2010 NORTHEASTERN NATURALIST 17(1):49–62

Plant Communities of the Burden Hill Forest,

Salem County, New Jersey

Stevens Heckscher1,*, James F. Thorne1, Mike Bertram1, and Michael Ward1

Abstract - The plant community types on three tracts within the Burden Hill Forest,

a distinctive outlier of the New Jersey Pine Barrens, are described and classified.

While these tracts consist largely of a general pine barrens type, they display a

number of significant differences from the main body of the Pine Barrens. These

differences include additional forest plant community types previously undescribed

for New Jersey, higher heterogeneity of community types and woody plant diversity,

and the presence of several unusual or rare species including Castanea pumila (Allegheny

Chinquapin).

Introduction

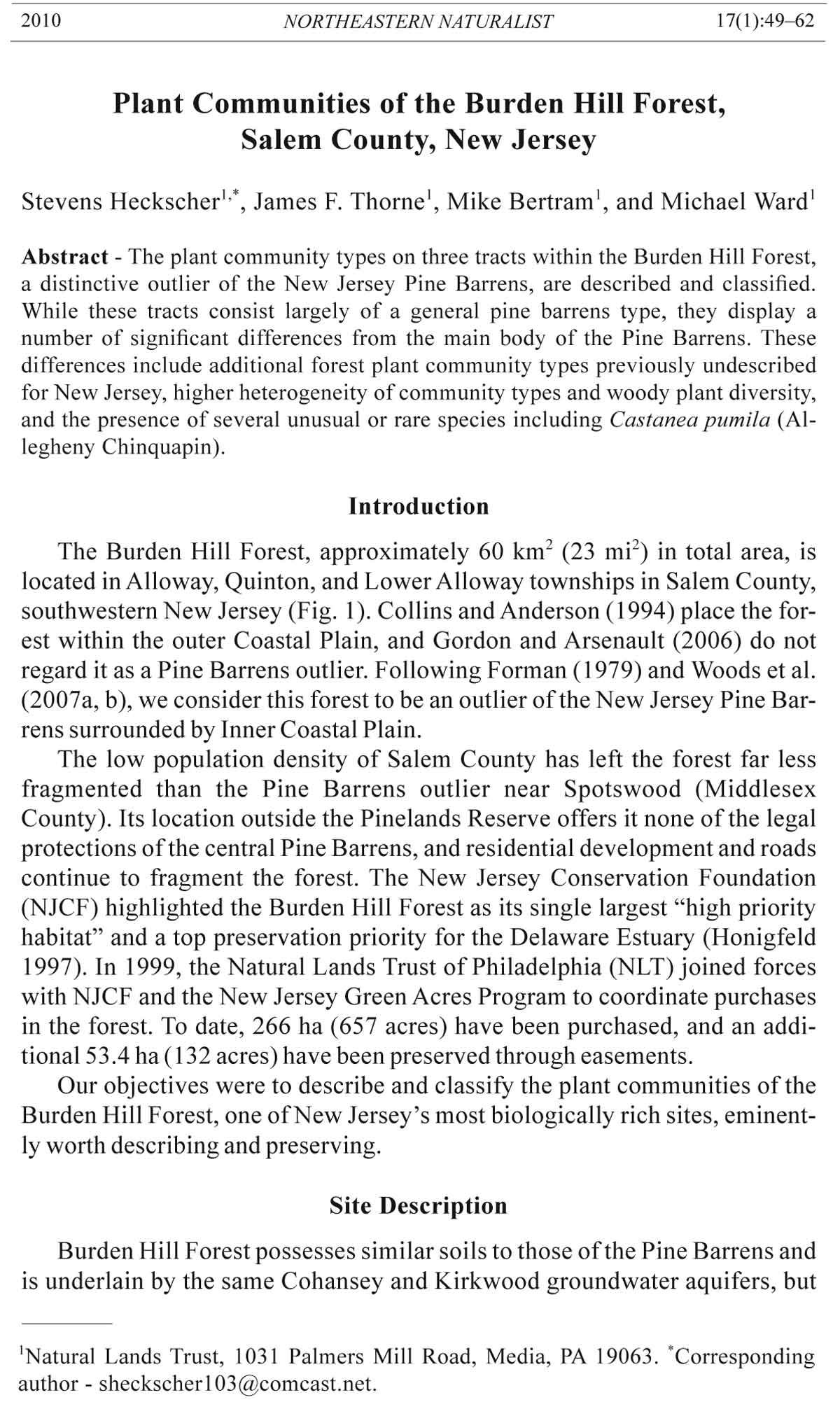

The Burden Hill Forest, approximately 60 km2 (23 mi2) in total area, is

located in Alloway, Quinton, and Lower Alloway townships in Salem County,

southwestern New Jersey (Fig. 1). Collins and Anderson (1994) place the forest

within the outer Coastal Plain, and Gordon and Arsenault (2006) do not

regard it as a Pine Barrens outlier. Following Forman (1979) and Woods et al.

(2007a, b), we consider this forest to be an outlier of the New Jersey Pine Barrens

surrounded by Inner Coastal Plain.

The low population density of Salem County has left the forest far less

fragmented than the Pine Barrens outlier near Spotswood (Middlesex

County). Its location outside the Pinelands Reserve offers it none of the legal

protections of the central Pine Barrens, and residential development and roads

continue to fragment the forest. The New Jersey Conservation Foundation

(NJCF) highlighted the Burden Hill Forest as its single largest “high priority

habitat” and a top preservation priority for the Delaware Estuary (Honigfeld

1997). In 1999, the Natural Lands Trust of Philadelphia (NLT) joined forces

with NJCF and the New Jersey Green Acres Program to coordinate purchases

in the forest. To date, 266 ha (657 acres) have been purchased, and an additional

53.4 ha (132 acres) have been preserved through easements.

Our objectives were to describe and classify the plant communities of the

Burden Hill Forest, one of New Jersey’s most biologically rich sites, eminently

worth describing and preserving.

Site Description

Burden Hill Forest possesses similar soils to those of the Pine Barrens and

is underlain by the same Cohansey and Kirkwood groundwater aquifers, but

1Natural Lands Trust, 1031 Palmers Mill Road, Media, PA 19063. *Corresponding

author - sheckscher103@comcast.net.

50 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 17, No. 1

is separated from the central pinelands by twenty miles of more fertile coastal

plain soils. According to the Salem County Soil Survey (USDA 1969), the

dominant soil association for Burden Hill is the Sassafras-Evesboro-Downer

Association, which supports mostly very droughty and nutrient-poor soils.

The Soil Survey notes that areas abandoned from agriculture tend to grow

up in pines.

Burden Hill is the largest forest in Salem County. Robichaud and Buell

(1973) describe this forest as mostly a type of mixed oak forest, similar to

the oak-pine forests of the Pine Barrens. Its wetlands consist of seeps, small

streams, vernal ponds, and a permanent dammed pond. These contain extensive

stands of Helonias bullata L. (Swamp Pink), a federally listed plant, as

well as the state-protected Listera australis Lindl. (Southern Twayblade).

Castanea pumila (L.) P. Mill. (Allegheny Chinquapin), a state-endangered

species, is scattered throughout the forested upland areas (S. Heckscher,

pers. observ.). The forest is home to two state-listed birds known for their

affinities to large tracts of mature, unbroken forest: Buteo lineatus Gmelin

(Red-shouldered Hawk) and Strix varia Barton (Barred Owl).

F i g u r e 1 .

Location of

study area in

Burden Hill

Forest.

2010 S. Heckscher, J.F. Thorne, M. Bertram, and M. Ward 51

We studied three tracts of the Burden Hill Forest recently acquired and

now managed by the NLT: the Alloway Tract (62.9 ha [155.4 acres]), the

Cool Run Tract (84.8 ha [209.5 acres]), and the Route 49 Tract (34.7 ha [85.7

acres]) (Fig. 1). Using the results of this study, NLT has produced a management

plan for its holdings in this forest (Natural Lands Trust 2004).

Methods

Botanical nomenclature follows Kartesz (1994). Woody plants with a

diameter at breast height (DBH) greater than or equal to 10 cm were classified

as trees, and woody plants with a DBH ranging from 1 cm to 10 cm

were classified as shrubs. Shrub stems were counted individually when

they were separate and distinguishable at ground level.

Sampling design

Our method for sampling the vegetation was a stratified, iterative design

similar to that used by Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry (2001). A color infrared

aerial photograph of the entire Burden Hill forest was overlaid onto

a GIS base map of the three study tracts (ESRI n.d., version 9.1). Polygons

were drawn on the GIS map of each tract, each bounding an area more or

less uniform in color and texture and considered to represent a distinct forest

community type. On this map, we superimposed a square, north–south,

east–west grid system, creating 0.4-ha quadrats. We randomly selected

sampling quadrats until the sampling area totaled a minimum of 10% of the

total area of each polygon. A few polygons were too small or too narrow to

fully contain quadrats, and were not included in the analyses. These were

examined in the field, and their community classifications were determined

by direct inspection.

Data collection in the field

We placed two concentric, circular sampling plots (20-m and 5-m diameters)

at the center of each randomly selected quadrat. We counted and

recorded the DBH of each tree within the larger plots and tallied the number

of shrub stems within the smaller plots. For each tree species in each plot, we

calculated relative density (number of stems for the species / total number of

tree stems), relative dominance (total basal area for the species / total basal

area for all tree species), and importance value (100 * [relative density +

relative dominance] / 2). For each shrub species in each plot, we calculated

relative density (number of stems for the species / total number of shrub

stems) and importance value (100 * relative density).

Analyses

We used multivariate analyses on four data sets for the purposes of delineation

and naming of community types: (1) on tree data from each of

the three tracts, with each tract examined separately; (2) on tree data from

all three tracts combined into a single data set; (3) on shrub data from each

of the three tracts separately; and (4) on shrub data from all three tracts

52 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 17, No. 1

combined into a single data set. We used TWINSPAN to detect patterns in

the data and to help us to name and describe community types. To search for

additional patterns in the data, we also ran on each of the data sets (2) and

(4) a detrended correspondence analysis (DECORANA), principal components

analysis, and two cluster analyses using Euclidean distances, the first

with separation by distances between centroids, and the second by distances

between nearest neighbors. The software used for these programs was PCORD

(McCune and Mefford 1997).

Using the results of the TWINSPAN runs, community types consisting

of categories subdivided into community elements were named, described

according to dominant and other important species present, and mapped. We

used the polygons mapped earlier as guidelines wherever possible. Several

additional forays were then made into the field, ensuring that each community

type on each tract was carefully inspected at least once, and amendments

to the maps were made accordingly.

Where possible, community elements and categories that we identified

were then cross-referenced (crosswalked) to plant community classifications

in the second iteration of the New Jersey Vegetation Classification

(NJVC) (Breden et al. 2001). We made note of significant differences between

our results and those of NJVC, and these are noted in the discussion

section below.

Results

We assessed and mapped the plant community types for the Alloway

Tract (Fig. 2), the Cool Run Tract (Fig. 3), and the Route 49 Tract (Fig. 4)

in the Burden Hill Forest. Detailed descriptions of each of these community

types follows.

Acidic soils

Pitch Pine forest. On the Burden Hill tract, this category consists only of

a small stand of Pinus rigida P. Mill. (Pitch Pine) of questionable etiology—

probably planted years ago, or a successional pine community. It is poorly

represented here, and for these reasons it is not divided into community elements.

Moreover, on the Route 49 Site there is a recently disturbed area now

being colonized by a stand of Pinus rigida seedlings and saplings, marked

“early Pitch Pine regeneration” (EP) on Figure 4.

Broadleaf or broadleaf-needleleaf forest with a heath-shrub understory.

Community elements in this category are those with a broadleaf, or

broadleaf and needleleaf, more or less closed, canopy over a heath-shrub

understory. Oaks, especially Quercus alba L. (White Oak), predominate

among the broadleaf species, and Pinus rigida is the most important

needleleaf tree. The colonial species Gaylussacia baccata (Wangenh.) K.

Koch (Black Huckleberry) is generally dominant in the shrub layer, and

provides a fairly good indicator species for this category. Community elements

are as follows:

2010 S. Heckscher, J.F. Thorne, M. Bertram, and M. Ward 53

Xeric-mesic oak: This xeric-mesic hardwood community is dominated by

Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees (Sassafras) and the following oaks in various

combinations: Quercus alba, Q. coccinea Muenchh. (Scarlet Oak), Q. falcata

Michx. (Southern Red Oak), and Q. velutina Lam. (Black Oak). Castanea

pumila is sometimes present, and Carya glabra (P. Mill.) Sweet (Pignut

Hickory) is scattered throughout. Pinus rigida is absent, although P. virginiana

P. Mill. (Scrub Pine) may be present as an oldfield relic. The shrub layer

appears to be extremely depauperate, with the only species recorded in it

during our data collection being Gaylussacia baccata.

Oak-pine: In this xeric-mesic community element, the following oaks in

varying combinations co-dominate: Quercus alba, Q. falcata, Q. coccinea,

Q. velutina, and Q. prinus L. (Chestnut Oak). Pinus rigida is always present,

sometimes as a co-dominant, and was regarded by us as an indicator species

separating this community element from the xeric-mesic oak community

element. Sassafras albidum is present and often abundant. Other hardwoods

sometimes present include Acer rubrum L. (Red Maple), Ilex opaca Ait.

(American Holly), Liquidambar styraciflua L. (Sweet Gum), Nyssa sylvatica

Marsh. (Black Gum), and Prunus serotina Ehrh. (Black Cherry). Castanea

Figure 2. Alloway

Site: woody plant

communities as

determined by

this study. Small

circles denote

sampling points.

Note that community

types are

often not sharply

delineated;

boundaries between

them are

usually more or

less gradual. AC

= Atlantic White

Cedar Swamp,

DPP = disturbed

Pitch Pine and

Black Cherry,

EP = early Pitch

Pine regeneration,

MH = mixed hardwoods, MHH = mesic-hydric hardwoods with lowland pitch

pine, MHL = mature mixed hardwoods with Mountain Laurel shrub layer, MV =

mid-successional oldfield with Virginia Pine, OF = open field, OH = oak-American

Holly, OL = oak-Mountain Laurel, OP = oak-pine, OS = open shrubland with Water

Willow, PP = Pitch Pine forest, PRB = Red Maple-Black Gum palustrine forest, PRP

= permanent pond, RMR = Red Maple-Black Gum-Sweetbay Magnolia riparian forest,

SP = seasonal pond, and XM = xeric-mesic oak.

54 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 17, No. 1

pumila is present and varies from sparse to abundant. Stump sprouts of

C. dentata (Marsh.) Borkh. (American Chestnut) were found in two quadrats.

Pinus echinata P. Mill. (Shortleaf Pine) is present but sparse, while

Pinus virginiana and Juniperus virginiana L. (Red Cedar) are often present,

probably as oldfield relicts. A few hickories, i.e., Carya glabra and C. alba

(L.) Nutt. ex Ell. (SY = C. tomentosa (Lam. ex Poir.) Nutt.) (Mockernut

Hickory), are sometimes present. In the shrub-layer, Smilax glauca Walt.

(Glaucous Greenbriar) and S. rotundifolia L. (Greenbriar) are sparse, along

with the usually abundant Gaylussacia baccata and Vaccinium pallidum Ait.

(Hillside Blueberry).

Oak-American Holly: Oaks—Quercus prinus, Q. falcata, and Q. coccinea—

dominate. Ilex opaca is likely the most abundant element of the

subcanopy, and Acer rubrum is present in small numbers. The shrub layer,

dominated by Gaylussacia baccata, is species-poor, but may contain Kalmia

latifolia L. (Mountain Laurel).

Oak-Mountain Laurel: Oaks—Quercus coccinea, Q. alba, Q. falcata,

and Q. prinus—co-dominate with Sassafras albidum. Pinus rigida and

Figure 3. Cool Run Site: woody plant communities as determined by this study. Small

circles denote sampling points. Note that community types are often not sharply

delineated; boundaries between them are usually more or less gradual. See Figure 2

for community abbreviations.

2010 S. Heckscher, J.F. Thorne, M. Bertram, and M. Ward 55

P. virginiana are present but variable, as is Castanea pumila. The shrub layer

consists of Gaylussacia baccata with Kalmia latifolia, which may be very

dense in places where little grows under it, and Vaccinium pallidum.

Disturbed Pitch Pine and Black Cherry: In this disturbed element, Pinus

rigida and Prunus serotina are most abundant. Other hardwoods of some

importance include (in order of decreasing abundance) Cornus florida L.

(Flowering Dogwood), Sassafras albidum, and Castanea pumila. Oaks are

sparse. Juniperus virginiana, an oldfield relic, is present. In the shrub layer,

Kalmia latifolia and Gaylussacia baccata are present and may be abundant.

This community type occurs only in a small polygon of the Cool Run

tract that has been heavily disturbed, so this description must be regarded

as provisional.

Rich soils

Rich broadleaf forest (“mixed oak”). This category appears to be a

variant of the "mixed oak forest" of Collins and Anderson (1994). It is

Figure 4. Route 49 Site: Woody plant communities as determined by this study. Small

circles denote sampling points. Note that community types are often not sharply

delineated; boundaries between them are usually more or less gradual. See Figure 2

for community abbreviations.

56 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 17, No. 1

characterized by a mixture of oaks, with other hardwoods, and little or no

pine. Community elements are as follows:

Mature mixed hardwoods with a Mountain Laurel shrub layer: This

community element consists of the most mature hardwood stand encountered

in this study. Oaks include at least Quercus falcata, Q. coccinea, and

Q. alba. Stump sprouts of Castanea dentata are present. Other hardwoods

include Carya alba (SY = C. tomentosa), C. glabra, Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.

(American Beech), Cornus florida, Sassafras albidum, and Ilex opaca. The

understory is unevenly dominated by Kalmia latifolia. This type is quite

possibly a more mature version of the oak-Mountain Laurel element, as described

above.

Mixed hardwoods: This community element differs from the last in that

here Kalmia latifolia is absent. It contains a mixture of oaks including Quercus

falcata, Q. coccinea, and Q. alba. Other hardwoods may include any of

the following: Carya alba (SY = C. tomentosa), C. glabra, Fagus grandifolia,

Cornus florida, Sassafras albidum, and Ilex opaca. Scattered pines and

Castanea dentata stump sprouts may occasionally be present.

Hydric soils

Red Maple-Black Gum riparian or palustrine forest. This category consists

of riparian or palustrine forests dominated by Acer rubrum, with Nyssa

sylvatica present but often sparse. Gaylussacia species, Vaccinium species,

Clethra alnifolia L. (Sweet Pepperbush), and Rhododendron viscosum (L.)

Torr. (Swamp Azalea) are often present in the shrub layer. Community elements

are as follows:

Red Maple-Black Gum-Sweetbay Magnolia riparian forest: Acer rubrum

is dominant. Nyssa sylvatica and Magnolia virginiana L. (Sweetbay Magnolia)

are present but may be sparse. Clethra alnifolia, Gaylussacia frondosa

(L.) Torr. & Gray ex Torr. (Dangleberry), and Rhododendron viscosum are

found in the shrub layer. While not reported in our data for this element,

Vaccinium corymbosum L. (Highbush Blueberry) has been seen locally

and should be looked for here, where it is probably quite common. Also to

be looked for here are Ilex verticillata (L.) Gray (Winterberry), Leucothoe

racemosa (L.) Gray (Deciduous Swamp Fetterbush), and Ilex glabra (L.)

Gray (Inkberry).

Red Maple-Black Gum palustrine forest: Acer rubrum is dominant.

Nyssa sylvatica is present but may be sparse. The shrub layer contains

Gaylussacia baccata, Vaccinium pallidum, and V. corymbosum. The single,

small polygon containing this community element, on the Route 49

tract, has been strongly modified by recent disturbance, so this description

must be regarded as provisional.

Hydric broadleaf-needleleaf forest. Description for the only community

element, below.

Mesic-hydric hardwoods with lowland Pitch Pine: Of importance are Nyssa

sylvatica, Ilex opaca, and Pinus rigida. Small numbers of Acer rubrum

2010 S. Heckscher, J.F. Thorne, M. Bertram, and M. Ward 57

are present; this paucity, combined with the abundance of Pinus rigida, distinguish

this community element from the Red Maple-Black Gum-Sweetbay

Magnolia riparian forest element, where A. rubrum is dominant. Castanea

pumila is sometimes present. Facultative wetland hardwoods include

Liriodendron tulipifera L. (Tulip Tree), Quercus falcata, and Liquidambar

styraciflua. Wetland indicators Quercus bicolor Willd. (Swamp White Oak)

and Magnolia virginiana are present but in small numbers. Vaccinium

corymbosum, Gaylussacia baccata, G. frondosa, Clethra alnifolia, Leucothoe

racemosa, and Lyonia ligustrina (L.) DC (Maleberry) are often abundant

in the shrub layer. Rhododendron viscosum is not present in our data

for this community element, although according to NJVC it probably occurs

here.

Atlantic White Cedar swamp. This is not divided into community elements.

It consists of swamp forest strongly dominated by Chamaecyparis

thyoides (L.) B.S.P. (Atlantic White Cedar).

Miscellaneous

Mid-successional oldfield with Virginia Pine. This type is not divided

into community elements. It is dominated by Pinus virginiana, apparently

succeeding to hardwoods.

Open shrubland with Water Willow. This type is not divided into community

elements. It consists of hydric shrubland with a high density of Decodon

verticillatus (L.) Ell. (Water Willow).

Discussion

In this study, we have made a first attempt at naming, describing, and

mapping the woody plant communities on three tracts in the Burden Hill Forest,

classifying the communities into categories subdivided into community

elements. Because we are working at a far finer scale, our names deliberately

reflect a finer detail than those of Breden et al. (2001). Figures 2–4 show the

locations of our community types.

The Burden Hill Forest differs from the main New Jersey Pine Barrens

in at least two respects. First, the forest appears more heterogeneous, displaying

a rich mosaic of different plant community types. For example, the

oak-dominated communities have higher species diversity of oaks and other

woody plants, including the rare Castanea pumila, and a greater abundance

of Ilex opaca in places in the understory. Secondly, the C. pumila, while

quite common at Burden Hill, is scarcely found elsewhere in the state.

One similarity of the Burden Hill Forest to the main New Jersey Pine

Barrens is important. Our second category, broadleaf or broadleaf-needleleaf

forest with a heath-shrub understory, consists of mixed hardwoods, with or

without Pitch Pine, over heath shrubs, mainly the colonial and clonal Gaylussacia

baccata (Black Huckleberry). This composition suggests strongly

that this category belongs to the generalized, fire-adapted pine-oak heath

58 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 17, No. 1

type (Whittaker 1979) common not only in the New Jersey Pine Barrens, but

also on acidic ridgetops in the Piedmont and Ridge and Valley provinces, and

elsewhere. According to Little (1979), fire has been a significant ecological

factor in shaping community types in large parts of the Burden Hill area, as

is true with the main Pine Barrens, but there is some controversy over this

point, and the shrub or small tree Quercus ilicifolia Wangenh. (Bear Oak)

common in openings of this forest type in the main Pine Barrens, is nearly

or completely absent on our Burden Hill project area.

It is also instructive to compare our findings to those of Olsson (1979),

which covered the “central fifth of the New Jersey Pine Barrens.” Our

second category, broadleaf or broadleaf-needleleaf forest with a heath-shrub

understory, corresponds most closely to Olsson’s pine-oak vegetation type.

His Entity A1, Pinus rigida-Quercus ilicifolia, differs from our second

category in its abundance of Q. ilicifolia in the understory. His Entity A3,

Quercus alba-Q. prinus-Q. velutina, is similar to our second category except

that in our study area, Q. ilicifolia appears to be nearly or completely absent,

Q. falcata is present, and Q. prinus is comparatively less abundant.

Although Ilex opaca occurs at least sporadically in poorer-drained

sites throughout much of the New Jersey Pine Barrens, nothing similar to

our oak-American Holly community element appears in Olsson’s (1979)

classification or that of NJVC. While this type apparently does not occur

in the main body of the Pine Barrens, a similar community type does

occur in the Glades Region of New Jersey’s Cumberland County near

Fortescue (Heckscher 1994). This region lies near the Delaware Bayshore

about 25 miles to the southeast of the Burden Hill Forest. More or less

dense stands of Ilex opaca are probably widely distributed in Cumberland

and Cape May counties, and also on New Jersey’s Inner Coastal Plain

(anonymous reviewer, pers. comm.). See Collins and Anderson (1994)

for comments on American Holly in southern New Jersey. Likely factors

influencing the distribution of I. opaca and other species at Burden Hill

include proximity to the Inner Coastal Plain, where I. opaca is more common,

as well as soils, geology, and a more southerly climate than that of

the main Pine Barrens.

Gordon and Arsenault (2006) point out that, at Burden Hill, needleleaf

evergreen species such as Pinus rigida and P. echinata “occupy gaps or scars

of exposed mineral soil created by traditional land uses, and other smallscale

forest disturbances.” They attribute to the proximity of the rich Inner

Coastal Plain of south Jersey the presence at Burden Hill of at least seven

deciduous hardwood tree species.

As a contribution towards the ongoing work of classification of plant

communities in New Jersey, in Table 1 we have cross-referenced (crosswalked)

our groupings (categories and community elements) to NJVC; i.e.,

we have indicated the alliances and plant associations of NJVC into which

our groupings most nearly fit. Some of our groupings do not have clear crosswalks

to the present iteration of NJVC. We list and discuss these difficulties

2010 S. Heckscher, J.F. Thorne, M. Bertram, and M. Ward 59

Table 1. Cross- references (crosswalks) for the plant community elements found by us at the Burden Hill Forest, NJ, to the corresponding alliances and plant

associations reported in the New Jersey Vegetation Classification (NJVC) (Breden et al. 2001).1

Burden Hill element NJVC alliance NJVC plant association

Xeric-mesic oak I.B.2.N.a.100: Quercus velutina-Quercus alba- Quercus coccinea–Quercus velutina/

(Quercus coccinea) forest Sassafras albidum/Vaccinium pallidum

forest

Oak-pine I.C.3.N.a.35: Pinus (rigida, echinata)-Quercus Ambiguous; see text

coccinea forest; a poor fit; see text

Oak-American Holly Unknown

Oak-Mountain Laurel I.B.2.N.a.100: Quercus velutina-Quercus alba- Quercus velutina-Quercus coccinea-

(Quercus coccinea) forest Quercus montana (SY = Q. prinus)/

Kalmia latifolia forest

Disturbed Pitch Pine and Black Cherry Unknown

Mature mixed hardwoods with a Mountain Laurel shrub layer Belongs to formation I.B.2.N.a: lowland or Ambiguous; see text

submontane cold-deciduous forest; alliance

ambiguous, but see text

Mixed hardwoods Possibly I.B.2.N.a.31: Quercus falcata forest, Unknown

a poor fit; see text

Red Maple-Black Gum-Sweetbay Magnolia riparian forest I.B.2.N.g.2: Acer rubrum-Nyssa sylvatica Acer rubrum-Nyssa sylvatica/

saturated forest Rhododendron viscosum-Clethra

alnifolia forest

Red Maple-Black Gum palustrine forest I.B.2.N.g.2: Acer rubrum-Nyssa sylvatica Acer rubrum-Nyssa sylvatica-Magnolia

saturated forest virginiana forest

Mesic-hydric hardwoods with lowland Pitch Pine I.C.3.N.d.300: Pinus rigida-Acer rubrum Pinus rigida-Acer rubrum/Rhododendron

saturated forest viscosum forest

Atlantic White Cedar swamp I.A.8.N.g.2: Chamaecyparis thyoides Chamaecyparis thyoides/Ilex glabra forest

saturated forest

Mid-successional oldfield with Virginia Pine Possibly I.C.3.N.a.27: Pinus virginiana-Quercus Unknown

(alba, stellata, falcata, velutina) forest; see text

Open shrubland with Water Willow Unknown

1Because it is small, fragmentary, and probably a remnant of a planted area, our element Pitch Pine forest is not shown in this table (see text).

60 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 17, No. 1

next, and we suggest that they may reveal gaps in the present iteration of

NJVC, where further study is needed.

Oak-pine: This community element fits uneasily into NJVC’s alliance

I.C.3.N.a.35, PINUS (RIGIDA, ECHINATA)-QUERCUS COCCINEA FOREST,

corresponding poorly to the descriptions of both its NJVC associations,

as follows:

Pinus (rigida, echinata)-Quercus coccinea/Ilex opaca forest (our oak-pine

element is probably on drier soil).

Pinus rigida-Quercus coccinea/Vaccinium pallidum-(Morella [=Myrica]

pensylvanica Loisel.) forest.

Oak-American Holly: Because pines are absent from our data on this

community element on Burden Hill, and also apparently from its polygon

as seen on the infrared aerial photograph, we cannot crosswalk this element

to NJVC’s PINUS (RIGIDA, ECHINATA)-QUERCUS COCCINEA / ILEX

OPACA FOREST (under I.C.3.N.a.35). Indeed, we cannot find any alliance

or association in NJVC to which this community element can be crosswalked.

Further study is needed, but see the references to American Holly in

Collins and Anderson (1994), and our discussion above.

Disturbed Pitch Pine and Black Cherry: We can find no fit in NJVC for

this community type, which appears to be the result of recent disturbance.

Mature mixed hardwoods with a Mountain Laurel shrub layer: While

this element clearly belongs to formation I.B.2.N.a, lowland or submontane

cold-deciduous forest, its understorey dominance by Kalmia latifolia renders

assignment to a current NJVC alliance difficult or impossible. This type may

be a more mature successional stage of oak-Mountain Laurel (q.v.), in which

case it could fit into alliance I.B.2.N.a.100, QUERCUS VELUTINA-QUERCUS

ALBA-(QUERCUS COCCINEA) FOREST and association Quercus velutina-

Quercus coccinea-Quercus montana forest. We suggest further study.

Mixed hardwoods: The NJVC alliance that most nearly corresponds to

this Burden Hill element is I.B.2.N.a.31, QUERCUS FALCATA FOREST,

but the fit is poor and no appropriate association can be found in the current

iteration of NJVC; indeed, the latter document indicates the need for further

study to assess the distribution of this alliance.

Mid-successional oldfield with Virginia Pine: The alliance I.C.3.N.a.27, to

which this community type may crosswalk, apparently does not contain midsuccessional

communities. To the best of our knowledge, no mid-successional

oldfield communities dominated by Pinus virginiana are presently covered in

NJVC, but such communities are discussed in Collins and Anderson (1994).

Open shrubland with Water Willow: We could find no alliance in NJVC into

which this Burden Hill community element can fit. We suggest further study on

this element at Burden Hill where it occupies only a small area, and elsewhere.

2010 S. Heckscher, J.F. Thorne, M. Bertram, and M. Ward 61

This paper is a preliminary study of portions of the Burden Hill Forest.

As such, we believe, it adds new content to our knowledge and understanding

of plant community types in New Jersey. We hope that our work will

contribute towards the next iteration of NJVC, and that, as additional portions

of this valuable tract are protected, further ecological studies covering

more of the forest will be carried out.

Acknowledgments

During the course of this study, we have received suggestions and other forms of

assistance from a number of individuals, to whom we gratefully extend our thanks.

These include Ann Rhoads, Roger Latham, Steve Eisenhauer, Joe Arsenault, Ted

Gordon, Kay Baker, Andy Selleman, Glen Mittelhauser, and three anonymous reviewers.

Rebecca McGuire and Mike McGeehin meticulously prepared the maps on

a GIS system. This research was supported in part by generous grants to the Natural

Lands Trust by the Beneficia Foundation, the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, and

the William Penn Foundation.

Literature Cited

Breden, T.F., Y.R. Alger, K.S. Walz, and A.G. Windisch. 2001. Classification of

vegetation communities of New Jersey: Second iteration. Association for Biodiversity

Information and New Jersey Natural Heritage Program, Office of Natural

Lands Management, Division of Parks and Forestry, New Jersey Department of

Environmental Protection, Trenton, NJ. xiii + 240 pp.

Collins, B.R., and K.H. Anderson. 1994. Plant Communities of New Jersey: A Study

in Landscape Diversity. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ. 287 pp.

Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI, Inc.). No Date. Geographic

Information Systems (GIS) Software, version 9.1.

Forman, R.T.T. (Ed.). 1979. Pine Barrens: Ecosystem and Landscape. Academic

Press, New York, NY.

Gordon, T., and J. Arsenault. 2006. A flora of the Burden Hill Forest: A floristic

survey of selected properties of the Natural Lands Trust in Alloway and Quinton

Townships, Salem County, New Jersey. Prepared for the Natural Lands Trust,

Media, PA. 16 + 2 + xx + 20 pp.

Heckscher, S. 1994. The vegetation of the Glades Region, Cumberland County, New

Jersey. Bartonia 58:101–113.

Honigfeld, H.B. 1997. Charting a Course for the Delaware Bay Watershed. New

Jersey Conservation Foundation, Far Hills, NJ. viii + 156 pp.

Kartesz, J.T. 1994. A Synonymized Checklist of the Vascular Flora of the United

States, Canada, and Greenland. Volume 1—Checklist. Second Edition. Timber

Press, Portland, OR. lxi + 622 pp.

Little, S. 1979. Fire and Plant Succession in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. Pp. 297–

314, In R.T.T. Forman (Ed.). Pine Barrens: Ecosystem and Landscape. Academic

Press, New York, NY.

McCune, B., and M.J. Mefford. 1997. PC-ORD. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological

Data, Version 3.0. MjM Software Design, Gleneden Beach, OR. vi + 47 pp.

Natural Lands Trust. 2004. Burden Hill Preserve management plan. Natural Lands

Trust, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

62 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 17, No. 1

Olsson, H. 1979. Vegetation of the New Jersey Pine Barrens: A Phytosociological

Classification. Pp. 245 – 263, In R.T.T. Forman (Ed.). Pine Barrens: Ecosystem

and Landscape. Academic Press, New York, NY.

Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry. 2001. Manual for inventory of wild areas. Pennsylvania

Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Harrisburg, PA.

58 pp.

Robichaud, B., and M.F. Buell. 1973. Vegetation of New Jersey. Rutgers University

Press, New Brunswick, NJ. 340 pp.

US Department of Agriculture (USDA). 1969. Salem County (NJ) Soil Survey.

United States Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service, Washington,

DC in cooperation with New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, New

Brunswick, NJ. Issued May 1969, 86 pp. + maps.

Whittaker, R.H. 1979. Vegetational Relationships of the Pine Barrens. P. 322, In

R.T.T. Forman (Ed.). Pine Barrens: Ecosystem and Landscape. Academic Press,

New York, NY.

Woods, A.J., J.M. Omernik, and B.C. Moran. 2007a. Draft Level III and IV Ecoregions

of New Jersey [map]. US Environmental Protection Agency, National

Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Corvallis, OR. Available

online at ftp:ftp.epa.gov/wed/ecoregions/nj/nj_map.pdf. Accessed 2008.

Woods, A.J., J.M. Omernik, and B.C. Moran. 2007b. Level III and IV Ecoregions

of New Jersey. US Environmental Protection Agency, National Health and Environmental

Effects Research Laboratory, Corvallis, OR. 19 pp. Available online at

ftp: ftp.epa.gov/wed/ecoregions/nj/nj_eco_desc.pdf. Accessed 2008.