N9

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

G.R. Graves

Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii) in a Monoculture

of Invasive Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

Gary R. Graves*

Abstract - This paper reports the first record of a territorial Limnothlypis swainsonii (Swainson’s

Warbler) associated with the invasive Reynoutria japonica (Japanese Knotweed). The observation

adds to a growing body of literature documenting rapid behavioral adaptation to novel habitats in this

globally rare warbler.

Limnothlypis swainsonii Audubon (Swainson’s Warbler), reaches its highest breeding

abundance in early-successional hardwood forests on the coastal plain of the southeastern

US (Graves 2002, Graves and Tedford 2016, Meanley 1971). It also breeds in a bewildering

variety of other habitats (Anich et al. 2010) that provide the essential common denominators

of high understory-stem density, visual screening, and copious leaf litter (Graves 1998,

Graves and Tedford 2016). Populations in the core breeding range have exhibited rapid

behavioral adaptation to novel habitats, extending to the colonization of young Pinus (pine)

plantations (Bassett-Touchell and Stouffer 2006, Carrie 1996, Graves 2015, Henry 2004).

Peripheral breeding populations of Swainson’s Warbler in the Appalachian Mountains

occur in Rhododendron (rhododendron) and Kalmia (laurel) thickets and mixed mesophytic

cove forest from northern Georgia to West Virginia (Brooks and Legg 1942, Lanham and

Miller 2006, Legg 1946, Sims and DeGarmo 1948). Virtually nothing is known about the

quantitative patterns of habitat selection or the behavioral responses of montane populations

to anthropogenic habitats and invasive non-native plants. Here, I report the first record

of a territorial Swainson’s Warbler associated with the invasive Reynoutria japonica Houtt.

(Japanese Knotweed, hereafter, Knotweed) in Mingo County, WV. This plant is more widely

known in literature as Fallopia japonica (Houtt.) Ronse Decr. or Polygonum cuspidatum

Siebold and Zucc. (Del Tredici 2017).

Classified as one of the 100 worst invasive alien species in the world (Lowe et al. 2004),

Knotweed was introduced in New York as a garden ornamental before 1870 (Barney 2006,

Del Tredici 2017). By 2000, it had been collected in 71% of the counties in New York,

Pennsylvania, Maryland, and the New England states (Barney 2006), and had also escaped

cultivation at numerous sites within the breeding range of Swainson’s Warbler from West

Virginia to Louisiana. The perennial Knotweed readily invades riparian corridors, spreads

rapidly through rhizomatous growth, and frequently forms dense monocultures that can

dominate light gaps and invade mowed rights-of-way (Aguilera et al. 2010, Barney 2006,

Hollingsworth and Bailey 2000). Knotweed stands commonly exhibit high densities (27–48

stems/m2) (Maurel et al. 2013, Wilson et al. 2017). The semi-woody stems die back to

ground level in winter; spring growth can reach full stature (2–3 m high) by mid-May.

Dense foliage of mature monocultures creates deep shade at grou nd level.

On 28 May 2006, I encountered a territorial male Swainson’s Warbler singing from a

riparian stand of Knotweed on the flood plain of Thacker Creek (222 m above sea level),

*Department of Vertebrate Zoology, MRC-116, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian

Institution, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012, and Center for Macroecology, Evolution,

and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken

15, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø Denmark; gravesg@si.edu.

Manuscript Editor: Noah Perlut

Notes of the Northeastern Naturalist, Issue 26/1, 2019

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

N10

G.R. Graves

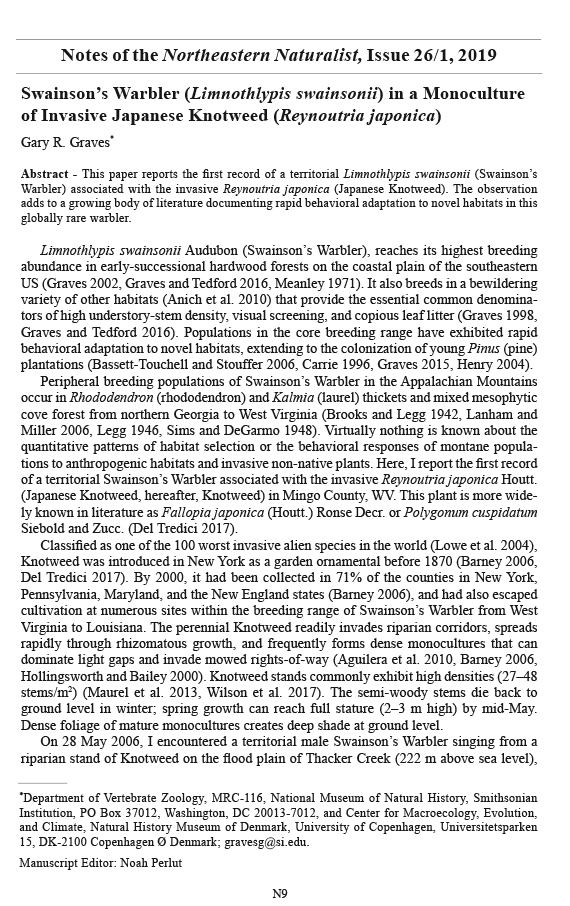

Mingo County, WV (37°35.73'N; 82°7.74'W). The Knotweed monoculture (2–5 m wide)

paralleled the mowed roadside right-of-way for ~50 m and penetrated the understory of the

adjacent second-growth deciduous forest (Fig. 1). The male foraged on the ground and sang

periodically in the dense shade of the Knotweed stand during the observation period (35

min). I recorded a series of songs (GRG 593) and then conducted playback trials (Graves

1996) to test the male’s fidelity to the Knotweed stand. The playback recording consisted

of a mixture of songs and chip notes from several males. The territorial male followed

the playback (77 dB at 20 m) eastward along the road for ~150 m. It returned quickly to the

center of the Knotweed stand when the playback ceased and resumed singing. This behavior

is typical of males on breeding territories (Graves 2001, 2002; Graves and Tedford 2016).

The territory was on private property; thus, I did not quantify stem density in the Knotweed

stand or determine the off-road boundaries of the breeding territory with playback trial s.

The Knotweed stand appeared to provide the essential elements found on all Swainson’s

Warbler breeding territories—visual screening and shade at ground level, high understory-

stem density, and leaf litter (Graves 1998, 2001, 2002; Graves and Tedford 2016).

Intermixed vines, shrubs, and tree saplings at the margins of the Knotweed monoculture

provided abundant potential nesting sites.

The seemingly inexorable spread of Knotweed into the southeastern US will likely

result in fundamental changes in both species diversity and physiognomy of local plant

communities (Wilson et al. 2017) and concomitant changes in avian breeding communities.

The sole paper published thus far on the effects of Knotweed on bird populations in North

America found that the breeding abundance of 3 species in Pennsylvania was positively

correlated with the percent coverage of Knotweed along census transects, while a fourth

species showed a negative correlation (Serniak et al. 2017). This study, however, did not

describe how affected species used Knotweed stands as habitat or as a foraging resource.

The case reported here suggests that invasive Asian knotweeds (Reynoutria spp.) may provide

suitable breeding habitat for the globally rare Swainson’ s Warbler.

Acknowledgments. I thank 2 anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript

and the Alexander Wetmore Fund (Smithsonian Institution) and the Smoketree

Trust for support.

Figure 1. Two views of a stand of Japanese Knotweed occupied by a territorial male Swainson’s Warbler

in Mingo County, WV.

N11

2019 Northeastern Naturalist Notes Vol. 26, No. 1

G.R. Graves

Literature Cited

Aguilera, A.G., P. Alpert, J.S. Dukes, and R. Harrington. 2010. Impacts of the invasive plant Fallopia

japonica (Houtt.) on plant communities and ecosystem processes. Biological Invasions

12:1243–1252.

Anich, N.M., T.J. Benson, J.D. Brown, C. Roa, J.C. Bednarz, R.E. Brown, and J.G. Dickson. 2010.

Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii), version 2.0. Number 126, In A.F. Poole (Ed.). The

Birds of North America (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. Available online at https://doi.

org/10.2173/bna.126. Accessed 18 July 2018.

Barney, J.N. 2006. North American history of two invasive plant species: Phytogeographic distribution,

dispersal vectors, and multiple introductions. Biological Invasions 8:703–717.

Bassett–Touchell, C.A., and P.C. Stouffer. 2006. Habitat selection by Swainson’s Warblers breeding

in Loblolly Pine plantations in southeastern Louisiana. Journal of Wildlife Management

70:1113–1119.

Brooks, M., and W.C. Legg. 1942. Swainson’s Warbler in Nicholas County, West Virginia. Auk

59:76–86.

Carrie, N.R. 1996. Swainson’s Warblers nesting in early seral pine forests in East Texas. Wilson Bulletin

108:802–804.

Del Tredici, P. 2017. The introduction of Japanese Knotweed, Reynoutria japonica, into North

America. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 144:406–416.

Graves, G.R. 1996. Censusing wintering populations of Swainson’s Warbler: Surveys in the Blue

Mountains of Jamaica. Wilson Bulletin 108:94–103.

Graves, G.R. 1998. Stereotyped foraging behavior of the Swainson’s Warbler. Journal of Field Ornithology

69:121–127.

Graves, G.R. 2001. Factors governing the distribution of Swainson’s Warbler along a hydrological

gradient in Great Dismal Swamp. Auk 118:650–664.

Graves, G.R. 2002. Habitat characteristics in the core breeding range of the Swainson’s Warbler.

Wilson Bulletin 114:210–220.

Graves, G.R. 2015. Recent large-scale colonisation of southern pine plantations by Swainson’s Warbler

Limnothlypis swainsonii. Bird Conservation International 2015:1–14.

Graves, G.R, and B.L. Tedford. 2016. Common denominators of Swainson’s Warbler habitat in bottomland

hardwood forest in the White River watershed in southeastern Arkansas. Southeastern

Naturalist 15:315–330.

Henry, D.R. 2004. Reproductive success and habitat selection of Swainson’s Warblers in managed

pine versus bottomland hardwood forests. Ph.D. Dissertation. Tulane University, New Orleans,

LA. 139 pp.

Hollingsworth, M.L., and J.P. Bailey. 2000. Evidence for massive clonal growth in the invasive weed

Fallopia japonica (Japanese Knotweed). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 133:463–472.

Lanham, J.D., and S.M. Miller. 2006. Monotypic nest-site selection by Swainson’s Warbler in the

mountains of South Carolina. Southeastern Naturalist 5:289–294.

Legg, W.C. 1946. Swainson’s Warblers’ nests in Nicholas County. Redstart 13:24–25.

Lowe, S., M. Browne, S. Boudjelas, and M. De Poorter. 2004. 100 of the world’s worst invasive alien

species: A selection from the global invasive species database. The Invasive Species Specialist

Group (ISSG), World Conservation Union (IUCN). 12 pp. Available online at http://www.issg.org/

pdf/publications/worst_100/english_100_worst.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018.

Maurel, N., M. Fujiyoshi, A. Muratet, E. Porcher, E. Motard, O. Gargominy, and N. Machon. 2013.

Biogeographic comparisons of herbivore attack, growth, and impact of Japanese Knotweed between

Japan and France. Journal of Ecology 101:1 18–127.

Meanley, B. 1971. Natural history of the Swainson’s Warbler. North America Fauna 69:1–90.

Serniak, L.T., C.E. Corbin, A.L. Pitt, and S.T. Rier. 2017. Effects of Japanese Knotweed on avian

diversity and function in riparian habitats. Journal of Ornitho logy 158:311–321.

Sims, E., and W.R. DeGarmo. 1948. A study of Swainson’s Warbler in West Virginia. Redstart 16:1–8.

Wilson, M.J., A.E. Freundlich, and C.T. Martine. 2017. Understory dominance and the new climax:

Impacts of Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica) invasion on native plant diversity and recruitment

in a riparian woodland. Biodiversity Data Journal:e20577.