N35

2017 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 24, No. 4

C. Slusarczyk Jr. and A.W. Jones

Observations of a Killdeer Nest with Possible Simultaneous

Polygamy

Chuck Slusarczyk Jr.1 and Andrew W. Jones2,*

Abstract - Shorebirds (Order Charadriiformes) exhibit a wide variety of breeding systems, and have

been the subject of extensive studies on the evolution of these systems. Nevertheless, there are many

monogamous species within this clade. Previous studies of Charadrius vociferus (Killdeer) have

shown that they are monogamous, with only a single documented variation (serial polyandry). We

report observations at a nest that contained 7 eggs (typical nests have 4 eggs). The nest was being attended

by 3 adults, and it successfully fledged young. This is the first documented Killdeer nest with

possible simultaneous polygamy.

Breeding systems vary between species of birds as a result of various life-history

tradeoffs and evolutionary conflicts between the sexes (Thomas et al. 2007). Although

birds display a wide diversity of breeding systems, the majority of species are monogamous.

However, examples of all forms of polygamy have been documented in avian

species (Oring 1982). The breeding systems of shorebirds (Order Charadriiformes, often

called waders) are well studied and they include examples of all of the breeding system

types. Additionally, the various forms of polygamy are more commonly seen within this

order than in other avian orders (Thomas et al. 2007). There are conflicting explanations

for this situation. Initial hypotheses on breeding-system variation in shorebirds focused

on the fact that most species have fixed-size clutches. Most Northern Hemisphere shorebirds

lay 4-egg clutches. Oring (1986) reviewed the literature on avian polyandry, noting

that a fixed-size clutch may be an ancestral condition that leads to polyandry as individuals

try to maximize their own reproductive output; however, Thomas et al. (2007)

suggested flaws in this explanation.

Charadrius vociferus L. (Killdeer) is a familiar North American shorebird species that

nests in open fields, including many human-modified landscapes. They are known to be monogamous,

with no documentation of extra-pair copulations (Jackson and Jackson 2000).

Here we present observations at a nest with 7 eggs that was being attended by 3 adults.

On 2 July 2016, C. Slusarczyk Jr. discovered a Killdeer nest with 7 eggs at Burke Lakefront

Airport near downtown Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, OH. The nest was being tended

by 3 adult birds. Slusarczyk continued to observe the nest through 31 July 2016 when there

were no more eggs, nor nestlings, present. Typically, Killdeer are socially monogamous

(the male and female demonstrate a pair bond, though they may also seek extra-pair copulations),

and, like all shorebirds, their first clutch of the year has 4 eggs (Jackson and Jackson

2000). Killdeer construct a nest as a scrape in an open field, typically lined with pebbles

and other black and white debris, which helps camouflage the eggs (Jackson and Jackson

2000). This nest was situated in a wide-open graveled area ~50 m from the east wall of an

airport hangar, in a fully sunlit location and on level ground. It was constructed primarily

of pea- to marble-sized gravel, with the larger pieces placed towards the periphery of the

scrape. Overall, the nest was ~0.33 m in circumference and well camouflaged. The field

12154 Thurman Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44113 2Department of Ornithology, Cleveland Museum of

Natural History, 1 Wade Oval Drive - University Circle, Cleveland, OH 44106. *Corresponding author

- ajones@cmnh.org.

Manuscript Editor: Daniel M. Keppie

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 24/4, 2017

2017 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 24, No. 4

N36

C. Slusarczyk Jr. and A.W. Jones

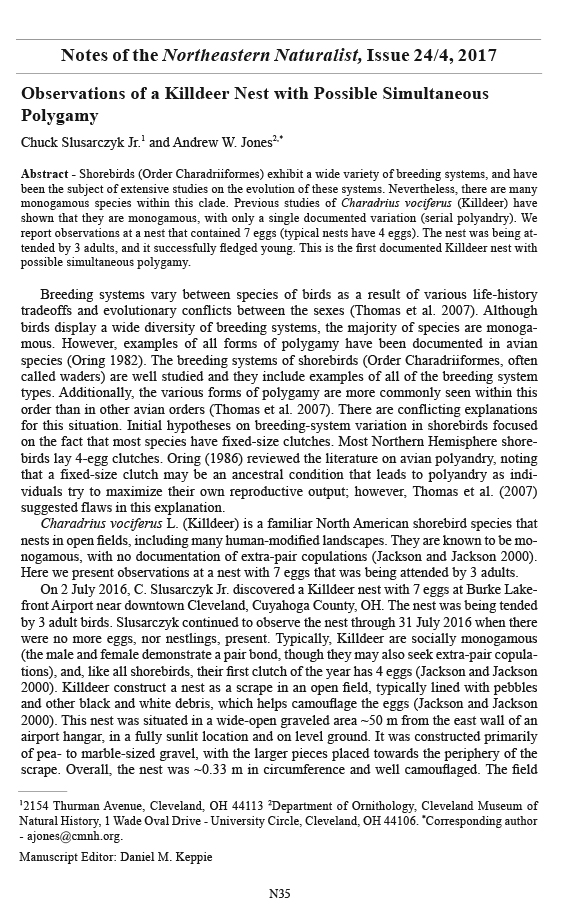

Figure 1. Killdeer nest with 7 eggs at Burke Lakefront Airport in Cleveland, Cuyahoga Co., OH.

The nest already had 7 eggs when first discovered. (A) Initially, the outer eggs were not neatly arranged;

narrow ends of the eggs are oriented in haphazard directions. (B) After 4 July, the eggs were

configured with 1 egg in the center and the other 6 arranged around it with their narrow ends facing

the middle egg. Eggs remained in this configuration during successive observations. Both photos by

Chuck Slusarczyk Jr. (left on 2 July 2016, right on 23 July 2016).

where the nest was constructed was a mosaic of bare gravel and low plants. The nest itself

was in an area where low-growing Trifolium repens L. (White Clover), Plantago lanceolata

L. (Narrowleaf Plantain), and Plantago major L. (Broadleaf Plantain) were dominant and a

few grasses were present. Two sheets of weathered commercially manufactured 1.2 x 2.4-m

(4 x 8-ft) plywood lay within 2 m of the nest. Burke Lakefront Airport has a high density of

breeding pairs (C. Slusarczyk Jr., pers. observ.). Chuck Slusarczyk Jr. also observed 5 other

nests within ~250 m that had the expected 4-egg complement.

The nest already contained 7 eggs when discovered (Fig. 1A). We observed 3 adults

displaying in close association with the nest (within 3 m). The eggs were arranged in a

circle of 6 with 1 additional egg in the center; they remained in this orientation on all successive

visits. Initially, the outer 6 eggs were poorly arranged, with the pointed ends in

various directions. By 4 July, the outer eggs were oriented in the more typical arrangement

for shorebirds, with all points oriented towards the center of the nest (Fig. 1B).

In all successive 15 observations, all 3 birds performed distraction displays within 5 m

of the nest. Shorebirds, and particularly Killdeer, are well known for their various behaviors

to redirect potential predators away from their nests, including brooding a site where there

are no eggs, feigning a wing injury while calling, and running aggressively at predators

with body feathers erect and both wings and tail spread open to appear larger (Jackson and

Jackson 2000). C. Slusarczyk Jr. observed all of these behaviors, and kept observations as

short as possible to avoid undue disturbance while documenting this unusual nest.

Killdeer have a 22–29-d incubation period (Jackson and Jackson 2000). Without knowing

the date that the eggs were laid or when incubation began, C. Slusarczyk Jr. kept a

careful watch on the eggs almost daily in late July (daily visits were not possible due to access

issues at this site). On 25 July, the 3 adults became more vocal, their displays became

more frantic, and they approached within 5 m of the observer. On 27 July, 2 Killdeer chicks

were visible scurrying into the clover, and 2 additional freshly hatched birds were resting on

the remaining 3 eggs while 3 adults vocalized and displayed nearby. No additional observations

were made until 30 July 2016, when a single egg remained and multiple (uncountable)

young were in the area. On 31 July 2016, no eggs remained.

N37

2017 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 24, No. 4

C. Slusarczyk Jr. and A.W. Jones

Jackson and Jackson (2000) reviewed the literature on Killdeer and noted several reports

of 5 or 6 eggs in a nest, and a single report of 8 eggs. They overlooked a report by Mundahl

et al. (1981), which documented a Killdeer nest with 20 eggs. The 2 adults associated

with the latter nest were marked with ink on the feathers. The marked birds were observed

copulating, and several eggs were tested and shown to be fertile. No other individual adult

Killdeer were observed at the nest, and the authors suggested that the 20 eggs were all laid

by a single female. A single adult could only incubate ~6 eggs and, in this case, none of the

eggs hatched. Brunton (1988) studied Killdeer in Michigan, and followed a pair that nested

successfully. The day after their 4 eggs hatched, the female was observed mating with another

male on an adjacent territory, and 4 days later, researchers discovered a nest with 3

eggs. This situation is an example of sequential polyandry; the female did not associate

with both males at the same time. In the nest we report here, the 3 adults were not banded

or otherwise marked. We did not directly observe mating and we did not collect the birds;

thus, we do not know whether there were 2 females laying eggs in the single nest, or if two

males were socially bonded to a single female. Both possibilities are plausible, considering

the fecundity of the female in the Mundahl et al. (1981) report and polyandrous behavior

reported in Brunton (1988).

Thomas et al. (2007) advocate incorporating the availability of potential mates into

expanding our understanding of breeding-system evolution. In the present case, Killdeer

were very abundant (but not counted), and access to a large pool of possible mates may

have played a significant role in this possible polygamous nesting. For future studies of

intraspecific variation in mating systems of shorebird species and other clades thought to

be socially monogamous, incorporating DNA sampling may reveal much more flexibility in

breeding systems than is presently documented.

Acknowledgments. A. Jones was supported by the William A. and Nancy R. Klamm

Endowment at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Literature Cited

Brunton, D.H. 1988. Sequential polyandry by a female Killdeer. Wilson Bulletin 100:670–672.

Jackson, B.J., and J.A. Jackson. 2000. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus). In P.G. Rodewald (Ed.).

The Birds of North America. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. Available online at https://

birdsna-org.bnaproxy.birds.cornell.edu/Species-Account/bna/species/killde/. Accessed 5 February

2017.

Mundahl, J.T., O.L. Johnson, and M.L. Johnson. 1981. Observations at a 20-egg Killdeer nest. The

Condor 83:180–182.

Oring, L.W. 1982. Avian mating systems. Pp. 1–92, In D.S. Farner, J.R. King, and K.C. Parkes (Eds.).

Avian Biology. Volume VI. Academic Press, New York, NY. 490 pp.

Oring, L.W. 1986. Avian polyandry. Current Ornithology 3:309–351.

Thomas, G.H., T. Székely, and J.D. Reynolds. 2007. Sexual conflict and the evolution of breeding

systems in shorebirds. Advances in the Study of Behavior 37:279–342.