2015 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 22, No. 4

N24

J. Alcock

A Note on the Mating Behavior of Empis gulosa Coquillett

(Diptera: Empididae)

John Alcock*

Abstract - I present here the first description of the mating behavior of the empidid fly Empis gulosa.

Males of this predatory species appear to provide their copulatory partners with a nuptial gift in the

form of a small insect that the female consumes while mating. In northern Virginia, copulations occur

in late April and early May primarily in the late afternoon or evening.

Introduction. The empidid fly Empis gulosa Coquillett belongs to the subgenus Enoplempis

Bigot, a diverse North American group that exhibits an interesting array of mating

behaviors (depending on the species) from the presentation of small silken packets with or

without prey inside the “balloons” to unwrapped prey as nuptial gifts (Sinclair et al. 2013).

Although E. gulosa has a fairly wide distribution from the northeastern US to Alabama,

there have been no published reports on its mating behavior to date (Sinclair et al. 2013).

Here I provide a brief account of aspects of the fly’s mating behavior observed at a site in

northern Virginia, a state from which the species had not been collected previously (Sinclair

et al. 2013).

Materials and Methods. I observed the flies between 29 April 2015 and 5 May 2015

on Monterey Farm near Marshall, VA, at a site in an unmowed strip near a small stream

(38o52'19.65''N, 77o54'24.22"W). About seventy-five 1-m-tall dried stalks of Apocynum

cannibinum L. (Hemp Dogbane) occupied an area ~1 1 m x 5.5 m at the study site. Near -

by and also in the unmowed strip, there were a number of dried ~1-m-tall grass stalks

standing well above the surrounding living grass. Pairs of flies flew to and landed on

the Hemp Dogbane and grass stalks where I photographed and coun ted them at different

times of the day.

I took photographic vouchers of the prey that the male offered the female. In some cases,

I pulled the prey from the female and made a collection for lat er identification.

I performed some simple experiments in which I carefully removed the prey on which

the female was feeding. This treatment did not always result in the immediate departure of

the mating flies, and I was able to observe the effect of an absence of a nuptial-prey gift on

the behavior of the female.

Results. After counting as many as 9 mating pairs of E. gulosa at the study site on

the evening of 29 April, I initiated haphazard censuses (26 total) with at least an hour

between counts on the following 4 days (30 April–May 3). These data enabled me to

determine when the flies began to mate and when the maximum number of pairs was

present on any given day. I observed single pairs as early as 1100–1215 EDT on 3 of

these days, but I recorded the vast majority of matings (44/54; 84%) between 1600–1900

EDT, with maxima ranging from 4 to 12 on the 4 days with more than 1 mating. On 4

May and 5 May, I observed only single mating pairs and thereafter, saw none. Although

I did not observe aerial-mating swarms, they might have been present nearby but out of

sight or high above the unmowed strip.

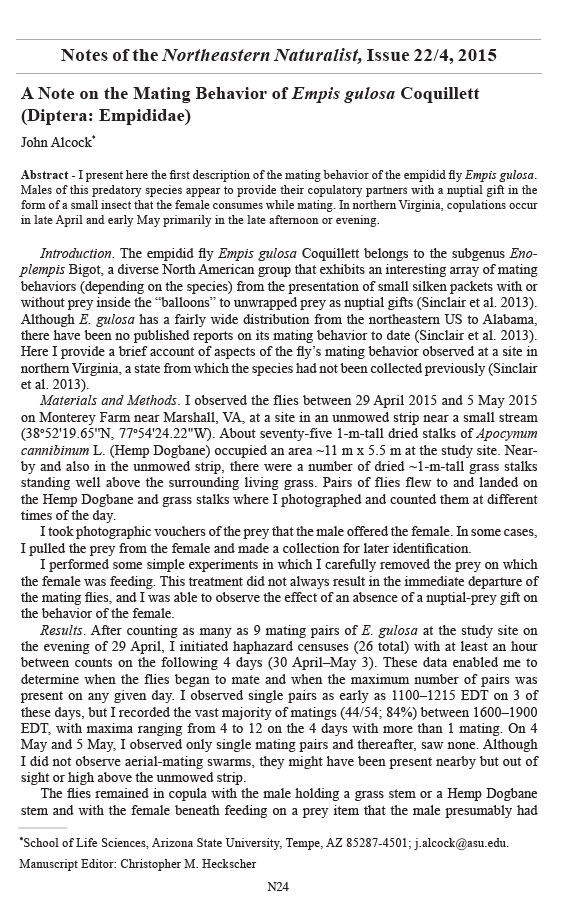

The flies remained in copula with the male holding a grass stem or a Hemp Dogbane

stem and with the female beneath feeding on a prey item that the male presumably had

*School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4501; j.alcock@asu.edu.

Manuscript Editor: Christopher M. Heckscher

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 22/4, 2015

N25

2015 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 22, No. 4

J. Alcock

transferred to her (Fig. 1). Based on my collected specimens and photographed material,

the prey consumed were mostly small flies including representatives from the Bibionidae

(n = 16), Tipulidae (n = 2), Syrphidae (n = 1), and Empididae (females of E. gulosa, n = 3).

Small Trichoptera (caddisflies) were also taken on occasion (n = 2), as were several unidentifiable

items.

I observed 2 instances when a female dropped the husk of a presumably fully consumed

nuptial gift after which a brief struggle ensued between male and female, followed by separation

of the pair in less than 2 minutes. The 6 times I experimentally removed prey from

the females that did not result in the immediate departure of the disturbed flies, there was a

short struggle between the 2 partners followed by their separat ion.

Discussion. The Empididae exhibit a wide range of mating systems (Chvála 1976, Cumming

1994, Downes 1970). In some species, mating occurs on the ground. In others, males

form aerial swarms visited by receptive females who receive a nuptial gift, generally a prey

item, prior to mating. A sex-role reversal occurs in some other species in which females

form swarms that are visited by prey-bearing males who choose mates from the group before

providing the selected individuals with a nuptial gift (e. g., Funk and Tallamy 2000).

The fly E. gulosa appears to be a member of the non-sex-role-reversed group, given

that females lack the highly modified legs with pinnate scales and/or eversible pleural sacs

characteristic of the sex-role reversed empidids (Cumming 1994). Unfortunately, I did not

observe the interactions that occur during the presumed transfer of the prey item from the

male to the female. Despite my attempts to locate the flies prior to their mating, I was unable

to do so, perhaps because I happened to observe the flies at the very end of their mating

season and so had only a few days in which to search for them in sites adjacent to the place

where copulation took place. Nevertheless, it is almost certain males give nuptial gifts—in

Figure 1. A pair of Empis gulosa mating while the male grasps an Apocynum cannibinum (Hemp Dogbane)

stem and the female feeds on a presumed nuptial gift cons isting of a syrphid fly.

2015 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 22, No. 4

N26

J. Alcock

the form of a wide range of insect prey (including members of E. gulosa)—to the female.

The presentation of nuptial gifts is a rather common phenomenon among insects in general

(Gwynne 2008, Lewis and South 2012) and empidids in particular (Chvála 1976, Cumming

1994). Moreover, other studies of nuptial-gift giving have indicated that the duration of mating

is apparently contingent upon the female’s access to the food received (Gwynne 2008,

Thornhill 1976). Once a female has consumed a food item, she apparently drops the emptied

prey and separates from the male after a short interaction between the two in which the male

appears to resist the departure of the female. My observations confirmed this finding.

Although much more remains to be learned about E. gulosa, the results of my study

provide some information about the mating behavior of this member of an intriguing group

of flies.

Acknowledgments. Dr. Jeffrey Cumming and Dr. Bradley Sinclair of the Canadian National

Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Ottawa, ON, Canada, very helpfully

provided the identification of Empis gulosa and constructively reviewed an initial draft of

this note.

Literature Cited

Chvála, M. 1976. Swarming, mating, and feeding habits in Empididae (Diptera), and their significance

in evolution of the family. Acta Entomologica Bohemoslovaca 73:353–366.

Cumming, J.M. 1994. Sexual selection and the evolution of Dance Fly mating systems (Diptera: Empididae;

Empidinae). The Canadian Entomologist 126:907–920.

Downes, J.A. 1970. The feeding and mating behavior of the specialized Empidinae (Diptera): Observations

on four species of Rhamphomyia in the high arctic and a general discussion. The Canadian

Entomologist 102:769–791.

Funk, D.H., and D.W. Tallamy. 2000. Courtship-role reversal and deceptive signals in the Long-tailed

Dance Fly, Rhamphomyia longicauda. Animal Behavior 59:411–421.

Gwynne, D. 2008. Sexual conflict over nuptial gifts in insects. Annual Reviews of Entomology

53:83–101.

Lewis, S., and A. South. 2012. The evolution of animal nuptial gifts. Advances in the Study of Behavior

44:53–97.

Sinclair, B.J., S.E. Brooks, and J.M. Cumming. 2013. Revision of the Empis subgenus (Enoplempis)

Bigot east of the Rocky Mountains (Diptera: Empididae). Zootaxa 3736:401–456.

Thornhill, R. 1976. Sexual selection and nuptial feeding behavior in Bittacus apicalis (Insecta: Mecoptera).

American Naturalist 110:529–548.