N15

2015 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 22, No. 3

J.J. Newhard

Identification and Location of Testes in the Invasive Channa

argus Cantor (Northern Snakehead)

Joshua J. Newhard*

Abstract - Channa argus (Northern Snakehead) has been established in the Potomac River since at

least 2004. Although ovaries of females have previously been discovered, to date, no testes had been

confirmed in males from the Potomac River or any other North American waterbody. Dissection of

individual Northern Snakeheads and subsequent histology confirmed discovery of testes in males

taken from Quantico Creek, VA. Our discussion includes implications of this finding and methods for

properly dissecting males to find testes.

Introduction. Channa argus Cantor (Northern Snakehead) was first discovered in

the Potomac River watershed in 2004 (Odenkirk and Owens 2005). Since its discovery,

Northern Snakehead has expanded throughout much of the watershed, covering over 193

river-km (Fuller et al. 2014). Moreover, the species has invaded several major waterbodies

along the eastern US coast including tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware

Bay watersheds (Fuller et al. 2014). Due to the ability of Northern Snakehead to rapidly

colonize new areas and to potentially impact ecosystems where it is found, researchers have

been studying this species in its new environment. Some research has focused on habitat

preferences (Lapointe et al. 2010, 2013), while other work has focused on interactions between

Northern Snakehead and its potential prey and/or competitors (Love and Newhard

2012, Saylor et al. 2012). However, little research has been completed on the reproductive

nature of Northern Snakehead, especially in regards to sexual differentiation (see Gascho

Landis et al. 2011). In fact, one of the research priorities of the national control and management

plan for members of the snakehead family is to determine methods for sexing

snakeheads, including histology of testes (ANSTF 2014). Currently, it is known that the

reproductive potential of Northern Snakehead is relatively high, with a single female generally

producing about 40,000 eggs but capable of producing up to 100,000 eggs (USFWS

2014). Limited information is available about the ova of Northern Snakehead, and no testes

had been described from Northern Snakehead in North American waters to date.

Observations. We captured 8 Northern Snakeheads via boat electrofishing from Quantico

Creek, VA (Potomac River) on 5 August 2014. Following acceptable standard operating

procedures, we placed all fish on ice upon capture for transport to the lab for stomachcontent

analysis and dissection. Historically, sex of mature fish was determined based on

the presence or absence of egg-laden ovaries (J.J. Newhard, pers. observ.). If no ovaries

were found, a fish was classified as a male even though no testes were positively identified.

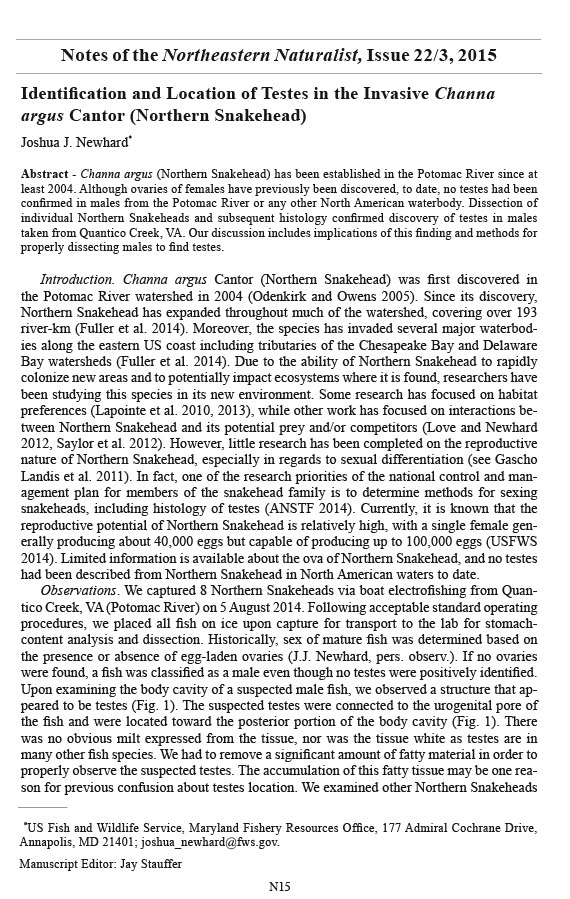

Upon examining the body cavity of a suspected male fish, we observed a structure that appeared

to be testes (Fig. 1). The suspected testes were connected to the urogenital pore of

the fish and were located toward the posterior portion of the body cavity (Fig. 1). There

was no obvious milt expressed from the tissue, nor was the tissue white as testes are in

many other fish species. We had to remove a significant amount of fatty material in order to

properly observe the suspected testes. The accumulation of this fatty tissue may be one reason

for previous confusion about testes location. We examined other Northern Snakeheads

*US Fish and Wildlife Service, Maryland Fishery Resources Office, 177 Admiral Cochrane Drive,

Annapolis, MD 21401; joshua_newhard@fws.gov.

Manuscript Editor: Jay Stauffer

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 22/3, 2015

2015 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 22, No. 3

N16

J.J. Newhard

Figure 1. Dissected view of a male Northern Snakehead collected from Quantico Creek, VA. Note

the location of the structure positively identified as testes in the black circle (indicated by arrows).

Photograph by Joshua Newhard, US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Figure 2. Stained gonadal tissue from testes of a male Northern Snakehead collected from Quantico

Creek, VA. Darker dots are spermatozoa. Photograph by Joe Marcino, Maryland Department of

Natural Resources.

N17

2015 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 22, No. 3

J.J. Newhard

collected at Quantico Creek for the presence of testes. In all, we found structures tentatively

identified as testes in 5 fish ranging in size from 502 to 871 mm total length (TL). The remaining

3 fish were females or sexually immature (less than 150 mm TL).

In order to confirm that the observed structure was testes, we took tissue samples and

preserved them in 10% formalin. We sent tissue samples from an individual of 591 mm TL

to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MDDNR) Coopera tive Oxford Laboratory

(Oxford, MD) for histological analysis whereby subsamples of tissue were removed,

mounted, stained, and viewed under a microscope. Upon examination, spermatozoa were

observed in the gonad (Fig. 2), thus confirming the structure as testes.

Discussion. Our report is the first known positive identification of testes in Northern

Snakehead from North America. While it previously was accepted that males and females

existed in the Potomac River population, only the absence of ovaries was considered

as identification of a male fish. Researchers can now positively identify male Northern

Snakeheads. This information can aid in determining sex ratios of a population, improve

population assessments, and facilitate investigations into potential sexually dimorphic behaviors

or features. For example, body size may differ between males and females. To date,

the largest Northern Snakehead collected by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (892 mm

TL) was previously identified as a male (based on absence of ovaries), whereas the largest

female collected was 782 mm TL (J.J. Newhard, unpubl. data). In addition, 1 fish from this

study was positively identified as male (testes were observed) at 871 mm TL, suggesting

that males may grow to larger sizes than females. Now that males can be confirmed, study of

sexual differences of Northern Snakeheads can be properly assessed, thus meeting a priority

research goal identified in the national snakehead management pl an (ANSTF 2014).

The following protocol can be followed to find testes in a Northern Snakehead. The first

cut should begin behind the anus and urogenital opening and extend posteriorly for 50 mm.

Care should be taken not to cut away any structures near the urogenital opening. Then a

vertical cut should be made toward the dorsum of the fish. The incision can then proceed

toward the anterior portion of the fish toward the operculum. The final cut can come down

ventrally and end near the base of the pectoral fin, creating a flap than can be removed if

desired. If present, the testes will be attached to the urogenital opening and protrude posteriorly

into the body cavity. There may be fatty tissue surrounding the testes that will need

to be carefully removed for specimen examination.

Acknowledgments. I’d like to thank J. Marcino of MDDNR for his histological analysis

of tissue samples. I thank 2 anonymous reviews whose comments greatly improved this

note, and J. Love for his assistance in organizing tissue delivery. I am grateful to I. Park and

K. Clowes for their help in collecting the Northern Snakeheads from Quantico Creek.

Literature Cited

Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force (ANSTF). 2014. National control and management plan for

members of the snakehead family (Channidae). Available online at http://www.anstaskforce.gov/

Species%20plans/SnakeheadPlanFinal_5-22-14.pdf. Accessed November 2014.

Fuller, P.F., A.J. Benson, and M.E. Neilson. 2014. Channa argus. USGS nonindigenous aquatic

species database, Gainesville, FL. Available online at http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.

aspx?speciesID=2265. Accessed November 2014.

Gascho Landis, A.M., N.W.R. Lapointe, and P.L Angermeier. 2011. First record of a Northern Snakehead

(Channa argus Cantor) nest in North America. Northeastern Naturalist 17:325–335.

Lapointe, N.W.R., J.T. Thorson, and P.L. Angermeier. 2010. Seasonal meso- and microhabitat selection

by the Northern Snakehead (Channa argus) in the Potomac River system. Ecology of Freshwater

Fish 19:566–577.

2015 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 22, No. 3

N18

J.J. Newhard

Lapointe, N.W.R., J.S. Odenkirk, and P.L. Angermeier. 2013. Seasonal movement, dispersal, and

home range of Northern Snakehead Channa argus (Actinopterygii, Perciformes) in the Potomac

River catchment. Hydrobiologia 709:73–87.

Love, J.W., and J.J. Newhard. 2012. Will the expansion of Northern Snakehead negatively affect the

fishery for Largemouth Bass in the Potomac River (Chesapeake Bay)? North American Journal of

Fisheries Management 32:859–868.

Odenkirk, J., and S. Owens. 2005. Northern Snakeheads in the tidal Potomac River system. Transactions

of the American Fisheries Society 134:1605–1609.

Saylor, R., N. Lapointe, and P. Angermeier. 2012. Diet of non-native Northern Snakehead (Channa

argus) compared to three co-occurring predators in the lower Potomac River, USA Ecology of

Freshwater Fish 21:443–452.

US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2014. Northern Snakehead fact sheet. Available online at

http://www.fws.gov/northeast/marylandfisheries/reports/Snakehead Accessed November 2014.