac Supérieur,” L. Agassiz 243, 1868 (FH).

Xanthomendoza hasseana

Canada. Ontario. THUNDER BAY DISTRICT: “On dead Populus balsamifera. H.B. [Hudson

Bay] Post, Longulac [Longlac], Long Lake, Ontario,O.E. and G.K. Jennings, 12 July 1917”

(US). Det. by C.C. Plitt as Xanthoria parietina; annotated by L. Lindblom as X. hasseana.

1Canadian Museum of Nature, PO Box 3443, Station “D,” Ottawa, ON K1P 6P4 Canada.

2Biology Department, Trent University, 1600 West Bank Drive, Peterborough, ON K9J 7B8

Canada. 3Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network Coordinating Office, Environment

Canada, Canada Centre for Inland Waters, 867 Lakeshore Road, Burlington, ON L7R 4A6

Canada. 4Current address - Southwestern Ontario Field Unit, Parks Canada Agency, 15 Duke

Street East, Kitchener, ON N2H 1A2 Canada. *Corresponding author - ibrodo@mus-nature.ca.

The Northeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within northeastern North America. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.

The Northeastern Naturalist is a peer-reviewed journal that covers all aspects of natural history within northeastern North America. We welcome research articles, summary review papers, and observational notes.