Predation on Dovekies by Goosefish over Deep Water in the

Northwest Atlantic Ocean

Matthew C. Perry, Glenn H. Olsen, R. Anne Richards, and Peter C. Osenton

Northeastern Naturalist, Volume 20, Issue 1 (2013): 148–154

Full-text pdf (Accessible only to subscribers.To subscribe click here.)

Access Journal Content

Open access browsing of table of contents and abstract pages. Full text pdfs available for download for subscribers.

Current Issue: Vol. 30 (3)

Check out NENA's latest Monograph:

Monograph 22

148 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 1

148

Predation on Dovekies by Goosefish over Deep Water in the

Northwest Atlantic Ocean

Matthew C. Perry1,*, Glenn H. Olsen1, R. Anne Richards2, and Peter C. Osenton1

Abstract - Fourteen Alle alle (Dovekie) were recovered from the stomachs of 14 Lophius

americanus (Goosefish) caught during winter and spring 2007–2010. All fish were caught in

gill nets set at depths of 85–151 m (276–491 ft) 104–150 km (65–94 mi) south of Chatham, MA.

Dovekies showed few signs of digestion by the fish, indicating recent capture. Post mortem revealed

no cause of mortality. Capture of birds by fish so far from shore and in deep water leads

to speculation that the birds were preyed on by Goosefish at or near the surface. Evidence from

electronic tagging of Goosefish suggests that Goosefish vertical migrations could bring them

into contact with Dovekies feeding offshore. If Goosefish are concentrated during onshoreoffshore

migrations and Dovekies are concentrated for feeding on prey patches, predation by

Goosefish on Dovekies could be episodically important.

While working in Nantucket, MA, in December 2007 on Seaducks (Tribe Mergini),

the authors heard from a fisherman (W. Blount, pers. comm.) that he had seen watermen

in Chatham, MA, remove seabirds from the stomachs of Lophius americanus Valenciennes

(Goosefish), a large lophiid anglerfish distributed widely in the northwest Atlantic

Ocean (Collette and Klein-MacPhee 2002). He further indicated that the birds may have

been Melanitta perspicillata L. (Surf Scoter), a common species in the Nantucket area

under study in the Atlantic Flyway (Perry et al. 2006), or Clangula hyemalis L. (Longtailed

Duck), a species being studied for feeding ecology (Perry 2012, White et al. 2009)

and for their daily “commute” from Nantucket Sound to the Atlantic Ocean (Davis 1997,

Perkins 1988). The Cape Cod Commercial Hook Fishermen’s Association in Chatham

was contacted and asked to notify watermen (especially deepwater gillnetters) to save for

examination any birds found in Goosefish.

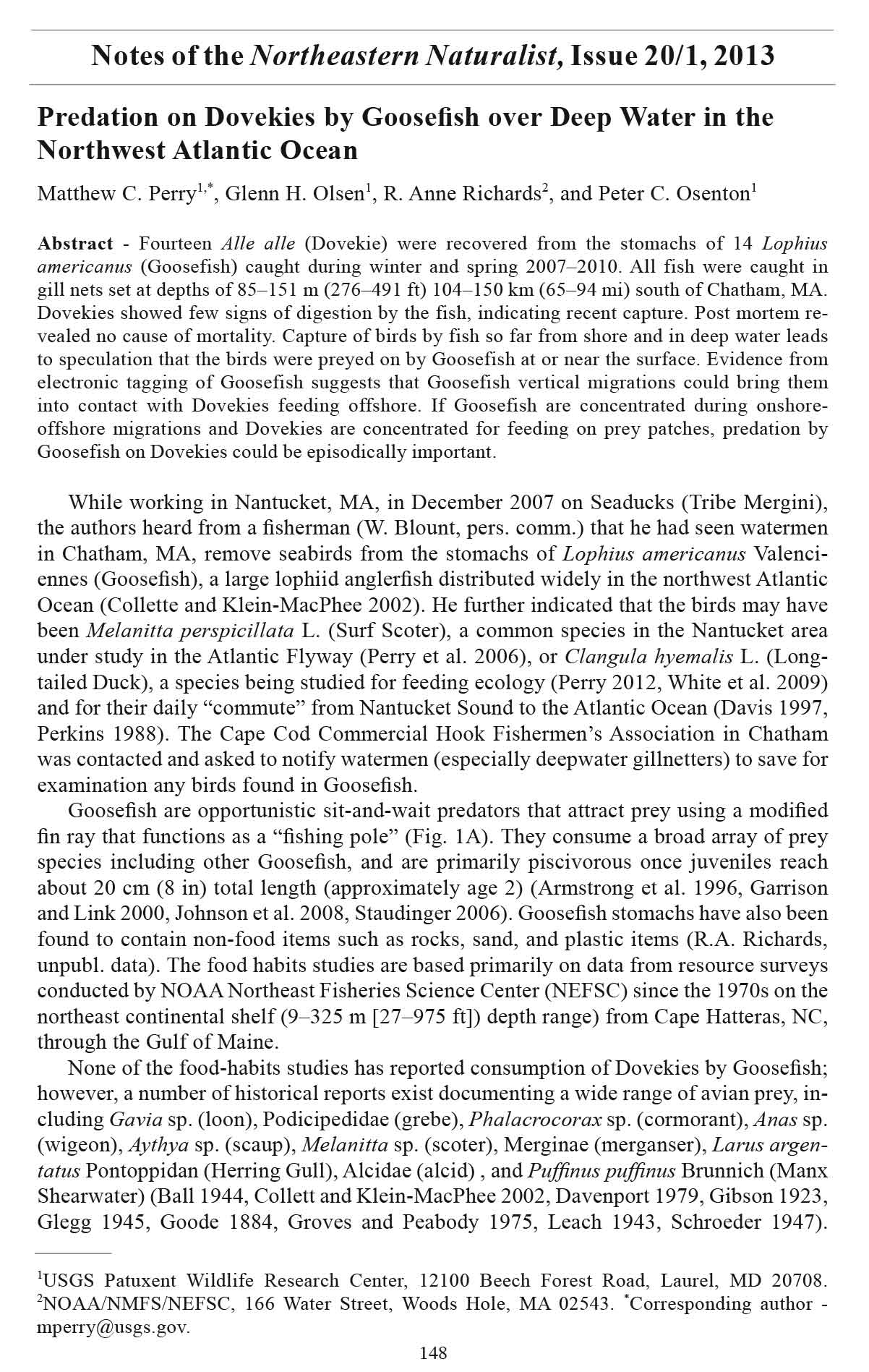

Goosefish are opportunistic sit-and-wait predators that attract prey using a modified

fin ray that functions as a “fishing pole” (Fig. 1A). They consume a broad array of prey

species including other Goosefish, and are primarily piscivorous once juveniles reach

about 20 cm (8 in) total length (approximately age 2) (Armstrong et al. 1996, Garrison

and Link 2000, Johnson et al. 2008, Staudinger 2006). Goosefish stomachs have also been

found to contain non-food items such as rocks, sand, and plastic items (R.A. Richards,

unpubl. data). The food habits studies are based primarily on data from resource surveys

conducted by NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) since the 1970s on the

northeast continental shelf (9–325 m [27–975 ft]) depth range) from Cape Hatteras, NC,

through the Gulf of Maine.

None of the food-habits studies has reported consumption of Dovekies by Goosefish;

however, a number of historical reports exist documenting a wide range of avian prey, including

Gavia sp. (loon), Podicipedidae (grebe), Phalacrocorax sp. (cormorant), Anas sp.

(wigeon), Aythya sp. (scaup), Melanitta sp. (scoter), Merginae (merganser), Larus argentatus

Pontoppidan (Herring Gull), Alcidae (alcid) , and Puffinus puffinus Brunnich (Manx

Shearwater) (Ball 1944, Collett and Klein-MacPhee 2002, Davenport 1979, Gibson 1923,

Glegg 1945, Goode 1884, Groves and Peabody 1975, Leach 1943, Schroeder 1947).

1USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, 12100 Beech Forest Road, Laurel, MD 20708.

2NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, 166 Water Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543. *Corresponding author -

mperry@usgs.gov.

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 20/1, 2013

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 149

Hunters have witnessed Goosefish rising to the surface of the wa ter and swallowing live

Herring Gulls whole (Groves and Peabody 1975).

Thirteen Dovekies collected from Goosefish stomachs in this study were examined

after donation from fishermen through the Cape Cod Commercial Hook Fishermen’s

Association (Table 1, Fig. 1). Two other Dovekies were reported by one of the same

gillnetters in December 2007, but were not submitted for examination. Dovekies and

Goosefish were frozen and later shipped for examination at USGS Patuxent Wildlife

Research Center. All fish were caught in gill nets set at depths of 85–151 m (276–491 ft)

104–150 km (65–90 mi) south of Chatham, MA (Table 1, Fig. 1). The nets were set for

3–6 days, with a mean soak time of 4.7 days. Three of the 14 Goosefish with Dovekies

were caught between early December and early January, and 9 were caught between late

March and early May (Table 1).

Eight of the 13 Dovekies were examined in a complete post-mortem, and no cause

of death could be determined. All 8 of the Dovekies had low body fat. However, size of

breast muscles (body condition index) was low in only 2 of the 8, indicating that it was

unlikely that the Dovekies had starved to death. Three of the 8 Dovekies had puncture

wounds in the skull, possibly inflicted by teeth of the Goosefish while the Dovekies were

being consumed.

Using traditional techniques (Perry and Uhler 1988), we examined 13 Dovekies for

food, of which 12 had no food in their gizzard and one Dovekie had a small particle of

an unknown crustacean. Of the Dovekies with no food, one had one small piece of quartz

grit and one had a 2-mm round ball of monofilament fishing line. There was no food or

other material in the gullet (esophagus and proventriculus). The mean weight of the gizzard

without food was 2.2 g (range = 1.5–3.4 g).

In the NOAA NEFSC food-habits data base, consumption of birds by Goosefish has

been seen very infrequently, although survey sampling is less intensive in shallow water

Table 1. Measurements of 13 Dovekies and 12 Goosefish caught 2008–2010, from boats homeported

in Chatham, MA.

Dovekie Goosefish

Net Capture Body Gizzard Body Body Body Body

Spec. soak location Depth wt. wt. lgth. wt. lgth. wdth.

No. Date days Lat. (N) Long.(W) (m) Age Sex (g) (g) (cm) (kg) (cm) (cm)

1 5/6/08 4 40°12.2' 70°02.4' 92 2.8 8.34A 81.3 38.1

2 12/5/08 41°36.9' 69°33.2' 111 180 3.3 4.54 76.2

3 12/5/08 41°36.9' 69°33.2' 111 200 2.1 2.27 50.8

4 3/27/09 105 km. s. of Nan. Is. 120 196 2.0 3.10 58.0A

5 4/1/09 6 40°03' 70°02' 151 162 2.0 3.30 59.3A

6 5/8/09 40°17.6' 70°03.4' 116 204 1.5 20.1 5.45 72.3A

7 1/10/10 3 40°21.4' 70°21.3' 85 4.25 72.0 30.0

8 3/28/10 145 km. s. of Cape Cod F 230 3.4 19.2

9 3/28/10 6 40°07.8' 70°02.9' M 196 1.9 19.4 9.08 83.7A

10 4/6/10 40°13.7' 70°03.6' 94 F 230 1.6 3.63 61.2 A

11 4/12/10 40°02.7' 69°56.0' 129 194 1.7 22.2 4.10 67.3

12 4/16/10 40°14.4' 70°22.1' 118 Ad F 208 2.1 21.9 5.51 70.9

13 4/24/10 4 40°04.9' 70°20.6' 126 M 206 1.7 22.6

14 4/25/10 5 40°07.3' 69°50.9' 96 Ad M 215 2.1 23.3 4.75 72.1

Mean 4.7 112 202 2.2 21.2 4.86 68.8 34.0

AMissing lengths and weights of Goosefish were derived from length-weight equations for Goosefish

(Wigley et al. 2003).

150 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 1

where predation by Goosefish on birds might be more common. Birds or feathers (not

identified to species) were found in 4 Goosefish out of total sample of approximately1200

stomachs examined during 1973–2010 (Table 2). These occurrences were all in the

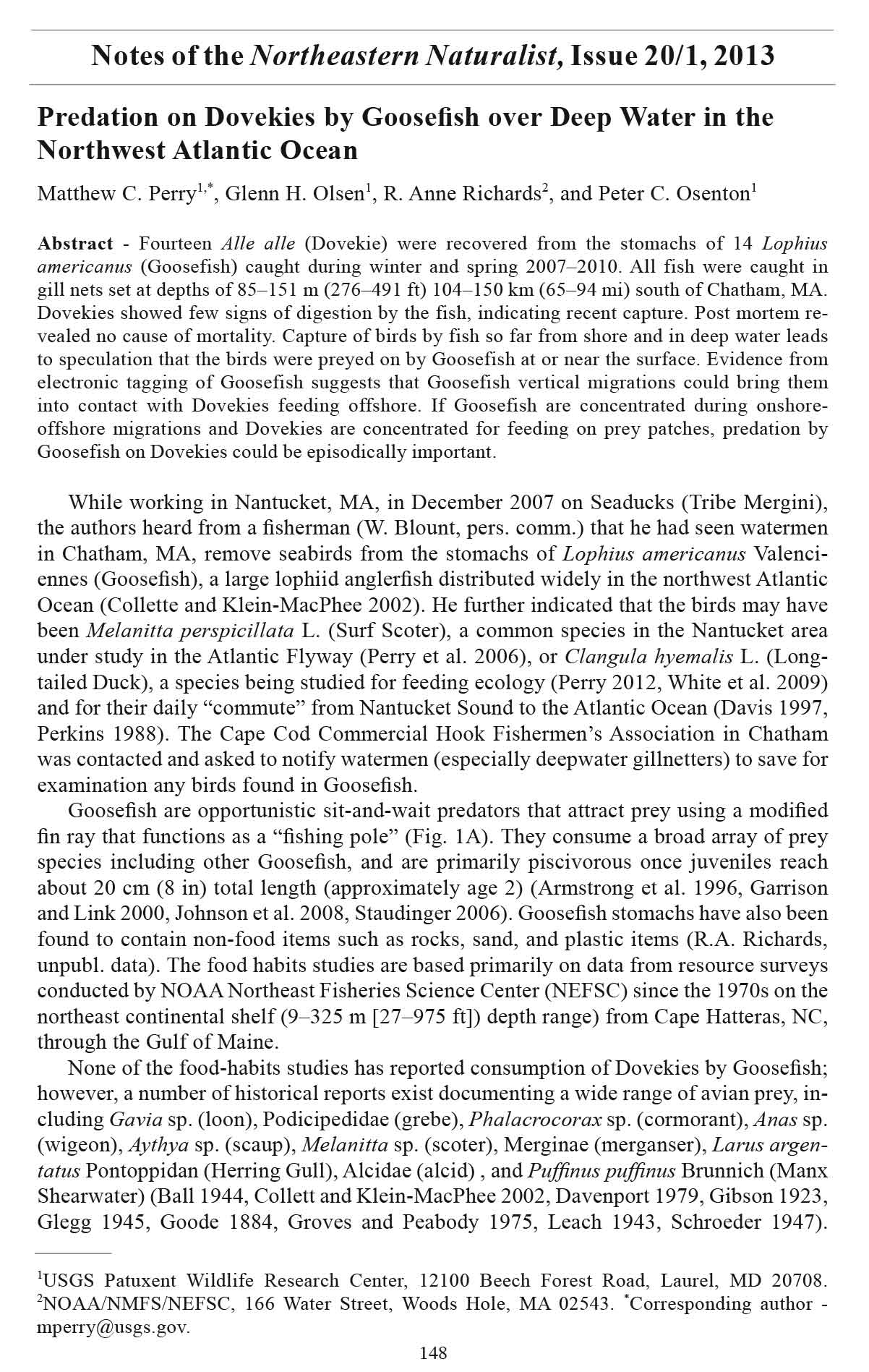

Figure 1. Goosefish with mouth open and Dovekie, which was removed from its stomach (A), and

3 Goosefish with 1 Dovekie removed from each fish (B).

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 151

spring, and ranged in location from near Cape Hatteras, NC, to the Gulf of Maine in

depths of 19–112 m (62–364 ft; Fig. 2). Two of the Goosefish containing feathers were

caught at the same survey station at 19 m (62 ft).

Table 2. Records of Goosefish captured with evidence of birds in stomachs, NOAA Northeast Fisheries

Science Center food-habits data base, 1973–2010.

Water Goosefish

Depth temp (°C) Length Weight Prey

Date Lat. Long. (m) Surface Bottom (cm) (kg) itemA Comments

4/23/1984 42°30' 65°51' 112 5.7 Bird Well digested

3/23/1999 40°45.7' 72°40.8' 19 5.0 4.6 19 0.15 Feathers

3/24/1999 40°45.7' 72°40.8' 19 5.0 4.6 23 0.19 Feathers

3/11/2006 36°26.1' 75°09.3' 35 9.5 9.4 67 4.36 Bird Well digested

ABird and feathers were not identified.

Figure 2. Locations where Goosefish that had consumed Dovekies were captured in this study

(filled circles). Two open circles represent two sites not represented by latitude and longitude (cf.

Table 1). Asterisks represent capture site of Goosefish with birds and feathers from NOAA Northeast

Fisheries Science Center food-habits data base, 1973–2010. Diamond indicates location of

Chatham, MA, on Cape Cod; arrow shows location of Nantucket Isl and.

152 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 1

We speculate that Dovekies are present in the Atlantic Ocean more than 100 km (62

mi) south of Cape Cod to feed on concentrations of zooplankton in the water (Nisbet et

al., in press). Zooplankton concentrations are a common food source for Dovekies in

other areas (Montevecchi and Stenhouse 2002). Other birds known to prey on zooplankton

in this region include Long-tailed Ducks, which have been found in the Nantucket

Island area (Fig. 2), with high numbers of the pelagic amphipod Gammarus annulatus S.I.

Smith in their gullet and gizzard (White et al. 2009). It has been hypothesized that most

of the food items (especially the amphipods) were obtained in the ocean during the day

before the ducks returned to Nantucket Sound at dusk. Zooplankton surveys have found

that Gammarid amphipods are seasonally abundant in the water column on Georges Bank

and Nantucket Shoals (Avery et al. 1996).

It seems unlikely that Dovekies, with maximum dive depths of 19–35 m (62–114 ft)

(Motevecchi and Stenhouse 2002) would encounter a benthic-dwelling fish in deep water.

Although Goosefish are known to feed on birds in shallow surface waters (Murdy et al.

1997), it seems unlikely that they would ascend 100 m (325 ft) or more to feed on birds.

However, Goosefish are known to rise off the bottom, possibly to ride currents during migration

periods in spring and fall or to spawn at the surface (Hislop et al. 2000, Laurenson

and Priede 2005, Rountree et al. 2008). Goosefish are highly opportunistic predators and

may feed while in the water column if the opportunity arises. The fresh state of digestion

of the consumed Dovekies suggests that they were consumed in the general vicinity

of the Goosefish capture location. Marine bird surveys indicate a substantial increase in

Dovekie abundance in shelf waters from Maine to North Carolina, especially near hydrographic

fronts over the last 30 years (T. White, College of Staten Island, Staten Island,

NY, pers. comm.; Nisbet et al., in press; Veit and Guris 2009).

Insight into Goosefish vertical migrations comes from two studies in which Goosefish

were tagged with electronic data storage tags (Richards et al. 2012, Rountree et al. 2008).

In both studies, Goosefish showed extensive vertical movements, which were frequent

during late fall and spring. Some of these movements brought Goosefish near or to the

surface. One Goosefish exhibited a vertical movement of 209 m (679 ft), (Rountree et al.

2008), which is greater than the maximum depth (151 m [491 ft]) where Goosefish with

Dovekies were collected in this study (Table 1). This finding indicates that predation by

Goosefish on birds at or near the water surface is plausible.

The vertical movements reported by Rountree et al. (2008) occurred primarily (81%)

between 0000 h and 1200 h and peaked at 0300 h and 1000 h. Visual observations of

Goosefish on the surface at night have been made by gillnet fishermen in deep ocean waters

south of Nantucket Island (J. Our, Captain of Miss Fitz, Chatham, MA, pers. comm.).

The night period is a time when Dovekies would most likely be sleeping on the water

surface. However, Goosefish typically cue in on movement to capture prey and may be

capturing Dovekies in early daylight hours when the birds begin to dive for mobile prey.

Future tagging of Goosefish with pop-off radio telemetry tags (L. Jordan, Microwave

Telemtery, Inc., Columbia, MD, pers. comm.) that transmit data to satellites would help

provide more information on vertical movements of Goosefish in regard to possible predation

on Dovekies.

The magnitude of fish predation on seabirds is poorly understood. Based on foodhabits

data from the Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s resource surveys, other fish

species that had birds or feathers in the stomach included: Squalus acanthias L. (Spiny

Dogfish), Leucoraja erinacea Mitchill (Little Skate), Clupea harengus L. (Atlantic

Herring), Gadus morhua L. (Atlantic Cod), Pollachius virens L. (Pollock), Urophycis

chuss Walbaum (Red Hake), and Hippoglossina oblonga Mitchill (Fourspot Flounder).

However, the incidence is very low, with only a total of 16 specimens (including 4

2013 Northeastern Naturalist Notes 153

Goosefish) found with evidence of predation on birds during 1973–2010. Undoubtedly,

the intensity of predation on birds by fishes varies temporally and geographically, but

may be episodically important as evidenced by the relatively large number of specimens

of Goosefish collected in this study that had consumed Dovekies.

Acknowledgments. Staff of the Cooperative Research Program of the Cape Cod

Commercial Hook and Fishermen’s Association (North Chatham, MA), especially E.

Brazer, Jr., P. Parker, M. Sanderson, and L. Slifka, were very helpful in storing and

mailing fish and birds for the project. Northeast Fisheries Science Center staff that assisted

included D. Palka and G. Shield. Gillnetters who assisted by providing fish with

birds included R. Crowell, D. Fenny, M. Linnell, G. Nickerson, J. Our, K. Tolley, R.

Tolley, and D. Vlacich. Massachusetts Audubon Society provided travel funds as part

of a project financed by Mineral Management Services. Assistance with Dovekie food

habits analyses and post-mortem examinations included C. Bermudez, C. Caldwell, M.

Gutierrez, and C. Kilchenstein. William Blount of Nantucket Island gave information

about the predatory nature of Goosefish. Technical advice and assistance were provided

by T. Allison, A. Berlin, L. Garrett, E. Holmes, L. Jordan, R. Kennedy, S. Perkins, B.

Truitt, R. Veit, J. Weske, T. White, and D. Ziolkowski.

Literature Cited

Armstrong, M.P., J.A. Musick, and J.A. Colvocoresses. 1996. Food and ontogenetic shifts in

feeding of the Goosefish, Lophius americanus. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science

18:99–103.

Avery, D.E., J. Green, and E.G. Durbin. 1996. The distribution and abundance of pelagic gammarid

amphipods on Georges Bank and Nantucket Shoals. Deep-Sea Research II 43(7–8):1521–1532.

Ball, S. 1944. Monkfish that ate a Red-breasted Mer ganser. Auk 61:477.

Collette, B.B., and G. Klein-MacPhee. 2002. Bigelow and Schroeder’s Fishes of the Gulf of Maine

(3rd Edition). Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC. 748 pp.

Davenport, L.J. 1979. Shag swallowed by Monkfish. Bulletin of the British Ornithological Club

72:77–78.

Davis, W.E., Jr. 1997. The Nantucket Oldsquaw flight: New England’s greatest bird show? Bird

Observer 25(1):16–22.

Garrison, L.P., and J.S. Link. 2000. Dietary guild structure of the fish community in the Northeast

United States continental shelf ecosystem. Marine Ecology Progress Series 202:231–240.

Gibson, L. 1923. “The replete angler”. Auk 40(1):120–121.

Glegg, W.E. 1945. Fishes and other aquatic animals preying on birds. Ibis 87:422–433.

Goode, G.B. 1884. The food fishes of the United States. Pp. 163–682, In G.B. Goode (Ed.). The

Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. US Commerce Fishery Report Section 1,

Part 3. Washington, DC.

Groves, S. and G. Peabody. 1975. Dead Herring Gull inside a Monkfish. Bird Banding 46(1): 76.

Hislop, J.R.G., J.C. Holst, and D. Skagen. 2000. Near-surface captures of post-juvenile anglerfish

in the northeast Atlantic: An unsolved mystery. Journal of Fish Biology 57:1083–1087.

Johnson, A.K., R.A. Richards, D.W. Cullen, and S.J. Sutherland. 2008. Growth, reproduction, and

feeding of large Monkfish, Lophius americanus. International Council for the Exploration of

the Sea Journal of Marine Science 65:1306–1315.

Laurenson, C.H., and I.G. Priede. 2005. The diet and trophic ecology of Angler Fish, Lophius

piscatorius, at the Shetland Islands, UK. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the

United Kingdom 85:419–424.

Leach, E.P. 1943. Finding of a leg band from a Manx Shearwater. Ibis 85:200.

Montevecchi, W.A., and I.J. Stenhouse. 2002. Dovekie (Alle alle). No. 701, In A. Poole and F. Gill

(Eds.). The Birds of North America. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and

the American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, DC.

154 Northeastern Naturalist Vol. 20, No. 1

Murdy, E.O., R.S. Birdsong, and J.A.Musick. 1997. Fishes of Chesapeake Bay. Smithsonian Institute

Press, Washington, DC. 324 pp.

Nisbet, I.C.T., R.R. Veit, S.A. Auer, and T.P. White. In press. Marine birds of the eastern USA and

the Bay of Fundy: Distribution, numbers, trends, threats, and management. Nuttall Ornithological

Monographs.

Perkins, S. 1988. Watching Oldsquaws. Sanctuary 28(3):23.

Perry, M.C. 2012. Foraging behavior of Long-tailed Ducks in a ferry wake. Northeastern Naturalist

19(1):135–139.

Perry, M.C., and F.M. Uhler. 1988. Food habits and distribution of wintering Canvasbacks (Aythya

valisineria) on Chesapeake Bay. Estuaries 11:57–67.

Perry, M.C., D.M. Kidwell, A.M. Wells, E.J.R. Lohnes, P.C. Osenton, and S.H. Altmann. 2006.

Characterization of breeding habitats for Black and Surf Scoters in the eastern boreal forest

and subarctic regions of Canada. Pp. 80–89, In A. Hanson, J. Kerekes, and J. Paquet (Eds.).

Limnology and Waterbirds 2003. The 4th Conference of the Aquatic Birds Working Group of

the Societas Internationalis Limnologiae (SIL). Canadian Wildlife Service Technical Report

Series No. 474. Atlantic Region, Sackville, NB, Canada. xii + 202 pp.

Richards, R.A., J. Grabowski, G. Sherwood, L. Alade, and C. Bank. 2012. Archival tagging study

of Monkfish, Lophius americanus. Final Report to the Northeast Consortium, Award No. 09-

042. Available online at http://www.northeastconsortium.org/ProjectView.pm?id=15740&on_

update=OQrefresh. Accessed 27 March 2012.

Rountree, R.A., J.P. Gröger, and D. Martins. 2008. Large vertical movements by a Goosefish,

Lophius americanus, suggests the potential of data storage tags for behavioral studies of benthic

fishes. Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology 41(1 ):73–78.

Schroeder, W.C. 1947. Notes of the diet of Goosefish, Lophius americanus. Copeia 201.

Staudinger, M.D. 2006. Seasonal and size-based predation on two species of squid by four fish

predators on the Northwest Atlantic continental shelf. Fishery Bulletin 104:605–615.

Veit, R.R., and P.A. Guris. 2009. Recent increases in alcid abundance in the New York Bight and

New England Waters. New Jersey Birds 34:83–87.

White, T.P., R.R. Veit, and M.C. Perry. 2009. Feeding ecology of Long-tailed Ducks, Clangula

hyemalis, wintering on the Nantucket Shoals. Waterbirds 32(2):293–299.

Wigley, S.E., H.M. McBride, and N.J. McHugh. 2003. Length-weight relationships for 74 fish

species collected during NEFSC research vessel bottom trawl surveys, 1992–1999. NOAA

Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-171. Woods Hole, MA. 26 pp.